Robert Bigelow spent decades amassing the fortune he needed to start his own space company, a dream he had since he was a boy growing up in Las Vegas in the 1950s. At the turn of the millennium, with cash from his real estate empire and hotel chain, he went shopping for the technology he needed to expand off-planet.

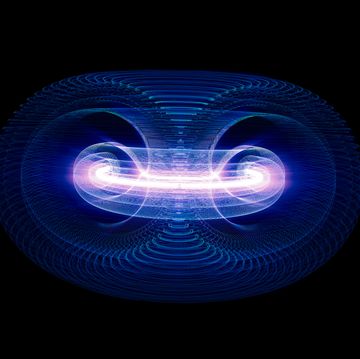

He cast his eye on a cancelled NASA program for expandable space habitats called TransHab. The idea was to launch a compactly folded structure made of high strength but flexible materials such as Kevlar. Once it was in space, the structure would expand to full volume using air from the life-support system, providing more living space than any preassembled room you could launch. NASA cancelled the program after building prototypes, but those units proved the concept worked.

That's when Bigelow swooped in, licensed the tech, and hired the NASA engineers. Thirteen years later he's selling parts of NASA's technology back to them, signing a contract for a closet-size addition to the International Space Station.

When PM reached Bigelow, he described the project as a "three-year overnight success." That's how long it took for the deal to come together, with the clincher being a transportation system to get the inflatable room up to the ISS now that the space shuttles are retired.

"We're demonstrating progress on a technology that will advance important long-duration human spaceflight goals," NASA deputy administrator Lori Garver said in a January 16 statement announcing the contract.

Bigelow's room will fly on the eighth cargo mission of the SpaceX Dragon, currently scheduled for 2015. First, Dragon will hook onto the station. The ISS robotic arm will then extract the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module, or BEAM, and attach it to the station's Tranquility node. Once in place, the BEAM will expand to its full 52-cubic-foot volume with the help of compressed nitrogen and oxygen released from onboard tanks.

"I would imagine the astronauts on board are going to use it for storage purposes," Bigelow says. "It might be a place for them to get away and get some sleep without being bothered. They say always that it's kind of hard to find places to call your own for sleeping quarters on the ISS." The plan is for the BEAM to remain on-station for two years, but Bigelow anticipates that its stay might be extended.

Bigelow all along has been planning to launch its own station, called Space Station Alpha, into orbit by 2016. Alpha would be composed of two of Bigelow's planned BA-330 modules, each of which has a volume of 330 cubic meters, or 1082 cubic feet. The BEAM module going to the ISS will be much smaller, about the size of the two unmanned Genesis test modules BA launched in 2006 and 2007. But it will give NASA a chance to test an expandable habitat in space. NASA will check for leaks over the course of the BEAM's mission and compare its ability to shield astronauts from cosmic radiation to that of the conventional aluminum segments of the station. For Bigelow, that would be a proof of concept that could show future customers it can deliver the goods.

Bigelow says his company has just completed a 50-page leasing agreement for its future customers. He declined to show it to PM, citing proprietary terms that he did not want to be made public. The basic terms of the agreement are clear enough, however. Bigelow intends to put up expandable habitats in orbit as the first commercial space stations, and lease them to out to corporations, governments, wealthy individuals, or anyone else who wanted a place to stay in space.

For a fixed price of $26.25 million per person including transportation, a space traveler could stay in orbit aboard the habitat from 10 days to a couple of months, Bigelow says. "We might be able to fly them longer than that, for maybe up to four months if they wanted," all for the one price. For a price comparison, after the shuttle retired, NASA hired the Russian Federal Space Agency to send its astronauts to the ISS for $62.7 million a seat.

The price of "$26 million and change," as Bigelow puts it, assumes transportation aboard the planned manned version of the SpaceX Dragon spacecraft, which is currently in development. A flight aboard the planned CST-100 spacecraft, now in development by Boeing and BA, would cost more (about $36.75 million) because it would use an Atlas 5 rocket, more expensive compared with SpaceX's Falcon 9.

Bigelow says his NASA contract is the first step along a path he hopes will take his company beyond low Earth orbit. "We want to provide NASA with a cost benefit on other locations using full-scale [habitats] that they're not going to get anywhere else," Bigelow says. He wouldn't say more, except that BA and NASA have been talking at length about future possibilities. "These discussions have been ongoing for about a year, and we're getting into quite specific details now."

For now, he's excited just to see the inflatable structures get off the ground. For the past several years Bigelow has been waiting for the commercial space industry to take off and provide a way to get his modules off the planets. During the recession, with no way to launch any modules, Bigelow has reduced his workforce.

Now, he says, "we are staffing ourselves back up." BEAM is already under construction on the BA factory floor. At last, Bigelow's space dream may be about to blow up.

Michael Belfiore's book Rocketeers: How a Visionary Band of Business Leaders, Engineers, and Pilots Is Boldly Privatizing Space, details the startup of Bigelow Aerospace.