On Friday, April 18, an avalanche occurred off the West Shoulder of Mount Everest, knocking at least 25 people down as it swept through an area between the infamous Khumbu Icefall and Camp I, at an altitude of about 19,500 feet. It was the single most devastating Everest accident ever, killing 16 climbers and making April 18, 2014 the deadliest day in the mountain’s history.

In one fell swoop, the tragedy also marked the entire 2014 climbing season on Everest as the deadliest ever, since the mountain’s annual death toll has, until now, never exceeded 15. It was big news when 10 people died on the mountain, in various incidents and of various causes, in 2012, and the deadliest year before that was 1996, when 8 people died near the summit during a storm in May and 7 more were killed at other times. Into Thin Air, Jon Krakauer’s retelling of that storm in 1996, has long informed popular conceptions of mountaineering disasters. But what happened last week was quite different.

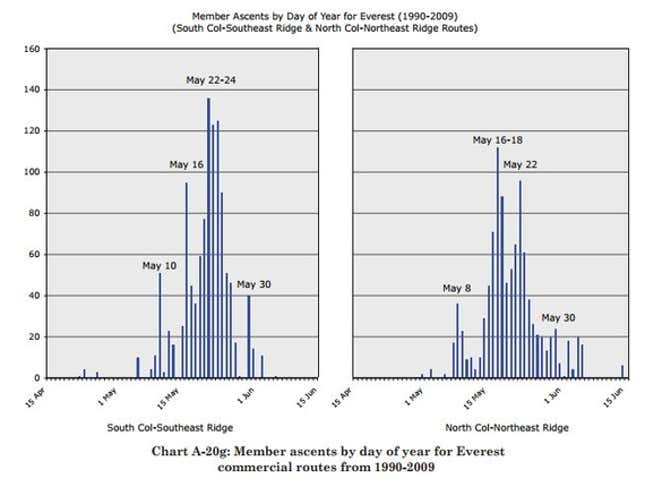

The avalanche victims were not on their way to the summit; at this point in the spring, hardly anyone is venturing higher than Camp II, or 21,000 feet, on the 29,000-foot peak. Most climbers will head for the summit in mid-May.

The 2014 climbing season, in fact, has only just begun. And while you might expect the push for the summit to be the most dangerous part of an Everest expedition, that’s not necessarily the case. The most dangerous steps on Everest are taken between 18,000 and 21,000 feet, and they’re steps that many Western climbers are actually able to avoid—thanks to the Nepalese Sherpas they hire to help install fixed ropes, carry gear, and break tracks on the route to the top. Those who perished in last week’s avalanche were all at work ferrying loads of gear between Base Camp and Camp II. They were all Sherpas.

It’s a stark reminder that there are two classes of Himalayan mountaineers—those who pay to climb, and those who get paid to support them. The people spending money, to the tune of tens of thousands of dollars each, are foreign adventure enthusiasts. The people earning money, typically several thousand dollars each (or more for head Sherpas), are natives of Nepal for whom Everest expeditions provide lucrative livelihoods to support extended families.

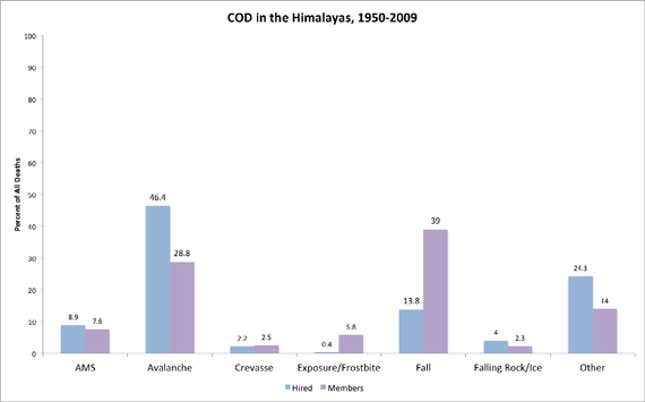

Throughout the Himalayas, avalanches are the leading cause of death for Sherpas. The chart below, assembled from numbers collected by the Himalayan Database, shows that both Sherpas (“hired”) and their customers/bosses (expedition “members”—a telling word choice, implying that Sherpas, though essential embeds in climbing groups, are set apart from the rest of the team) are more likely to die from falls or avalanches than other circumstances.

The Himalayan Database counts 608 “member” deaths and 224 “hired” deaths on mountains in Nepal, including Everest, between 1950 and 2009. Almost 50% of hired deaths were due to avalanches, while nearly 40%of member deaths were attributed to falls.

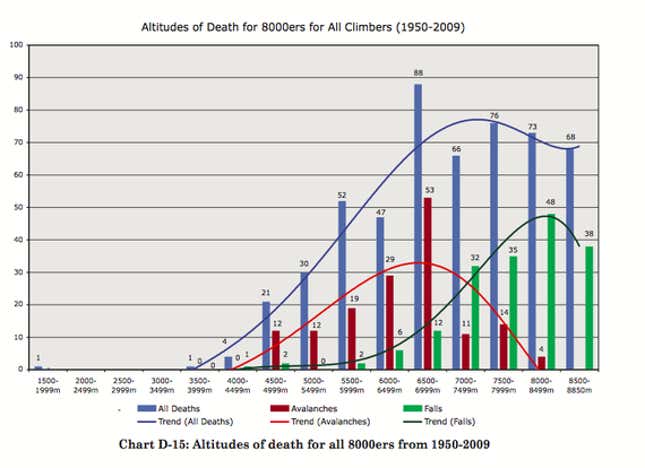

These patterns have a lot to do with who does what, and where, on mountains like Everest. Sherpas spend much of their time establishing and supplying camps in avalanche-prone zones. Paying expedition members move through those zones as quickly and efficiently as possible to save their energy for summit bids, where the risk of avalanches is lower but the air is thin and falls are more likely to occur. The graph below, again from the Himalayan Database researchers, shows deaths by altitude.

The data speaks to the most illuminating lesson of the recent tragedy on Everest—how the (growing) divide between Sherpas and the Western climbers they work for affects each group’s mortality on the mountain.

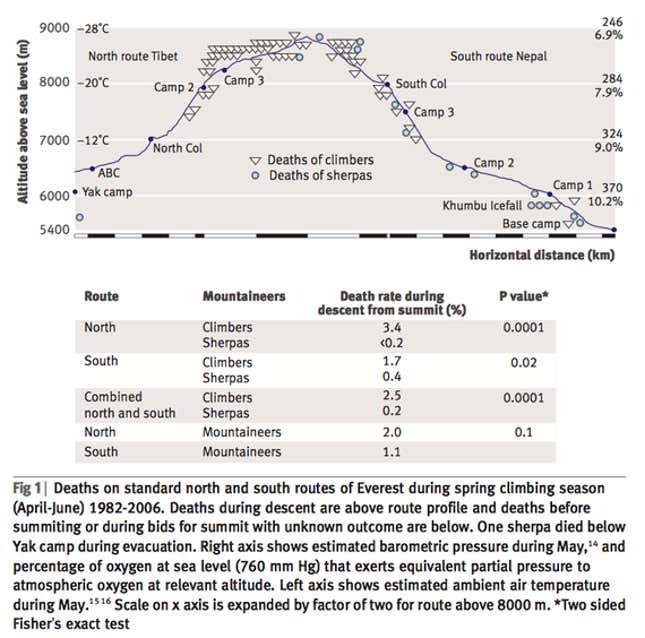

In 2008, a study in the British Medical Journal examined this dynamic, tracking Everest death patterns between 1921 and 2006. The chart below is based on deaths between April and June from 1982 to 2006.

Most commercial expeditions approach Everest’s summit from the Nepalese side, relying heavily on Sherpas to set up camps and transport gear below the South Col. The summit has become the most dangerous place for expedition members—notice how many of them are killed on their way down from the summit to the South Col, and how great the risk of falling is up there. But, arguably, these patterns exist because expeditions members are largely shielded from the mountain’s other dangers—the Khumbu Icefall before ”Ice Doctors” (Sherpas) have established safe routes through it with ladders and ropes; the exhaustion of carrying equipment between Base Camp, the Icefall, and higher camps; the repeated, precarious steps over crevasses and under ice shelves during multiple gear shuttles between camps. The Sherpas bear the brunt of these risks.

“My passion created an industry that fosters people dying. It supports humans as disposable, as usable, and that is the hardest thing to come to terms with.”

There has always been a divide between Sherpas and Western summit-seekers, but these tensions have increased in recent years as Everest has become more accessible to unskilled-but-well-heeled climbers. The world’s tallest mountain has become much safer for the average Joe than ever before. For the people who live in its shadow, though, and must return to it again and again to earn a living, the risks haven’t declined in the same way.

What are the ethical implications of this divide? Grayson Schaffer at Outside magazine explored this question a year ago in “The Disposable Man,” an in-depth look at Sherpa deaths on Everest. On Friday, in a post for Outside, he revisited that question and concluded that the climbing business today “clearly values life on a two-tiered basis: Westerners at the top; Sherpas on the bottom.” He continued:

If, say, 1% of American college-aged raft guides or ski instructors were dying on the job—the mortality rate of Everest Sherpas—the guiding industry would vanish. But Himalayan climbing is understood to be extremely dangerous, and people who play the game still cling to its romantic roots in exploration rather than its current status as recreational tourism.

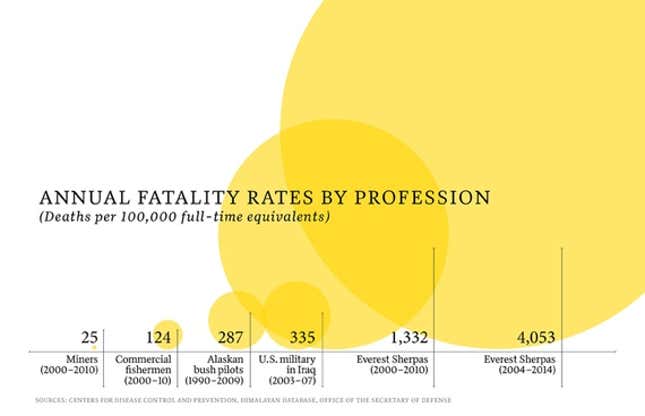

Outside also crunched numbers from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Himalayan Database to generate a comparison of fatality rates for Sherpas and other people who work in harsh environments. Being a Sherpa on Everest these days is far more dangerous than, say, being a soldier in Iraq from 2003 to 2007.

Western expedition leaders are acutely aware of this sobering reality, and many have established funds for the families of fallen Sherpas. It’s difficult, though, to assuage the guilt of leaving the mountain with fewer people than you brought there. Melissa Arnot, the Eddie Bauer-sponsored American mountaineer who has summitted Everest five times, had a Sherpa die on an expedition of hers in 2010. Reflecting on this in 2013, she told Schaffer: “My passion created an industry that fosters people dying. It supports humans as disposable, as usable, and that is the hardest thing to come to terms with.”

This post originally appeared at The Atlantic. More from our sister site:

The baby blues can happen to any parent

How America lost Vladimir Putin

Why corporations fail to do the right thing