Catie McKee, Dan McNamara, and their boss Marc Rosenthal had millions of dollars riding on Crystal Mall in Waterford, Connecticut. The trio worked at MP Securitized Credit Partners, a tiny Wall Street hedge fund, and they’d stopped by the typical middle class shopping center in search of signs of life: Who was at JCPenney? Claire’s? Hot Topic? ThriftBois? What was up at VAPE CITY or BrowArt23? They couldn’t help but notice there was something depressing about the place: discounts galore, emptiness in every direction, a foreboding aura that signaled the end was near. It didn’t look good for anyone hoping for the mall’s success. But Rosenthal, McKee, and McNamara weren’t betting on Crystal Mall thriving—they were betting on it failing, and spectacularly.

It was October 2019. The threesome was in the business of betting against—or “shorting,” in financial jargon—commercial mortgage bonds, specifically those heavily weighted with debt issued to shopping malls. A year prior, in 2018, the team made a $2 billion bet that a series of shopping malls, including Crystal Mall, would eventually fail. If retail tenants vacated and the malls’ landlords defaulted on their mortgages, MP stood to make a killing. They had taken many trips like the one to Crystal Mall over the past two years: this downtrodden mall after that one, seeing firsthand the shopping centers, once the heart of the American retail sector that, they were certain, would soon be underwater.

It was a proposition which, in the age of Amazon, couldn’t possibly be considered risky on its face, but in the minds of traders on Wall Street, the threesome was taking a contrarian view: The conventional wisdom stood to reason that the debt propping up these shopping centers was stable, at least for now, whereas the team at MP was convinced that the malls’ landlords would default on their mortgages by 2022—and, most importantly, that if they didn’t have their bet placed now, they’d miss the chance at a huge payday.

After a long morning casing the storefronts, the team headed down the street to Olive Garden for a late lunch. The past ten months had proved to be near-fatal for their firm. A year into their trade, they hadn’t yet made a profit—in fact, they were losing millions of dollars every month. By the time McKee and McNamara took their boss to Crystal Mall, investors had pulled out of their fund, the small team was struggling to source more financing, and they even found themselves in a war over their trade with two big Wall Street investment firms. Although locked in a battle akin to David versus Goliath, Rosenthal’s excitement was palpable. It was his first mall tour, and to see the struggling center first-hand reinvigorated the kind of macabre confidence that accompanies any short bet. “He was like a little kid in a candy store,” McNamara remembered. Rosenthal told his employees that he wanted to drive deeper into Connecticut, to check out another struggling mall. He pulled out his phone. “It’s only an hour away,” Rosenthal said, pointing to his screen. “Let’s go!” It was late afternoon on a Friday, so McKee and McNamara convinced their boss to save it for another day. The team finished eating and drove back to Manhattan, their conviction cemented that they were on the right side of the trade.

The shopping mall began with the suburbs. In 1956, the Southdale Center, America’s first indoor mall, opened in Edina, Minnesota, just outside of Minneapolis. Life called it “The Splashiest Center in the U.S.,” and praised its “goldfish pond, birds, art and 10 acres of stores all...under one Minnesota roof.” The famed architect Victor Gruen designed Southdale, and his inspiration came from a place of disgust. He hated what American suburbia had become, likening their roads, to The New Yorker's Malcolm Gladwell, in a 2004 piece, to “avenues of horror...flanked by the greatest collection of vulgarity—billboards, motels, gas stations, shanties, car lots, miscellaneous industrial equipment, hot dog stands, wayside stores—ever collected by mankind.” He hoped the mall, a centralized retail destination, would fix that. (It did, for a while, until the veneer of “mall rats” and Black Friday stampedes diminished the allure of malls.) The indoor shopping craze soon spread to every corner of the United States. Three hundred malls opened by 1970, mainly catering to homemakers. The women could pop down, buy all the things they needed for their household, and potentially snag a new outfit along the way. The trend continued and, by 2017, at its peak, America was home to over 1,200 malls.

None of this—the Southdale Center, Victor Gruen, or how the mall transformed suburban consumerism—was top of mind for McKee when, in 2013, at age 25, she was hired at MP Securitized Credit Partners as a commercial mortgage-backed securities credit analyst. She spent hours each day scrutinizing pools of business mortgages that had been bundled into bonds and were bought and sold on Wall Street. She was looking for good deals to buy into, but also hairline cracks that could, over time and under the right conditions, break open like a faultline, giving anyone with a short position a chance at a huge payday.

McKee grew up in Stillwater, New Jersey, population 3,893, to a mother who taught pre-school and a father who owned a moving company. A precocious student, she earned a perfect score on the SAT Math, captained the field hockey team, and enrolled at Georgetown University. “By the time she was five years old, she was already smart and stubborn,” Ed Abrams, McKee’s father, said. “I’d tell her things she couldn’t do, but by the time we were done debating, I was the one who had given up and was feeling guilty. I told her she should become a lawyer.” McKee instead pursued a career in finance. She interned at UBS Bank and then landed a position in the research department at Bank of America. She wanted to be a part of the action, but got denied a position on the trading desk. Then she met Dan McNamara; when he offered her a spot on the MP team, she didn’t hesitate.

Dan McNamara—a diligent and gregarious Bostonian, broad-chested and wide-smiled—had joined MP in 2013 from the French bank Société Générale, to oversee commercial mortgage-backed securities. “He was young and hungry,” Rosenthal said. “We knew he’d fit in.” The group spent the next few years building up their portfolio, mainly investing in distressed assets, until, one day, in 2017, a curious tip came across their desks from Eric Yip, the then-chief investment officer at the newly-launched hedge fund Alder Hill Management.

Yip, who was born in Hong Kong and had moved to New Jersey at age five, practically grew up at the local mall, where his parents owned a shop. He even worked at Banana Republic during college. He traveled around the country, sometimes with his family in tow, and investigated the shopping centers first-hand. He became convinced that they were destined to fail. (Yip declined to comment to Esquire.) By 2017, it was obvious to anyone with an internet connection that e-commerce was killing brick-and-mortar shopping—especially when it came to malls. E-commerce’s share of total retail sales tripled between 2007 and 2018, big-box tenants like Toys ‘R’ Us had gone bankrupt, the physical size of malls was bloated compared to the amount of foot traffic they obtained, and malls in second-tier markets (which were less likely to have an anchor of stable tenants) were declining faster than their urban counterparts. Credit Suisse was predicting that by 2022 a quarter of all U.S. malls would close. To many, the transition seemed almost too obvious to even point out, but not everyone thought to short its debt. In a January, 2017, research paper, Yip called mall debt a “toxic cocktail,” adding that many high-risk loans are “backed by malls that we believe are highly likely to become ‘dead malls’ over the next several years.”

Shopping mall landlords are just like your average homeowner; they need mortgages. Much of their mortgage debt has been packaged together by big banks with other commercial real estate mortgages (hotels, office buildings, etc.) into “securities” that are actively bought and sold on Wall Street through the $1.4 trillion commercial mortgage-backed securities—or CMBS—market. These securities bundle dozens of loans into one convenient investment (while offloading risk for the lender), a place where you can park your money and theoretically receive a steady return as the underlying debt is repaid. It’s kind of like buying a government bond, but instead of the U.S. Treasury paying back the debt, it’s landlords who own commercial real estate.

By the end of 2017, Yip had identified two specific securities heavily weighted with risky mall debt—and became the first to short them. News of Yip’s trade spread like wildfire, and McKee and McNamara saw merit in his hunch. “Our take was, ‘We agree with your thesis, but we think you are a bit early,’” McNamara recalled thinking of the trade, adding that, because much of the debt matured—that is, was scheduled to be paid off—in 2022, he thought it’d be a little while longer before the bonds started to crumble. Nonetheless, it was only a matter of time, McNamara and McKee felt, before the tenants left the storefronts vacant and the malls defaulted on their mortgage debts.

Before MP decided to jump in, however, McKee took a few field trips. She knew the nuts and bolts of the malls’ on-paper financials, but her instincts told her that, if she looked at the malls from a different vantage point, she’d see a clearer picture. She drove to Crystal Mall in Connecticut; Poughkeepsie Galleria, Crossgates Mall, and Eastview Mall in New York State; Emerald Square Mall in Massachusetts; and Chesterfield Towne Center in Virginia. She flew out to California and checked out Solano Mall. She hit up the Shoppes at Buckland Hills on the drive back from a skiing trip in Vermont, and scouted Concord Mills Mall while visiting her grandfather in North Carolina. “One mall had a community room, just a series of random desks. It was this weird, free WeWork,” McKee said. “They would rather give free space than list it as vacant.” (McNamara called this “occupancy fraud.”) On another trip, she came across an unattended trampoline with a bungee cord strapped to it—what she considered a glaring safety hazard. McKee snapped some pictures, but was quickly approached by a security guard who demanded that she delete the photographs.

Rosenthal and McNamara, meanwhile, convinced Josh Nester, MP’s residential mortgage specialist to visit Fashion Outlets in Primm, Nevada, 30 minutes south of Sin City. When Nester arrived, he instinctively took out his phone to take a picture of his rental car so he could remember where he parked before looking around to discover he was the only car in the lot. “I go in, and I don’t see anybody for five minutes—an employee, a customer, nobody,” Nester said. “I joked that I should’ve gotten hazard pay to go to this place. It was like something out of a zombie movie.”

Then, in October 2018, Sears declared bankruptcy, and they decided it was time. Here was the scheme: MP built a position against two slices—called “tranches” in Wall-Street speak—of mall debt with, they thought, a relatively low likelihood of being repaid: CMBX.6 BB and BBB-, which were filled with roughly $2 billion worth of debt, an outsized chunk of which was issued to 39 struggling shopping malls. They bought credit default swaps on the block of debt, which amount to insurance policies on the bonds. If the bonds went completely bust—similar to, say, your house burning down—they would be owed their entire value in cash. But even if the tranches decreased in value, MP’s insurance would be worth more and they could sell the swaps for a profit. In any case, it was an asymmetric bet: the downside risk was confined to what they’d have to pay to hold the insurance, but the potential payout was many multiples of that amount—theoretically in the billions.

It fell to Dan McNamara to make the trade. He called brokers at Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, and Credit Suisse to buy the credit default swaps. The brokers were intrigued by the prospect of a short, but they told McNamara point-blank that they thought it was a risky trade. “I remember multiple people saying, ‘Are you sure, Dan? It’s still too early. You’re pissing money away,’” he said. MP, however, held to their conviction. They bought the swaps. In the 2019 research paper that accompanied taking their position public, they wrote that “defaults and losses seem to be imminent.” Now all that had to do was wait.

Things did not immediately go according to plan. When you’re short a stock or a bond, you’re praying for pain in the markets, and if the Grim Reaper doesn’t show up, you’re going to pay for it—especially if you’ve purchased credit default swaps. They’re an expensive bet because, as with any insurance policy, MP had to pay a monthly premium against the value of the CMBX.6 tranches, which amounted to tens of millions of dollars per year—a significant accumulation for the small firm, which only had $250 million to play around with. To make matters worse, if the value of the bonds increased, so too did their insurance premiums. Eric Yip, who had been in the trade at least a full year longer than MP, found himself in the grip of this reality. Alder Hill was bleeding money, and the hemorrhaging caught up with his fund. In September, 2019, Yip backed out of the trade, swallowed the losses he had accrued, and shut down Alder Hill. Another firm, Sorin Capital, also shuttered its fund that traded in CMBX.

Things didn’t look much better for MP, who, thanks to the crushing premiums, found themselves in a 37 percent hole by the end of 2019—a roughly $92 million loss. “It felt like we were getting kicked in the teeth every single day,” McNamara said. Things became contentious with their pool of investors, who began pulling their money out of the fund. “It felt like a run on the bank,” Rosenthal said. “I said, ‘I need you to have confidence in me that we are right.’ [Investors] were like, ‘I don’t care.’” The firm had to lay off three employees. It was a dark time.

But it didn’t make sense: on paper, the underlying bonds were getting weaker—the malls continued to struggle—but their value in CMBX, the index that tracks their price, was going up. “We felt like Michael Burry,” McKee said, referencing the trader spotlighted in Michael Lewis’ bestseller The Big Short. “We joked that we were sitting in our basement banging on the drums,” McNamara added.

This was because two large mutual funds, AllianceBernstein and Putnam Investments, were on the other side of the trade—literally. Someone has to sell you credit default swaps (insurance isn’t created out of thin air), and although MP’s brokers didn’t explicitly come out and say that the two mutual funds were the ones selling the insurance, everyone at MP knew it. It was common knowledge that AllianceBernstein and Putnam thought the malls would survive, and had invested heavily into the CMBX.6 tranches. In effect, they were keeping the price of CMBX.6 high through sheer perception—and the size of their bet, which was reported to be upwards of $6 billion combined. “They made up a huge share of the market, so they were able to push the price around,” McKee said, adding that she and McNamara went around to large institutional investors and pitched their side of the trade, hoping they’d flex their muscles in the market. “We needed more soldiers to fight this battle,” she said. But they were rebuffed. In their minds, it was too risky a position to carry.

Four months after MP dropped their CMBX.6 research paper onto the Street, AllianceBernstein, led by Brian Phillips, director of commercial real estate credit research, issued their own research paper (51 pages, full color, fancy graphics), titled, “The Real Story Behind CMBX.6: Debunking the Next ‘Big Short.’” They wrote, “The CMBX.6. The acronym has splashed across headlines and become a source of controversy on Wall Street, [but] our research shows that the American shopping mall is evolving, not dying.” McKee was enraged. “I spent all weekend looking for mistakes and bad assumptions,” she said. “I made bullet points and sent them around to other hedge funds.”

A war had broken out between the longs and the shorts, and much of the tit-for-tat played out passive aggressively in the press. In 2018, Reuters wrote that Putnam Investments had been “winning—to the chagrin of hedge funds like Alder Hill Management LP that are on the other side of the bet,” with Putnam’s portfolio manager Brett Kozlowski disclosing that the fund was generating six percent annual returns on their CMBX.6 investment. Remember: When you sell insurance, you get to collect cash premiums every month, so this profit was coming directly from the nay-sayers’ credit default swaps. By boasting about their returns, Kozlowski was effectively rubbing it in the short-sellers’ faces.

In 2019, after Yip closed his fund, Business Insider picked up on the battle between MP and the mutual funds, quoting McNamara as saying the malls were “massively underwater,” and that McNamara believed that Putnam’s exposure to crumbling shopping mall debt could be higher than their financial disclosures revealed. It got more pointed in a subsequent Debtwire piece. “The fundamental question is why has CMBX held up?” an anonymous source told the trade publication. “It has everything to do with two managers who have taken a different view and have an endless amount of money to support it." (When I asked McNamara if he was behind the quote, he started laughing and said, “No comment.”) Shortly thereafter, AllianceBernstein’s Brian Phillips told The Wall Street Journal that short sellers were peddling a “false narrative,” adding, “they are focused on momentum rather than credit fundamentals.” It was a bare-knuckled brawl.

McKee, McNamara, and the rest of the MP team started taking it personally. They spent many evenings in 2019 brooding over beers and cocktails at Valbella, an Italian restaurant on the ground floor of their office building. Rosenthal pulled aside anyone who was even remotely tied to the CMBS market and chewed their ear off on how they were right and AllianceBernstein and Putnam were wrong. For McNamara, the trade seeped into his personal life. He lost 20 pounds. His wife, Jessica McNamara, told me his stress was palpable: “It was hard to watch him come home every day and be so frustrated,” she said. On a family outing to Vermont, McNamara was largely absent, sneaking away to call investors and persuade them to stick with the fund. In October, Jessica learned that she was pregnant with their second child.

Meanwhile, McKee was becoming known on Wall Street as “The Queen of Malls,” and other bearish hedge funds began asking her for advice on shorting CMBX.6. “All I did was talk about malls all day,” she said. This included portfolio managers working for the infamous billionaire activist investor Carl Icahn, who, by the end of 2019, had put on a $5 billion short position, arguably the largest by anyone on Wall Street. This went against conventional wisdom at the time, considering that the value of the mall debt was going up, but once word got out that Icahn had entered the ring, the trade was taken more seriously on Wall Street. “That made a lot of people stand up and say, ‘Hold on, we should look at this,’” McNamara said.

Icahn’s team had reportedly discovered the opportunity from none other than Eric Yip, who, some say, convinced Icahn to do the trade. “He turned a cow’s ear into silk,” said Manus Clancy, senior managing director at Trepp, a CMBS analytics firm. (After COVID-19 proved Icahn’s trade serendipitously fruitful, Clancy joked on the company’s podcast, “It’s like LeBron [James] winning a $30 million scratch-off.”) By early 2020, a handful of hedge funds had altogether purchased $11 billion worth of credit default swaps on the CMBX.6 tranches—a sum nearly six times greater than the value of the debt itself.

Increased popularity wouldn’t necessarily solve MP’s problems, however. Their investors felt comfortable with their other investments, but many just didn’t want to be exposed to their shopping mall short. McKee and McNamara had an idea. They convinced their bosses to let them start a subsidiary fund to that of MP Securitized Credit Partners, which they would call the MP Opportunity Fund. It would focus specifically on shorting CMBX.6, and would be only for investors who had the conviction to stomach the trade. “It took Marc about two minutes to say yes,” McNamara said. They gathered up a handful of investors who agreed to lock-up their money with the duo for three years. “Dan said, ‘Look, we have gone to see these malls. We know them inside and out,’” said Jordan Konicek, McNamara’s friend from college. “I trusted him, so I put more than half of my 401(k) into it.” Another close friend of McNamara’s stuffed ten percent of his net-worth into the fund. McNamara also secured one large institutional investor, who put in more than $15 million. McKee, McNamara, Rosenthal, and Nester even put some of their own money into the fund. They couldn’t pull out. It was do-or-die. They were all-in on the death of the American shopping mall.

On December 31, 2019, the World Health Organization picked up on a report that a “viral pneumonia” had begun spreading in Wuhan, China. By January 21, 2020, the first case of SARS-CoV-2, as the coronavirus came to be known, was detected in the United States. It was the beginning of a pandemic that would eventually claim, as of this writing, over 250,000 American lives and decimate the United States economy. But, back then, as a winter’s chill settled over New York City, McKee and McNamara had no idea that this once-in-a-century public health phenomenon would come to affect their trade so spectacularly. In fact, they were still worried that they would even be able to continue making the trade at all: the cash from their new pool of investors hadn’t yet been transferred into the Opportunity Fund’s account. They needed the cash to buy the new batch of credit default swaps.

In February, as stocks plummeted, the CMBS market started buckling under the weight of the impending pandemic. McNamara immediately called the largest investor of their new CMBX.6 short fund. “I need the money!” he pleaded. “I need the money now!”

McKee was freaking out, too. It was February 28, a Friday—a full month before COVID-19 would engulf the city—and she had taken the day off to move into a new apartment on the Upper West Side. Her new place was on the 8th floor and, after the first trip up, the elevator broke down. Her father and uncle had driven into Manhattan to help McKee and her husband, and everyone began schlepping boxes up the stairs. Her WiFi hadn’t yet been hooked up, so she couldn’t track the price of CMBX.6 or see if the money had landed in their account. “She was really anxious,” Ed Abrams, McKee’s father, said. “It was a crazy day.”

She ducked outside and frantically called Rosenthal. “‘We are going to miss it! Where is the wire?!” she yelled. “We are going to miss it!’” She was terrified that, if they waited too long, the tranches’ price would drop and they’d lose their opportunity to put on the trade.

“We are not going to miss it, Catie,” Rosenthal told her. “It’s going to zero, don’t you worry.”

The money came in just before the market closed. McNamara immediately called Goldman Sachs and used every penny they had to buy credit default swaps on the CMBX.6 tranches. “They didn’t think I was crazy this time around,” McNamara said. Everyone at MP was confident that the market’s fear of COVID-19 would make these bonds go bust—and fast. They were right.

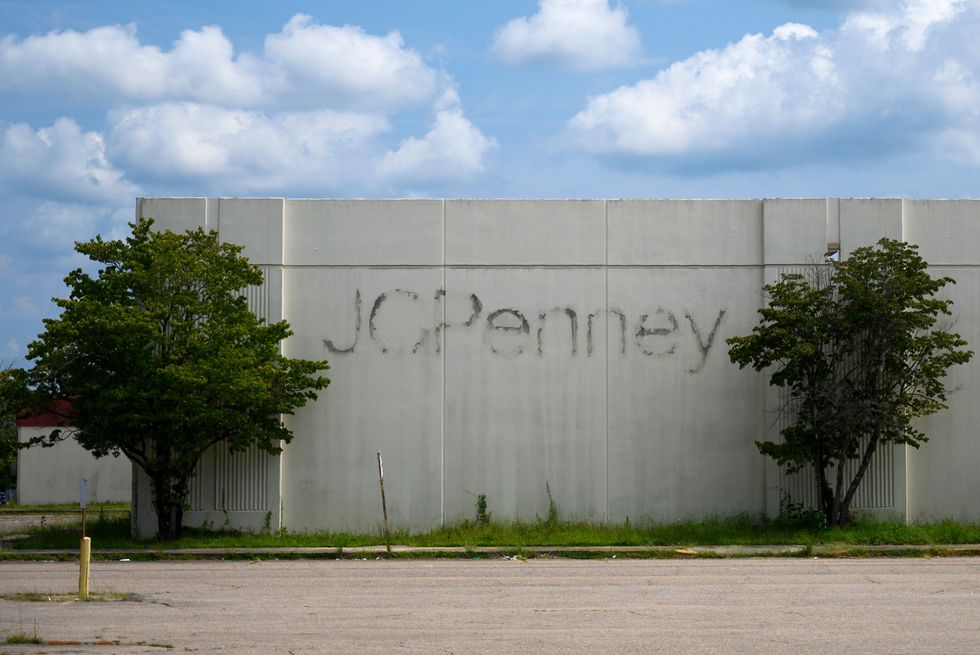

Between March and July, as businesses struggled to pay their rent, CMBS delinquencies, according to Trepp, increased by a staggering 492 percent, the value of the hotly contested CMBX.6 tranches were slashed in half, and the brick-and-mortar retail sector was on the verge of going belly-up. Large retailers like Gap stopped paying rent; Neiman Marcus, J.Crew, Brooks Brothers, Ann Taylor, Loft, Pier 1 Imports, GNC, and JCPenney (among many others) filed for bankruptcy; Victoria’s Secret was closing hundreds of stores and Lord & Taylor announced it was closing its doors for good and liquidating inventory; TJX and Macy's recorded losses of $5 billion and $2.5 billion, respectively; foot traffic for shopping malls plummeted to basically zero; and, in April, clothing sales fell 79 percent, the largest drop on record. “The economy has declared war on your aunt’s wardrobe,” Scott Galloway, marketing professor at New York University, mused on his podcast Pivot. As for Crystal Mall, Simon Property Group, its landlord, defaulted on the mortgage and is planning on handing over the keys to their special servicer.

CBL & Associates Properties Inc., which owns more than 100 shopping centers in the U.S., prepared to file for bankruptcy. Simon Property Group and Brookfield Property Partners, the largest mall landlords in the United States, took a more proactive approach and bought a stake in bankrupt JCPenney, effectively making the corporations both landlord and tenant. Green Street Advisors, a commercial real estate analytics firm, estimates that 50 percent of department stores in malls will close by next year and, according to Cushman Wakefield, as much as 2.4 billion square feet of storefront could become vacant by the end of 2022. CenterSquare’s Scott Crowe has a more pessimistic view. He thinks up to 80 percent of malls will eventually go dark.

In June, as the retail and lodging sectors imploded, putting pressure on the CMBS market to keep its head above water, over 100 members of Congress, led by Texas Representative Van Taylor, signed an open letter to the Trump Administration and the Federal Reserve, effectively asking for a CMBS bailout, imploring that a relief plan be devised “for these borrowers, who through no fault of their own, have experienced a significant drop in revenue on account of the COVID-19 pandemic and related governmental orders.” CMBS veterans disagreed with extending a helping hand. “It is bad legislation and wrong, plain and simple,” Ethan Penner, one of the founders of the CMBS market, wrote in a blog post on Medium. “Borrowing from the CMBS system became a forum for mostly the greedy and risk-loving, or the clueless, none of whom deserve a bailout.”

COVID-19 also revealed a dirty secret hidden in the crawlspace upon which many commercial mortgage-backed securities were built. A University of Texas at Austin study published in August claimed that banks knowingly inflated underwriting income for $650 billion worth of commercial real estate mortgages issued between 2013 and 2019, including by 5 percent or more for nearly a third of the roughly 40,000 loans. “A well-documented historical pattern is that fraud thrives in boom periods and is revealed in busts,” the university researchers wrote, adding that end investors were unaware of this hidden risk, a deception akin to buying a Ferrari secretly outfitted with a rusted-out Kia engine. It could be argued that CMBS had been a magic trick all along, with big banks one step ahead, luring investors to pick a card from a rigged deck. It took a global pandemic—an act of God—to reveal this financial sleight of hand.

As COVID-19 barrelled through the United States during the spring, imperiling small businesses and whole sectors of the American economy, Catie McKee and Dan McNamara tried to figure out how long they should stay in their trade. They took some profits in March for MP’s main fund, which still held a small CMBX.6 short position—all the pundits kept chatting away about a “V-shaped recovery,” which made them nervous—but, as the weeks went on, the CMBX.6 tranches kept trending downward. They had more time, and wanted to see just how low the bonds would go.

Across the battlefield, COVID-19 spelled disaster for AllianceBernstein and Putnam Investments, who, in a matter of weeks, saw more than $1 billion wiped from their balance sheets. Despite this, Gershon Distenfeld, AllianceBernstein’s co-head of fixed income, told Esther Fung of The Wall Street Journal in late March that they were still in the trade for the long term, with Brian Phillips adding, “We are running stress scenarios, ’08, ’09 type of stress scenarios, and we are still comfortable.” Putnam chimed in, too, saying that the fund “stands behind its investment thesis and has fully and accurately described that thesis and its risks to our clients.”

CMBX.6, however, has yet to recover, and the BB and BBB- tranches are still down nearly 40 percent year-to-date. “Their failure to truly rebound off May’s all-time lows signals a continued expectation of losses,” said Paul Shapiro, index product manager at IHS Markit, the market-data firm that created the CMBX index. “Long positions have reached a crossroads, and must now decide to cut their losses and unwind at current prices, or see the trade through and hope conditions improve.” Brian Phillips, who butted heads with the short-sellers left AllianceBernstein in June after fourteen years with the firm. (Phillips said that his departure had nothing to do with the CMBX index.)

When CMBX.6 hit bottom in May, Catie McKee and Dan McNamara decided to sell their credit default swaps and reap the profits. MP’s main fund, which includes other investments, was up roughly 75 percent year-to-date, a staggering turn of fate after a tumultuous run that nearly bankrupted the firm. McKee and McNamara’s sister fund, which was all-in on shorting CMBX.6, had it even better. They saw 120 percent returns after it was all said and done, an ungodly amount of profit considering that many hedge funds saw their capital cut in half when the stock market crashed. In just three months, the scrappy team and their black-sheep idea had brought in well over $100 million in profit for the fund and their investors (before filling the hole created by the previous year’s losses, of course). Carl Icahn, for his part, took home $1.3 billion.

A righteous person would say that making money off the back of a global pandemic is at best opportunistic and at worst downright immoral—that the ghoulish deus ex machina that made short-sellers rich included hundreds of thousands of people dying and widespread economic devastation—but McNamara doesn’t see it that way, especially considering that MP placed their bet over a year before COVID-19 began. “We knew one day that the balloon would pop,” McNamara said. “All COVID-19 did was speed up our thesis—the pin that pricked the balloon.” As for McKee, she felt a tinge of regret that the pandemic was the reason that their trade worked. “The catalyst we were hoping for was the opposite of a pandemic or a recession,” she said. “People will say, ‘You got lucky with the pandemic,’ but I don’t like that explanation. I want to be right because we worked our asses off to find this opportunity.” Moreover, according to McKee, short-sellers who investigate these complex securities can spot inefficiencies in the market, and potentially prevent investment firms that handle, say, retirement accounts from getting burned. “[These mall bonds] were priced for perfection at the onset, as if they wouldn’t take any losses, but when you look ten years forward, it’s a whole other issue,” she said. “They’re way riskier than most people thought.”

On June 8, two weeks after MP exited their trade, McNamara’s wife Jessica gave birth to their second child, a healthy baby boy named Christian. “He’s got a big head, just like me,” McNamara said. He took a week off of work to be with his wife and sons. “It was one of the best weeks ever,” he said. “It was a surreal moment, knowing that the craziness at work was over and I could focus on my two little guys.”

In August, McKee and her husband, Will, went on vacation to Nantucket. They ran into a family friend, Jack, who had introduced McKee to a colleague when the MP team was scouring for investors to back their CMBX.6 short. The colleague, McKee said, “acted like I was some college-aged intern that needed career advice,” and declined to invest. Jack asked her how the trade had panned out. McKee told him it ended up being a home run. Will’s godfather, Barry McCarthy, former CFO of Netflix and Spotify, and in whose house they were staying, overheard the conversation.

“What’s the next big idea?” McCarthy asked McKee.

“I don’t have one yet,” she said.

“Well, when you find it,” he told her, “make sure I’m the first person you call.”

Ian Frisch is a Brooklyn-based journalist and the author of MAGIC IS DEAD: My Journey Into the World's Most Secretive Society of Magicians. He has written for The New Yorker, The New York Times, and New York Magazine, among others.