Until nine years ago, when he began shooting beavers with a .22 caliber rifle, Miguel Gallardo had never owned a gun, let alone killed an animal. He had spent a decade working to protect Chile’s flora and fauna, patrolling the country’s wilderness as a forest service official. Then Gallardo was dispatched to Puerto Williams, a small wind-beaten town on Navarino Island, near Chile’s southernmost tip.

While exploring his new territory in 2010, Gallardo was stunned. Where there had once been a lush forest of lenga beech trees, he found fallen trunks, naked branches, and gnarled stumps. “Everything was white because it was dead. It looked like a ghost forest,” he recalls.

The culprit was a colony of voracious beavers, which had felled the trees to feast on their leaves and construct dams from their branches. The structures had rerouted rivers and caused massive flooding that made it difficult to walk.

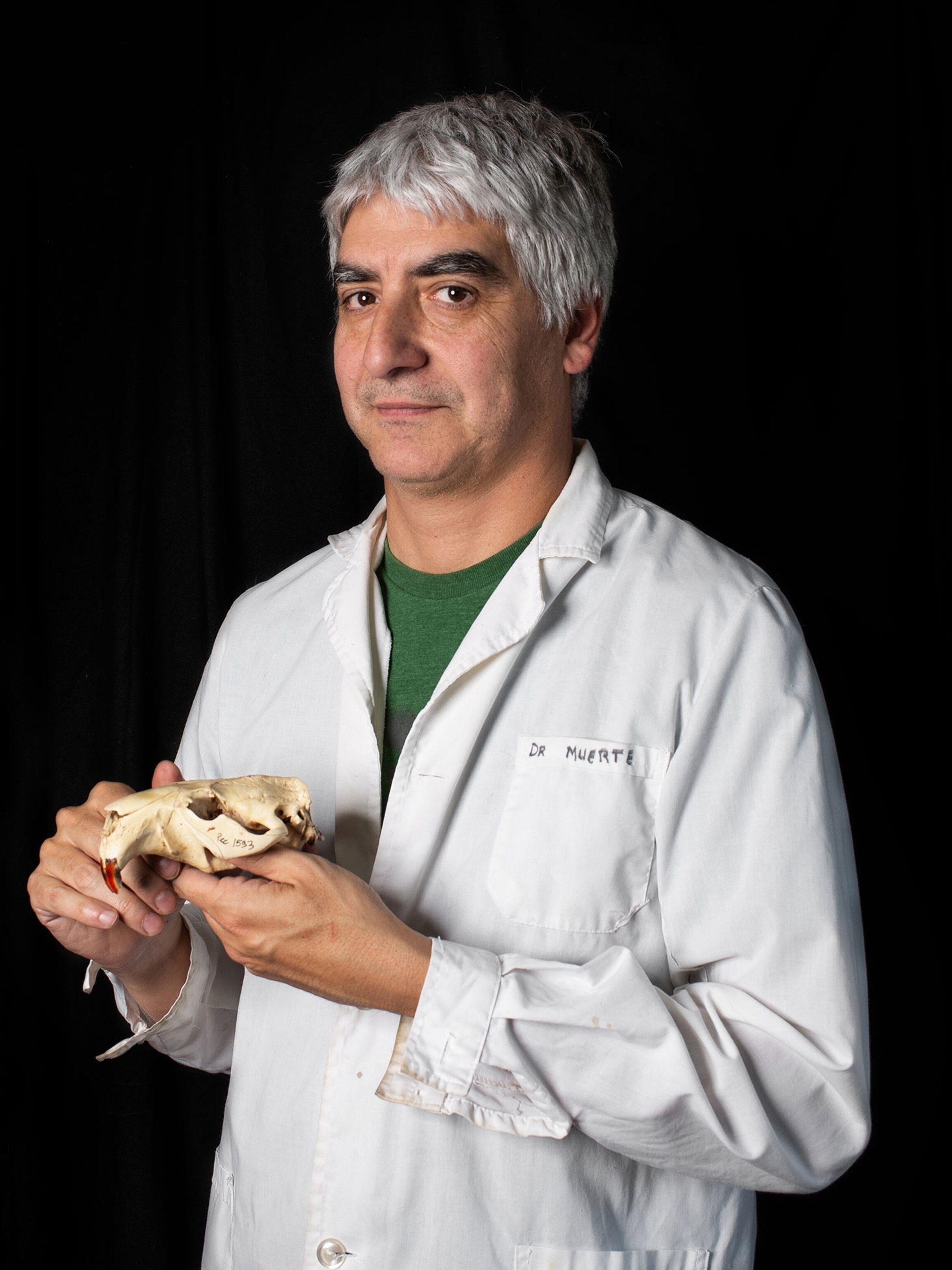

Moved to do something, Gallardo registered for a permit, bought a gun, and began hunting as many beavers as he could. In 2015, Gallardo quit his job with the forest service and launched Navarino Beaver, a tourism company that allows visitors to trek through the phantom forests, hunt beavers, and taste their lean meat, which Gallardo prepares “al disco”—basically stir-fried on a round pan over a flame.

Such a career pivot might seem surprising. But like many other concerned conservationists in South America, Gallardo had come to believe that the survival of Patagonia’s forests hinged on the beaver’s demise.

Canadian beavers in South America

Beavers were supposed to “enrich” Patagonia, economically and ecologically. At least that was the ambition of Argentina’s military when it flew 10 pairs of Canadian beavers from Manitoba to Tierra Del Fuego, Argentina’s southernmost province, in 1946. The soldiers set the beavers loose on the shores of Lake Fagnano in hopes of spurring a fur trade and attracting more residents to the sparsely populated area.

A video clip from “Sucesos Argentinos” (Argentine Successes), a television series that aired from 1938 to 1972, expressed concern about the fragility of the experiment. Beavers are monogamous; if one of the animals were to die, the program’s announcer fretted, its mate would be unlikely to reproduce.

But such worry was misplaced. While the fur trade never materialized, what did explode were beaver numbers.

In contrast to North America, which is home to bears and wolves, the island of Tierra del Fuego has very few natural predators that hanker after beaver meat. With access to extensive forests and steppes they could colonize without fear, the beavers rapidly dispersed and multiplied.

In the 1960s, beavers crossed to the Chilean side of Tierra del Fuego. “They don’t recognize borders. In fact, they eat the border fence,” quips Felipe Guerra Díaz, the Chilean national coordinator for the beaver project of the Global Environment Facility (GEF), an international partnership that funds environmental efforts. By the early 1990s, residents began spotting beavers in the Brunswick Peninsula on the Chilean mainland, meaning the creatures had braved the unpredictable currents of the Strait of Magellan.

In their wake they left phantom forests. North American trees have evolved over millions of years to survive beavers’ industrious chewing, explains Ben Goldfarb, an environmental journalist and author of Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter. “Trees like willow, cottonwood, American beech, and alder have all evolved responses to beaver chewing and flooding. They re-sprout when you cut them down, produce defensive chemicals, and tolerate wet soils.” But because beavers are not native to South America, the continent’s trees have not developed the same defenses.

The governments of Argentina and Chile began to realize the scale of their beaver problem in the 1990s. Around that time the countries tried to encourage recreational and commercial beaver hunting, but low fur prices stymied the effort. A 1998 article in La Nacion, an Argentine newspaper, quotes beaver hunter Juan Harrington as saying: “They are very beautiful but very destructive animals. And the only way to control them is to hunt them. But since their pelts are not worth much, $20 at most, no one is very motivated.”

Left largely unchecked since then, GEF estimates the beaver population has grown to between 70,000 and 110,000 in Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. The beavers have colonized at least 27,027 square miles of territory and decimated nearly 120 square miles (31,000 hectares) of peat bogs, forests and grasslands—an area almost twice the size of Washington, D.C. A 2009 scientific paper calls beavers’ impact in Patagonia “the largest landscape-level alteration in subantarctic forests since the last ice age.”

When they studied Navarino Island, researchers at the University of North Texas found that beaver-modified habitats supported two other invasive species: muskrats and mink. The muskrats gravitate towards stagnant ponds created by beaver dams; they are in turn hunted by mink, a species that also preys on native geese, ducks, and small rodents. The researchers hypothesized that an “invasive meltdown process,” in which the negative impact caused by an invasive species is exacerbated by another invasive species, might be at play.

Beavers have damaged infrastructure, too, flooding highways and culverts, and damaging farmland. They often chew through fences meant to contain sheep; in 2017, beavers gnawed through fiberoptic cables in Tierra del Fuego, knocking out internet and cell service in its biggest city. Guerra Díaz says a recent study shared with GEF suggests damage caused by beavers costs Argentina alone $66 million a year. (Related: Beavers are back in Britain—and they’re a nuisance.)

Eradication

Since 2008, Argentina and Chile have agreed that controlling the beaver population would not be enough: They would need to pursue total eradication. A report released that year with input from researchers based in New Zealand and America suggested eradication was feasible, but it would cost up to $33 million. After securing grants from GEF and other partners, in 2016 the countries began a series of pilot projects to explore the best way to proceed.

Earlier this year, researchers released the preliminary results from their pilot project in Argentina’s Esmeralda-Lasifashaj region, which ran from October 2016 to January 2017. During that period, 10 trappers, which the report calls “restorers,” lay body-gripping traps and snares around the designated area, which is popular among cross-country skiers. Overall, they caught 197 beavers in traps and shot an additional seven beavers. The trappers believed they had completely rid the area of the animals, only to later spot several on motion-triggered cameras. It was unclear whether the errant beavers were “re-invaders” that had trudged in from outside the pilot area or if they had survived the trappers’ initial attempts at capture.

For Erio Curto, the director of Fauna and Biodiversity for Tierra del Fuego’s environment ministry, who helped conduct the study, the results reaffirmed that eradication is technically possible. But that doesn’t mean it will be easy.

Tierra del Fuego is made up of hundreds of small, rugged islands that are difficult to reach. If beavers survive on even one, Curto warns, they could repopulate the entire archipelago and even spread back to the mainland. After the pilot studies are completed in the next few years, the governments of Chile and Argentina will need to agree on how to proceed; pursuing different strategies in each country would result in certain failure. Curto explains: “Achieving eradication will depend exclusively on sustained political will.” In Argentina, where high inflation has pushed a third of the population into poverty, it might be particularly difficult to convince people to care about gnawed forests in the far south.

But if they traveled to see the devastation beavers cause with their own eyes, Gallardo believes Argentines and Chileans alike would support their eradication. Recently, he had a customer who introduced himself as a veterinarian who didn’t eat meat and abhorred the idea of killing animals. By the end of their day together, trekking through Navarino Island’s skeletal forests, the veterinarian had eagerly helped Gallardo shoot five beavers. “He finally got why I hunt,” Gallardo says. “It’s not to kill animals. It’s to save the ecosystem. It’s not the beavers’ fault—cutting down trees is in their nature. The blame rests with humans.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

- Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?

- This year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning signThis year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning sign

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

- See how ancient Indigenous artists left their markSee how ancient Indigenous artists left their mark

Science

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

- Every 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost timeEvery 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost time

- How do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tipsHow do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tips

- Why outdoor adventure is important for women as they ageWhy outdoor adventure is important for women as they age

Travel

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads

- Slow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capitalSlow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capital