August 20, 2014

Researchers at the University of Florida have developed a surgical pin made from magnesium that can degrade in the body at controlled rates over time.

"We don't always want to put in a metal implant and leave it there forever," Michele Manual, an associate professor of materials science and engineering, said in a university press release out Tuesday.

"The idea with this pin is that it would dissolve over time, and after it's finished, your body is basically in the same state it was before you had an injury," Manuel said.

In lab tests, Manuel has discovered several advantages over pins presently made from plastic, stainless steel, and titanium. Its biodegradable properties allow the body to remove the pin naturally, avoiding another invasive procedure to remove the pin. Because the pin is made of magnesium, it can also function as a natural nutrient, as magnesium is a mineral that helps build bone in the body.

"Everybody knows someone who has an implant in their body that they wish wasn't there," Manuel said. "Surgical pins don't have to become permanent fixtures in the body. Many people take magnesium supplements, so this is a good orthopedic application. It's not only an implant that serves a medical need in terms of fixing bones, it's also serving a nutritional need as well."

Recently, Manuel began inserting the magnesium pin into the tibia of rats in various lab tests. X-rays show the rate at which the magnesium pins dissolve, and at six weeks the new bone is indistinguishable from the bone before the break. The magnesium can also function as a coating for an implant to promote bone growth.

Manuel's prototype is just the latest in biodegradable materials used in bone reconstruction, and is another step in the direction of using magnesium as a primary material in orthopedic implants. The biggest stumbling block in the application of magnesium is controlling the rate at which it breaks down. This is important as magnesium has a potentially dangerous byproduct in the form of hydrogen, which can cause problems if it is released in large quantities.

"Your body can handle the hydrogen, just not in large doses, so pockets form," Manuel said. "If we can slow down how fast the magnesium degrades, so it releases hydrogen more slowly, the body would take up the hydrogen the way it would take up any other gas, and release it."

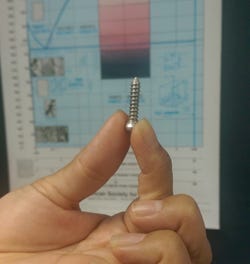

In lab tests, Manuel has been comparing the magnesium pin alongside other clinical implant materials to see how it stacks up in terms of durability. Surgical pins are shaped like screws, which means the magnesium pin needs to be able to withstand minimal amounts of torque without stripping the screw.

Manuel hopes that continued research can lead to clinical trials before eventually landing on the technology market. As part of their research, Manuel and her team continue to observe the potential impact of their prototype. "People who have sensitivity to metal or inflammation from foreign material in the body could benefit from this," she said. "There are a lot of different applications that could be possible."

While the benefits and applications continue to be researched, one thing remains clear. Biodegradable implants are no longer a figment of science fiction, they're here to stay. Or at least, they're here to stay as long as they're designed to.

Related articles

Magnesium Alloys Perform Disappearing Act in the Knee

MIT Researchers Engineer a Bone Growth Breakthrough

How Silk and Nanotech Are Driving Ortho Advances

Refresh your medical device industry knowledge at MEDevice San Diego, September 10-11, 2014. |

Kristopher Sturgis is a contributor to Qmed and MPMN.

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to our daily e-newsletter.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like