Releasing People From Prison Is Easier Said Than Done

As the pandemic threatens the lives of those behind bars, the country must confront a system that has never had rehabilitation as its priority.

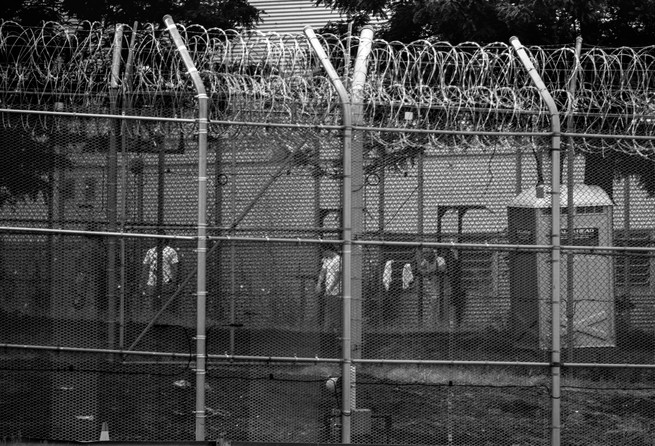

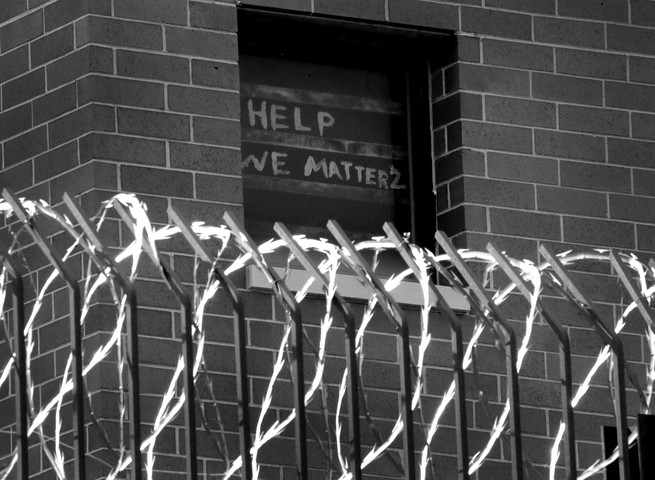

If the coronavirus were to design its ideal home, it would build a prison. Inmates are packed together day and night; social distancing, frequent hand-washing, and mask wearing are fantasies. Many inmates are old, sick, and prone to infection. Most prisons are operating near capacity; some house more prisoners than they were built for. The five largest clusters of the virus are in prisons; in Marion County, Ohio, 95 percent of inmates tested positive.

The stark and irrefutable images of police officers killing Black men and women for small infractions have sparked protests and a larger rethinking of how America treats people who cross paths with the criminal-justice system. Even before the killing of George Floyd, the public and politicians had grown troubled by a less visible but still shocking death toll behind bars, where inmates are trapped as the virus spreads, effectively turning their prison sentences into death sentences. How do we stem the wave of infections? The answer, according to many advocates, is simple: Release prisoners.

Some governors, alarmed at the deaths in prisons and jails and worried about the risk to surrounding communities, are listening—sort of, with an ear attuned to the political liability. More than half of the states have agreed to release people convicted of low-level crimes, people who are nearing the end of their sentences, or people who merit compassionate release, such as pregnant people or older, vulnerable inmates.

“It’s been helpful. I know that people have gotten out, and I am moved by their release,” says Nicole Porter, the director of advocacy at the Sentencing Project, a research organization that campaigns for sentencing reform. “But none of it has been substantial. And what I hope this moment tells us is that our incarceration rate is a function of politics—because there are many questions about who needs to be incarcerated.”

“We’re barely scraping the surface,” says Abbe Smith, a professor at Georgetown Law School and the author of Guilty People. “Even if we release the low-hanging fruit,” Smith says—what she calls the “non non non”: nonserious, nonviolent, nonsex offenders—“that wouldn’t make a dent.”

To meaningfully reduce America’s prison population and slow the pandemic will require cutting away not just fat but muscle, releasing not just nonviolent drug offenders but those convicted of violent crimes. The difficulty of doing so, in both practical and moral terms, is enormous. Which people convicted of murder or armed robbery do we release? How do we decide? And how do we guarantee that they won’t offend again, especially as they try to restart their life during the worst economic collapse in nearly a century?

In one way, the pandemic has created the perfect justification for releasing people convicted of violent crimes—stopping the virus. But at the same time, it has created the worst possible conditions for their release: They will struggle to find jobs; the organizations devoted to helping them will be strapped for funds; housing and even food may be out of reach. John Pfaff, a law professor at Fordham University and the author of Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration and How to Achieve Real Reform, notes that in this economy, we could see an uptick in crime. “People would say: ‘Bob was released early from jail and he went off and committed this robbery,’” he says. “And the real reason for the robbery is that Bob got released early and there were no jobs; therefore, he committed the robbery. But if you’re a police chief or a [district attorney], it’s very easy to turn the economic-driven crime into criminal-justice-reform-driven crimes.” That is his nightmare, and it’s easy to see why.

advocates say prisons are brimming with candidates who deserve a second chance—men and women who made egregious mistakes when they were young, whose crimes say more about the impulsiveness of youth and the trickiness of navigating inner-city violence than they do about character. Yet in large part, these are not people whom the system has been preparing for release.

Prison can serve many purposes—to deter people from committing crimes in the first place, to punish them if they do, or to rehabilitate them and usher them back to normal life. America has by and large chosen the punitive path, imposing decades-long sentences intended to reduce crime on the streets. During that time, inmates usually don’t receive the kind of training or care that would enable them to return to the outside world and build a new, stable life. This presents a giant hurdle for those who would wish to release prisoners now.

“Prison doesn’t rehabilitate you,” said Angelo Robinson, who served more than 20 years for murder. In many ways, he told me, life in prison is no different from life on the streets. “As far as the drugs, the killing, the fighting, it’s all in prison as well. The guards don’t come in there and try to help change you. No, they come there with their problems as well.” Any propulsion toward redemption comes from within. “You have to want to change your life. And a lot of guys there don’t want to.”

Robinson’s prison story begins around 10 p.m. on February 17, 1997, as he and a few friends were doing business in an apartment in Cincinnati’s West End neighborhood. Robinson, who was 20, was locked in the bedroom, guarding the stash of crack, when he heard the front door burst open, screams, and gunfire moving down the hall toward the bedroom. “I just thought, I’m a dead man,” Robinson recalled. He shot through the bedroom door, and when the apartment fell quiet, he found his friend, Veronica Jackson, dead in the hallway. Not until days later did he learn that it was his bullet that had killed her. “I felt horrible,” he said. “I took someone from her family. She had children. I think about it every single day.”

Prosecutors offered him 14 years if he would agree to plead guilty to manslaughter. Robinson thought he could prove self-defense, and opted for a trial. A jury convicted him of murder and sentenced him to 29 years to life.

Robinson’s is one story in the larger narrative of how America’s inmate population has more than quadrupled since 1981, turning prisons into crowded, unsanitary places just waiting for an infectious disease to arrive. Since the dawn of the tough-on-crime era, people convicted of violent and even some nonviolent crimes have received ever-longer sentences. This is not because Americans have become more savage; in fact, rates of violent crime have fallen by 50 percent since the early 1990s. But even as street violence has been quelled, time served in prison for homicide and non-negligent manslaughter has tripled, and one out of seven inmates will be in prison for life. New offenders arrive and old offenders take years to leave; prison is like a dam with no outlet, and today the reservoir is flooding its banks.

This unforgiving policy has an emotional appeal to voters, perhaps, but defies logic based on statistics. “Why should we lock someone up for 50 years?” Pfaff asks. No other Western country does that, he says, and the social science is “unambiguously clear” that people age into and out of violent behavior. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, homicide arrests peak at age 19; arrests for forcible rape peak at 18. “A 50- or 60-year-old person is just not the violent person that they were when they were 20,” Pfaff says.

These long sentences sprang from a retributive mentality, but they also signal the smartest way to thin the ranks of prisoners during a pandemic: Start with older prisoners. “Every year we keep somebody in prison after 30, and certainly after 40 or 50, we’re getting diminishing returns for public safety,” says Marc Mauer, the executive director of the Sentencing Project. Meanwhile, Mauer says, because of poor health care, aging prisoners are growing sicker and more expensive by the year. “The costs become enormous to prevent less and less crime over time.”

Of course, these numbers don’t account for the social cost of long sentences, the loss of a father or mother or son, the emotional strain, the dismantling of community, the hopelessness that comes when a young man is warehoused in prison for the rest of his life. For several years, Robinson marinated in that loss, until one day he thought, “You can’t just sit here and rot.” He decided to get an education.

Here he smacked into a roadblock to not just personal fulfillment but rehabilitation, which is, in theory at least, a cornerstone of prison. Typically, the classes, apprenticeships, and programming that might prepare an inmate to reenter society are a scarce resource given first to inmates who are within a year of release, according to experts such as Mauer. “And here I was, 29 to life,” Robinson said. “I was the last on the list.” Robinson decided to figure out another way. He snuck into classes and audited them. He managed to earn his GED, whose test is available to most prisoners. He taught himself Spanish and sign language; he learned to read music and play the guitar. He applied himself to his work, learned how to operate a forklift, to upholster furniture, to cook.

The prioritization of inmates close to release penalizes prisoners like Robinson, who have long sentences but the possibility of parole, Mauer says. The parole board considers not just bad behavior but good, not just disciplinary actions but also classes and apprenticeships, which indicate that you want to better yourself. Someone like Robinson would come up short, “not because you don’t care, but because you haven’t had access to programs,” Mauer says. “So they say, ‘You’re denied, because you don’t have a good prison record.’”

But Robinson was, for once, lucky. In 2012, David Singleton, the executive director of the Ohio Justice and Policy Center, represented him in a civil-rights lawsuit, forcing the prison to allow him to receive a needed surgery. “I knew this is somebody I’d love to be my neighbor one day,” Singleton says. Over the next few years, Singleton, who is also a professor at Northern Kentucky University’s Chase College of Law and a former public defender, developed a counterintuitive approach: Persuade the people who put the criminal in prison to advocate for his release. Last year, the Ohio Justice and Policy Center launched Beyond Guilt, a program that works with prosecutors and victims’ families to secure the release of those convicted of more serious crimes, including violent offenses.

“We’re the Guilty Project,” Singleton says, laughing. “We want to represent people who are guilty but who are still human beings and deserve to not be written off.” To be considered, a prisoner must have admitted his guilt, served a significant part of his sentence, and demonstrated evidence of rehabilitation, whether formally, through classes, or reputationally, by mentoring and being a force for good in prison. The project also looks for people who have aged out of crime: those convicted in their teens and early 20s, but who have had a few years for their behavior to mellow.

Robinson became the project’s first client. Singleton approached members of Veronica Jackson’s family about supporting his release, and all but one relative agreed. “He was a young man when this crime happened and he has served long enough,” the victim’s sister, Sarah Jackson, wrote in an affidavit. “It’s time for him to come home to his family.” The victim’s son, Clifford Jackson, had expressed reservations in the past, telling The New York Times in July 2019: “We were never compensated for anything. We’re only compensated by his time.” He could not be reached for comment for this story. Steve Tolbert, the chief assistant prosecutor for Hamilton County, Ohio, joined Singleton to petition the court for Robinson’s release. “Morally, it just feels right,” Tolbert told me. “This person made a huge mistake, and we’re willing to take that chance in these limited circumstances.” On August 1, 2019, Robinson pleaded guilty to manslaughter and walked out of prison. He had spent 22 years, more than half his life, behind bars, but at 43, he hoped to spend the rest of his life free.

Last year, 15 people convicted of violent crimes—including three convicted of murder—were freed thanks to Beyond Guilt. Singleton says they are all “adjusting well to the ups and downs of life”—no small thing during a recession and a pandemic. But the story is as daunting as it is encouraging. Unless governors unilaterally release large numbers of people—an extremely unlikely prospect—these inmates will be the rarest of exceptions. How many prosecutors are willing to petition a court for the release of a criminal convicted of violence? How many victims’ families will support the freedom of a man who raped or killed or beat their sister? How many other legal organizations have the money or staff to fight this painstaking, time-consuming battle? As far as I can tell: close to zero. Last year, Beyond Guilt reduced Ohio’s 49,000-person prison population by 0.0003 percent. It’s like trying to empty the ocean with a teaspoon.

for those who do make it out, building a stable life could seem all but impossible during the pandemic. It was already hard enough in normal times. Michelle Robinson knows this well.

On the night of April 4, 2007, Robinson (no relation to Angelo) allowed two male acquaintances into her apartment so that they could rob her friend, William Means, who was spending the evening there. Means had a job and money, and during the robbery, one of the men drew a gun and shot Means to death. The prosecutor offered Robinson 10 years if she pleaded guilty to manslaughter and robbery, but on advice of her attorney, she turned it down. She was sentenced to 18 years to life. In prison, she rose to the status of an “honor lifer,” running classes for other inmates, and earning certificates in janitorial and electrical work. In 2019, Singleton and Tolbert, the prosecutor, persuaded a court to let her accept the plea she had rejected a decade earlier, and free her with time served.

The return to civilian life, particularly for those who have spent a decade or more in prison, can be a disorienting, uphill climb. Finding an apartment, landing a job, applying for a driver’s license, paying off debts such as child-support payments when you’ve been earning 40 cents an hour—all of these make the transition a Sisyphean task. State and local governments have no obligation to help a prisoner reenter society. “They don’t have to do a thing,” Mauer notes, “and in most cases, they do a very inadequate job.”

Some cities, such as New York, offer a range of programs—job training and placement, affordable housing, drug-treatment programs—often by funding nonprofit community or religious organizations. But if you’re unlucky enough to be from, say, rural Alabama or Mississippi—almost any rural community, in fact—you’re pretty much on your own.

The pandemic exacerbates the problem. Could these organizations, already operating on goodwill and a shoestring, handle hundreds or thousands of people released at once? “That would stretch [them] to the limits,” Singleton says.

“Every single state is going to go through a financial crisis,” says Arthur Rizer, the director of Criminal Justice and Civil Liberties at the R Street Institute, a center-right think tank. “Where are they going to cut their money? It’s not going to be from Main Street. It’s definitely not going to be Wall Street. It’s going to be from the services that provide the types of things that these people need to come back to the fold.”

Last summer, when Michelle Robinson left prison, the marketplace was ravenous for labor, and her reentry proceeded relatively smoothly. She moved in with her daughter, and landed a job with a company that cleaned up houses damaged by floods, fires, and other natural disasters. “I had a good job ’til this COVID-19 started,” she says. She was laid off in March, when the state locked down and the company’s contracts disappeared. She would fire up the computer three or four times a day and apply for every job she could find, reluctantly checking the box inquiring about felony convictions. She rarely heard back. “Tyson Foods hires felons, but they’re at their max. Servpro hires felons, but they’re at their max.” So does Kroger, but her conviction is “too fresh.” She can’t work at drive-throughs: “With a robbery on there, they don’t want me counting money.” After three months, she finally landed a job at a restaurant.

Prisoners released today will face a market with more than 11 percent unemployment. They will compete with people with clean records, and depending on how long they’ve been incarcerated, they won’t possess the technological skills expected in a modern workplace. They’re at a serious disadvantage. Except for this: They’re desperate. “The people we get out of prison will be willing to do the frontline jobs where they’re at risk,” Singleton says. “It’s almost like they can’t be at more risk than they are in prison.”

those are the practical challenges. The moral question—who deserves to be released?—is even more daunting. Is the inmate truly penitent, or merely saying the right words? Has he matured past his violent tendencies, or is he a tinderbox waiting to ignite once he’s out? Does the family of the victim agree, or will his release only add to their pain? Is the crime simply so heinous that even a perfect record cannot overcome it?

Consider the case of Nathaniel Jackson, who happens to be a relative of Veronica, Sarah, and Clifford. (Singleton learned of Nathaniel Jackson’s case when he worked to help free Angelo Robinson. When Jackson's family saw how Singleton helped secure Robinson's release, they asked him to look into Nathaniel's case.) In October 1990, Jackson, a 26-year-old drug dealer in Cincinnati, came to believe that a man named James Foster had stolen cocaine from him. Jackson and his associates snatched Foster, doused him with gasoline, and set him on fire. The young man survived, with burns on more than 70 percent of his body. Jackson and his friends were charged with attempted murder, but four days before trial, they had Foster killed. Jackson was later convicted of aggravated murder and sentenced to 23 years to life.

Jackson has now spent 28 years in prison, and where some see a callous murderer, others see a man transformed. “His mission in life now is to get out and keep young people from making his mistakes,” Singleton says. “He’s a good man now. He did bad shit before. But he’s totally changed.”

Singleton believes that Jackson deserves a second chance. But there are few exits for prisoners serving long sentences for violent crimes. There are no laws that invite judges to reconsider long sentences: Bills that would do so, called “second-look acts,” have been introduced in 18 states and the Senate, but none has passed. Most prisoners eventually come up for parole, but experts say parole is usually denied year after year, often because of the seriousness of the crime, which of course will never change. Jackson, for example, was denied parole in November. Governors sometimes pardon inmates, but they are disinclined to show mercy toward men like Jackson, even if they no longer pose a danger to society. Even with the threat of a deadly virus, so far governors have drawn the line at violence. “Governors are making a very calculating decision that it’s probably better for them politically for 10 men to preventively die in prison from COVID than for one of them to do something wrong if he’s released early,” says Fordham’s John Pfaff. “We don’t view these deaths as all that problematic.”

Jackson is so far Singleton’s riskiest proposition. But the lawyer believes that Jackson’s prison record proves he’s worth the risk. He has been moved to a minimum-security facility. According to guards, staff, and volunteers who work with him, Jackson is a “model inmate,” a mentor for younger men, a “spiritual role model” because of his strong Christian faith; his “exuberance and zeal for recovery has been infectious.” He received top ratings for his behavior in prison and on the job, as a forklift operator and an upholsterer. “I am still working on myself,” he wrote me in an email. “I am truly an asset to the community which I am in now, but truly want to do a much better job once Mr. David helps me get released.”

Singleton recently sent a petition to Steve Tolbert. While Tolbert has proved amenable to petitions in the past, he wishes the Jackson case would just go away. “If we were to go along with this, this would be the toughest call we’ve ever made,” Tolbert told me. “I mean, he set a guy on fire.” Then he had the victim killed. Tolbert hasn’t decided yet, but “I would not go to the local casino tonight and bet on this one happening.”

“Maybe he has reformed,” observes Donna Foster, the victim’s mother, “but I wish he had reformed before he killed my son.” She says she won’t block his release, but won’t support it either. Still, she’s puzzled: Why free Nathaniel Jackson? Why does he deserve a second chance? “My son will never be able to walk the streets again,” she says. “I will never have any grandkids by my son. I will never go to his wedding. It’s over.”

Perhaps Jackson is a new man; perhaps he has paid his debt in full. But is this the risk that prosecutors and judges want to take? Is this a person who has earned the forgiveness of his victim’s mother and siblings? Even if Jackson no longer poses a danger, can society forget that murder, so breathtaking in its violence? Even during a pandemic, Jackson is a hard case, but it’s likely that if we start considering large releases of people convicted of violence, there will be far more hard cases than easy ones.

the pandemic is inducing governments to engage in some complicated accounting: compassion and the prospect of redemption on one side of the ledger, retribution and the risk of unleashing new violence into the community on the other. One bad case could torpedo all the progress, Tolbert worries. “The future of this [Beyond Guilt] program depends upon every one of these people,” he said. If a prisoner gets out Friday and assaults someone on Saturday, there would be two casualties: the victim of the crime, and the prison-reform movement. If a prisoner released through Beyond Guilt makes a violent mistake, “this whole program is going to look really, really bad and the plug is going to get pulled.”

That question—what if it backfires?—keeps prison-reform advocates like Arthur Rizer at the R Street Institute staring at the ceiling in the middle of the night. “I already feel it in my bones—the next wave of the Willie Horton ads,” Rizer says. In 1986, Horton, who had been convicted of murder, was allowed a weekend out of prison as part of a Massachusetts furlough program. He fled, raped a woman, and knifed her fiancé, before being captured. Aside from sinking the presidential hopes of Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis in 1988, the Horton fiasco prompted furlough programs to be canceled across the country. “So what happens when one person is a COVID release and then they commit a brutal, horrible crime?” Rizer asks. “You’re going to have people run, run their campaigns on: We need to put more people in prison.”

But what if this radical idea works? What if Angelo Robinson builds a career, has a family, pays taxes? The man who once committed a homicide now works as a machinist at Meyer Tool. He’s been promoted after less than a year, and the company is paying his tuition at Cincinnati State, where he’s earning a software-engineering degree. At night, Robinson works construction, remodeling houses. He sees his daughter every week, and he’s saved enough money to get a mortgage and start looking for a home to buy. “I’m ecstatic,” he told me. “When I wake up in the morning, I say to myself, It’s a new life for me.”

Robinson’s story is, so far, a happy one. But if the country is to chip away at prison overcrowding, if the country wants to stave off the next wave of COVID-19 sweeping through prisons, or the next infectious disease, or the next, his story will have to be repeated not 10 or 20 times, but thousands of times.

This article is part of our project “The Presence of Justice,” which is supported by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge.