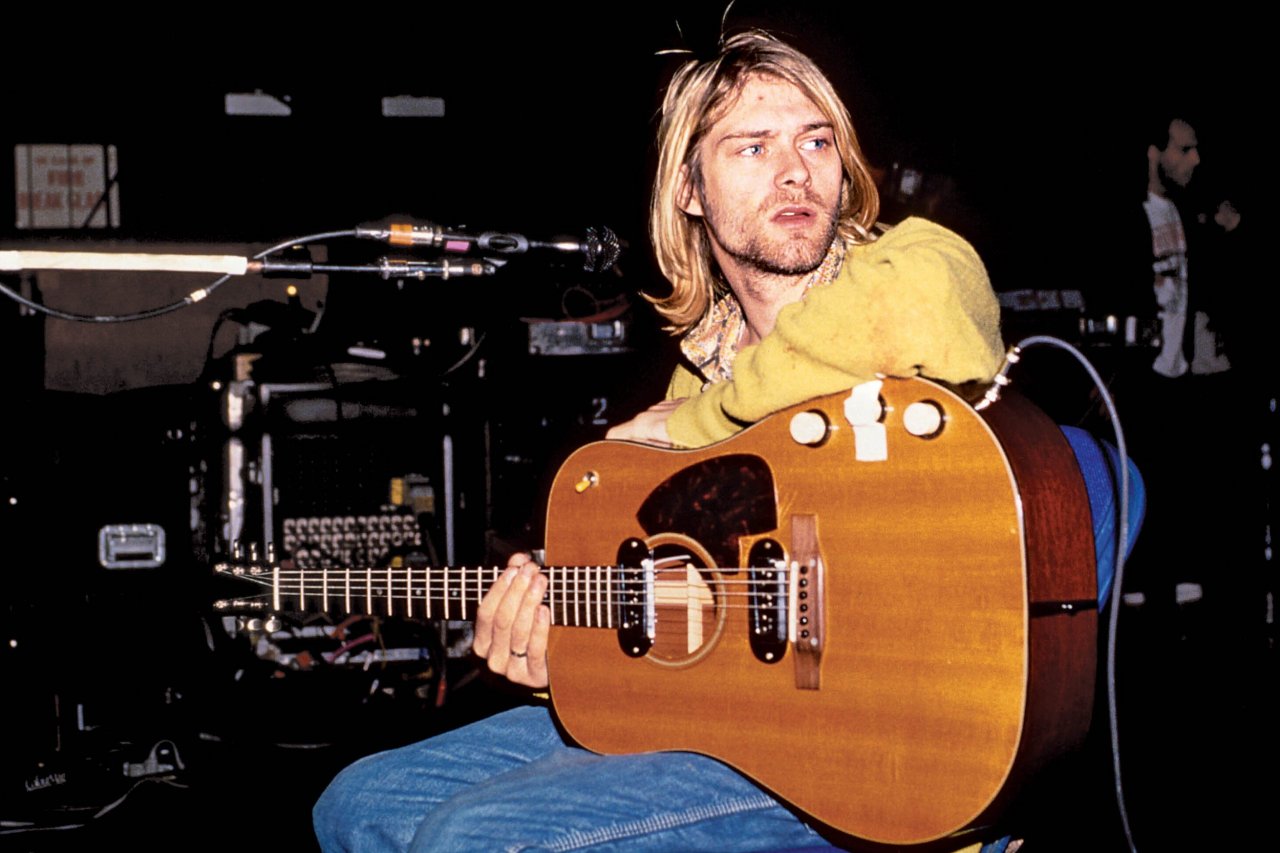

Here is a challenge: Find a rock and roll legend with more mythos surrounding him than Kurt Cobain. The bedraggled Nirvana frontman seethed through the late '80s and early '90s, inspiring a generation of plaid-clad youths reeking of Teen Spirit and apathy to wake up and wield guitars like weapons. Cobain became the sheepish poster boy for a generation he felt isolated from, going from logging-town loner to rock star faster than you can say "Lithium."

Of course, the most infamous part of Cobain's legacy came after his redemptive rise. Twenty-one years after Cobain's April 5, 1994, suicide by shotgun, his life continues to be commemorated with candlelit vigils and scrutinized by Courtney Love–crucifiers. The Myth of Cobain has been immortalized in genre-spanning songs and ill-fated documentary films, notably English documentarian Nick Broomfield's 1998 attempt, Kurt & Courtney. In it, Broomfield goes down a badly edited rabbit hole through post-Cobain Seattle, all the while plucking on the cringeworthy conspiracy theories surrounding the musician's death. It also has the distinct honor of being one of the only films to ever be thrown out of the Sundance Film Festival (in 1998, for violating music rights).

But this year's Sundance saw standing ovations, tears and acclaim during the premiere of a very different film about the fallen rock icon, Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck. Directed by Brett Morgen and executive produced by Cobain's daughter, 22-year-old Frances Bean Cobain, the film is a loud, brutal glimpse into a life that continues to loom titan-size.

As far as Cobain closure goes, this film "may be the final chapter," Morgen told Newsweek. A key failure of previous Cobain documentaries was lack of access to Nirvana's songs and illuminating archival footage. With zero exclusive material, previous attempts have essentially been chasing a shadow. Montage of Heck—which has its HBO premiere May 4—is instead the damn-near-closest thing we have to physically resurrecting the guy, thanks to Morgen's "six years of legal wrangling and two years of filmmaking." Devoid of speculative myth-building, the film instead provides a dizzying dive into the growling musician's mind in his own words.

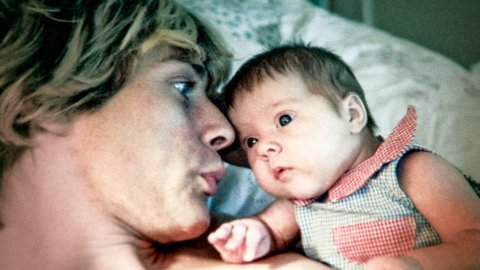

Before he could realize his vision, Morgen had to contend with the same obstacles other Cobain documentarians faced, such as people hesitant to open up about the musician, even though they held the keys to his story—and to the storage locker where the notorious pack rat's belongings were rotting. Though Frances Bean, who was only 20 months old when her father committed suicide, has held the rights to his likeness and name since 2010, it was her mother, Courtney Love, Cobain's widow, who was the catalyst for the burgeoning Montage of Heck project. She'd met with Morgen in 2007, after seeing his documentary The Kid Stays in the Picture—an adaptation of a book depicting the rollercoaster life of film producer Robert Evans—and becoming a fan. She asked if he might be keen to make a documentary about her late husband because "it was time to examine this person and humanize him and de-canonize these values that he allegedly stood for—the lack of ambition and these ridiculous myths that had been built up around him," she recently told The New York Times.

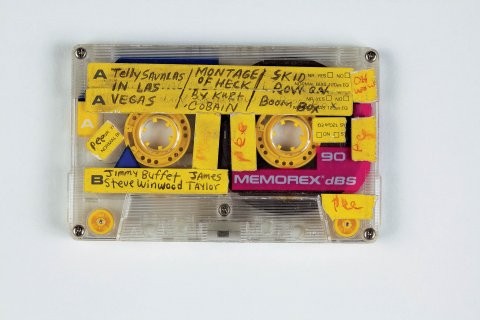

Morgen agreed, so Love led him to the California storage unit where the remnants of Cobain's life were stored. There, Morgen found heart-shaped boxes, guitar cases filled with art supplies and sputtering "sound collage" mixtapes Cobain had created, including a 1988 cassette titled "Montage of Heck." As the filmmaker dug through the archives, he found that Cobain's tale was much more straightforward than anyone had previously thought. He wasn't just a miserable junkie or someone who took his life because he couldn't deal with fame. Instead, a picture began to form of a man who, in very human ways, felt isolated from his peers and longed for a meaningful connection with those closest to him. Cobain was also a formidable painter, illustrator, cartoonist and budding sound engineer with an itch to create, keeping a kind of visual autobiography since the tender age of 3. "He never had idle hands," Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic recalls in the film.

While in the storage unit, Morgen discovered something that would help make this case: personal recordings of the frontman narrating his own life, including formative moments, such as his first suicide attempt at 14. "People talking about his life is nowhere near as interesting as how he depicts his life," Morgen says. For the final film, animator Stefan Nadelman added hyper-realistic renderings of Cobain's spoken accounts, which are woven through the narrative alongside concert footage, interviews and sketches from his many notebooks. "He left all of this art that provides a beautiful reflection of what he was feeling," says Morgen. "Kurt is gone, but his art remains, and it's vibrant, and it's moving. It needed to come out and tell the story."

Bolstering Cobain's own words are testimonials from some of the people closest to Cobain, including his mother, sister and first girlfriend, Tracy Marander. "That's a difficult group to bridge, but Frances was the glue," Morgen says, noting that Marander was especially cagey at first. In a stroke of visual genius, Morgen made sure that the most challenging questions were intentionally asked in the testimonials as the sun was waning, and shadows fell across the interviewees' faces. Dripping footage of intestines emphasizing Cobain's well-documented stomach pains—which he self-medicated with heroin—add a grotesquely visceral quality to the portrayal of his struggles.

Cobain fanatics will likely note that only one close friend, Krist Novoselic, was interviewed for Montage of Heck. Former Nirvana drummer Dave Grohl, whom Morgen says he chatted with, is noticeably absent. (Scheduling conflicts prevented the Foo Fighters frontman from making the film's final cut.) Missing too is Bikini Kill's Kathleen Hanna, the friend who infamously scrawled "Kurt Smells Like Teen Spirit" onto a wall, and her bandmate, Tobi Vail, who briefly dated Cobain. (For Cobain memories from former riot grrls and grunge bands, Mark Yarm's grunge oral history, Everybody Loves Our Town, should fill in the gaps left by the film.)

Cobain's friendships and place in the Pacific Northwest grunge scene are less of the film's focus than is his lifelong inability to really belong anywhere. Montage of Heck takes viewers through the frontman's continual struggles to create stability: first as he's shuffled around different homes as a child, then as he tries to build a home with Marander in Olympia, Washington, then with his bandmates in Nirvana and finally with Love and Frances Bean.

The film also attempts to debunk the idea of Cobain's martyrdom, that he somehow died for your sins. There are many reasons Cobain ended his life and many questions that will likely remain unanswered. The film is able, however, to shed light on certain recurring themes of discontent, humiliation and betrayal as it moves from his unstable childhood to his withdrawn adulthood.

Four days after Cobain's suicide, Love's band Hole released the album Live Through This. In it, she would famously declare that she wanted to be the girl with the most cake. Cobain instead "wanted to be the most loved," as his stepmother, Jenny Cobain, explains on-screen.

Frances Bean got involved in Montage of Heck partially because she has "no memory of Kurt," as she recently told Rolling Stone's David Fricke. "I'm the only person on earth who is emotionally invested in the film but can watch it like an audience member." Because of this, she was able to make critical decisions with Morgen, who says the 18-hour days and time away from his children were worth it, if just to give Cobain's daughter two hours with the father she never knew. "When she saw it, she said: 'You made the movie that was in my head and gave me time with my father," Morgen says. "And that was...powerful. That was the deepest thing I've ever done as a filmmaker."