As he did with many of his Wings-era songs, Paul McCartney peppered his 1974 non-album single “Junior’s Farm” with a cast of incongruous characters in improbable situations.

Throughout the early to mid-1970s, freed from the self-seriousness of John Lennon — who, similarly, was freed from the surrealist silliness of McCartney — the former Beatle created four-minute worlds of whimsy.

Joining the undertaker, the jailer, Sailor Sam and the county judge from “Band on the Run” and the sergeant major and the lady suffragette (is there any other kind?) from “Jet” is the troupe from “Junior’s Farm.” There’s the poker man, the Eskimo (forgive a Liverpudlian in 1974 for opting for the easy rhyme rather than the correct nomenclature), a sea lion, Junior himself, Jimmy, the president (oddly, at the House of Commons; maybe it’s the Lord President of the Council), comedy legend Oliver Hardy, an old man and a grocer.

Like a Sid and Marty Krofft retelling of The Canterbury Tales, these disparate figures are all thrown together for Macca to play with: a cast of incongruous characters in an improbable situation. And “Junior’s Farm” — along with its B-side, “Sally G” — is the product of a cast of incongruous characters in an improbable situation.

This is the story of the summer Paul McCartney and his retinue spent in, of all places, Lebanon, Tenn.

In late 1973, Wings released Band on the Run. After some previous middling efforts from the band, the record was a triumph. Two singles — “Jet” and the title track — both went gold. The album went to No. 1 and was triple platinum in the United States, and has since become regarded as a classic and one of the greatest albums by an ex-Beatle.

A critical and commercial success far outpacing Wings’ two earlier releases, Band on the Run was recorded in Lagos, Nigeria. McCartney attributed the success of the album — at least in part — to having left the United Kingdom to lay down tracks.

Eager to tour the record, McCartney wanted a similar away-from-Britain summer camp feel for himself, his wife Linda, their children and the other members of the band as they worked out new tunes and got ready for their triumphant turn on the road.

Now, it would be easy to assume McCartney wanted to live on Curly Putman’s farm because of Putman’s reputation. By 1974, he’d already won songwriting accolades for “Green, Green Grass of Home” and “D-I-V-O-R-C-E.” Six years later, in 1980, he’d write “He Stopped Loving Her Today,” now considered one of the greatest country songs of all time. This was clearly a man with chops, and even McCartney could certainly bask in his reflected genius.

That would be a nice story: Rock legend comes to the middle of nowhere to learn at the feet of a country music Yoda.

The truth is a lot more prosaic.

Linda McCartney’s father was Lee Eastman, the copyright attorney for, among other entities, Buddy Killen’s legendary Tree Music Publishing. So Eastman asked Killen to find somewhere in the pastoral verdancy of Tennessee for his daughter and his famous son-in-law and his grandkids and some pals to hang for six weeks.

One of the heavy hitters for Tree happened to be Curly Putman.

Putman, who died in 2016, told The Wilson Post in 2009 that he and Killen cruised all over the Nashville area looking for the right place. Killen called farms in the area and played it close to the vest as to who he was representing. But farmers are practical people, and they knew anyone who wanted to rent a farm for six or seven weeks sight unseen and was represented by a music power player like Killen had to have deep pockets. One farmer said Killen’s client could have his place for seven weeks for $200,000 (about $1.2 million in 2022) and he’d be able to pay off his mortgage.

Eventually, Killen took Putman along on his quest through the countryside, but in hindsight, that may have been a setup. After all, Putman lived in a great big white house with acres of pasture and plenty of horses, plus a swimming pool and a fishing pond.

“Finally, [Killen] sweet-talked me and Bernice into leasing our place to them,” Putman told the Post’s Ken Beck. “I was kind of nervous. You know how rock ’n’ roll bands were back then? They paid me pretty good for leasing it for six weeks. And they didn’t tear anything up.”

His nerves eased and his bank account robust, Curly — more officially, Claude Putman Junior — and his farm were about to stake a corner of rock ’n’ roll trivia.

Wings wasn’t exactly Led Zeppelin. The McCartneys brought their daughters Heather, Stella and Mary along with Wings members Denny Laine, Jimmy McCulloch and Geoff Britton.

The entourage landed at Nashville Municipal Airport — Nashville International these days — June 6, 1974.

It was a relatively low-key arrival. It didn’t exactly resemble the Beatlemania of a decade prior or even the swarming crowds and marching bands Robert Altman put on the same tarmac the next year for Barbara Jean’s return in his film Nashville. There were 40 or so fans and lookie-loos and a handful of reporters.

In a 2002 interview with the Scene, Killen — who died in 2006, memorialized by a roundabout featuring Nashville’s most famous nudes — said he’d done his best to keep the trip on the down-low.

“I’m terribly protective of the artists I work with,” Killen told the Scene, “and I kept Paul’s arrival very hush-hush.”

The deal made and the check cut, the Putmans (Curly, Bernice and their then-12-year-old son Troy) hosted a reception for the McCartneys, which Bernice said was just as down-to-earth and normal as any other Wilson County family stopping by for a visit. The Putmans spent a few days in Nashville — they popped back a time or two to find that Wings had converted their garage into a practice space; Troy rode horses with Heather — and then headed to Hawaii and the West.

Wings made themselves at home. They had endless crates of oranges delivered (the McCartneys loved freshly squeezed orange juice) and stayed stocked in Johnny Walker Red (for the grownups) and Ovaltine (for the girls).

Curly told Troy to put his dirt bike away before the family took off. Troy said he tucked it away in a small shed, but McCartney must have gone snooping, because one of the persistent memories of Lebanon residents of a certain age is seeing one of the world’s most famous men speeding around the sleepy little town atop that Honda XR75 (that had no headlights or taillights). Linda, who was a talented photographer, took dozens of photos of Paul on the bike, some of which were published around the world — a dirt-biking Paul was even spotted by the vacationing Putmans.

And spotted by a state trooper.

Putman’s farm was on Franklin Road about halfway between Lebanon proper and the unincorporated area known to locals as Gladeville. The area is in Tennessee’s unique cedar glades. (That’s the “xerohydric calcareous glades” for the deeply scientific; the “cedars” that give the glades and in fact Lebanon its name are actually junipers.) It’s a web of narrow and winding backroads, some with charming names only found in small towns. The fact that Chicken Road and Tater Peeler Road never made lyrical appearances in a McCartney song is truly one of the great upsets of his career.

Anyway, Paul liked to take Troy’s bike out on these little two-lane blacktops. He one day found himself chugging along near what is now Cedars of Lebanon State Park, near the still-extant flea market, just where Highway 231 slopes down to the very bottom of Middle Tennessee’s Central Basin.

Well, Paul wasn’t wearing a helmet. And that bike — without requisite lights — wasn’t street legal in any case.

A Tennessee Highway Patrol officer flicked on the lights and sirens. The trooper, Charles Douglas, who surely was gobsmacked at his quarry, let McCartney go with a warning and then called his son Robert.

Robert, coincidentally, was the manager at Lebanon’s Hunt Honda, and sure enough, the next day Paul and Linda came in looking for a motorcycle. Wanting something he could, y’know, actually ride on the road, McCartney opted for the 124cc XR125.

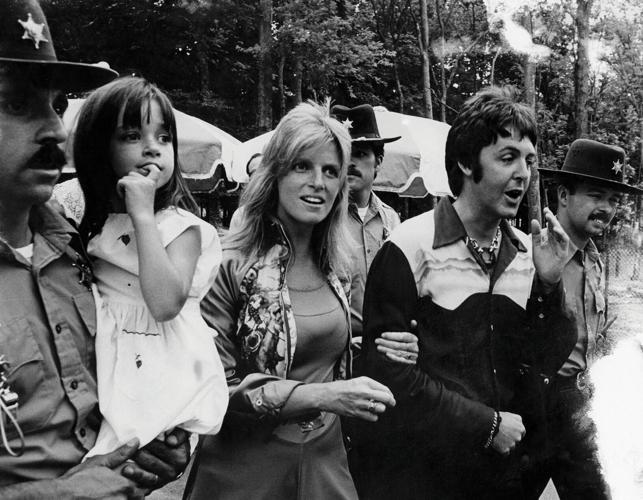

Paul McCartney on the Grand Ole Opry grounds with his wife Linda, escorted by police

That wasn’t Wings’ only encounter with the police. Guitarist McCulloch, just 19, was actually arrested for reckless driving. Killen pulled strings to get him out of jail, but the charge put McCulloch’s visa status in jeopardy and nearly led to the cancellation of the Wings Over America Tour.

McCartney & Co. spent their first week or two rehearsing and, among other things, getting acquainted with the Putman’s housekeeper, whose daughter told the Post’s Ken Beck that Paul liked his barbecue “charred” (even Homer nods) and that the famously vegetarian Linda gave her a recipe for carrots and turnips that she continued to make. But then, Wilson County’s most famous visitors decided it was time to see the big city, such as it was. Paul, after all, had told the Nashville Banner on his arrival: “I rather fancy the place. It’s a musical center. I’ve just heard so much about it that I wanted to see for myself.”

The whole crew headed out to Opryland, naturally. Killen, for reasons he still couldn’t comprehend almost 30 years later, actually pulled up and bought tickets like a regular Joe rather than seeking freebies for the McCartneys et al. While at Opryland, the group took in the third annual Grand Masters Fiddling Contest. Porter Wagoner and Dolly Parton happened to be playing a few tunes between the grand masters grand-mastering, and Killen said as the group approached the two country music icons, it wasn’t long before fiddle fans recognized Paul. But the old pro just autographed what was handed to him and moved along until Opryland security was able to corral him into a VIP area. Killen, who said it never occurred to him how crazy such a scene could be, said McCartney told him one of the enduring lessons from Beatlemania was to just keep moving.

In one of those moments that seems contrived to the point that even the hackiest screenwriter wouldn’t include it in a script, that performance by Porter and Dolly was the last time they’d perform together. After a few tunes and a few snaps with Dolly and Porter (Mary looks thoroughly unimpressed by all the musical icons surrounding her), the crew stopped by Kentucky Fried Chicken — presumably Linda just had biscuits or something — and the McCartney filles wiped gravy all over the newly painted walls at Killen’s home.

Killen — who honestly seemed as dumbfounded by children as he was by celebrity — decided it was time to take in the sights of Nashville, lest his walls become permanently gravy-scented. Stella, then just 3 and now, of course, a renowned fashion designer, ran headlong through the glass front door, shattering it and ending up bloody and needing a mend at the old Donelson Hospital on Lebanon Pike.

Tour rehearsals were the raison d’être for the Wilson County decampment, though as the trip to Opryland and Paul’s new love for dirt bikes demonstrated, there were plenty of side trips. This wasn’t pure cenobitism. The crew met Johnny and June Cash at their place across the lake in Hendersonville. They hung out with Chet Atkins and Jerry Reed. They fell in love with The Loveless Motel, Killen telling the Scene the McCartneys visited the beloved biscuit business over and over. Paul and Linda loved taking the girls to drive-ins, presumably as it was an easier way for one of the world’s most recognizable men to take his daughters to the movies and remain relatively unbothered.

And Killen took Paul down to Printers Alley, still in the early ’70s a relative free-for-all rather than the stage-managed theme park version it has since become.

And from Printers Alley the great mystery of the Wilson County Summer begins.

“Junior’s Farm” was the big hit that Wings recorded while in Nashville, but its B-side, “Sally G,” also did reasonably well on its own and nearly cracked Billboard’s country Top 50, something of which Paul — who had the English affection for country music that was more or less factory-standard for Brit musicians of his era — was quite proud.

Unlike “Junior’s Farm,” with its nonsensical characters and odd plot, “Sally G” was fairly straightforward, explicitly setting its story in Nashville with a title character who “sang a song behind a bar” in Printers Alley. Killen insisted, including to the Scene, that Paul and Linda wrote it in his car as Killen was driving them back to Lebanon after dinner at The Captain’s Table and a few digestifs at Hugh X. Lewis Country Club.

The late David “Skull” Schulman said Paul wrote it alone at a back table at Skull’s Rainbow Room after hearing one of the club’s singers belt some tunes. Her name was Diane Gaffney, and the song, Skull insisted, was originally “Diane G.” This is the version that’s most often repeated on the scores of Beatles fan sites.

Killen’s and Schulman’s versions agree the song was written in one shot after a visit to the city’s famed block of vice, but even that may not be totally true.

The housekeeper’s daughter — the one who let slip the unfortunate revelation about Sir Paul’s predilection for overdone pulled pork? Her name is Sally Palmer, and she told The Wilson Post’s Ken Beck that Paul laughed at the coincidence when they were introduced, because he was “writing” a song called “Sally G” (not “Diane G”). In other words, in that telling, “Sally G” was a process and not born full-sized like Athena.

Paul, for his part, said later there was no singer — Sally or Diane or otherwise — who tried to woo him in Printers Alley, and the whole tale was just a product of his imagination.

Wings recorded seven songs at Sound Shop studio in Nashville, and that was exactly seven more than the law allowed. Technically, recording songs (particularly, as with “Junior’s Farm” and “Sally G,” ones destined for commercial release) is work, and technically, the British subjects in the band didn’t have the necessary visas to work. In fact, Putman told Beck he tried to get Wings on an episode of Hee Haw (a show the band loved, he insisted), but there were worries a TV appearance might catch the unwanted attention of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

So the band settled for some not-exactly-clandestine but not-exactly-wholly-public recording sessions. And it was still Nashville, which meant Paul had access (maybe whether he wanted it or not) to the city’s inestimable sidemen. Lloyd Green played steel guitar on “Sally G,” with fiddle parts from three absolute stone-cold legends: Vassar Clements, The Texas Playboys’ Johnny Gimble and the Texas Playboy himself, Bob Wills.

Beyond the two best-known songs from the sessions, the most interesting story might be that of an instrumental called “Walking in the Park With Eloise,” which was released as a single as well. Just don’t seek it in the Wings discography. The band put it out under the name The Country Hams (a nod to their Loveless fandom, perhaps), and it included the members of the band plus Chet Atkins, country piano legend Floyd Cramer and Clements. Paul played a washboard he bought at a flea market.

The writing credit went to Paul’s father, Jim, who wrote the Dixieland-adjacent instrumental stomper for his own band decades earlier. The elder McCartney was sick — he’d die in 1976 — and Atkins told Paul to cut the song as a gift.

Paul actually did one better. Despite doing the arrangement and other assorted cleanup work on it, he assigned sole credit to his father. In a 1984 Playboy interview, Paul said when he told his dad, his father said “Son, I didn’t write it.” Briefly panicked that a barrage of lawsuits would be coming his way, Paul was reassured when his father explained that while the song was his idea, he didn’t write it, as in he didn’t put notes on a staff. He couldn’t annotate a tune, but then again, neither could Paul.

Among the few observers of these recording sessions was a young up-and-coming radio man named Mike Bohan. In the nearly 50 years since, Bohan has been a fixture in Nashville broadcast media, sidekicking Gerry House for years as part of the country radio behemoth The House Foundation, among other notable accomplishments. He was inducted into the Tennessee Radio Hall of Fame in 2014. But in 1974, he was two years out of high school and working with the already legendary Coyote McCloud at WMAK-AM. Near the end of Wings’ month-and-a-half at Junior’s farm, Paul decided he’d hold a small press conference. WMAK, naturally, said they’d send McCloud, but the DJ asked Mike if he wanted to come along.

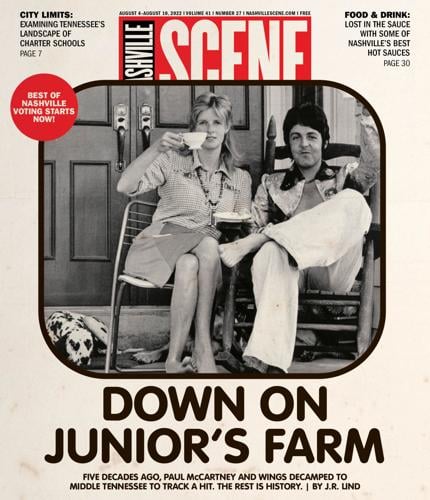

When the radio men arrived, Paul and Linda were set up on Putman’s big white front porch, Paul demonstrating how well he’d embraced early-’70s Nashville in a truly remarkable white-and-red rhinestone suit and Linda having side conversations with the press who’d come out to Lebanon. Their daughters skittered about nearby.

There was a little Nashville radio rivalry playing out as well, though of course the McCartneys couldn’t have known. WLAC sent Dick Downes, who had been on the air on WMAK until Scott Shannon — another Nashville radio legend — fired him and replaced him with the younger (and “cooler”) Coyote.

In any event, there’s Mike Bohan — long before his famous ubiquitous beard graced his face, but with hair down to his shoulders — gripping a mic and a tape recorder, as McCloud, for reasons Bohan never figured out (and never will, as McCloud died in 2011), took pictures instead of conducting the interview as originally planned. So Bohan — just barely in his 20s — found himself interviewing one of the most famous men on earth on a porch in Lebanon.

In the retelling, he’s way too hard himself for the questions he came up with.

“Really, really pathetically lame,” he says.

OK, so maybe Lester Bangs wouldn’t have asked Paul McCartney what he thought about Anne Murray’s cover of “You Won’t See Me” or if the former Beatle wanted a WMAK T-shirt of his very own. But how many people have digitized versions of an old tape recording of themselves interviewing a bedazzled former Beatle on a Wilson County front porch? Not Bangs. (It was local press only.)

After the mini-gaggle broke up, Wings went back to the studio to finish mastering their septet of tunes. Emboldened by McCartney’s graciousness from earlier in the day, Bohan decided to swing by Sound Shop. Linda came out to the lobby for a chat (and a smoke from a joint large enough Bohan remembers it 48 years later), and Bohan could hear the strains of Wings’ output wafting down the hall.

He followed the music and peeked through a door to see Paul and the engineer working out the final bits and pieces. A nod from Paul — Bohan read it as “dismissing” — and Bohan slipped away.

Paul and the band left Nashville July 18, as agreed. He begged Putman to let him stay just a few more days, but the Putmans were ready for Junior’s Farm to be theirs again. Paul had his new dirt bike shipped back to New York and wrote “Quite a pad!” in a thank-you note to the Putmans.

And all of Curly’s worry about what a handful of rock ’n’ rollers might do to his beloved farmhouse was, of course, misplaced.

Kind of. Ultimately, a few of the upstairs bedrooms did need some repainting.

Stella — already a budding artist, and already having covered Killen’s walls with KFC gravy and broken his door — had drawn on the walls in crayon.

Paul and Linda McCartney near the end of their stay in Lebanon, Tenn., July 18, 1974