Results

Major Documented Events

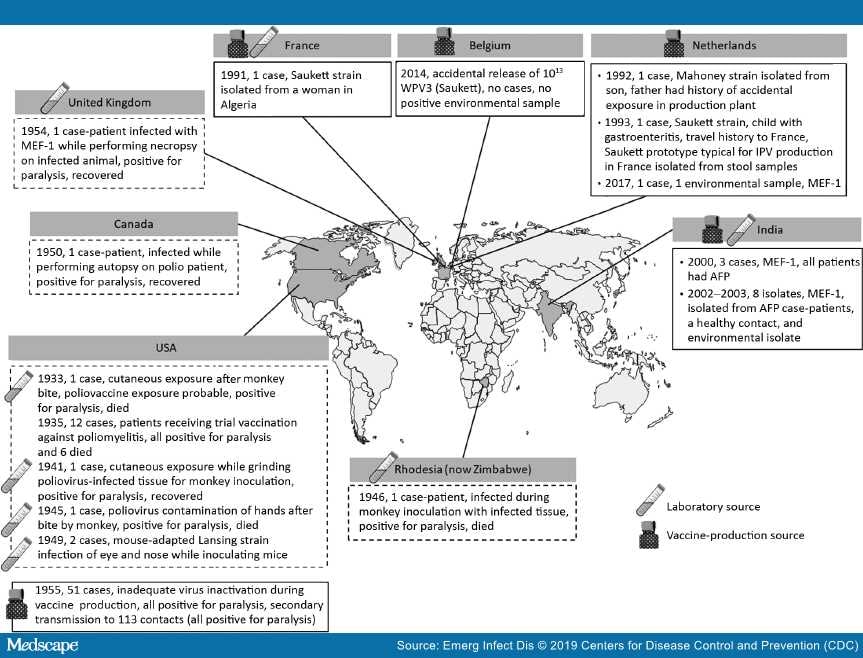

Facility-associated release of polioviruses resulting from either laboratory or vaccine production sources was not uncommon in the period before the development and widespread use of poliovirus vaccines[14–20] (Table 1, Table 2; Figure). In 1933, a 29-year-old physician conducting experimental work on poliomyelitis was bitten by a macaque monkey. Although the exposure to poliovirus could not be confirmed, the physician later experienced paralysis and died.[20,21] The first case of known exposure to poliovirus in a laboratory setting was reported in 1941 in a technician handling infected tissues in preparation for inoculation into monkeys.[19,20,23] Six additional laboratory-associated releases of poliovirus through an infected worker occurred during the same decade: 3 in the United States, of which 2 involved a worker infected with Lansing (Armstrong) strain virus;[18–20,24,36] and 1 each in Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia),[20,37] Canada,[20,25] and the United Kingdom.[20,26] Cases of poliomyelitis attributable to clinical trial use of vaccines or faulty production have also been reported. In 1935, twelve cases of paralytic poliomyelitis, of which 6 were fatal, were reported among those receiving trial vaccinations against poliomyelitis.[22] In 1955, distribution of 120,000 doses of IPV that had been inadequately inactivated during the production step resulted in the paralysis of 51 children, 5 of whom died; secondary transmission was reported among 113 contacts who experienced paralysis, 5 of whom died.[27,28] Although the 1955 incident was inherently distinct from all other examples discussed in this review (with the root cause being faulty production procedure instead of accidental release or exposure), we include it in this report for completeness. The number of subclinical infections with poliovirus during this period is unknown, so the total number of persons affected might have been many times higher.[29]

Figure.

Reported incidents of facility-associated poliovirus release from laboratories and manufacturing sites in the pre–polio vaccine era (shown inside dashed-line frames) and the time of poliovirus vaccine introduction to the present (shown inside solid-line frames). AFP, acute flaccid paralysis; IPV, inactivated poliovirus vaccine; MEF-1, wild poliovirus type 2 laboratory reference strain; WPV, wild poliovirus; WPV3, wild poliovirus type 3.

In the 3 decades since the WHA resolution to eradicate poliomyelitis and the formation of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) in 1988, seven documented incidents underscore the potential for facility-associated release of polioviruses into the community in the modern era. In 1991, a WPV3 (Saukett strain), probably from a laboratory source, was isolated in France from a woman from Algeria. A year later, a worker in a vaccine manufacturing facility in the Netherlands transmitted a WPV1 (Mahoney strain) used for IPV production to his son.[30] In another incident in the Netherlands in 1993, a child with a travel history to France was reported to have been infected with a strain of WPV3 (Saukett strain) almost identical to that used for IPV production in France. The possibility of laboratory contamination was ruled out, and environmental samples collected from around the child's home and among his family contacts were negative for poliovirus in cell culture. The source of this infection was not determined.[30] In India, 2 incidents were reported during 2000–2003 after the interruption of WPV2 transmission in 1999. A WPV2 laboratory reference strain (MEF-1) was recovered from 3 poliomyelitis patients in September 2000 and 7 patients during November 2002–February 2003. The sources of these infections were not identified.[31–33]

In September 2014 in Belgium, ≈1013 infectious WPV3 particles were released into the sewage system from a vaccine production plant.[34] Subsequent investigations revealed no evidence of WPV3 in samples from a range of environmental samples.[35] More recently, in the Netherlands, WPV2 (MEF-1 strain) was accidentally released as an aerosolized high-titer spill when tubing became disconnected in a vaccine production room. One exposed staff member became infected and shed the wild virus strain for ≈4 weeks before testing negative by fecal culture, whereas a second staff member who was also present at the time of the spill did not test positive for poliovirus in throat swabs or stool samples.[12] No acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) cases or secondary spread to household contacts was detected.

Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2019;25(7):1363-1369. © 2019 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)