Abstract and Introduction

The effect of tools and methods designed to enhance medication adherence that have been evaluated in randomized controlled trials was studied.

A literature search was performed with MEDLINE, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, PsychLIT, ERIC, and EMBASE for the period from 1966 to December 2000. Only randomized, controlled trials with at least 10 subjects per intervention group were included.

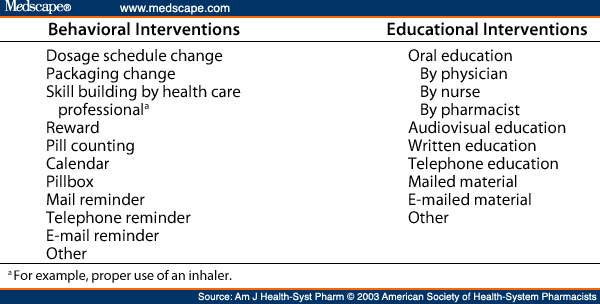

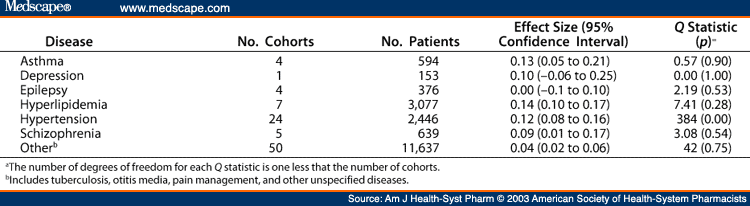

Of 484 articles evaluated, only 61 met the criteria for the meta-analysis. Multiple interventions or study samples were identified in 23 of the articles. Each intervention was counted as a separate study, yielding 95 cohorts totaling 18,922 subjects. Of these subjects, 9,604 (51%) received interventions and 9,318 served as controls. Cohorts reported between 1990 and 1999 accounted for 53% of the sample; 56% of all cohorts were based in physician offices and 26% involved hypertensive patients. Behavioral interventions accounted for 41 cohorts (8,885 subjects), educational interventions for 22 cohorts (6,392 subjects), and combined interventions for 32 cohorts (3,645 subjects). Homogeneity of groupings and effect sizes (ESs) were calculated for each type of intervention. Overall, the data were not homogeneous, so conclusions could not be derived from the entire body of data. The educational intervention and combined intervention cohorts were nonhomogeneous (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01, respectively); however, the behavioral intervention cohort was homogeneous (Q = 42.48, d.f. = 40, p = 0.36). The overall ES for behavioral interventions was 0.07 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.04-0.09). There were no significant differences among the behavioral interventions. Educational interventions had an overall ES of 0.11 (95% CI = 0.06-0.15); there were no significant differences among the educational interventions. The overall ES of the combined interventions was 0.08 (95% CI = 0.04-0.12). When stratifying the combined intervention group by type of behavioral intervention, mail reminders had the largest impact (ES = 0.38).

Meta-analysis of studies of interventions to improve medication adherence revealed an increase in adherence of 4-11%. No single strategy appeared to be best.

Medication nonadherence poses a major threat to the health and well-being of the U.S. population and is financially very costly. It is estimated that nonadherence to prescribed medications causes nearly 125,000 deaths per year.[1] Ten percent of hospital and 23% of nursing-home admissions are linked to nonadherence.[2] A third of all prescriptions are never filled, and over half of prescriptions that are filled are associated with incorrect administration. Nonadherence directly costs the U.S. health care system $100 billion annually. Annual indirect costs exceed $1.5 billion in lost patient earnings and $50 billion in lost productivity.

Medication adherence may be defined as "the extent to which a person's behavior (in terms of taking medications, following diets, or executing lifestyle changes) coincides with medical or health advice."[3] The term "adherence" assumes a collaboration between the patient and the health care provider regarding the patient's health care and health-related decisions. Although "adherence" is generally recognized in the medical community, "compliance" has more frequently been used. Patient compliance is not synonymous with adherence. Compliance may suggest a passive approach to health care on the part of the patient. This paternalistic view of the patient may not encourage the patient to take an active role in his or her health care and may limit the responsibility the health care practitioner accepts for a less than optimal outcome.

Interventions used to improve medication adherence vary greatly. One-on-one oral intervention, with or without written supplementation, is common. However, group-, videotape-, and audiotape-based interventions have also been used. These educational interventions appear to have a favorable impact on adherence.[4] Behavioral strategies, such as reminder notes and special medication containers (e.g., blister packs), also have resulted in improved adherence. Lastly, a combination of behavioral and educational strategies may be effective.

In 1996, Haynes et al.[5] conducted a systematic review of randomized trials of interventions aimed at measuring patient compliance with prescription drugs. The authors screened 1553 citations and abstracts, reviewed 252 full-text articles, and selected 15 randomized controlled trials for study. Less than half of the interventions studied (7 of 15) resulted in significant increases in adherence rates, and only 6 led to better treatment outcomes. The authors noted that some of the interventions were complex and that the treatment effects seen were probably not due solely to medication adherence.

Roter and colleagues[6] conducted a meta-analysis of 136 compliancerelated articles published from 1979 to 1994. The study included interventions that enhanced medication adherence, as well as compliance with appointments. The findings suggested that no single approach is better than another at improving compliance; rather, a combination of approaches appeared to be best. However, this meta-analysis used a definition of patient compliance to include compliance with a broad range of therapeutic recommendations, including appointment keeping and outcomes of dental procedures. Also, the data included results of large, nonrandomized trials that may have overestimated the impact of the intervention.[7]

We conducted a comprehensive review of the literature to identify tools and methods intended to enhance medication adherence that have been evaluated in randomized controlled trials. We used meta-analysis to determine the net and individual effects of those tools and methods and identified apparent gaps in adherence research.

Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003;60(7) © 2003 American Society of Health-System Pharmacists

Cite this: Meta-Analysis of Trials of Interventions to Improve Medication Adherence - Medscape - Apr 01, 2003.