Psalms is one of the most-often quoted books in the New Testament. Psalm 110, in fact, is the most alluded-to passage in the New Testament. (The other two books quoted most often are Deuteronomy and Isaiah.)

For Mormons, Psalms is one of those many books we have a strong tradition… of ignoring. Yet, said President Benson, “The psalms in the Old Testament have a special food for the soul of one in distress.”

Psalms are often prayers, songs, or both. They praise, ask, censure, worship, question, and plead. Are you angry at God? So are some of the Psalms. Are you frustrated at how the wicked seem to prosper, and your own efforts at “living right” seem fruitlessly pointless? There are Psalms expressing this frustration to God. Are you depressed? There are Psalms for that. I think Psalms is a vastly underused pastoral resource, because we don’t know them. If I were a Bishop, during the OT year, I think I’d assign “talks” that included reading one or two thematic Psalms over the pulpit every Sunday, probably in a non-KJV translation.

Psalms as poetry

As with any genre, understanding its conventions will help you at least appreciate its artistry.

The main thing to understand about Hebrew and other ancient Near Eastern poetry is that its primary building block is not assonance or rhyme, but parallelism and repetition of various kinds. While not all the parallelism present translates well or at all, semantic parallelism most definitely comes through in translation. That is, you say X, then you repeat X with a term that means roughly the same thing, e.g. line 1 will say “my brother” and line 2 will say “my mother’s son” referring to the same guy.

You will best understand and appreciate the poetry of Psalms in a translation newer than the KJV (although sometimes it captures things quite well.) Robert Alter, who is a professor of literature and Hebrew, has a translation and commentary on Psalms- The Book of Psalms: A Translation with Commentary, but any newish Bible translation that I recommend will be useful: Jewish translation, NRSV, etc.

The best place to start getting a handle on the nature of the poetry is

- Kevin Barney’s award-winning Ensign article on Understanding Old Testament Poetry. (LDS.org link, PDF.) As a side note, I wish the Ensign still did things like this, both in terms of holding article contests and this kind of scriptural depth.

- See also his article on poetic word pairs from The Maxwell Institute. Link

- For follow-up, here is the Anchor Bible Dictionary article on parallelism (pdf).

- A handout I made for my Psalms Institute class (pdf)

- And there’s a section of my Sperry Symposium screencast on Reading the Old Testament in Context that talks about poetry.

In terms of books, here’s what I’d recommend.

- Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Poetry

- James Kugel, The Idea of Biblical Poetry: Parallelism and Its History

- And for the advanced student looking to dig, no Hebrew is necessary but it’s helpful. Adele Berlin, The Dynamics of Biblical Parallelism

This is what we were assigned in Hebrew class at the University of Chicago. Berlin is the author of the ABD article above.

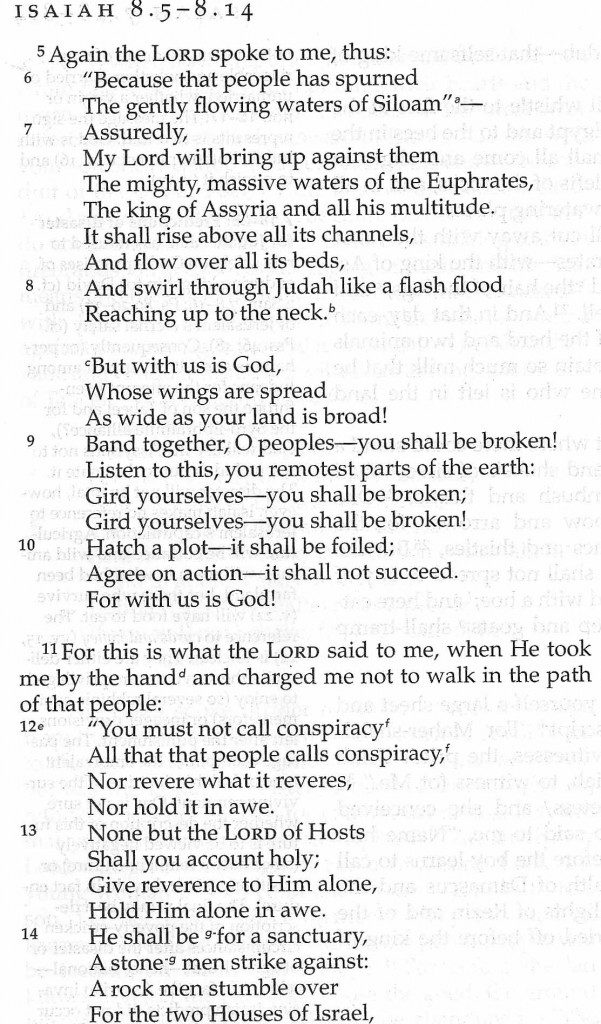

Our KJV does not set off poetry at all or indicate where the prose changes to poetry, but the vast majority of prophesy is delivered as poetry. Isaiah, Jeremiah, Amos, etc., are nearly entirely poetry. Most Bible translations today will do something like set off the parallel lines to indicate a poetic section, as in the Isaiah passage below from the JPS Translation (found in the Jewish Study Bible.) Note the differences between the prose of v.5 and 11, verses the poetic parallel lines in the rest.

Psalms as Israelite hymnbook

In my classes, I have often related different portions of the Old Testament to various LDS books, as the analogy helps us understand their role and function. Samuel-Kings is kind of like History of the Church. Leviticus and large portions of Numbers and Deuteronomy are a bit like the CHI or other Church handbooks, with detailed instructions on policies, laws, and how to perform various ordinances and under what circumstances. Important, but not terribly exciting to read through.

Psalms is very much like the LDS Hymnbook. How so?

- The songs/Psalms represent a selection of what existed previously in oral form, and written second.

- The contents were written at different times by different people

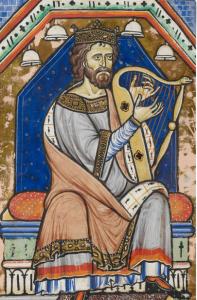

- Frequent attribution to King David, but see headings.

- Psalms 42-49 attributed to sons of Korah.

- They’re divided into sections

- In our hymnbook, these are thematic divisions.

- In Psalms, there are five divisions, with no apparent overriding theme. 1-41; 42-72; 73-89; 90-106; 107-150. Each group ends with small doxology or statement of praise to God.

- Some hymns are foreign, and have been borrowed with more or less adaptation.

- We have lots of hymns written by Protestants, sometimes translated from German.

- Psalm 29 is traditionally thought to have been lifted fairly directly from a Canaanite hymn to Baal, and the name changed. Psalm 104 comes fairly directly from an Egyptian hymn to the sun.

- Paying attention to the lyrics/themes, there are some odd things, inconsistent, sometimes doctrinally at variance, present by nature of being archaic or borrowed or attributed.

- For example, How Firm a Foundation says “What more can he say than to you he hath said?” Um, God has no more to say or reveal, really? What about line-upon-line? What about God “will yet reveal many great and important things pertaining to the Kingdom of God”? It’s not a very LDS line.

- Psalm 82 portrays a council of divine beings. Psalm 93 hints strongly at a third creation account.

- Contrast innocence of David in Psa 18 with Psa 51. Both are supposedly David.

- Modifications over time to make them more comfortable/”orthodox”/keep with with cultural sensitivities.

- I am a Child of God has been changed recently to emphasize doing over knowing, in the line “teach me all that I must

knowdo to live with him some day”- For a long article looking at many of these changes to the hymnbook, see “Changes in LDS Hymns” in Dialogue. (PDF link)

- Psalm 96 incorporates part of Psalm 29, but changes “gods/sons of the gods/divine beings” in 29:1 (KJV “mighty”) to the more monotheistic “families of the nations” in 96:7-8. Briefly on monotheism in the Old Testament, see here from Bible Review.

- I am a Child of God has been changed recently to emphasize doing over knowing, in the line “teach me all that I must

- Some are performed on various occasions or rituals

- We have hymns for sacrament, easter, Christmas, New Year, but also patriotic/nationalistic hymns.

- Matt 26:30 records that after the Last Supper, before they leave for the mount of Olives, they sang a hymn. As it turns out, we know what that was. Psalms 113-118 were called the Hallel, “praise!” (like hallelu-yah, the plural command “all you praise Yahweh!). The Hallel was traditionally sung at Passover… as the Last Supper has been portrayed (though the Gospels disagree on this.)

- Performed by individuals, groups, choir.

- Levitical choir in temple, 2Chr 5:13. Included women? 1Chr 25:5, Ezr 2:65

- Songs of ascent sung by Israelite pilgrims as they ascended to Jerusalem in Psalms 120-34.

- Repetition

- Abide with Me exists as both 165 and 166. Or repeated tunes with Brightly Beams our Father’s Mercy also appaearing as Should You Feel Inclined to Censure.

- Psalm 53 and 14 are almost identical. Only the names of Yahweh and Elohim switched. To the Israelites, this would have been minor, just parallel names.

Recommended Books

Beyond the books above, any newer Bible translations will be more sensitive to poetry than the KJV, at least in terms of recognizing it and setting it off somehow to tell you what you’re reading is now poetry.

- Nahum Sarna, On the Book of Psalms: Exploring the Prayers of Ancient Israel

- Sarna is a Rabbi/PhD author I quite like.

- When it comes to the NT and its quotations, this is a useful volume. Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament

Like several books above, it’s available for Logos as well as paper.

As always, you can help me pay my tuition here. You can also get updates by email whenever a post goes up (subscription box on the right). You can also follow Benjamin the Scribe on Facebook.