We All Crave Them - Porsche + The Atlantic Re:think Partnered to Understand Why

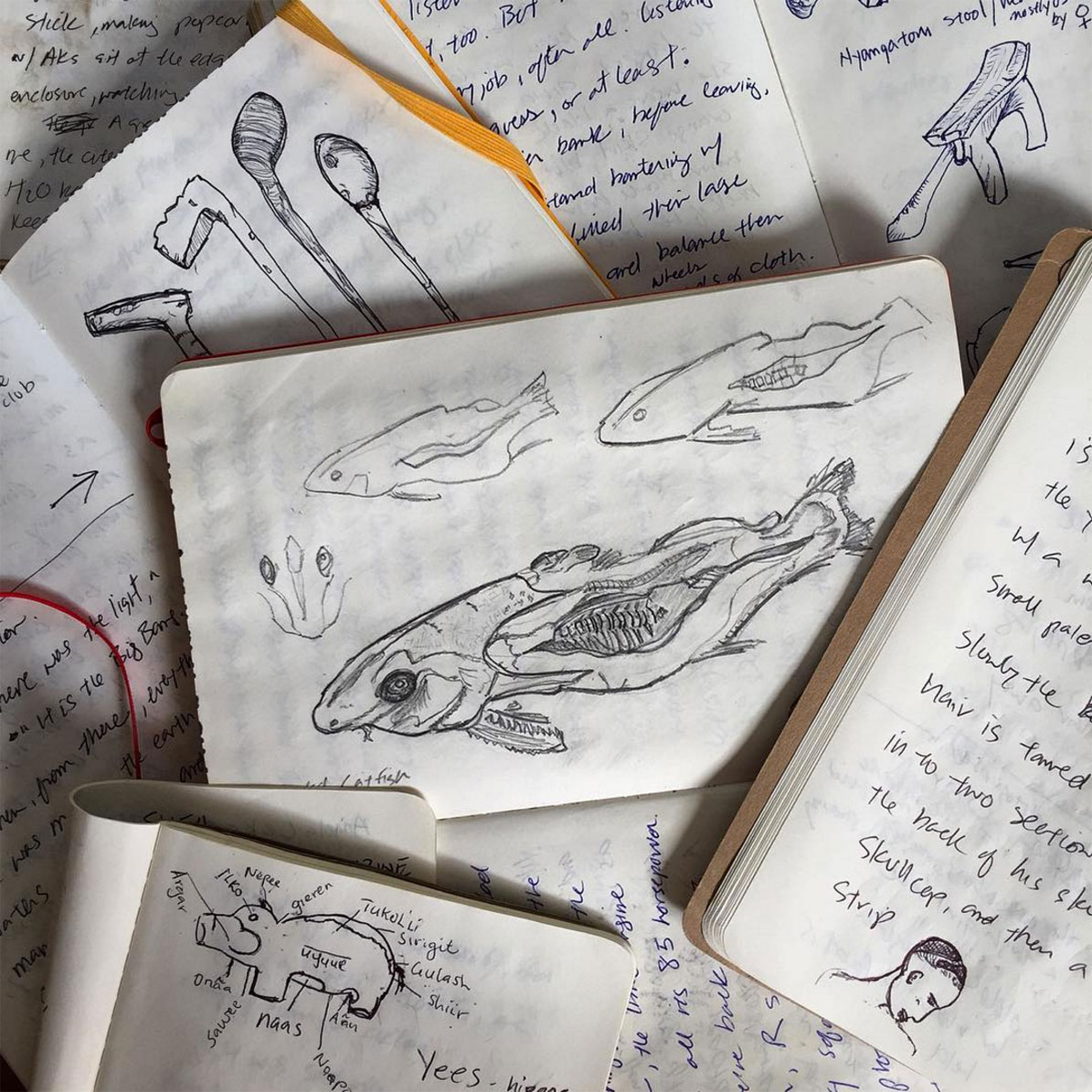

Illustrations by Valeris

VIDEO Hard-wired – 1:45

Exploring the evolutionary roots of thrill-seeking behavior

VIDEO Hard-wired – 1:45

Exploring the evolutionary roots of thrill-seeking behavior

Watch the full video

Clint Kugler felt it while climbing 18,000 feet up the side of Volcan Cayambe in Ecuador. Zach Fackrell recognized it as he came face-to-face with a 19-foot shark off the coast of Fiji. It struck Neil Shea as he interviewed a traditional healer in a remote region of Africa, and James Lee is trying to get back to it by wakeboarding at 40 miles an hour. Though recognized in wildly different settings, the feeling was always the same: the pay-off of a thrill.

“It’s like having superpowers for a very brief time,” says Margaret King, Ph.D., director of the Center for Cultural Studies & Analysis in Philadelphia.

The rush starts in the amygdala, a bundle of neurons at the base of the brain responsible for assessing the unknown. In a thrill-seeking situation—which almost always poses some kind of risk, whether perceived or real—the amygdala registers that risk, then releases a combination of dopamine, adrenaline, endorphins, and other chemicals in order to protect the body against it. How much of each is released depends on the perceived level of risk. At the peak, every bodily function, chemical brain reaction, and sensory input is hyper-focused on the experience.

The Sensation Seekers

By the 1970s psychologist Marvin Zuckerman, Ph.D. had created a personality survey that identifies four types of sensation seekers. Explore the different sensation seeking types here.

take the quiz What's your sensation seeking subtype?

Every person’s brain assesses unknown situations differently: Those with thinner sections of gray matter, for example, tend to perceive less of a threat and therefore seek greater thrills. No matter what type of thrill a person is seeking, the reaction triggers an increase in testosterone. Vision narrows. Adrenaline shoots into the body, which increases heart rate. With the heart beating faster, we get more oxygen. The body redirects oxygen to the brain as fast as it can. The feeling often lasts less than 60 seconds, and the immediate aftermath is another flood of mood-boosting chemicals. This is what leads thrill-seekers to chase the process again and again.

The Chemistry Behind The Thrill

-

1

The amygdala releases a combination of chemicals that includes adrenaline, dopamine, and endorphins. Dopamine has many functions in the brain, including telling the brain that there is a potential reward if this threat is overcome.

-

2

As the response intensifies, the brain sends testosterone streaming into the body. This boosts strength, giving the person a better chance of success.

-

3

Adrenaline also shoots into the body, which increases heart rate.

-

4

With the heart beating faster, the brain and muscles gets more oxygen. The body reroutes this oxygen to the brain as fast as it can.

“It has a biological basis and high heritability, which suggests that it’s coded in our genes and our nervous system,” says psychologist Marvin Zuckerman, Ph.D. Now a professor emeritus at the University of Delaware, Zuckerman started studying the field in the 1960s. “Our early ancestors survived on hunting and food gathering,” he explains. “Hunting was one of the early expressions of sensation-seeking, particularly when they began to hunt large mammals where there's a high risk involved.” High-altitude climbing and wakeboarding today produce the same chemical reaction in the brain as fighting a woolly mammoth with a spear likely produced in 15,000 B.C. Back then it was a matter of survival. In today's far safer world, it's a matter of pleasure.

By the 1970s Zuckerman had created a personality survey that identifies four types of sensation seekers: people looking for adventure, people seeking new experiences, people looking for ways to lose inhibitions, and people susceptible to boredom. People looking for adventure are likely to pursue physical challenges such as skydiving or base-jumping. People seeking new experiences often visit exotic places or try unfamiliar foods. People seeking to lose inhibitions thrive on making social connections with new people, while people susceptible to boredom often crave novelty. Most people fall into multiple categories, Zuckerman showed, but the pay-off is the same.

“You realize everything else in the world is shut out, and a calming sensation comes in. It’s zen,“ says James Lee. “It’s real. It’s very real.“

VIDEO Hard-wired – 1:45

Exploring the evolutionary roots of thrill-seeking behavior

In addition to identifying the four subtypes, researchers also developed what they call the “Sensation-Seeking Scale”. High-sensation seekers spend their lives pursuing this fleeting feeling. Low-sensation seekers actively avoid thrills and new experiences. Most of us fall somewhere in the middle of this scale, which correlates to certain aspects of brain makeup and chemistry as well as individual tolerance for exhilaration.

This tolerance develops as brain and body begin to anticipate that we will survive whatever we have survived in the past, which deprives similar experiences of their thrill and demands a new and greater challenge to achieve the same sensation. Factors that influence an individual’s tolerance include the amount of white and grey matter in the brain and mutations in certain genes. Researchers suspect variations in dopamine receptors are another factor, but the research is preliminary.

No matter what type of thrill a person seeks, part of the pleasure comes from the simple act of concentrating fully on a single task, according to the work of Dr. Seymour Epstein, late professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts. “It makes you feel very alive to be so scared,” he told the New York Times. “When you react to something that demands your full attention so forcefully, all your senses engage.

The Sensation Seekers

By the 1970s psychologist Marvin Zuckerman, Ph.D. had created a personality survey that identifies four types of sensation seekers. Explore the different sensation seeking types here.

take the quiz What's your sensation seeking subtype?

“After you take the plunge there's an immense relief and sense of well-being in facing a fear that doesn't materialize,” he adds. That’s the payoff sensation Fackrell and Lee describe as time standing still.

King and her colleague Jamie O’Boyle have found similar results while researching the appeal of rollercoasters. According to their findings, the peak moment of exhilaration comes from experiencing a risk you know will be survived. On a rollercoaster, logic tells us we will be safe, but our bodies and brains respond to more than logic, and as the fear response overpowers intellect, we become disoriented. Our bodies turn all energy to their survival systems, halting everything else. At the end of the rollercoaster ride—or the high-altitude hike, or a close encounter with a tiger shark—we experience the moment of survival as a thrill.

For high-sensation thrill-seekers it might take being all alone in the world at 18,000 feet before dawn to feel the disorientation that leads to exhilaration. For many of us, being strapped into a rollercoaster is disorienting enough to produce that moment. In many ways, chasing thrills is similar to chasing a drug-induced burst of feeling. “You’re high,” O’Boyle says. “We know it’s a high because of the crash afterward, when it wears off.”

Thrill-seeking is behavior unique to humans. Mammals in the wild don’t seek out challenges just for the sport of it. We humans, on the other hand, keep chasing ever more exciting thrills because, as O’Boyle puts it, “It’s a really significant piece of who we are as humans. As a memory, it comes back as the joy of realization of what it really means to be alive, even for only a minute or two.”

QUIZ

What's your sensation-seeking subtype?

For each question, please indicate which of the choices most describes your likes or the way you feel. When it is hard to choose, select the option that describes you best or that you dislike the least.

This quiz was adapted from Dr. Marvin Zuckerman’s Sensation Seeking Scale Form V. While most people exhibit characteristics spanning across all 4 sensation-seeking subtypes, this quiz is designed to show you which subtype(s) you lean toward most.

Select One:

Choice OneI like to explore a strange city or section of town by myself, even if it means getting lost

Choice TwoI prefer a guide when I am in a place I don’t know well

Click to reveal your type