COLEHARBOR, North Dakota — Paul Anderson has dubbed his new irrigation project "Double-0 Seven" -- buts it's not because it’s a secret.

In fact, he’d like more people to know that the new irrigation is from the the famed Garrison Diversion Conservancy District.

Why Double-O Seven?

It’s literally .007 miles from the headgates of the McClusky canal. “About 35 feet,” farmer Anderson said, smiling as he gave a recent tour of his construction effort.

ADVERTISEMENT

Since 2018, Anderson has seen weather trending drier. In 2021, he committed to constructing a project that will be operational in 2022.

“We will wet-test everything this fall yet,” he said.

North Dakota’s dam

A bit of background: Lake Audubon is a “major sub-impoundment” of Lake Sakakawea, the reservoir created by the Garrison Dam on the Missouri River, completed in 1953.

ADVERTISEMENT

The dam initially was for flood control and navigation in central states. Farm irrigation was supposed to be part of the compensation to North Dakota for flooding fertile lowlands.

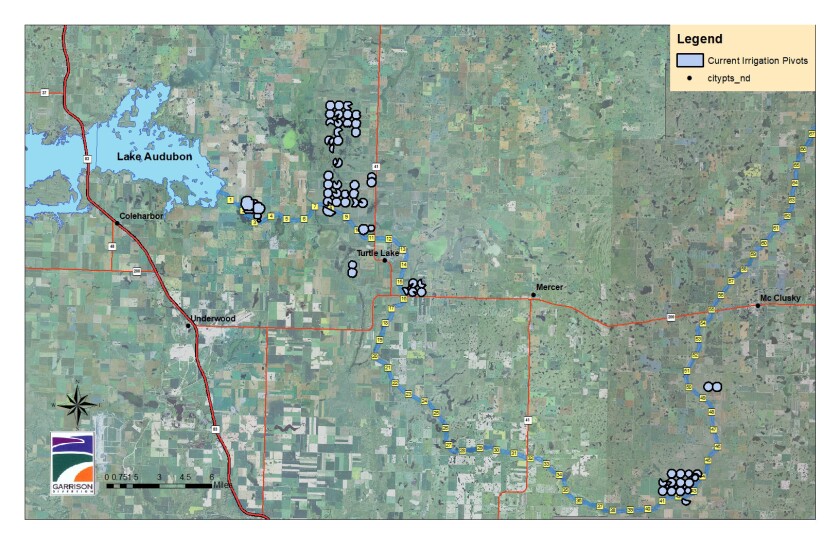

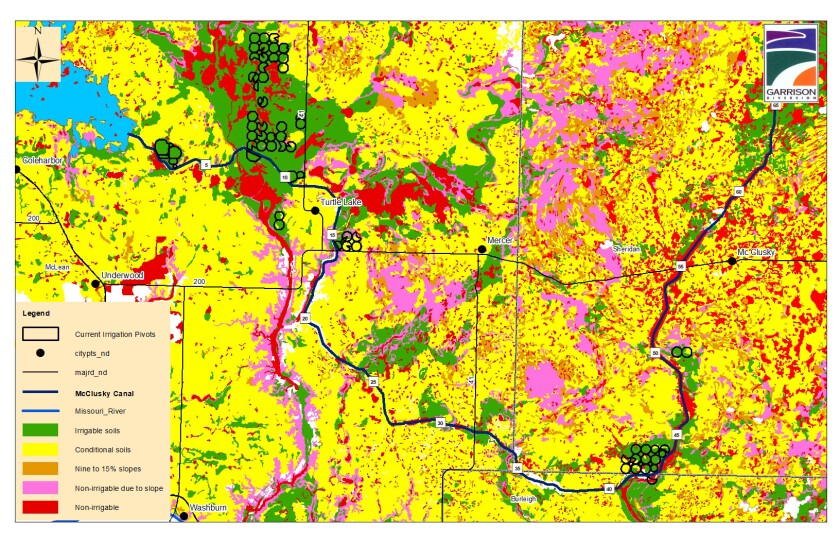

The McClusky Canal is 73.6 miles long and was built from 1969 to 1976. It was designed to take water from Lake Audubon to the Lonetree Reservoir (later deauthorized and made into a wildlife management area, managed by the state).

The state Garrison Conservancy District manages the canal — 15 feet deep, 25 feet wide at the bottom, about 84 feet wide on the surface. The district manages it in a “cooperative agreement” for the federal Bureau of Reclamation, an agency within the federal Department of the Interior.

There were lofty aspirations for the McClusky Canal.

It was built to carry 1,950 cubic feet of water per second, but only delivers a fourth of that today, based on demand. It was built to irrigate up to 250,000 acres of farmland, plus provide water for municipal and rural water systems.

The canal is authorized to irrigate only 23,700 acres. And only 7,200 acres is allocated. In the middle of the drought, the Anderson project is the only one currently in the works, adding 610 acres over the next two years.

ADVERTISEMENT

Sweet and sour

Paul, 54, and his wife, Joleen, live with their son, Augustus, 7, on the farm at Coleharbor, just south of Lake Audubon in central North Dakota. Paul’s parents, Richard “Rick” Anderson and mother, Charlotte, live at the farm shop site one mile south of the headgates.

The Andersons operate an average-sized farm for the area, raising wheat, corn and soybeans, as well as sometimes confection sunflowers, lentils and dry edible beans.

Rick, now 80, grew up in the Pembina/Neche area in northeast North Dakota, in the northern Red River Valley. He graduated from North Dakota State University in 1966, with a degree in agricultural economics.

At age 26, Rick held a 150-acre beet sugar allocation from American Crystal Sugar Co. (prior to it becoming a farmer-owned cooperative in 1974). Rick had an opportunity to rent another 125 acres to raise beets, but the corporate Crystal managers balked. “They weren’t going to let a kid be that big a beet farmer,” Paul said.

So in 1968, Rick and Charlotte packed to moved west to the area where her parents had homesteaded in 1906. Farmland prices were cheaper. Wheat yields were roughly the same at the time.

Ebbs and flows

As the McClusky Canal was being dug, wheat prices soared in the wake of the huge Russian grain purchase in 1973. The grain economy overheated and led to the farm credit crisis in the 1980s . Land values declined, loan interest rates soared and prices collapsed.

ADVERTISEMENT

Then came the 1988 and 1989 drought.

With crops in surplus, farmers couldn’t use water from federal sources (a refuge lake or canal) to produce federally-subsidized “program crops” — like wheat, corn and soybeans.

In the midst of all of this, Paul graduated high school in 1984. He went on to North Dakota State University where he got his bachelor’s degree in mechanized agriculture in 1989. He went on to get master’s in agricultural economics in 1992. As the drought abated, he considered going for a doctorate, but came home to farm.

In 1986, Rick was elected to represent his county on the Garrison Diversion Board, which governs the district. (Rick is still on the board but recuses himself from Paul’s irrigation issues and never applied for his own irrigation permit.)

ADVERTISEMENT

Making hay

In 1991, young Paul went goose hunting with a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service manager in charge of the Audubon National Wildlife Refuge. The manager agreed that he could pull irrigation water directly from Lake Audubon for crops and put some of the water in the refuge as habitat for nesting waterfowl. From 1991 to 1993, he put in three pivots for 500 acres.

Under the rules of the time, Paul could only use the water for non-program crops — like alfalfa hay.

“We were doing long hours in the hay, dealing with a lot of hay customers, being on-call to load hay out at odd hours,” he said.

But it was challenging.

In 1992, the Andersons got their first cutting of alfalfa hay on the ground, and then it started raining.

“And it pretty much rained every year,” Paul recalled. “Good, green, quality hay that you got up with no rain on it? That hay ran out of the shed with people throwing money at you. But once it got rained on, nobody wanted the rained-on hay at a price we could recover our costs out of.”

ADVERTISEMENT

And if a year came where hay production wasn’t plentiful or was expensive?

The federal government responded by opening access to the Conservation Reserve Program, a land idling program.

“That really knocked the stuffing out of the bottom end of the hay market,” Paul said.

By 1996, the Andersons were done with hay. They sold their hay equipment and went back to conventional non-irrigated cropping. That year, Congress passed the “Freedom to Farm” bill, which changed the rules, allowing water from the canal to apply to program crops.

In 2014, the USFWS changed its policies to tighten up commercial activities throughout the country. Paul could no longer pull water from the lake. He parked his irrigation rig — temporarily.

Back to the future

Some 15 years ago, the Garrison Conservancy started encouraging canal-side irrigation.

Agweek in September 2013 wrote about the Knorr family from the Sawyer area who initiated the so-called “7.2 Project,” named for the number of miles from the headgate. The Knorrs have grown potatoes on some of their land and control a number of circles.

Rick’s land largely is too rocky for irrigated potatoes.

“When my dad came out here in 1968, some of this ground was pasture that you could walk across without touching the dirt because there were so many rocks on it,” Paul jokes.

In the current drought trend, Paul decided to get back into irrigation for other crops. But the cost has gone up.

"In the 1990s, a new pivot system cost about $30,000,” Paul recalled. “Today, a brand new pivot is over $100,000 to quarter-section center pivot.”

Paul is paying $30,000 for a “new to us” pivot. The late-1980s model has been updated with new gear boxes and new electronics.

“The pipe is sound, the nozzles are good,” he said “We’ll get it running.”

All told, the new irrigation will cost $70,000, for electrical and pipe under the ground.

“Putting in the pipe, getting the pumps refurbished, and some electrical, it’s considerably expensive to do it,” he said.

The North Dakota State Water Commission and the Garrison Diversion District have a 50-50 cost-share program growers can use to help out with the cost of pipe, pumps and electronics to get the water to the edge of their property. Paul repurposed some 12-inch diameter aluminum pipe they had a few years ago and he refurbished pumps.

Variable rates

Paul will add a variable-rate irrigation system, which is relatively new. He’ll be able to shut off zones in the field where he doesn’t want to add water.

The USDA’s National Resources Conservation Service is funding a grant to help out with that project. The NRCS offers some grants to help producers convert from less-efficient flood irrigation to center-pivot irrigation.

“For our situation, we’re accessing the variable-rate irrigation project to help not put water in areas where pivots would be getting stuck and getting muddy,” Paul said. “Part of it is to have a variable frequency drive so we can control the speed of the pump. When we get to an area where we don’t need to put on so much water, it slows the pump down so our flow rate matches what actually needs to be coming out of the nozzles.”

Paul’s center-pivot has 11 towers which will be divided into 22 zones — cutting each tower in half.

Without irrigation, Paul’s produces 60 to 70 bushel per acre corn. With irrigation, yields are 150- to 180 bushels. His heavier soils produce 120 non-irrigated and should hit 180 to 200 bushels per acre with irrigation.

Paul said irrigation will help take the variability of production. In effect, the current drought is prompting an investment he hopes will serve his family up to 40 years.

“I want to make this as durable and carefree for my son to be able to irrigate someday,” Paul said. “Hopefully he can take over the farm someday.”