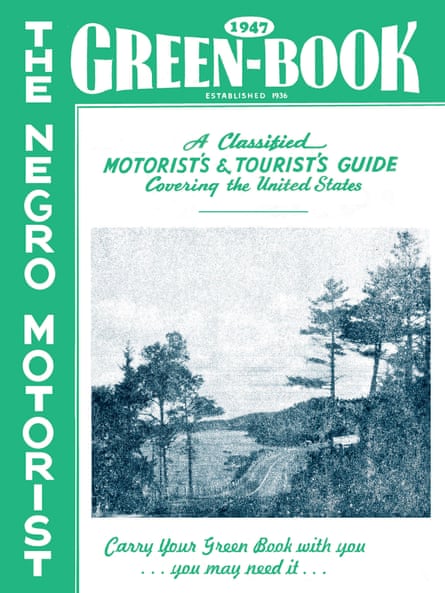

A series of travel books written for African Americans travelling in the segregated US of the last century, which listed the places in which they were allowed to stay, shop and eat, is being republished in facsimile editions. Recent sales have topped 10,000 copies.

Harlem postal worker Victor Hugo Green published the first guide, The Negro Motorist Green Book, in 1936. It listed the hotels, shops and restaurants that accepted custom from black people: “Carry your Green Book with you … you may need it.” Further editions would follow through the 1940s, 50s and 60s, until civil rights laws brought an end to legal segregation.

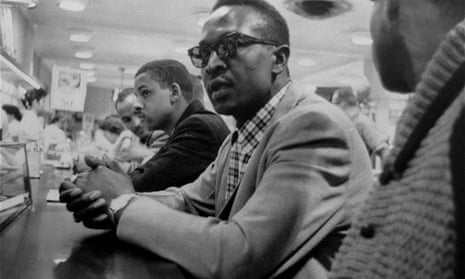

The Green Book became a necessity for the rising African American middle classes, who had the financial means to travel, but were barred from staying in certain hotels or eating in particular restaurants.

Nat Gertler, publisher at About Comics in California, has just republished the 1947 edition of the guide, having previously released facsimiles of the 1940, 1954 and 1963 books. According to Gertler, in just over a year, the Green Book facsimiles have sold 10,000 copies, through online sales and in gift shops in institutions including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, and the National Civil Rights Museum Memphis, Tennessee.

“The reaction to the book is very, very good … and when you can hand one to someone directly, it’s amazing. Unless they’re an older person of colour who lived through the era, they probably heard about this sort of segregation in school – at least, I hope they did – but that was as a very abstract thing. When they get their hands on a Green Book, you can see a dawning cross their face, because it really depicts a practical reality,” said Gertler.

“The heart of the book is a fairly short list of places where black people could have stayed. You look up your home town, and maybe there’s no places listed, or maybe there’s three … and two of them are ‘tourist homes’, basically the Airbnb of the day, private residences that would rent you one of their rooms to crash for the night. There’s this certain expectation that the book might be filled with angry polemics about how unfair this all is, or explaining why this guide was needed, but there’s little of that. The person buying this understood very well what the situation was, they were living it every day. So there were things like Victor Green writing about how he expected that some day this guide would no longer be needed – he didn’t live to see that day, alas – but for the bulk of the book it is just practical information, listings and ads.”

Gertler said he first heard about the Green Books a few years ago. It “piqued my interest particularly because, while I’m not a person of colour myself, my beloved stepmother is half-black, half-Cherokee. And I’d talked with her about what it was like travelling the US under segregation. She’d be on a trip with people from her school, and while all the white girls would stay at a hotel in town, she’d have to find a special place outside the city limits that would take her,” he said.

But he was unable to locate a copy. “You figure, hey, they printed piles of these things, it shouldn’t be too hard – but of course these were disposable, practical items … So copies are rarely available, and when they are, they’re thousands of dollars. These are museum items,” he said.

The Green Book was sold through mail order and in service stations – specifically Esso branches, as a note in About Comics’ edition explains: “Esso not only served African American customers, it was willing to franchise its stations to African Americans, unlike most petroleum companies of the day.”

In a foreword to one edition of his guide, Green wrote: “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment.”

Green died in 1960. The Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion