On Friday, August 16, at around 7 a.m., a pair of suspicious appliances was found on a subway platform at the Fulton Street station in lower Manhattan and, an hour later, a third near a garbage can on West 16th Street. Initially, police thought they might be improvised bombs, like the shrapnel-filled pressure cookers that blew up at the 2013 Boston Marathon and in Chelsea in 2016, but upon inspection they turned out to be harmless empty rice cookers, probably meant to scare but not explode. Trains were delayed during the morning commute, but since that happens often enough without any terrorist help at all, the scariest thing about this episode may have been the way the alleged perpetrator was caught.

Minutes after the discovery, the NYPD pulled images of a man leaving the devices from subway surveillance cameras and gave them to its Facial Identification Section (FIS), which ran them through software that automatically compared his face to millions of mug shots in the police department’s database. The program spit back hundreds of potential matches in which officers quickly spotted their person of interest: Larry Griffin II, a homeless 26-year-old the NYPD had arrested in March with drug paraphernalia. FIS double-checked its surveillance pictures against Griffin’s social-media accounts, and by 8:15 a.m., his name and photos were sent to the cell phones of every cop in New York. He was arrested in the Bronx late that night and charged with three counts of planting a false bomb. (He pleaded not guilty.)

This might seem like a feel-good story: A potentially dangerous person was identified and apprehended with previously impossible speed and no casualties thanks to by-the-book use of new technology (or newish; the NYPD has used facial-recognition software since 2011). But zoom out a little and it looks more like a silver lining on one of this year’s biggest feel-bad stories: The facial-recognition system that ensnared Griffin is only a small piece of a sprawling, invisible, privacy-wrecking surveillance apparatus that now surrounds all of us, built under our noses (and using our noses) by tech companies, law enforcement, commercial interests, and a secretive array of data brokers and other third parties.

In 2019, facial recognition may have finally graduated from dystopian underdog — it was only the fourth- or fifth-most-frightening thing in Minority Report; it’s never played more than a supporting role on Black Mirror; and in the Terminator movies, it was a crucial safety feature preventing the Terminator from terminating the wrong people — to full-grown modern worry.

A brief recap of the year of Face Panic:

This spring, we heard that the FBI’s facial recognition database now includes more than 641 million images and the identities of an unsuspecting majority of Americans, which can be searched anytime without warrant or probable cause.

We also heard that spooked lawmakers banned police use of facial recognition in Oakland; Berkeley; Somerville, Massachusetts; and San Francisco, of all places, where Orwellian tech products are the hometown industry.

But everywhere else and in all other contexts, facial recognition is legal and almost completely unregulated — and we heard that it’s already being used on us in city streets, airports, retail stores, restaurants, hotels, sporting events, churches, and presumably lots of other places we just don’t know about.

Over the summer, we heard a rumor about a novelty photo app that might be a secret ploy by the Russian government to harvest our selfies for its own facial recognition database. That turned out to be false (or at least we think so), but it might’ve made us reconsider all the photos we’ve given to other companies whose loophole-filled terms of use agreements translate to “we own your face” — including Facebook, which is thought to have one of the world’s largest facial recognition databases and has not exactly proven itself to be the most responsible custodian of our private information.

We barely heard about the Commercial Facial Recognition Privacy Act of 2019, a bill introduced in March by Republican Senator Roy Blunt and Democrat Brian Schatz that would have prohibited companies from using facial recognition to track you in public, and collect or sell your face data, without your consent. It was the kind of common-sense bipartisan proposal that almost everybody can agree with; it was referred to a committee and never made it to a vote.

But we heard a lot about facial recognition’s unreliability, and that misidentifications are common, especially for people of color, and that the London Metropolitan Police’s system has an appalling failure rate, and that Amazon’s software once mistook a bunch of seemingly upstanding congresspeople for criminal suspects. Maybe that meant, we hoped, that the technology was still only half-baked and that our worries were premature, and that one big lawsuit could make it all go away.

And then we heard about Larry Griffin II. And if his story was meant to calm any fears about facial recognition, well, mission not necessarily accomplished. If the software works well enough to identify one bomb-hoax suspect among 8.4 million New Yorkers in under an hour using only a couple of grainy surveillance photos, maybe our worries aren’t so premature after all. Because even though facial recognition isn’t fully reliable yet, and it might never be, it’s already transforming law enforcement. And it probably won’t need to be perfect before it transforms our everyday lives, too.

In a possibly related story, perhaps you have noticed an unusually high demand for pictures of your face over the past several years?

Computerized facial recognition has been in development since the 1960s. Progress was steady but slow, though, until the recent arrival of advanced artificial neural networks — i.e., computer systems modeled on animal brains that can recognize patterns by processing examples — which have allowed human programmers to feed these networks many photos of faces and then step aside while algorithms teach themselves what faces look like and then how to tell those faces apart and eventually how to decide if a face in one photo is the same face in a different photo, even if that face is wearing sunglasses or makeup or a mustache or is poorly lit or slightly blurry in one image but not the other. The more photos an algorithm has to learn from — millions or billions, ideally — the more accurate it becomes.

Some companies asked you to upload your vacation photos and tag yourself in them. And others asked for a selfie in exchange for an autogenerated cartoon caricature of you or to tell you which celebrity or Renaissance painting you most resemble. And then some companies got impatient with all this asking, so they acquired the other companies that had already collected your photos, or they scraped public images of you from social media and dating sites, or they set up hidden cameras in public spaces to take their own pictures.

How many algorithms have been trained on your face? Hard to say, because there aren’t really any laws requiring your consent, but Facebook, Google, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, IBM, and dozens of start-ups with names like Facefirst, FaceX, and Trueface all have their own facial-recognition algorithms, and they had to have learned somewhere.

Some of those algorithms are pretty accurate, too, at least under optimal conditions. Last year, the U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) tested 127 facial-recognition algorithms from 40 developers to see how often they could find matches in a large database. With high-quality images to compare, the top-performing algorithms only failed to return the correct match in 0.2 percent of searches, which is 20 times better than the results of a similar test in 2014.

Facial recognition will inevitably improve on its own, but it might be even more accurate when used in combination with other long-range biometrics. In China, gait recognition is already identifying people based on the way they walk, with 94 percent accuracy according to one company offering the service. And the Pentagon claims to have developed a heartbeat laser — that is, an infrared beam that can read a person’s unique cardiac signature through a shirt or jacket, allegedly with 95 percent accuracy. (The current model can reportedly detect a heartbeat from 200 meters away, but with a slightly better laser, however: “I don’t want to say you could do it from space,” a Pentagon source told the MIT Technology Review, “but longer ranges should be possible.”)

For facial-recognition software to recognize you in the wild, it needs to be connected to a database with your photo and identifying information in it. (Just because an algorithm has trained with your face doesn’t mean it knows who you are.) Unless you’re Elena Ferrante or a member of Daft Punk, and maybe even if you are them, there’s a good chance you’re in a database or two.

If you’ve ever been tagged in a photo on Facebook or Instagram, for example, you belong to what is by Facebook’s own claims the world’s largest facial-recognition database, to which users add hundreds of millions of new images every day. The company’s facial-recognition algorithm, DeepFace, which is constantly retraining itself on those new images, is presumed to be more accurate than software used by most law-enforcement agencies.

For now, Facebook says it only uses DeepFace to suggest tags when users upload new pictures. But that didn’t help the company in August when a federal appeals court ruled that 7 million Facebook users in Illinois can sue the company for storing their face data without permission, which they claim is a violation of the state’s Biometric Information Privacy Act, currently the only such law in the U.S., which could make Facebook liable for as much as $5,000 per affected user or $35 billion total. (In response, Facebook has stopped suggesting tags for photos by default.)

The FBI’s facial-recognition database spans mug shots, the State Department’s entire directory of visa and passport pictures, and photos from the Departments of Motor Vehicles in at least 22 states (and counting) that allowed the agency to scan residents’ driver’s licenses without their consent. (In Utah, Vermont, and Washington, where undocumented immigrants can legally drive, DMVs have shared facial recognition data with Immigration and Customs Enforcement.) If you’ve managed to keep yourself out of the FBI’s database so far, that may get harder in October 2020, when Americans in 47 states will be required to show either a passport or a new federally compliant Real ID driver’s license to board any domestic flight.

All of this would be bothersome enough in a world with perfect data security or one in which you could get a new face as easily as your bank replaces a stolen debit card. But we live in neither of those worlds, and faces have already been hacked. In June, U.S. Customs and Border Protection announced that hackers had breached the servers of one of its subcontractors and stolen travelers’ face data, some of which reportedly turned up on the dark web.

Despite plenty of more deserving scandals, though, none caused as much hysteria in 2019 as FaceApp. In July, all of your friends, plus Snooki, the Jonas Brothers, and Lebron James, shared pictures taken with the image-processing tool, which went viral by making users look like elderly people. But panic ensued when they read FaceApp’s merciless terms of use agreement. (“You grant FaceApp a perpetual, irrevocable, nonexclusive, royalty-free, worldwide, fully-paid, transferable sub-licensable license to use, reproduce, modify, adapt, publish, translate, create derivative works from, distribute, publicly perform and display your User Content and any name, username or likeness provided in connection with your User Content in all media formats and channels now known or later developed, without compensation to you.”) And then even more panic ensued when they found out FaceApp is headquartered in St. Petersburg, Russia. Had Vladimir Putin tricked America again, this time into handing over the elusive face data of its influencers?

No, or at least probably not. FaceApp denied that the company shares data with third parties, and claimed most user images are deleted within 48 hours, which seemed to stem fears. But if FaceApp did decide to pull up stakes and pivot to facial recognition, it would not be the first company like it to do so: The photo-management app EverRoll launched in 2012 and collected 13 billion images in which users had tagged themselves and their friends. EverRoll’s parent company, which recently renamed itself Paravision, discontinued the app in 2016 and used those images to train its facial recognition software, which is now ranked as the No. 3 most accurate algorithm tested by NIST and is sold to law enforcement.

The worst-case scenario for facial recognition might look like something like China’s forthcoming “social credit system.” When the system is fully operational next year, the government will use all surveillance methods at its disposal, including facial recognition and 200 million cameras, to track citizens’ behavior and assign each of them a social score, which will have a variety of consequences. Infractions such as jaywalking and buying too many video games could make it harder to rent an apartment or get a loan from a bank. That probably isn’t likely in the U.S., but a more ordinary kind of surveillance is almost inevitable. Maybe it’s already here.

Commercial facial recognition has been around for years, but since there aren’t any laws requiring anyone to disclose that they’re using it on you, it’s impossible to say how widespread it is. Which means any camera you pass could be recognizing your face.

Among the many vendors offering commercial facial recognition software is Face-Six, a Tel Aviv–based company founded by Moshe Greenshpan in 2012 after Skakash, a mobile app he was developing that would have identified actors in movies and TV shows, failed to attract investors. Greenshpan says he now serves more than 500 customers worldwide, offering a variety of custom products, including FA6 Retail (to prevent shoplifting), FA6 Class (to take attendance in schools), FA6 Med (for use in hospitals to verify patients identities and prevent treatment errors), and FA6 Drone (which “identifies criminals, missing people, and civilians from a drone’s camera,” and which is available “for government and private uses.”) But Greenshpan’s most controversial product has been Churchix, which he sells to churches that want to keep track of which parishioners are showing up to mass.

Churchix attracted negative coverage when it launched in 2015, some of which is linked to on the company’s website. “In the beginning, all press was good press,” says Greenshpan. “You really need to explain to people why facial recognition is more good than bad. Churches manage attendance manually, but when we provide an efficient tool that does it automatically, suddenly there are concerns.” And if those concerns include transparency? “We don’t know what each and every customer does with our software,” Greenshpan says, “but usually churches [that use Churchix] don’t tell their members.”

But Greenshpan does connect me with David Weil, founder of the Warehouse, an after-school recreation center and skateboarding park in Bloomington, Indiana, which uses Face-Six’s software on two security cameras, for one extremely specific purpose: “Our building is five acres under one roof, and there are over 200 registered sexual offenders in the area,” says Weil. “So with that much space and that many pedophiles, this software really helped us.”

As visitors enter the building, the cameras scan their faces, and Face-Six’s software searches them against a database provided by the local sheriff’s office. According to Weil, the Warehouse had 72,000 visits in 2018, and facial recognition managed to keep out two sex offenders: “We just politely told them, ‘We’re a youth center. You’re not allowed to be here,’” he says. “I had one false ID, but the gentleman was very understanding of the situation.”

Among the other ways we know facial recognition is already being deployed:

Airlines are using it to replace boarding passes, and the Department of Homeland Security says it plans to use facial recognition on 97 percent of airline passengers by 2022.

And at least three arenas have experimented with the technology, including Madison Square Garden.

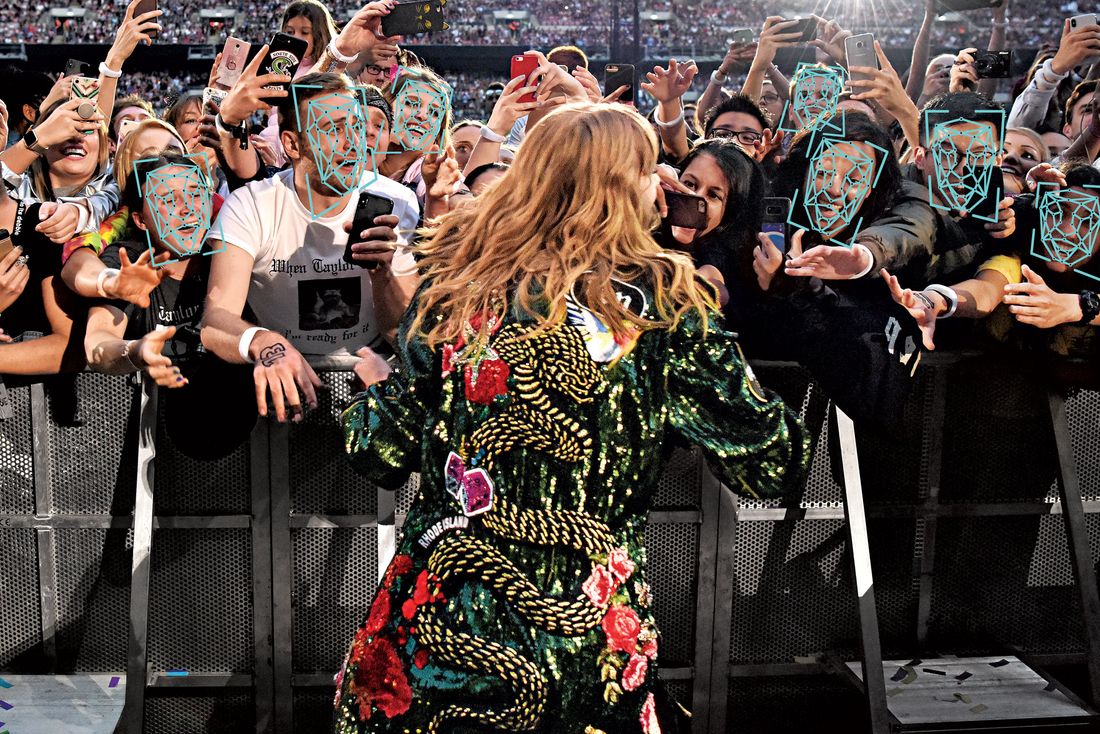

On stops of Taylor Swift’s recent Reputation tour, fans’ faces were scanned and searched against a database of her hundreds of known stalkers.

Last year, residents of an apartment complex in Brownsville protested when they found out their landlord wanted to use facial recognition to supplement their key fobs — but other buildings in the city have been known to use it for years, including the 12 that make up the Knickerbocker Village complex on the Lower East Side. Some virtual-doorman systems include it, too.

At least eight public-school districts in the U.S. have installed facial-recognition systems to detect suspended students and anyone else banned from school grounds.

Retailers use facial recognition to prevent theft, and some software even comes bundled with databases of known shoplifters, but not many stores will admit to it. Last year, the ACLU asked 20 top retail chains whether they use facial recognition, including Best Buy, Costco, Target, and Walmart, and only received two answers — rom the grocery conglomerate Ahold Delhaize, whose brands include Food Lion and Stop & Shop, which doesn’t use it, and from the hardware chain Lowe’s, which tested facial recognition in the past but has since stopped.

Retailers don’t need to run facial-recognition software on their premises to benefit from it. Apple denies using the technology in its brick-and-mortar locations, but in one confusing incident last year, a New York teenager was arrested and charged with stealing from multiple Apple Stores when police said he was identified by facial recognition. Apple apparently employs an outside firm called Security Industry Specialists in some locations; SIS may have run facial-recognition software on surveillance footage captured inside the Apple Stores the teen was alleged to have stolen from. (Charges were dropped against him when an NYPD detective realized he looked nothing like the suspect in the footage of the robberies. In April, the teen sued Apple and SIS for $1 billion.)

Facial recognition could soon be more valuable to retailers in other ways. One likely possibility is that some will eliminate checkout lines by having customers pay with their faces. Another is using facial recognition to target the people most likely to buy things by tracking their in-person shopping habits the same way cookies track our online ones — or maybe, eventually, using what they know about our virtual selves to direct us toward products in the real world. If you’ve ever been creeped out by an uncannily well-targeted ad served to you on Facebook or Instagram, imagine being helped by a retail employee who knows what’s in your web history.

But what if you’re not the person facial recognition says you are? Last year, the ACLU used Amazon’s facial recognition software, Rekognition, to search a database of 25,000 mug shots using photos of members of Congress and found that it misidentified 28 lawmakers as criminals, including six members of the Congressional Black Caucus, and a similar test this summer mistook 26 California state legislators, again with people of color overrepresented in the false matches.

Amazon says the ACLU intentionally misrepresented its software by setting its confidence threshold too low — the company recommends that police act only on matches in which the system expresses at least 99 percent confidence — but there’s nothing to prevent police from doing the same thing. “It’s toothless,” says Jacob Snow, the technology-and-civil-liberties attorney at the ACLU who ran the tests. “Amazon could say to law enforcement, ‘We’re going to set the confidence threshold at 99 percent, and you can’t change it.’ But they’re not doing that.”

Dark skin isn’t the only thing facial recognition fails with. In NIST’s tests, it found that even top-performing algorithms had trouble identifying photos of the same person at different ages and were often unable to tell the difference between twins — not just identical twins but fraternal ones of the same sex, too. And performance depends on the clarity of the photos being used. NIST was primarily comparing high-quality mug shots to other high-quality mug shots, but under real-world conditions, with blurry surveillance photos taken at bad angles by cameras that may have been set up incorrectly, results may vary.

Even a facial-recognition system with low error rates can cause problems when deployed at large scale. During six recent tests of the London police’s facial-recognition system, which scanned the faces of people on public streets in search of wanted suspects, 42 matches were made but only eight were verified to be correct (30 matches were eventually confirmed to be misidentifications, and four of the 42 people disappeared into crowds before officers were able to make contact). Because they scanned thousands of faces in total, the London police said their error rate was 0.1 percent, but most headlines begged to differ: LONDON POLICE FACIAL RECOGNITION FAILS 80% OF THE TIME AND MUST STOP NOW, said one.

Police have also been caught taking creative license with the technology. A report published in May by the Georgetown University’s Center on Privacy and Technology found that six departments in the U.S. allow officers to run composite sketches of suspects through facial-recognition software. That same report tells the story of a suspect who’d been caught by surveillance cameras allegedly stealing beer from a CVS in Gramercy Park in 2017, but the video was low quality and no useful matches were returned. A detective noticed, though, that the man bore a resemblance to Woody Harrelson, so he ran a search using an image of the actor — which eventually led to an arrest. “The person they ended up investigating was the tenth person on the candidate list,” says Georgetown Law’s Clare Garvie, the author of the report, “meaning the algorithm thought nine other people [in the NYPD’s mug-shot database] looked more like Woody Harrelson. If you can put person A into an algorithm and find person B, why does that not prove that if you’re looking for looking for person B, you might accidentally find person A? They intentionally forced a misidentification as a valid investigative technique.”

NYPD spokesperson Devora Kaye notes that this case was “just one of more than 5,300 requests” to FIS in 2017. The NYPD, she says, only uses facial recognition as an investigative tool and doesn’t arrest or detain suspects whose identities haven’t been corroborated by other means. “A facial recognition match is a lead. No one has ever been arrested solely on the basis of a computer match, no matter how compelling.”

If Larry Griffin II’s story typifies a best-case use of facial recognition for law enforcement, Kaitlin Jackson, a public defense attorney with the Bronx Defenders, tells me one that exposes its drawbacks. Jackson represented a man who’d been arrested for the theft of socks from a T.J. Maxx store in February 2018, supposedly after brandishing a box cutter at a security guard. “My client was picked up months after the robbery, and the only way I even found out facial recognition was used was that I just started calling the prosecutor and saying, ‘How in the world did you decide months after that it was my client? There are no forensics,’” she says. “It turned out the police went to T.J. Maxx security and said, ‘We want to pull the surveillance [video], we’re going to run it through facial recognition’ — so they were already cluing him in that any suspect will have been picked by facial recognition. And then they texted the security guard a single photo that he knows has been run through facial recognition, and they said, ‘Is this the person?’ That’s the most suggestive procedure you could possibly imagine. And then they make the arrest and say it’s on the basis of an [eyewitness] ID, and they try to bury that this is a facial-recognition case.” (The NYPD said the defendant had committed a theft at the same store before and said the security guard knew him “from prior interactions.” The detective on the case showed him an image hoping it would “put a name to a face,” the department said in a legal filing.)

Jackson’s client had at least two lines of defense: He has a twin brother, who could have triggered the facial-recognition match — although Jackson doesn’t think the twin stole any socks either — but more important, his wife was in labor at the time of the theft and he was in the delivery room. “We had pictures of them at the hospital, and his name was on the birth certificate,” says Jackson. But the prosecution would not dismiss the case — partly, she suspects, because they have an “undying faith that the software doesn’t get it wrong.” Their only recourse, she said, would be to argue, “Maybe he left a few minutes before his baby was delivered and ran out to get socks and then came back.”

Jackson says her client spent half of last year in prison. “He was on probation when he was arrested. So our real problem was the way that all these systems interact. Probation lodged a hold, and they would not withdraw the hold because of this case, and the prosecution wouldn’t dismiss this case. And then finally [the prosecution] offered him something that would get him out of jail. So he did what a lot of us would — he took a plea of something he did not do.”

But facial recognition is about more than just who you are, and what you’ve bought, and the crimes you have or haven’t committed, and whether your resemblance to a sex offender will make it hard to find places to skateboard — it’s also about how you feel. Because another thing the technology can do, or at least supposedly do, is detect emotions.

Amazon, IBM, Microsoft, and others claim their software can guess which emotion you’re feeling based on your facial expressions — or in some cases microexpressions, under the logic that even if you attempt to hide your feelings, certain facial muscles are beyond your control. Amazon, for example, says Rekognition can infer whether a face is expressing happiness, sadness, anger, confusion, disgust, surprise, calmness, or fear — although the documentation warns that results “are not a determination of a person’s internal emotional state and should not be used in such a way,” and that “a person pretending to have a sad face might not be sad emotionally.”

Other vendors are more confident in their mood-reading abilities. The London-based start-up RealEyes markets a service to advertisers that scans people’s faces through their computers’ webcams to measure their attention level and emotions while they watch commercials. The Utah-based company Hirevue claims its software can analyze video job interviews to judge personality traits and eliminate disinterested candidates. (Hirevue’s clients include Dunkin’ Donuts, Staples, and Urban Outfitters.)

On its website, the facial-recognition company Kairos brags about the work it did for Legendary Pictures gauging reactions of audience members at movie test screenings: “More than 450,000 emotional measurements were recorded per minute over the screening of preview films, for a total of around 100 million facial measurements processed in total.” Kairos says Legendary used that data to determine which parts of movies worked best in ads, identify “the demographics most likely to share trailers,” and ensure Legendary’s movies were “appealing to mainstream audiences as well as their targeted fan demographic.” Neither Kairos nor Legendary Pictures would confirm which movies were involved, but Kairos CEO Melissa Doval says the screenings probably happened in 2013 or 2014, and there’s a picture from the 2013 Superman movie Man of Steel on Kairos’ website.

Your facial tics may not necessarily lose you any jobs or give the wrong impression about your taste in superhero movies, though — because emotion-detection software might not really work. In July, a group of five top psychologists published a report in Psychological Science in the Public Interest, which cited over 1,000 other journal articles and found that facial expressions are more complex than the software gives them credit for: “It is not possible to confidently infer happiness from a smile, anger from a scowl or sadness from a frown, as much of current technology tries to do when applying what are mistakenly believed to be the scientific facts.”

Ultimately, the most worrisome thing about facial recognition might be how accessible it is. Because it’s not just available to governments and corporations—it’s also for sale to you, me, your landlord, random perverts, and anyone else with a camera and a computer, and for cheaper than you’d probably expect: Amazon’s Rekognition, for example, offers a free year-long trial that lets you identify faces in 5,000 images or 1,000 minutes of video per month (and after that, it’s a penny per ten photos or ten cents per minute of video).

If none of the off-the-shelf software packages suit your particular needs, it turns out it’s pretty easy, if you know what you’re doing, to roll your own facial-recognition app using freely available open-source code. I watched one YouTube tutorial in which a programmer built his own facial-recognition system that could distinguish between his face and the cast of Game of Thrones.

It’s not hard to imagine more sinister applications. This spring, a developer claimed on Chinese social media that he’d used facial recognition and publicly available photos from Facebook and Instagram to identify 100,000 women in amateur porn videos. He didn’t share any proof and may have been lying — but given all the other seemingly unbelievable things about facial recognition we now know to be true, maybe he wasn’t.

I wanted to experiment myself, so I bought a Tend Insights Lynx Indoor 2, a tiny and cheap but well-reviewed home security camera that comes bundled with its own facial-recognition software. It worked well for what it did, which in my case wasn’t much: I set the camera on my desk, connected it to my Wi-Fi network, downloaded the companion iPhone app, and uploaded a picture of myself so it knew what I looked like. I left my apartment, and in a few minutes when I came back, the Lynx sent a push notification to my phone to tell me I was home, along with a short video for proof. That may not sound like $60 well spent, but it was a small price for a feeling of control I might never have again: After the inaugural test of my home facial-recognition system, I unplugged it and stuffed it in a drawer.

*This article appears in the November 11, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!