Folks, Edgar Wright does a lot of things. Direct the British sitcom Spaced, for example. Burst, blood-covered, into feature filmmaking with Shaun of the Dead, for another. Crossover between multiple genres while combining distinctive soundtracks, eye-blurring editing, and a whip-crack comedic timing to form a distinctive style, for a third. But what Edgar Wright does not do, in my humblest opinion, is miss. We here at Collider dot com rank the filmographies of our favorite filmmakers—like David Fincher, James Wan, and Guillermo del Toro, for example—because we were all born with the incurable medical defect known as being Extremely Online. It is what it is, and it's also what's happening here. I put the numbers next to the titles and will maybe mention a little more negatives toward the top, but I don't think Edgar Wright has made a "bad" film yet. If you disagree, so it goes, please report to the comment section. But what follows is less of an argument and more of a chance to dissect the unique ebbs and flows of one filmmaker across 16 years.

One more thing, though, to be clear: Wright technically began his feature career with 1995's A Fistful of Fingers, a film I have never seen and, judging by its general obliteration from existence, Edgar Wright doesn't really want me or anyone else to see. It's a 78-minute Western shot for $15,000 that never found a distributor. I think it'd be chill if we all quietly agreed it'd rank last and move on. Should Wright decide to release A Fistful of Fingers at any point and it does, in fact, whip ass, I will rectify this decision posthaste.

With that said, here are all the films of Edgar Wright, ranked.

8) 'Don't!'

Sure, Don't! is just a one-minute-and-36-second long mock-trailer that debuted in Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez's double-feature Grindhouse. But it's also a goddamn delight, and if you're thinking of complaining about its presence on this list....

Don't.

7) Baby Driver

Track number 5 with a Bullitt. Despite a bevy of stylized car chases, a soundtrack that perfectly matches the fits and starts of automatic gunfire, and a Jon Hamm that continues to defy the laws of human aging, Baby Driver feels like Wright's most grounded film. Whereas the filmmaker had mostly dabbled in straight-up action-comedies to this point, Wright described his latest as an "action-thriller that is funny throughout." That sounds like splitting hairs but Baby Driver does feel mostly like Wright getting the chance to act out set-pieces that've been playing out in his head for years. (Which is, apparently, true.) The action in Baby Driver, coordinated largely in tandem by second-unit director Darrin Prescottand stunt driver Jeremy Fry—then captured with oil-slick coolness by DP Bill Pope—comes with the joy of a kid making vroom-vroom noises on the carpet. There's a sort of beautiful lightness to it that makes a heist getaway feel like a musical number,

That's not to say Baby Driver isn't full of simple charms. Wright remains the only director to make Ansel Elgort likable, and it's not my place to say whether that's because Baby barely speaks. As the tinnitus-afflicted getaway driver with headphones permanently attached to his ears, Elgort glides through the film, as if Baby can only comprehend movement if it's on four wheels. The movie is twee as hell, but the sort of Old Hollywood sentimentality Wright puts into everything smooths it out. It's not enough for two young lovers to share an AirPod in a laundromat, but the spin cycles behind them will blend into a colorful, carefully coordinated tableau.

Where Baby Driver fails just a bit more than Wright's previous films is on a script level. Lily James is wasted as waitress Debora, whose main purpose is mostly to wait around for Baby to stop fucking up. Everything in this movie is laser-focused on getting visuals into place, and occasionally characters like Debora—or Jamie Foxx, magnetic as always as the tattooed psycho Bats—feel like plot placeholders more than people. Unfortunately, it also only took three years for the ending to feel a little ehhhh; this idea of a baby-faced white dude getting peacefully taken in and eventually released early for being a Good Egg.

I also cannot stress enough how hard the soundtrack rips. Don't hit play on "Bellbottoms" unless you're willing to get a speeding ticket. Combining the soundtracks to Baby Driver and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood should be illegal in all 50 states.

6) The Sparks Brothers

The Sparks Brothers is a love letter in every sense of the word. With the help of some notable names in music, film, literature, and more, Wright charts the consistently weird career of the pop-rock band Sparks—namely, brothers Ron and Russell Mael—over the course of fifty years and 25 albums, all of it spent just a few levels below mainstream popularity. The Sparks Brothers is absolutely a documentary that'd be recommended by Stefon, because it does, in fact, have everything: animation, stop-motion, stock footage, interviews with everyone from Flea to Neil Gaiman. A documentary this committed to visual and thematic zaniness probably wouldn't work if it was covering anyone but Sparks, but thanks to the Mael brothers' decades-long commitment to oddity, the doc's aesthetic ADHD actually enhances its core themes. Across its two-hour-plus runtime, The Sparks Brothers never really stops being an ode to creative integrity; Sparks spent a long, long time—from their 1971 self-titled album to this year's gonzo Leos Carax movie musical Annette—being wholly themselves, public approval be damned.

Unfortunately, that impressive consistency is also the movie's narrative downfall. Or, I should say, there isn't much of a narrative at all. The Sparks Brothers is entirely a celebration, an appreciation of a perennially underappreciated pair of artists, and while that makes it a joyous experience, it doesn't actually offer much insight. You learn that Ron and Russell Mael are two lovely, strange fellows who made lovely, strange music for 50 years. Ron himself, describing the duo's throw-everything-at-the-wall creative process deep into the doc, also incidentally sums the film's one flaw: "We do quite a bit of foolish things, but you'll never hear about them."

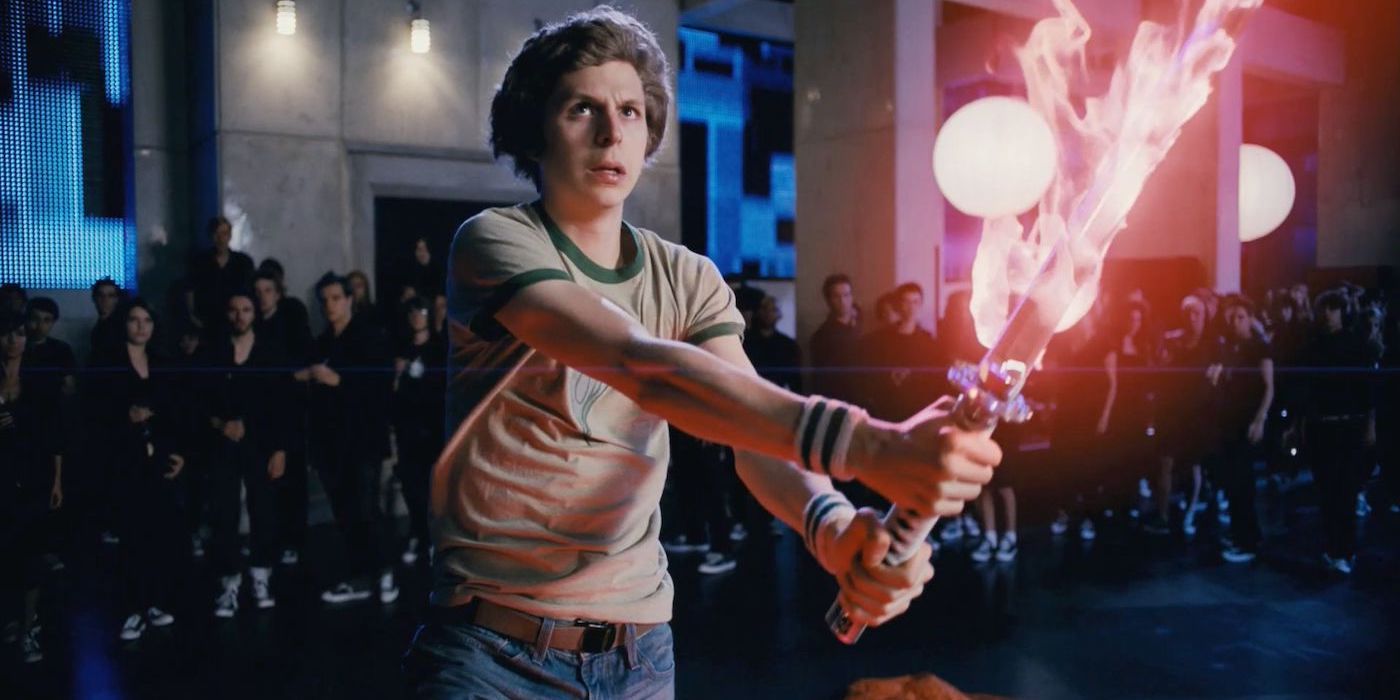

5) Scott Pilgrim vs. the World

Scott Pilgrim vs. the World is a whole lot. Wright's only adaptation (RIP Ant-Man). His first collaboration with Pope, who shot both The Matrix and Clueless because legends have layers. A near gag-a-minute comic book movie framed like a video game that established Wright's singular style on a canvas larger than Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz combined. It was also a pretty huge box office bomb, notching just $48 million on an $85 million budget. Marketing didn't help, but there's also something to be said about audiences expecting Michael Cera comedy and getting Scott Pilgrim's...much-ness. There's something distinctly not-American about how little the movie cares for explaining itself. Here's Wright himself on the go-for-broke tone, which borrows from Italian films like Mario Bava'sDanger: Diabolik.

"[Scott Pilgrim has an] Italian influence, a sense of completely unbridled imagination. They don't make any attempt to make it look realistic. Mario Bava's composition and staging has a real try-anything attitude."

In Scott Pilgrim, Wright really does try anything, and the result is a whirlwind of color and choreography that'll plop a Bollywood number in the middle of a wire-fu fight. Cera stars in the title role, a skittish bass player who cruelly dumps his high-schooler girlfriend Knives Chau (Ellen Wong) in favor of the too-cool Ramona Flowers (Mary Elizabeth Winstead), not knowing that to win Ramona's heart he has to battle her Seven Evil Ex-Boyfriends. Wright pulls off a mighty impressive juggling act, because at the core of the storm is a simple bit of reliability. It's a story about the ways positioning your personal shit as the main quest can blind someone to the perfectly playable narratives around you.

But also, it just whips complete ass. Scott Pilgrim isn't Wright's best movie but it is his best action, which is easy to forget because of how dang funny it is. These are tussles put together by Penz Zhang, a member of the Jackie Chan Stunt Team—the premiere players for getting kicked in the face—and captured by Bill "Did I Already Mention The Matrix?" Pope. You almost don't need the VFX bells and whistles to have lightning flashing across the screen.

Scott Pilgrim also enjoys one of the best ensembles in the last decade; a crew of familiar faces, most of them just on the brink of superstardom who are all in on Wright's rapid-fire shenanigans. With all due respect to the literal concept of America, Chris Evans has never been better than as action-hero extreme sports enthusiast Lucas Lee. (The star of such films as You Just Don't Exist and Action Doctor). Aubrey Plaza debuted her potent lack of fucks to a world not caught up on Parks & Recreation quite yet. I think about Clifton Collins Jr. and Thomas Jane's one minute of screen-time as the Vegan Police at least once a month. The list just goes on—Brie Larson! Brandon Routh! Kieran Culkin!—and not a single person misses.

Really, Scott Pilgrim's only major failing is in its excess. It has all the breathing room of a House of the Dead booth. But paired with, say, Baby Driver, you can see Wright's determination to form something with this frenetic energy around a story that lands every beat flawlessly.

4) Last Night In Soho

After making his first major bite mark on Hollywood with Shaun of the Dead, it took another 17 years for Wright to craft an out-and-out horror film, and man oh man can you feel the weight of those in-between years across Last Night in Soho. This is the filmmaker's darkest, most mature film by a wide margin, clearly inspired by blood-soaked Giallos and cerebral 1970s horrors like Don't Look Now. Where once he was busting out every trick in his arsenal in service of zaniness, to create a sort of dream logic, here Wright wants to pull you down into a nightmare. You're never properly oriented in time throughout Last Night In Soho, much like social outcast and budding fashion designer Eloise (Thomasin McKenzie) feels unmoored in her own present as she's repeatedly pulled into the past to learn the tragic tale of lounge singer Sandie (Anya Taylor-Joy).

Which isn't to say the movie isn't still dazzling. Wright purposely puts a drab, grey-ish layer over present-day London so that when Eloise travels back to the swinging 60s, it pops. The intense golds and deep reds of the marquees puts you in Eloise's shoes while, of course, blinding both her and us to the darker underbelly those neon lights obscure. Together with cinematographer Chung-hoon Chung (IT, Oldboy), Wright pulls off arguably the most impressive camera-work of his career, McKenzie and Taylor-Joy swapping spots in between moves on the dance floor or sharing a reflection in mirrors that extend off into infinity in Citizen Kane-esque fashion.

It almost makes sense in a film this occupied with disorientation that Wright and co-writer Krysty Wilson-Cairns (1917) get a bit lost themselves. Last Night In Soho effectively builds an intriguing mystery that spans decades but, without overtly spoiling, heads to a twist that muddies the movie's own message. (It does earn major points for giving the great Diana Rigg one hell of a final performance.) What saves it, though, are McKenzie and Taylor-Joy, both astounding from frame one. McKenzie can play out an entire arc, from timid to empowered to terrified at the sudden change, with her eyes, while Taylor-Joy is the human embodiment of stage makeup hiding human scars. Also worth noting that it feels unfair, on a cosmic level, that Anya Taylor-Joy is able to sing as beautifully as she does.

3) Hot Fuzz

Just two movies into his post-Spaced film career, Wright decided to fuck around and make one of the best buddy action-comedies of all time. Of the three Cornetto movies, Hot Fuzz has the least depth, but it's the most rewatchable because holy hell is it a pure blast-and-a-half. While it doesn't dive too much into the human condition, it bores a hole deep into genre tropes—not just action films, but also classic slashers—creating the type of "parody" that could only come from someone who loves the tools he's wielding. In that sense, it's aggressively Wright's sophomore feature, because after establishing yourself all ya wanna do is start showing off.

Hot Fuzz stars Simon Pegg—who co-wrote the script with Wright, as he did with Shaun of the Dead and would do with The World's End—as ambitious, uber-competent police officer Nicholas Angel, assigned to the impossibly quaint town of Sandford,Gloucestershire. Saddled with a bonehead partner, Danny Butterman (Nick Frost), Angel attends to traffic matters and escaped swans until a masked madman starts to commit gruesome murders disguised as accidents.

The key to a successful parody is keeping a straight face while beating the tropes as hard as you can, and Wright pounds those things like a drum. He and Pegg watched, in their words, "like 138" buddy-cop movies in the writing process, and the finished product leaves no stone unturned. The macho attitude, the gun fetishism, the untold amount of property damage swept under the rug. The genius of setting Hot Fuzz in a rural haven is the ability to take these Big Badass signifiers and make them small, analyzing them at their base level. The climactic car chase rips in the same way, say, Bad Boys rips, but we're dodging swans instead of Ferraris. (Timothy Dalton's terrified "swan!" plays on a loop in my head 24/7 and I refuse to seek medical attention.)Wright's love for Italian filmmaking pops back up in Hot Fuzz's violence, too. There's more than a touch of Giallo to the murder sequences, where the comical amount of blood is the point.

Again, as in the case of Scott Pilgrim, you could talk for hours about the technical aspects of the action and forget the film is just damn funny. The script is Wright and Pegg in full, endlessly quotable form, but the film is also brimming with visual comedy. Hot Fuzz is Wright's live-action Simpsons episode, taking two hours to fill Sandford with memorable side-characters—David Bradley's gun-hoarding hermit is a highlight—and sight gags. I'd gladly buy a framed portrait of Dalton standing in front of his own framed photo, then I would pay obscene amounts of money for Dalton to stand in front of that.

Wright would have more to say both before and after Hot Fuzz, but he never gave himself quite this much to pull off. Anecdotally, this is many people's favorite Wright film, and it's tough to argue against something this criminally entertaining.

2) The World's End

If Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz are the frosty first sip of a fresh-poured pint, then The World's End goes down like the very last swallow, bitter but necessary if you want to move on. It's the least warmly received of the Cornetto Trilogy, but that's because it's the least warm, period. Truth be told, it's a fucking bummer, a very specific type of nostalgia-tinged gut-punch that literally every human on this Earth beholden to the passage of time can relate to. (Congrats, I suppose, to Paul Rudd.) But it's also wildly hilarious, deeply cathartic, and beautifully sloppy, all in the way a drunken night of truth-telling can be as good for the soul as it is bad for the head.

When you hear how The World's End came to be, you understand it couldn't have been any other kind of movie. Wright wrote a script called Crawl at 21, before Spaced was even a thing, chronicling a pub crawl, a.k.a the most interesting thing possible to a 21-year-old. He revisited the script decades later, pushing 40 and coming off of Scott Pilgrim. The World's End is a movie not only about revisiting, but the ways we change in the interim. Along with co-writer Pegg, he added a heaping dose of body-snatching sci-fi to the script's bare-bones, trying to capture "the bittersweet feeling of returning to your home town and feeling like a stranger."

Pegg stars again as Gary King, a former high school legend turned 40-year-old alcoholic, who rounds up his buddies—Andy (Nick Frost), Oliver (Martin Freeman), Peter (Eddie Marsan), and Steven (Paddy Considine)—to complete their hometown pub crawl, the 12-stop "Golden Mile", one last time. Unfortunately, the gang has matured, and the old town, well, the old town has been taken over by body-swapping aliens. Bon Jovi, as it turns out, is completely full of shit.

Part of the appeal and the push-back is how hard Pegg and Frost are both playing against their norms. As Gary King, Pegg's performance is unpleasant but not in the loveable-loser sense; it's more like the way a man can cling to his past like a drown victim trying to not get swept upstream. For Gary, completing the Golden Mile is less a night out with the lads as it is an attempt to say he completed something in his life. Pegg pulls this off with increasingly manic energy, desperation that fits equally in an alien invasion and nervous breakdown. As usual, Frost is Pegg's foil but in reverse. Andy, thanks to a drunken car crash, has given up drinking, and Frost flourishes in his chance to play straight man.

The placement of The World's End in Wright's filmography is fascinating, not only as the unofficial end to the Cornetto Trilogy but also side-by-side with his contentious Ant-Man experience and pivot to a completely original dream project, Baby Driver. It's not like Wright isn't having any fun here. The sci-fi side of the story—captured with gorgeously garish B-movie sensibilities by, who else, Bill Pope—is still a blast. (Gotdamn Bilbo Baggins gets his head knocked off with a bar stool.) But it's inarguably Wright's most mature movie [UPDATE: Well, it was, until Last Night In Soho], a farewell and a reaffirmation at the same time.

And, okay, not to sound like a broken record but in addition to all of the above, it's still, against all odds, just really, really funny. There's a gag with Nick Frost putting his hand through a glass door that straight up puts me on the floor every single time.

1) Shaun of the Dead

Your mileage may vary, but the reasoning here is simple: The horror-comedy is my favorite genre, and Shaun of the Dead is the greatest horror-comedy of all time. The concept is so simple it's undoubtedly been pitched across an immeasurable number of pot-filled dorm rooms since the dawn of man: A zombie film that follows the expendable background characters, the perfectly unheroic everyman who wouldn't notice the world had even ended until about three beers into happy hour. In Wright's hands it's a modern classic, a love letter to a lumbering genre, and a kick-in-the-ass to start living while your body's still warm.

I've said it before and I'll say it again: Thank God for Resident Evil. The inspiration for Shaun of the Dead came during a 5 AM milk run following an RE all-nighter; Wright emerged bleary-eyed into a still-slumbering city and wondered, "What would a British person do if zombies appeared now?" Like most promising first-time filmmakers, Wright had a hell of a hook and a whole lot of favors to call in. A large portion of the film's zombie extras were Spaced fans responding to an open call. They all earned a pound, mostly standing around for hours on end, as extras so often do. "When we eventually involved them properly, they had this electric energy: a pure, crazed hysteria," Wright wrote.

Luckily, he also had Pegg, co-writer and core of the film as Shaun, the aimless electronic salesmen desperately trying to lead a group of survivors—including his ex-girlfriend Liz (Kate Ashfield), best friend Ed (Nick Frost), and mother Barbara (Penelope Wilton)—to safety. One of Pegg's greatest strengths is embodying unspectacular men who really are trying, bless them. It's why his Get to the Winchester plan is the film's best bit. Pegg sells the sheer confidence Shaun has in this objectively terrible idea. It's also a microcosm of Shaun's entire arc. It takes the literal end of the world to push him past the path of absolute minimum effort.

It's maybe a little ironic to expend this much energy praising a filmmaker's work only to arrive at the conclusion that he peaked with his first movie. But I don't think Shaun of the Dead is the best because it's a "peak", I just love how it masterfully juggles all the themes that would come to define everything afterward. A genre-comedy that pays equal respect to the genre and the comedy. The heightening of an everyday scenario to illustrate how a character going through great internal struggle perceives the outside world. An ending that prioritizes personal connections above a zombie apocalypse (or alien invasion, cult murder spree, bank heist, etc etc.) Shaun of the Dead brought the idea of an Edgar Wright Film to life. That's ironic.

At the end of the day, if the most lasting image of your career is a bloodied band of survivors beating a zombie with pool cues in tune with a Queen song, you did something right, and Wright did it the first time. How's that for a fried slice of gold?