He Planned a Treasure Hunt for the Ages — Until He Went Missing

Let’s start at journey’s end. Some adventures exact a terrible cost.

It’s the last Sunday in January. More than 300 guests walk single file into the Arcata Community Center in far North California. Some wear blazers with sneakers, and some wear gingham dresses with muddy hiking boots. They patiently wait their turn and then sign their names into the guest book.

More from Rolling Stone

That Time Kacey Musgraves Wowed Nashville -- But Still Didn't Get Played on the Radio

Exclusive: Video Undercuts DaBaby's Self-Defense Claim in 2018 Killing

Bella Poarch Conquered Her Past, the Navy, and TikTok. Now She's Coming for Pop Music.

They are here to celebrate an extraordinary young man. His achievements are perfectly organized and displayed chronologically on a series of tables. There he is as a little boy with his father and grandfather preparing to launch a rocket into the Colorado sky. There are snapshots of a handsome kid with lank hair climbing on rocks, and another where he is playing his guitar. Then a pair of blue canvas shoes with sand still clinging to shredded soles.

You glance up and see someone who resembles the young man. It’s his brother. He’s a different kind of free spirit, with glasses and blond-green hair, his skinny body clad in Doc Martens, a Phish hoodie, and a Bikini Kill T-shirt. He stops for a moment and looks at the different stages of his brother’s travels, and then moves on alone.

The tables continue. The boy grows up and his dreams get more ambitious. There is a ragged copy of The Fellowship of the Ring. Then, a list of astronaut requirements scrawled in a teen’s hand. One of the prerequisites is a private pilot license. Magically, the next table features the young man standing outside a plane. He got his license last fall.

And then a treasure hunt. He was an old hand at them. He grew up solving his dad’s hunts with his brother, both in Colorado and down in the caves and cliffs that dot the far Northern California coast, where they played as boys. But this one is different. The boy’s treasure hunt is more elaborate, and it wants the competitors to step out of their comfort zone. There were riddles, keys, ciphers, and a map that, if plotted correctly, would lead you to the final treasure.

For five days, the young man watched with joy as his friends and family raced all over town, rappelling down cliffs and climbing trees in search of answers. Sometimes, the young man would drop in and film his friends as they searched, his all-encompassing laugh occasionally shaking the video. The treasure was his utopian version of life, adventures and risks that pushed everyone’s limits, including his own.

But that is the last table. There is no photo of the man with the treasure-hunt winner. What comes next is not from an epic quest that ends with the knight winning the hand of the fair maiden. Don’t misunderstand. The maiden is here, but she is sitting in the second row wearing a brave smile as her brother and parents wrap her in a group hug.

The reason for her sadness becomes clear once the visitors step beyond the table. On the floor are smashed pieces of green wood twisted in a way that suggests remnants left over from a home demolition. But they’re not. They are the remains of a canoe.

On Dec. 30, Hunter Nathaniel Lewis paddled a lake canoe into the Pacific Ocean. He was maybe 100 yards from Trinidad Beach, a majestic stretch of coast where he and his brother climbed rocks and chased sea and sand as boys. At night, they huddled with their friends as a bonfire blazed near Grandmother’s Rock, where, legend says, a Tsurai woman eternally waits for the sea to return her grandson.

Hunter was seen pushing off from shore around 11 a.m. It was a typical December day, the temperature in the high 40s, matching the cold of the ocean. Where Hunter was going wasn’t clear to a local fisherman shoving off at about the same time. All he saw was a skinny boy in board shorts and a T-shirt, despite the chill, happily paddling without a care in the world.

“Long ago in your family history lies the fabled pirate legend the Lost Lewis,” Hunter wrote, “who was the last known person to hold the priceless Mayan artifact.”

And then he vanished. Now his smiling face was on a poster next to the word “MISSING.”

Hunter was never found and is presumed dead. He was 21. There will be no more tables with tales of future adventures. Instead, there will be moving boxes holding memories of a life. Right now, there’s just Hunter’s mother sitting on a folding chair and weeping into her hands.

This is the story of how Hunter Lewis became the Lost Lewis treasure.

Last Christmas morning, Hunter Lewis sat on his dad’s couch in Blue Lake, California. He wore a T-shirt and pajamas and patiently waited as his two stepsisters opened their presents. He held hands with his girlfriend, Kinsley, an effervescent redhead he hoped to marry after they graduated from college in another year. Someday, Hunter promised, they would have redheaded kids that they would raise on Mars. He was certain he was going to be an astronaut. He watched the kids rip open gifts, and then would lean over and give Kinsley a passionate kiss that didn’t surprise his family, since they had warned everyone that they were strong advocates of PDA.

Hunter handed everyone personalized envelopes once the presents were done. Simultaneously, he emailed the same letter to his mother, Micki, and brother, Bodie, a few miles away, as well as to a dozen friends home for Christmas.

His dad, Corey, opened his envelope and read.

Dear Mr. Lewis: It has come to our attention that you are of direct descent to the great lost Lewis bloodline. Long ago in your family history lies the fabled pirate legend the Lost Lewis, who was the last known person to hold the priceless Mayan artifact. Lewis shipwrecked somewhere along the north coast, leaving the artifact hidden by secrets known only to him and his relatives. It was believed he died before bearing children, but with recent findings we have found that information to be false. You, sir, are a descendant of that Lewis and are entitled to the legendary Lost Lewis treasure. Sign your name under the dotted line and send back with intent. The Lewis guild will update you on clues to the fabled Treasure. … Good luck, you will need it.

Included in the letter was a link to a Google Drive with the first round of clues. Corey looked at his son and grinned.

“This is going to be so much fun!”

His son smiled back.

“I hope so; I’ve been working on it for two years.”

Courtesy of Corey Lewis

That was a month ago. Today, Corey Lewis sits in his tae kwon do studio in nearby Arcata, about a 20-minute drive from the waters where his oldest son presumably drowned. Weak January sunlight filters into the space that doubled as Hunter and his brother Bodie’s favorite place to play endless games of Dungeons & Dragons, with Hunter always serving as dungeon master. Corey is an accomplished martial-arts expert, a former tenured professor, and now a life coach and the author of a handful of self-help books. But right now he looks tired and spent. He grew old the moment he received the call. Still, Corey never grows tired of talking about his boy. He speaks of him in the present tense.

“I always say that Hunter is Corey 2.0.” He smiles. “Like me but without the glitches.” He pauses for a moment. “He was definitely kinder and braver than me.”

Hunter was genetically destined to live like he was the star of his own action film. It was in his blood. Corey’s grandfather was killed in a motorcycle accident when Corey’s father was little. Corey’s mother, Nancy, was a rodeo star back in Cheyenne, Wyoming, during the Sixties. She then married Lon Lewis, a veterinary nutritionist who did triathlons well into his seventies. They still drive every summer with their horses in a trailer from Topeka, Kansas, to their Colorado ranch 12 hours away. Corey met Micki, Hunter’s mother, while he was working on the rugged Pacific Crest Trail. They moved in together in Reno, Nevada, where Corey was working on his Ph.D. in creative writing. They hiked and camped in the desert, going off the grid for days. Micki was always slightly more cautious than Corey, although that is a sliding scale in the Lewis family, as indicated by her swimming from Alcatraz to the San Francisco waterfront in her thirties, after Hunter was born. She loved Corey’s daring side and tolerated the excesses, like the time he was arrested for wandering alone in an Atlanta subway tunnel after a buddy’s kickboxing fight.

“I couldn’t really complain,” Micki tells me. “That kind of behavior is what attracted me to him in the first place.”

When Micki got pregnant in 1999, the couple paused for a second, wondering how a baby would fit into their lifestyle. In the end, they just threw the baby they named Hunter into a sling and kept camping and climbing. Among his first words were “Higher, faster.” Corey obliged and built Hunter a mini roller coaster in their driveway.

Courtesy of Corey Lewis

The following year, Corey was offered a professorship at Humboldt State University, and the family immediately fell in love with the area where giant redwoods mesh with jagged cliffs before conceding to wild beaches along the Pacific Ocean. The family embraced the hippie vibe of the unspoiled country and began their exploration on long weekend hikes.

Corey started reading The Hobbit to Hunter when he was five, his baby brother, Bodie, sleeping nearby in his crib. Corey’s firstborn was always trying to escape the Lewis backyard, with his mom and dad screaming “Hunter!” Eventually, Hunter met a neighbor who remarked, “So this is the Hunter I’ve been hearing about so much.”

In elementary school, Hunter became obsessed with the treasure-seeking boys in The Goonies. He would have fit in well with those fictional lost boys — he already had a reputation at school as a curious kid with a loud laugh that could erupt at any time.

When the boys got a little older, Corey took them to Humboldt State and started teaching them parkour, an athletic endeavor in which you jump from roof to roof or rock to rock, theoretically minimizing the risk by looking before you leap, contemplating all the potential outcomes.

Corey taught wilderness safety to students at Humboldt and urged his boys to take risks but not be reckless. Sometimes it took, sometimes it did not.

There were occasional signposts of the dangers of living an interesting life. When Hunter was 10, Micki and Corey took the boys to Mexico to meet Corey’s parents at a beach resort. Still a daredevil at 70, Corey’s dad was body surfing when a rogue wave slammed his skull into the sand. His mother screamed, and Corey dragged his dad out of the water. He wasn’t breathing.

The family had just lost Corey’s brother to cancer. Corey was certain neither he nor his mother could survive another tragedy. A man on the beach started administering CPR, but according to Corey, his father didn’t come back until he and Micki took over the chest compressions. “I think it was the visceral connection that a father and son have that brought him back,” says Corey.

Hunter watched in silence, telling his scared little brother that everything would be OK. It was Dec. 31, 2009, 12 years before Hunter disappeared.

Humboldt County is a loosey-goosey place that fitted the Lewis family well. It often reeks of weed, not because everyone is smoking it, but because the smell wafts out of the redwoods from large farms just a short drive from the coast. On a windy January day, Corey takes me for a drive along the coast and tells me about a man who once owed him $900 for life-coaching sessions. The man said he needed to collect it from a farmer who had bought some property from him and lived outside of town. He asked Corey to come along. Corey agreed, and after 45 minutes of driving, the two found themselves on a remote rural road where he and his friend were met by men on ATVs with rifles on their backs. They left with the money.

“That was not my scene,” Corey tells me as he steers his Jeep down a windy road. “It’s a little bit like the Wild West out here.”

He then slows down to say hello to a haggard but healthy old man in a wet suit, with a surfboard under his arm. The old man tries to find the right words.

“I’m so sorry about Hunter. It is just . . .”

He trails off, and Corey looks at the man with kind eyes.

“I know, thank you.”

We drive in silence for a minute before pulling into a beach parking lot. Corey laughs.

“That was the guy who owed me $900.”

We are at Moonstone Beach, and Corey wants to show me where he held a treasure hunt for Hunter on his 10th birthday. It was shortly after Corey and Micki told the boys they were divorcing. On a particularly dark day, Corey wept in front of his boys, and then apologized for breaking down in front of them.

“That’s OK, Dad,” said Hunter. “Everybody has to cry.”

Hunter remained a boy without guile or shame even after reaching adolescence. Micki would sometimes substitute-teach at his middle school, and he’d scream “Hi, Mommy” across the crowded halls.

“Whenever he was leaving the house, he’d circle back for a second hug and ‘I love you,’ ” Corey tells me as we walk in the wind. “It never stopped until he was gone.”

Hunter wasn’t stymied by typical kid problems. His best friend Zane was going to Canada with the school band and Hunter wanted to go, so he learned how to play percussion in six weeks. To him, life was just a riddle to be solved. Corey encouraged his curiosity, constructing clues and maps and leading his two boys on treasure hunts both on his parents’ Colorado ranch and on the beaches of Humboldt County.

“Hunter wanted people to face their fears and become the person they knew they could be,” his father says. “Whenever he left the house he circled back for a second hug ‘I love you.’”

We step through wet sand, and I follow Corey as he dips his head and enters a cave. It is a dark and serene hole, and the ocean’s thunder melts away. This was where Corey hid the treasure on Hunter’s 10th birthday. We enjoy the respite from the elements, and Corey speaks quietly.

“I had a cigar box I’d had as a kid, and I used it as a treasure chest for the boys.”

Hunter, Bodie, and his friends followed the clues. As usual, Hunter found the treasure that consisted of a few dollars and some chocolate gold coins. A few years later, Corey gave Hunter the box after another treasure hunt at his parents’ Colorado place.

“He acted like the box was a treasure in itself.”

We walk back toward the parking lot and briefly stop at a cliff that played a role in the treasure hunt. One of the clues led Hunter’s friend Michael Santos here to retrieve a clue that was embedded into a crevice. Alas, Santos was afraid of heights and didn’t want to rappel down and grab it. Hunter spent two hours cajoling his friend and taught him how to rappel and grab the clue.

“Hunter wanted people to face their fears and become the person he knew they could be,” Corey says.

I wonder aloud how Hunter had hidden the clue by himself in the first place. Corey sighs.

“He probably came out here and did it by himself. Not the best idea.”

We drive back into town on the 101, shading our eyes from the setting sun flitting through the redwoods. Eventually, Corey mentions that only one other thing washed ashore besides the splinters of the canoe. It was the cigar box turned treasure chest.

Nothing could stop Hunter Lewis except for a pandemic. The beauty of California is it’s so big that Hunter could decide to go to college 600 miles away and still qualify for in-state tuition. His boyhood dream of flying and going to space was no longer kid stuff. Cal State Long Beach had an excellent aerospace program and was geographically located in a city that was essential to America’s space industry.

Hunter made friends before his parents had left his dorm parking lot. Home on Christmas break, he talked excitedly about how the Pacific Ocean was 30 degrees warmer in Long Beach than in Humboldt, and wasn’t it weird that it was the same ocean? He began working on his father to let him start taking flying lessons, cagily suggesting a pilot license was one of the prerequisites for aspiring astronauts. Corey told Hunter he would look into it.

And then the plague came. By the spring of 2020, Hunter was back home in Humboldt taking classes remotely and living in the small cottage behind the house that Corey shares with his second wife, Jessica, and her two daughters. Hunter was slowly going bananas, cut off from his future and his new life. It was anathema to everything his father had taught him. “My dad has a saying where if you want to pursue something, don’t do it in the future, do it now,” Hunter told a classmate. “Now’s the time for everything.” To break up the monotony, he went camping in the California mountains with his friends Dakota and Zane, telling his dad that they would figure out how to put chains on his truck when they got there. They returned safely, but the trip only made him more restless.

In the fall, he and his parents decided he should go back to Long Beach, even though his classes would still be over Zoom. He moved into an apartment building and befriended a middle-aged gay man who he referred to as his “guncle.” The man taught Hunter that taking out his stinking garbage was a good thing, and that playing video games at 3 a.m. and laughing loudly above his bedroom was a bad thing.

And he flew. Corey had taken flying lessons and let Hunter tag along, but never got his license. Hunter was different; he felt more alive than he did jumping from rock to rock in the mountains. Once he got his license, he took a classmate, Nathan Tung, along on some flights. Tung shot a short documentary about him. “As soon as I step into the airplane everything else that has been going on in my day just leaves my mind,” says Hunter to the camera. “I’m not thinking about what I need to do tomorrow.”

Tung didn’t mention in his video that his door flew open after taking off and that Hunter gently admonished him to be more careful. Five minutes later, Hunter’s door flew open as well, and they both laughed.

That October, Hunter and a dozen other college students rented a big house outside Zion National Park in Utah. He knew most of the other kids, but not all of them. One of the strangers was Kinsley Rolph, a journalism student and hockey player at Chapman University in Orange County, about 20 miles from Long Beach. She first spotted Hunter paddleboarding near the house, and was immediately taken. She looked forward to watching him and some of the others play music. Before coming down for the show, Kinsley stepped into the bathroom that had been designated for the guys.

She didn’t come out for an hour. She had clogged the toilet and was too embarrassed to tell anyone. Hunter spotted her and asked why she had missed the band. Near tears, Kinsley confessed her sin. Hunter just laughed his big laugh and told her it was no big deal. He got a plunger and fixed the toilet.

Courtesy of Corey Lewis

After that, the two were rarely apart. On the second night of their trip, Kinsley froze on a climb, not out of fear — her hands were stiffening because she’d forgotten her thyroid medication. Helmetless, Hunter climbed up and helped her down. It wasn’t long before Kinsley was spending almost all of her nights at his apartment.

“The pandemic was terrible, but it let us spend 24 hours a day together,” Kinsley tells me in a park not far from Hunter’s Long Beach apartment. “We did our classes over Zoom, so we didn’t need to ever be apart.” Our conversation is occasionally interrupted by planes landing at Long Beach Airport. She looks up and smiles.

“Hunter loved to come here and watch the planes,” Kinsley says. “Once, he flew me home from a hockey game in Santa Barbara. I thought my coach would be mad because I didn’t take the team bus, but he was just ‘I’ve got to meet this guy.’ ”

Most nights they made dinner before retreating to bed, where their vigorous activities broke two bed frames. “After that, we decided to leave the bed on the floor,” says Kinsley. “But now I’m making a bookshelf from the broken parts.”

The two met each other’s families, hers in suburban Boston and his in Humboldt County. On one visit, Hunter took her on a tour of his favorite places, heading up on a deserted road above Trinidad Beach. He parked the car, and they hiked a few hundred yards holding hands until they emerged into a clearing. Kinsley’s jaw dropped. Suddenly, they were looking down on the Pacific Ocean, and he pointed out his favorite rocks and reefs. He sat down and looked out toward the horizon.

“This is my favorite place.”

He wasn’t exaggerating. He often came here to think and draw. Hunter had his senior-year photos taken there, but didn’t tell his parents where they were shot. It was his place alone.

That day, he pulled out a notebook and started sketching, using Kinsley as an easel while he traced the reefs of Bird Rock, Small Rock, and Flat Iron Rock, maybe 500 yards from Trinidad Beach. Kinsley knew better than to ask what he was drawing. She knew he had been working on a big project since a few months into their relationship, but not much more. He kept his ideas in a black notebook that never left his side. Hunter told Kinsley not to guess because it would ruin the surprise. She agreed.

They shared their dreams: Kinsley wanted to be a TV reporter, and Hunter, well, he wanted to do so many things. One time, Kinsley remembers, Hunter began talking about how he wanted to die.

“I want it to be while I’m doing something epic, maybe a plane crash or something.”

For four days, Hunter watched with glee as his friends searched the area for clues, roaming from the mud of Humboldt State’s Frisbee-golf course to a crevice in purportedly the world’s tallest totem pole, in nearby McKinleyville. He’d help if the competitors wanted, telling his brother if he was getting hot or cold while searching for a clue on an abandoned railway bridge not far from their boyhood home. But then he’d vanish for hours, hiding the next round of clues all over the county, gunning his red Jeep up and down the 101. At night, he’d sit on the couch at his dad’s house as Kinsley and his father tried to cadge hints out of him. He would just grin and shake his head no.

The hunt grew curiouser and curiouser. One of the second tier of clues was a link to a recording of Hunter playing the Scooby-Doo theme song. While Hunter filmed, Corey listened with Kinsley and said he didn’t notice anything strange, but she had heard the song before, and this sounded different. Kinsley is deaf in one ear, so she heard the track in her own version of mono. Using an audio-edit-function app, she was able to isolate tracks and find one on which he had written on the file’s spectrogram “S3 E12 2:00 Blue Lake.” Hunter groaned, he meant for it to take much longer to solve.

Kinsley and Corey had formed an alliance, and they tried to figure out what the numbers meant: a secret code or an important date? They struggled for hours before Kinsley realized they were overthinking things. Scooby-Doo was one of their favorite shows. At two minutes into Season Three, Episode 12, Shaggy and Scooby are trying to build a treehouse sandcastle.

She happily shouted at Corey, “I’ve got it.”

In front, shrouded by an evergreen, was an old treehouse that Hunter and Bodie had played in as boys. Kinsley feared the rotten tree, so she waited until morning. After breakfast, she began to climb the tree. Hunter filmed her and shouted encouragement. She entered the treehouse but found nothing.

“Just a little higher,” shouted Hunter.

She stood up and pushed her hand through the rotting treehouse roof and saw a rope with a white key that Hunter made with his 3D printer. She climbed down the tree. Hunter gave her a hug.

“You were so brave. I knew you could do it.”

On the key was a clue written in Braille. Corey and Kinsley went back inside and Googled a Braille alphabet and spent an hour spelling out the words: “From Isaac to Rene.”

They knew Hunter loved science and math, and Isaac Newton and René Descartes were two of his heroes. But they were stuck. What did it mean?

“Hunter loved these stories of amazing journeys where everyone is a hero and makes a great escape,” his mom says. “But Hunter didn’t escape.”

Meanwhile, Hunter knew it was only a matter of time before the contestants would be closing in on the actual treasure. There was just one problem: He hadn’t yet put it into place. He knew it was time to kick it into gear.

Kinsley and Corey never figured out the meaning of the “Isaac to Rene” clue. There was no one to give them a hint. Hunter was gone by then.

Kinsley and Hunter woke up slowly on the morning of Dec. 30. The previous day had been epic. Kinsley had met up with Hunter’s best friend Zane, and they decided to hunt down a riddle that had led them to the Frisbee-golf course on the campus of Humboldt State. Hunter tagged along for filming purposes, and laughed as they tried to decipher six numbers that Hunter had placed on target baskets on the course. Growing frustrated, they headed with Hunter in tow to another friend’s house.

There, Zane looked at clues from the next tier, three pages of text from Hunter’s favorite books: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Martian, and Endurance, the classic retelling of Ernest Shackelton and his crew’s miraculous escape from the Antarctic. Zane remembered that the stranded Martian astronaut was able to communicate with Earth by substituting a series of number patterns for letters and words. He began using the code from the book and realized that the numbers spelled out “Pump Four,” a water station in a dried-up creek at a different Frisbee-golf course.

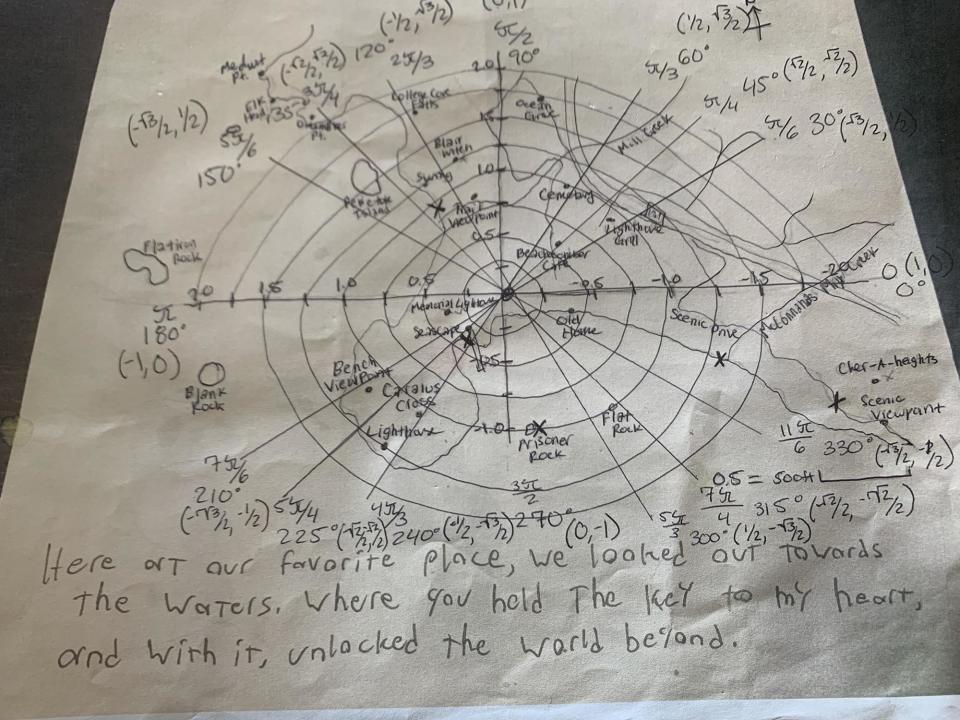

They drove back, and in the dark walked with flashlights until they found six more numbers posted on the station. Zane deciphered them to mean “Under Four Bridge.” They ran to the fourth hole and noticed a small walking bridge across a creek. Zane slid under and found a Mason jar. In it was a map of Trinidad Beach with a few words written in ornate letters: Here at our favorite place, we looked out towards the waters. Where you held the key to my heart, and with it, unlocked the world beyond.

It was nearly 10 p.m., so everyone headed back to the house. They would deal with the map tomorrow. That night, they played Hunty-opoly, a version of Monopoly that Kinsley had created for her boyfriend, with his favorite places — like the Long Beach Flying Club — standing in for Boardwalk. Before turning in, Hunter asked his dad if he could borrow his pickup truck in the morning so that Kinsley could drive his Jeep. Corey said sure, and everyone turned in.

In the morning, Hunter said goodbye before circling back to get another kiss from Kinsley.

“I love you.”

She smiled.

“Be safe, be careful. I love you too.”

Hunter walked over to the side of the house, where he lifted up a canoe that he and Corey had used on some river adventures. He walked by the kitchen window, where Corey’s wife, Jessica, saw him load it into his dad’s truck. She didn’t give it a second thought.

Around 10 a.m., Kinsley took the map and met some friends of Hunter’s at Zane’s house. They then headed down to Trinidad Beach. For hours, they trudged along the beach looking at the map, but they didn’t know what they were searching for. Kinsley sent Hunter a playful text detailing their frustration, but, strangely, he didn’t respond. A little later, she and Zane noticed Corey’s truck and decided to leave Trinidad Beach. They didn’t want Hunter to think they were spying on him. After some more wanderings and another unanswered text, they drove back to Trinidad. Corey’s truck was still there. The winter sun was setting, and Kinsley grew concerned. They noticed Hunter’s phone was on the front seat. That’s when Kinsley called Corey and told him she was at the truck but there was no sign of Hunter.

He immediately called the police. Then he asked Jessica if she had seen Hunter that morning. She told him she saw him loading the family canoe into the truck. Corey immediately put it together. He jumped into his car and just kept saying “No, no, no, no.”

The next two days were an agonizing blur. An impromptu search crew put on headlamps and scoured the beach in the blackness that first night. Kinsley went back to the house around midnight. She sat on the bed holding one of Hunter’s sweatshirts — she knew he would be cold when they found him — and waited until it was 6 a.m. in Massachusetts, then called her mother. Kinsley’s mom had a hard time understanding her daughter because Kinsley was crying so hard. She promised to get on a flight as soon as she could.

Hundreds of locals mobilized and began scouring nearby beaches and coves, some that could only be accessed with climbing ropes. Helicopters hovered overhead and divers searched the sea. But Corey didn’t have much hope. The day Hunter disappeared had been cold, the water was frigid, and Hunter didn’t take his wet suit.

His last hope was extinguished when another boater reported seeing Hunter paddling out of Trinidad Harbor, turning around the point and heading into unprotected waters. The next day, Corey hired a boat and headed in the direction where Hunter was last seen. The boat bobbed as it approached Flatiron Rock. Corey asked the captain if he could get closer.

“I can’t — there’s rocks just under the water that will tear us apart.”

Later that afternoon, a call came into Corey. Shards of the canoe had been found on an inaccessible beach, about a half-mile away.

Corey and Kinsley talked the next morning. They were exhausted from grief and knew they didn’t want to be the ones who found Hunter if his body washed ashore. Instead they decided to solve the Lewis treasure. But all they had was the map and the key with the Newton and Descartes clue. They walked the hills around Trinidad Beach for hours. Still nothing.

Courtesy of Corey Lewis

In front of Kinsley was the same view she had seen with Hunter. Kinsley and Corey looked at the ocean, the sun, and three distant rocks a few hundred yards offshore. Instinctively, Corey pulled out the key. He held it in front of him. The key’s nubs lined up with the two smaller rocks. The keyhole gave him an unobstructed view of Flatiron Rock. And instantly he knew what had happened: His boy had paddled out toward the rock to stash the final treasure.

The frail canoe either capsized or broke up on the reefs. Hunter wouldn’t have survived 15 minutes in the icy waters. All Corey could think was “Why?”

“He knew that the area around Flat Iron Rock was dangerous. We’d been talking about how crazy the ocean could turn since he was a little boy,” Corey tells me. “I don’t know why he would take such a risk.”

But Corey also knew what Hunter would say.

“Why not?”

It provided no consolation.

I almost didn’t write this story. It was simultaneously too sad and too cinematic. I worried that everyone would concentrate on the ingenious and, yes, the joy of the treasure hunt. They would skim over the fact that a promising young man made a terrible mistake that will forever haunt his family and friends. I talk to Corey about it, and he admits he fell victim to it as well. Friends have asked him who should play him in the inevitable movie version of Hunter’s life.

“It’s fun for a minute,” says Corey. “And then I remember that I won’t ever see him again, and it kills me.”

I had some personal experience with this. My father was a Navy pilot who was killed in a plane crash off the USS Kitty Hawk in the Indian Ocean when I was 13. All I heard was that my father died doing something he loved more than life itself. Later, I learned he was probably flying too low and too fast for the conditions. My family was left with nothing but a folded American flag and a marker at Arlington National Cemetery.

Those memories sometimes overwhelmed me as I thought about Hunter. It left me sleepless, obsessing over my eight-year-old son’s safety, and with writer’s block for the first time in my life.

I kept flashing back to the day Corey took me, Micki, and his parents up to Hunter’s spot. We trudged across the same trail Hunter did, pushing the same brush and branches out of our eyes before emerging into his Eden.

We all gasped at the beauty. I held the key up and saw how it aligned with Flatiron Rock. It was a half-mile offshore, but looked tantalizingly close to the beach from here. His grandmother smiled as she gazed into the distance.

“Someone asked me about him taking risks, and I said, ‘Hey, he’s a Lewis.’”

Micki joked that she would come back and hang up a hammock and live there. We made small talk about Hunter, and Micki said she was rereading The Martian and Endurance.

“Hunter loved these stories of amazing journeys where everyone is a hero and makes a great escape,” Micki said, her voice cracking. “But Hunter didn’t escape, he didn’t come back.” We all fell silent and just listened to the waves and the wind rushing through the trees.

I talked to Corey a couple of weeks after I left Humboldt County. He told me he recently returned to Hunter’s place by himself and had a conversation with his son.

“Hunter, why did you have to go out in the canoe? Why did you have to die? We had so much more to do.”

“Would you like me to take a year and die from cancer? Or die in a meaningless car crash? Or be a victim and make someone else a villain and ruin their life?”

“But Hunter, why so soon? We had so many things left to do.”

“Dad, I went in the most epic, beautiful way possible. And I kept you all in the dark. I kept it all a secret from you. So none of you could blame yourself. And now I am the Lost Lewis treasure forever.”

Then Corey got into his son’s Jeep and drove home.

Best of Rolling Stone