The Planet-Saving, Capitalism-Subverting, Surprisingly Lucrative Investment Secrets of Al Gore

The former vice president has led his firm to financial success. But what he really wants to do is create a whole new version of capitalism.

“When i left the White House in 2001, I really didn’t know what I was going to do with my life,” Al Gore told me this summer, at his office in the Green Hills district of Nashville. “I’d had a plan”—this with a seemingly genuine chuckle rather than any sign of a grimace—“but … that changed!” After the “change,” via the drawn-out 2000 presidential election in which he won the vote of the populace but not that of the Supreme Court, for the first time in his adult life Gore found himself without an obvious next step. He was 52, two years younger than Barack Obama is now; he hadn’t worked outside the government in decades; and even if he managed to cope personally with a historically bitter disappointment that might have broken many people, he would still face the task of deciding how to spend the upcoming years.

Some of the answers he found are known to everyone. He connected himself with the leading tech firms of the era, Google and Apple. In 2005 he and a partner launched Current TV, which in 2013 was sold to Al Jazeera for several hundred million dollars. Throughout his political life he was poor compared with many senators; now by any standard he is rich. According to his financial-disclosure forms, Gore was worth between $1 million and $2 million when he ran for president. Gore declined to discuss his personal finances with me, but published estimates of his net worth are in the hundreds of millions. He was the most prominent U.S. politician to issue an early warning against the impending invasion of Iraq, which he did in a speech in California in September 2002. His first book about climate change, An Inconvenient Truth, was a No. 1 international best seller. The movie version won two Oscars, the audiobook won a Grammy, and for his climate work Gore was a co-winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007.

Gore is still involved on most of these fronts. He has become a partner in the Silicon Valley venture-capital firm Kleiner Perkins and is a member of the Apple board. He founded and chairs an advocacy group called the Climate Reality Project, travels constantly for speeches, and has published several books since An Inconvenient Truth, including another No. 1 best seller, The Assault on Reason. I asked him how he divided his time among the projects. “Probably a little more than half on Climate Reality,” and then half on some other commitments. “And then probably another half on Generation.”

The object of this final “half” is Generation Investment Management, a company that is rarely mentioned in press coverage of Gore but that he says is as ambitious as his other efforts.

The most sweeping way to describe this undertaking is as a demonstration of a new version of capitalism, one that will shift the incentives of financial and business operations to reduce the environmental, social, political, and long-term economic damage being caused by unsustainable commercial excesses. What this means in practical terms is that Gore and his Generation colleagues have done the theoretically impossible: Over the past decade, they have made more money, in the Darwinian competition of international finance, by applying an environmentally conscious model of “sustainable” investing than have most fund managers who were guided by a straight-ahead pursuit of profit at any environmental or social price.

Their demonstration has its obvious limits: It’s based on the track record of one firm, which through one decade-long period has managed assets that are merely boutique-scale in the industry’s terms. Generation now invests a total of about $12 billion for its clients, which are mainly pension funds and other institutional investors, half U.S.-based and half overseas. For comparison, total assets under management by BlackRock, the world’s largest asset-management firm, are about $5 trillion, or 400 times as much. But for investment strategies, the past decade has been a revealing one, with its bubbles, historic crashes, and dramatic shifts in economic circumstances in China, Europe, and every other part of the globe.

During that tumultuous time, from the summer of 2005 through this past June, the MSCI World Index, a widely accepted measure of global stock-market performance, showed an overall average growth rate of 7 percent a year. According to Mercer, a prominent London-based analytical firm, the average pre-fee return for the global-equity managers it surveys was 7.7 percent. This meant that after fees, which average about 70 “basis points” (or seven-tenths of 1 percent), the returns an average professional money manager could produce barely kept up with plain old low-cost, passive index funds. Individual investors have heard this message (“You can’t beat the market, so why try?”) for years, from index-investing firms like Vanguard. The Mercer analysis says that it applies even to the big-endowment pros.

But through that same period, according to Mercer, the average return for Generation’s global-equity fund, in which nearly all its assets are invested, was 12.1 percent a year, or more than 500 basis points above the MSCI index’s growth rate. Of the more than 200 global-equity managers in the survey, Generation’s 10-year average ranked as No. 2. In addition to being nearly the highest-returning fund, Generation’s global-equity fund was among the least volatile.

Gore is obviously delighted to discuss the implications of his firm’s success. “I wanted us to start talking when the five-year returns were in, but cooler heads persuaded me that we should wait until now,” he told me. But he says he is not doing so to attract more business. The minimum investment Generation will accept in its main fund is $3 million, and even then individuals must show they have total assets many times that large to be “qualified investors.” And besides, its most successful fund is now closed to new investment. Instead he and his colleagues are aiming at a small audience within the financial world that steers the flow of capital, and at the political authorities that set the rules for the financial system. “It turns out that in capitalism, the people with the real influence are the ones with capital!,” Gore told me during one of our talks this year. The message he hopes Generation’s record will call attention to is one the world’s investors can’t ignore: They can make more money if they change their practices in a way that will, at the same time, also reduce the environmental and social damage modern capitalism can do.

“We are making the case for long-term greed,” David Blood told me in July. Blood is Generation’s senior partner and on-scene leader at its headquarters in London. The formal name for the concept he and Gore are advancing is sustainable capitalism, which sounds both more familiar and less hard-edged than what I understand to be the real underlying idea. The idea is that if some tenets of “long term” and “value based” investing are extended to include the environmental and social ramifications of corporate activity, the result can be better financial performance, rather than returns that are “nearly as good” or “worth it when you think of the social benefits.”

I asked David Rubenstein, the billionaire co-founder and co-CEO of the Carlyle Group, the private-equity firm, what he thought of Generation’s aspirations and its business model. “The general theory in investing is that the highest returns go to those who are unencumbered by sustainability or other environmental and social constraints,” he said. Generation’s “pitch that the conventional wisdom is wrong may be right; their record would be a good barometer.”

“They are indeed unusual, in applying such a comprehensive sustainability perspective,” Dominic Barton, the global head of McKinsey, said when I asked him about Generation’s approach. “They have created a real demonstration vehicle for the idea that if you are broad-minded and care about externalities, you can actually add shareholder value. Many people have talked about this, but now they have done it.” The economist Laura Tyson, of UC Berkeley, who is part of Generation’s unpaid advisory board, said that Gore and Blood were “genuine pioneers” in showing the practicality of their investment approach. “When they started, very few people believed that a sustainability strategy could offer competitive returns,” she told me. “Their hypothesis has been borne out by their results.”

No single small company is going to change finance by itself, and Generation’s past results are no guarantee of its future. But previous examples of market success—Peter Lynch of Fidelity in the early mutual-fund days, Warren Buffett of Berkshire Hathaway with his emphasis on the long term, David Swensen of Yale with his returns from unconventional investments, John Bogle of Vanguard with his advocacy of low-cost indexing—have shifted behavior. Generation’s goal is to present an example of a less environmentally and socially destructive path toward high returns.

The chain of logic behind this argument starts with the assumption that capitalism has shown its superiority to all other systems—as Gore put it to me, “it has proven to unlock a higher fraction of human potential” than any alternative system for making money—and markets are the most efficient way to allocate resources. But markets often overshoot, creating bubbles and busts like the destructive subprime real-estate disaster of the 2000s, and through its history the global capitalist system as a whole has periodically overshot, causing national or worldwide crises. The financial and industrial crises of the late 19th century led to reforms in the United States (and revolution in Russia) but were never fully resolved in Europe. The more profound crisis of the Great Depression led to the modern welfare state.

The capitalist crisis of our times, to follow this logic, shows up in the recurring booms and busts, the widening gaps between rich and poor, and the intensifying pressures on the natural environment. In many countries, including the United States, overall growth has stagnated through the past decade, and the median income has fallen even while total wealth has gone up.

In one way or another, all of these problems are related to faulty market signals or destructive incentives within today’s capitalism. Since the 2008 financial crisis, a growing number of economists, managers, and financiers have warned that ever shorter time horizons are destroying businesses and entire economies. For instance, this spring Laurence Fink, the CEO of BlackRock, sent a cautionary letter to hundreds of CEOs. As a group, he said, they were too attentive to short-term profitability and stock values, at the cost of the long-term welfare of their firms. “The average Fortune 500 CEO has a term of only five years,” Fink told me. “If you’re going to build a new factory in a manufacturing company, the break-even point is probably longer than that. In pharmaceuticals, the payoff time may be more than twice that long. There’s an incentive not to reinvest. You see these behaviors, year after year, and it’s a big problem.” Dominic Barton, of McKinsey, has written or co‑written three influential articles in the Harvard Business Review on the pernicious effects of short-term pressures. According to a 2012 Harvard Business School study, simply issuing quarterly profit guidance, which most Wall Street analysts demand, led managers to overemphasize immediate returns in a way that reduced long-term profitability.

So far these might sound like lessons from one of Warren Buffett’s annual letters to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, or the pre-IPO letter from Google’s founders on why they were determined to resist short-term profitability pressures.

The sustainable-capitalism concept includes a long-term outlook, a search for underlying value, and an attempt to resist distraction by market ephemera. But it adds the idea that the real, dollars-and-cents, balance-sheet value of a company is best assessed by including factors deliberately left out of many business measurements. Among them are a company’s environmental effects, the culture it creates internally, and its impact on the societies in which it operates.

This contention involves some elements that seem blandly commonsensical, like the importance of matching pay and incentive structures with a company’s long-term interests. But others are anything but conventional. For instance, Warren Buffett considers Coca-Cola a wonderful long-term value proposition, because of its decades-long track record of worldwide success. By Generation’s standards, it is distinctly unsustainable, since obesity problems in all of its leading market countries will, in the firm’s view, inevitably do to the soda industry what public-health concerns have done to Big Tobacco.

Generation’s best-known analysis is its 2013 report asserting that coal and petroleum reserves were “stranded assets” whose theoretical market value would never be realized, because environmental, legal, technological, and market constraints would inevitably prevent much of that carbon from being sold and burned. Generation argued that the bankruptcies, write-downs, and market declines that had battered the coal industry in the past decade would soon extend to oil companies. As a prominent Harvard alumnus, Gore has said that the university’s endowment should divest itself of carbon-based assets. “But I say that not just because it’s the ‘right’ thing to do but because it is the economically smart thing to do,” Gore told me. “Oil companies have assets on the books worth $21 trillion, but that’s based on the fiction that all that carbon is going to be burned.”

***

Seeing More of the “Spectrum”

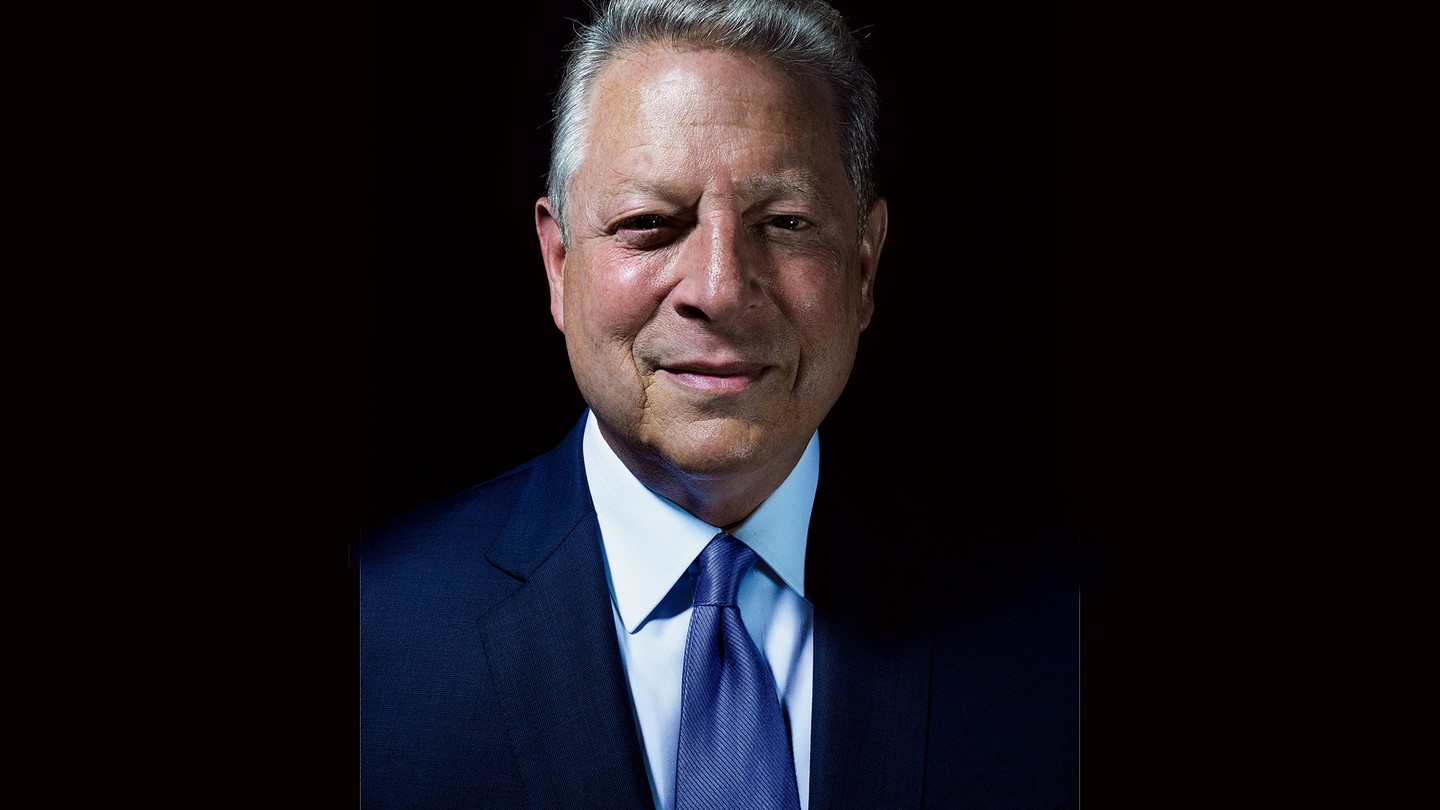

I’ve observed, interviewed, and slightly known Gore over the decades, and have been on better and worse terms with him over that time (based mainly on what I had most recently written about him). It’s common knowledge that his physical appearance varies. When I saw him this summer, he looked good—sturdy rather than portly, tall and erect, hair now gray rather than jet-black but still present and combed straight back. His speaking mode has also varied by year and by setting: sometimes loose and wisecracking, sometimes ponderous and slow. When I spoke with him through a long afternoon in Nashville this summer, he seemed to have evolved a jokey enjoyment of his own weakness for pedantry.

For instance: As I first walked into his office, he showed me a big photo of the Earth, like the famous Blue Marble picture from Apollo 17 that everyone has seen. This one showed Africa and Europe, rather than the Americas, as in the Apollo shot. “Nice!,” I said, or something similar. He realized he had an opening for a little tutelage, so he explained to me why this photo, far from nice, was something extraordinary.

It turned out that the familiar Blue Marble picture was not just the best-known “full disk” picture of the Earth. It was, according to Gore, the only one of that exact type ever taken—until, that is, a few days earlier, when a NASA satellite had produced the second-ever photograph, the one Gore was now showing to his underappreciative visitor. Gore had initiated the Deep Space Climate Observatory satellite program, known as DSCOVR, when he was vice president; Dick Cheney personally zeroed out its funding as soon as he could, and the program went into hibernation until the Obama administration revived it. After more than 40 years in which one Blue Marble photo of the Earth existed, DSCOVR would start producing photos every day. “I love explaining this!,” Gore said—and obviously he did. But he also seemed to be taking some arm’s-length amusement, in a way I had not seen him do during his competitive political career, at the spectacle of himself giving this little lecture.

He loved the spectrum even more. Halfway through our talk he asked politely, “Has anyone mentioned the metaphor of the spectrum, as a guide to our work?” I said that, as it happened, during my recent visit to the Generation Investment headquarters in London, every single person had mentioned it to me. It was a core part of company culture. And I was actually holding in my hand a chart that explained the concept. And …

“Oh, that’s great!” he said, and sat looking a little disappointed for a moment. Then he brightened. “But this is important, so I’d just like to explain …”

So now let me explain! We all know that there’s a spectrum of visible light, from red at one end, with the lowest-frequency waves, to violet at the other, with the highest. Everyone has also heard in science class that visible light is only a small part of the full electromagnetic spectrum. The spectrum extends in a vastly broader range than we can see. Just below red, on the low end, it goes first to infrared and then farther down to microwaves and radio waves. On the high-frequency end, it goes from violet to ultraviolet and then up to X-rays and gamma rays. But until 200 years ago, people had no idea that the nonvisible parts of the spectrum even existed. “We can see less than one-tenth of 1 percent of what’s really there,” Gore said, making sure I got the point. “We were blind and didn’t know what we couldn’t see!”

The reason everyone at Generation uses this analogy is that it matches their ambition: to improve investment choices by bringing more information into the range of the visible rather than leaving anything out. (The other two words they use all the time are sustainability, which of course is their central precept, and holistic, to describe their inclusive analytical approach. I’ve gone this far in my journalistic career without feeling compelled to use holistic; I deploy it here as part of my reportorial duty.)

From Generation’s perspective, most of what passes for “financial” analysis—the focus on price-to-earnings ratios, the daily chatter on why the markets moved, the screaming on the cable shows, the speculation about the Federal Reserve—is equivalent to the tiny slice of the entire spectrum human eyes can see. It’s hard to detect the full extent of the spectrum, but Generation believes that attempting to do so can make businesses both more sustainable and more profitable.

When the spectrum model is applied to investing, it means a subtly but significantly different approach from some of the “ethical investing” approaches of the past. For as long as there have been buyers and sellers, borrowers and lenders, people have considered using market power for noneconomic ends, as in boycotts of British tea by the American colonialists in the 18th century and boycotts of the products of American slave labor in the 19th. The current ethical-investment movement dates to the 1960s, when students pressured their universities to rid endowments of holdings in defense contractors or big polluters. The most famous political success of what is called a “negative screen” approach—ruling out certain categories of investment—was the anti-apartheid boycott of South African products and businesses in the 1980s and early 1990s. But all of these methods viewed “ethics” as a minus, the unavoidable cost of doing the right thing. The people at Generation, of course, contend that the “holistic” and “sustainable” view is a business plus, in the service of long-term greed.

They have more evidence to draw on than just their own. The most comprehensive recent research in this field, released last year by economists at Oxford University in collaboration with the investment firm Arabesque, drew on 190 academic studies and news reports about businesses that had and had not applied sustainability policies. The business-world term for these policies is ESG, meaning that in addition to normal profit-and-loss calculations a company factors in the environmental, social, and governance effects of what it does. In spectrum-analogy terms, these are policies that broaden considerations beyond the narrow range of visible light. (A related concept is that of the “triple bottom line,” promoted by the British consultant John Elkington starting in the 1990s. This is the idea that, in addition to the normal financial profit-and-loss bottom line, corporations should also be measured by the bottom line of their environmental and social effects.) The Oxford-Arabesque report found overwhelming evidence that “it is in the best economic interest for corporate managers and investors to incorporate sustainability considerations into decision-making processes.” According to the study, the advantages include more stable (and less volatile) revenues, significantly lower cost of capital, higher profits, and better share-price performance.

In an ongoing series of speeches, the Bank of England’s chief economist, Andrew Haldane, has similarly emphasized that firms and investors that widen their perspective and look beyond this quarter’s or year’s results can earn predictably higher returns than those that don’t. Most people who have taken economics courses would say: That can’t be so! If the returns really were higher, everyone would already be investing this way. Arbitrage would even out the returns. (In economics courses, this is known as the “$20 bill paradox”: An economist sees some money lying on the sidewalk and says, “That can’t be a $20 bill, because if it were, someone would have picked it up.”) But Haldane’s analysis shows a persistent market failure because of habits of mind, compensation structure, and other real-world factors that make investors undervalue long-term returns. Thus there are potential increased rewards for those who can organize themselves to think differently and buck the trend.

***

When Gore Met Blood

“I won’t be one of those people saying, ‘Oh, it wasn’t about the money,’ ” Gore told me about his early postelection work for an asset-management firm called Metropolitan West, based in Newport Beach, California. “I am telling you straight up, it was about the money. They were very nice people, and they offered me enough money to get my attention.”

After a year of work, Gore had improved his finances and found the intellectual exercise of asset management—matching insights about opportunities and challenges to bets on particular firms—to be truly interesting. “I decided that I wanted to continue in the business, but I wanted to do it on my own terms,” he told me. By 2003 Gore had made enough money to consider buying an investment company, and looked hard at one in Switzerland called Sustainable Asset Management. A friend at Goldman Sachs was advising him in this investment and said: You don’t really want to buy a company. What you want to do is meet David Blood.

Then in his early 40s, Blood had enjoyed a conventionally successful finance career, starting from an unconventional background. He grew up in the prosperous suburbs of Detroit, where his father was an executive with Ford. When he was 11 and headed into sixth grade, his father was reassigned to Brazil, and the whole family moved to São Paulo. Each morning, through the window by his breakfast table, he could look out directly onto a Brazilian slum, or favela. “I could throw a baseball into the house of a boy my age,” he told me when I met him in London. “I wondered how it was that I was here and he was there. That has bothered me all those years since, the disparity in income and wealth. It was a moment that led to the founding of Generation.”

Blood came back to the United States for high school, was a star football linebacker at Hamilton College, in New York, and planned to become a child psychologist. But he didn’t get into graduate school, and his application for the Peace Corps was turned down. “My father said, ‘You have to get a job,’ and the only offer I got was from a bank.

“I’d never thought about finance, but I found I was okay at it,” Blood said. Over the next decade, he thrived. After his first job, with Bankers Trust, he went to Harvard Business School. His most formative experience there came during the summer between his first and second year, when he worked for the then-famous, now-defunct (through merger) brokerage firm E. F. Hutton. “Everything about the culture seemed wrong to me,” he said. “Everything was short-term-focused, with no sense of what would help the client in the long run.” This was around the time that a young bond trader named Michael Lewis was observing something similar at the also now-defunct Salomon Brothers. Lewis converted his insights into his first book, Liar’s Poker.

Blood developed an enduring interest in the way a firm’s internal culture governed its success. “There were companies that had the same toxic short-term culture in those days—Drexel, Salomon, Bear Stearns, Kidder, Lehman,” he told me. “They’re all gone. If you look at what happened to them, it was all failures of culture: governance, leadership, incentive structures, values. That’s why they failed. And that was the beginning of my view that long-term business success requires a holistic view, involving teamwork, integrity, values.”

He said he found the values he was looking for at Goldman Sachs, a firm that then prided itself on a noblesse-oblige culture of putting its investors’ interests first. Blood rose in the organization, was transferred to London, and by the time he met Al Gore in 2003 had become the head of Goldman’s asset-management division, overseeing 1,600 people and managing $325 billion in investments. He had also become a U.K. citizen, although unlike some other Yankee expats he does not sound ersatz British when he talks.

Just when Gore was turning to Goldman Sachs for advice on buying the Swiss asset-management firm, Blood was preparing to leave. Their mutual friend at the firm introduced Blood to Gore, and they immediately agreed they should work together. “It was obvious that we were both searching for the same holy grail,” Gore told me, “which was a way to manage assets with sustainability built into every part of the model.”

They considered buying the Swiss firm and other possibilities, but finally agreed that their best chances lay with what Gore calls the “long, slow approach”: starting their own company, whose structure, values, analytic approach, and payment schemes would be designed the way they wanted. In early 2004 they founded Generation with five other like-minded partners. They spent the rest of that year establishing the firm’s operating rules, objectives, and even its own new vocabulary, which they considered important for a group determined to reconceive investment.

To get this out of the way: The obvious joke about their collaboration is that the firm should have been named Blood and Gore. The joke is so obvious that nearly everyone I spoke with about Generation mentioned it. Overobviousness, along with forced jocularity, no doubt helps explain why the founders chose a different name. But Gore and Blood both emphasized another reason, which reflects the values they hoped to build into the firm: There were seven partners, not two, at its founding. Gore and Blood are now first among equals, as chairman and senior partner, respectively. (Gore spends about a week a month at Generation’s office in London, and several more days at its office in New York. He joins, by phone, weekly management-committee meetings, and he told me that he spends part of nearly every day in online or telephone contact with Generation analysts.) In the details of its daily work, Generation incorporates a team-based rather than star-dominated approach to decision making.

***

How It Works

In practice, seeing more of the spectrum involves a disciplined, complex, multilevel process, which I heard about in London. I’ll highlight just three of its aspects.

The road map. The starting point for many of Generation’s investment decisions is a set of “road map” reports, on the long-term business, environmental, and social aspects of emerging technologies or markets. The Generation team, which now numbers more than 60 people in London and another 11 in New York, has produced more than 100 of these reports, on topics ranging from the worldwide spread of diabetes to changes in the heating-and-air-conditioning industry, which (with elevators) can account for nearly half the total energy use in big cities. I am looking as I write at a report on the environmental and workforce implications of the rapid rise in data-storage centers, the physical incarnation of the “cloud.” Next to it is one on the “last mile” question of online commerce: how products ordered over the Internet make their way into customers’ hands, and whether the dynamics are more likely to make delivery companies—the postal service, FedEx and DHL, and eventually Lyft and Uber—into retailers, or instead convert retailers such as Costco and Walmart into their own deliverers. And another report on the environmental, workforce, and urban-planning ramifications of those models and others. I’ve read a lot of these reports now. When they touched on topics I knew about, such as the manufacturing supply chain in China, or the business future of the media and the political and social effects of that changed future, I thought they rang true. The rest gave me a better understanding of, say, sustainability issues in the fashion industry, and equipped me to learn more.

The company also runs occasional multiday “solutions summits” on major topics for its analysts, held at its headquarters in London and presided over by Gore. This June it held one on “The Future of Mobility,” meant to explore what changes in city planning, self-driving cars, battery and engine and drone technologies, business models like Uber’s, and other areas would mean for companies ranging from Tesla to Priceline. As I read the records of some past summits, I realized that they were more, well, holistic than events I’d heard of or seen elsewhere. Compared with those at universities or government agencies or think tanks, they were more tied to business opportunities. Compared with those at other financial firms, they took a broader historical and intellectual view.

The focus list. Based on the road maps, summits, and other sources of guidance, Generation’s analysts begin researching specific companies. They travel to the headquarters and interview managers and board members. They tour factories; they learn about competitors. They check sites like Glassdoor.com, where former employees discuss what they liked and didn’t like about a firm.

Once a week, about 25 members of the analyst team sit around a big conference table in London to discuss a company that has been the target of such research. They know that at the end of the meeting, they will each be asked to assign the company a value on two scales, BQ and MQ. BQ stands for “business quality,” a measure of whether the firm is likely to enjoy better-than-average long-term profitability. Does it have a “moat” against competitors? Is its whole industry vulnerable to disruption? Does it have a strong enough brand to avoid ruinous price competition? MQ stands for “management quality,” which encompasses not merely the character and intelligence of the executives and board members but also how closely their personal interests are aligned with the firm’s. Do their payment schemes encourage them to cash out or front-load the company’s profits and thus underfund long-range investments? Are they respected or resented by employees at large? Built into both assessments is consideration of the company’s social and environmental effects. Neither a very profitable business with disastrous environmental side effects nor a well-meaning company with weak revenues would qualify for investment.

Presiding over these meetings are Generation’s two co–chief investment officers, Mark Ferguson and Miguel Nogales. I heard the shorthand “Mark and Miguel” at Generation almost as often as I heard references to “Al.” (No one there seems to call him “Vice President Gore”; they viewed my reflexive use of the term as a weird Americanism.) Ferguson and Nogales, both in their 40s, make up an odd-couple leadership team. Nogales grew up in southern Spain, in a family of doctors and medical professors. He came to England for high school and then went to Cambridge, where he earned a degree with highest honors in economics. If you had to guess, based on bearing and diction, who at Generation was from the English upper class, you would choose the man from Spain.

Mark Ferguson is a Scot who says he finished high school only because he injured his knee in a soccer game when he was 16 and gave up his dream of going pro. “I come from a football family,” he told me. This was wry understatement: His father is the longtime Manchester United manager Sir Alex Ferguson, probably more recognizable on a London street than Al Gore.

Both Ferguson and Nogales went into finance early and thrived. But in their 30s each was looking for a way to combine it with his environmental and social-justice interests. Ferguson had worked, at different times, with both Blood and Nogales; Blood introduced them both to Gore; and in 2004 they were all part of the founding team. (The other three founders were a young asset manager named Colin le Duc; Gore’s former chief of staff, Peter Knight; and Peter Harris, of Goldman Sachs.)

At the focus-list meeting I attended, Ferguson and Nogales guided the conversation rather than weighing in themselves, taking care to draw out even the soft-spoken or introverted analysts and those less comfortable in English. The business under discussion at that session was a well-known U.S.-based technology firm, which I am not supposed to name. On the good side, it held a wide market lead, and some of its technologies had shown potential in helping low-capital entrepreneurs in Africa, India, and elsewhere. On the bad side, other technologies might leapfrog its entire market category. Analysts argued the pros and cons. And was the pay structure likely to keep the best executives on board? An analyst making a case about the strengths of a company is also supposed to prepare an imagined corporate obituary, listings the things that went wrong and led the company to fail.

When it came time to vote on business quality and management quality, everyone around the table held out a closed fist, palm down. Then, on a count of three—“rock-paper-scissors” style—each person at the table put out one to five fingers, ranking first the company’s BQ and then its MQ. This company got a BQ3 and an MQ3.

“We came up with the rock-paper-scissors plan because we found that if Miguel or I indicated our feelings, that would inevitably steer things,” Ferguson told me.

What struck me when the process was over was what I had not heard during the long back-and-forth: namely, any mention of the company’s stock price. “That would really be frowned on at this stage of discussion,” Nogales said when I mentioned this to him the next day. “It would suggest a misunderstanding of what we’re trying to do.”

He meant separating the judgment about whether a company is sustainably profitable from the decision about when to buy its shares. The initial judgment is made, collectively, at the focus-list meeting. If a company scores 3 or better on both measures, it is added to Generation’s focus list. That list now has about 125 entries. These are the firms whose stock prices and earnings Ferguson and Nogales watch closely, so they can buy if and when the price falls into what they consider an attractive range.

Some companies have been on the list for years but have never become cheap enough to buy. Nogales told me, for example, about a European biotech firm that Generation considers a top-ranked BQ1/MQ1. Unfortunately, the rest of the investing public has also recognized its virtues, keeping the price too high. In other cases Ferguson and Nogales have bought when the price was right—and then kept buying as the price went into a slump. For instance, in 2007 Generation bought 5 percent of the total shares of Kingspan, an Irish company that had invented a dramatically effective form of building insulation. During the ensuing collapse of the world’s construction business, the company’s share price plummeted from 22 euros all the way down to 2. Generation increased its holdings as the shares fell; the price is now back in the 20s.

“Our sustainability analysis has given us the conviction to have very concentrated positions in companies we think have the right long-term earning potential,” Nogales told me. Some of these bets have gone wrong—an early stake in First Solar, an Arizona-based company whose solar panels were underpriced by Chinese competitors and whose business results fell short of Generation’s assumptions. But enough have gone right to give Generation the performance record on which it is now making its case.

Active ownership. This is the third distinctive trait of the Generation approach. Mark Ferguson said that in a normal firm, 80 percent of the attention is on the buy decision and 20 percent on the sell, leaving zero percent for owning shares in a company. From Gore and Blood on down, everyone I spoke with at Generation said they viewed the attention scale entirely differently. Their real responsibilities began rather than ended when they bought shares of a firm.

Generation officials meet with board members and managers of companies they invest in, explaining exactly what they like about the business and what kinds of decisions they’re hoping to see. “We talk directly with them about compensation levels, about board structure, about sustainability practices they are considering,” Nogales said. “Typically board members and CEOs will tell us that we’re the first institutional investors ever to talk about these issues. You should not underestimate the influence this can have on CEOs. We are trying to give cover to people who want to do things in a different way.”

***

Reinventing Capitalism?

At Generation, I could tell that I had slightly hurt Mark Ferguson’s, Miguel Nogales’s, and David Blood’s feelings by not acting more awestruck at what I was seeing. To me, the analyst reports and discussions resembled good versions of what I’d seen and heard over the years from scientists discussing opportunities and obstacles in a field they knew well, or entrepreneurs weighing prospects for a new business. The Generation officials emphasized that if I had spent more of my life in the financial world, I would understand how profoundly their deliberative process varied from the investment-house norm. In particular, it was not based on a star system, in which leading analysts cultivate their contacts and play their hunches. Nor did it involve the normal sort of quantitative analyses of general market trends.

“If you want to get an idea of the difference, spend a few minutes watching CNBC,” Blood told me. Pay systems at financial firms are typically based on year-by-year or even quarter-by-quarter profits; staff turnover is rapid, driven by higher pay offers elsewhere. Bonuses for Generation’s investment team are based on its funds’ performance over a three-year period. Annual turnover has been about 3 percent through Generation’s history, very low for the financial world.

When I was able to look at the complete focus list of 125 companies under ongoing consideration, and public U.S., U.K., and European regulators’ reports on the companies in which Generation holds active positions, I was at first puzzled about just what made this lineup so special. Of the three dozen companies in which Generation reported holdings as of June 30, its largest holding was in Microsoft. No. 2 was Qualcomm, the leading chip maker for the mobile-phone industry, and the top 10 also included Google and the company that makes John Deere tractors.

I asked David Blood how this constituted any kind of reinvention of capitalism. He reminded me that Generation was trying to realize two goals usually considered contradictory: making a lot of money and supporting sustainable businesses. Every company on the focus list—big or small, household name or obscure start-up—had passed Generation’s internal test of offering good long-term business prospects. The big, familiar names were in one way or another advancing a sustainability goal. Microsoft, according to Nogales, met the test of “providing goods and services consistent with a low-carbon, healthy, fair, and safe society,” while also being (in Generation’s perhaps contrarian view) an attractive long-term business. Qualcomm was notable for its market position and its leadership in clean manufacturing and energy-efficient processing chips. John Deere? Equipment that supported “precision agriculture,” which could increase crop yields while reducing demand for energy, water, and chemical inputs. For the past six years Generation has held shares in Unilever, which it considers a proponent of sustainable agriculture around the world. A major cause of deforestation throughout the tropics is clearing forests to open land for palm-oil plantations, and the market for palm oil is dominated by big companies like Unilever, P&G, Nestlé, and L’Oréal. Unilever, the single largest palm-oil purchaser, has coordinated international efforts toward sustainable palm-oil production.

Once I looked past the likes of Microsoft and Qualcomm, I saw that about a third of the companies on Generation’s holdings list, and the great majority of those on its larger focus list, were ones I had simply never heard of before, even in fields I felt familiar with. I asked about them and learned that many made ambitious environmental or social-benefit claims. For instance: Ocado, an online-only grocery company based in England, has no physical stores. It claims to be able to deliver your selections to your house for a lower total energy/carbon cost than if you walked to a store yourself, and at much greater savings than if you drove. (Main reason: It avoids the extreme energy intensity of operating a chain of normal grocery stores, where the cooling and heating systems are working against each other, and where so much fresh food goes unsold and spoils. Instead Ocado uses an Amazon-esque model of stocking food in its own few warehouses, where rapid stock turnover minimizes spoilage. The energy costs of its sophisticated home-delivery network are less than those of a chain’s distribution system.) A firm called Ansys, based in the small Pennsylvania town of Canonsburg, has developed simulation software that allows engineering companies to skip many stages of creating physical prototypes, thus saving time, energy, and materials. Other Ansys products allow companies to model and reduce the environmental effects of their operations. Linear Technology, based in Milpitas, California, north of San Jose, dominates the market for sensors and related devices for electric and hybrid vehicles (which can use five to 10 times as many of them, per vehicle, as conventional cars).

I asked about many other companies and heard many similar rationales. Some concerned a firm’s environmental or public-health effects; others, exceptional market power. All arose from the long BQ/MQ analytical approach.

When I pressed Gore and Blood on whether this assortment of companies, plus Generation’s undeniably successful first-decade performance record, had more than niche significance, they said they recognized the risks of overstating their achievement. But they said it should not be underappreciated, because they had provided at least one counterexample to the assumption that reducing the destructive side effects of modern capitalism would necessarily mean reducing its success. Political strategies change when a candidate comes out of nowhere to win. Coaches and athletes must adapt after losses if they hope to win again. The Generation strategy had proved a winner by the standards capitalism cares about most.

“When a new model appears that shows consistent results that beat the average, that model is sought after,” Gore told me. “Even if most assets are still allocated to index funds or by algorithmic traders, a prime part of the world’s assets are reserved for managers who think they can beat the market. That is what we have done. Our goal is to show that sustainability is a ‘best practice’ for doing this, and thus for changing the culture of the investment marketplace. I know that sounds pretty grandiose, but it’s our aim.”

Many other people suggested to me that world finance is ready for such a push. Laurence Fink, of BlackRock, said that he wrote his open letter to CEOs because “I truly believe we need to have inclusive capitalism, progressive capitalism”—a system that can be “stronger, more resilient, more equitable, and better able to deliver the sustainable growth the world needs.” Fink said that countless pressures, from hyper-fast automated trading to the frenzied tone of cable-news coverage, were steering managers toward destructively shortsighted behavior. “We decided that we needed to be a countervailing voice, to say that as your largest shareholder, we’re going to raise expectations about how you behave.”

Dominic Barton, of McKinsey, has written extensively about the leverage that investors and boards can have in deterring short-term, unsustainable corporate behavior. With Fink and other asset managers from Europe, North America, Asia, and elsewhere, Barton has been organizing an effort to convert major investors to a longer-term outlook. “We have something like $10 trillion in investable assets lined up here,” he told me. “This is not a small-potatoes amount, and it can send a very powerful signal.” Laura Tyson, of Berkeley, says that sustainability strategies of one kind or another are now “by far the fastest-growing category of assets under management.”

In his book Capitalism 4.0, published in the wake of the worldwide crash of 2008–09, the British financial writer Anatole Kaletsky argued that capitalism has survived so long because of its ability to adapt and mutate. In times of deep crisis—the brutal inequality of the first Gilded Age, the mass unemployment of the 1930s, financial instability and environmental pressures today—governments sooner or later intervene. “At these historic moments, when the capitalist system appears to be in its death-throes, it also seems incapable of radical reform,” he wrote. But just then, “politics kicks in to shake up institutional structures … [and] a reformed version of capitalism takes shape.”

“Reform” sounds boring and earnestly high-minded, criticisms that have been applied to Al Gore as well. But having lost some of the major fights in his life, he has earned consideration for the implications of this win.