After a rare uterine cancer diagnosis at age 26, she gave birth to a baby boy

Whitney Everard thought she was just having a really bad period. But when the nonstop bleeding continued for months, even after the 26-year-old switched birth control methods, she returned to her OB-GYN. Concerned, her doctor ran more tests, including an ultrasound.

"Having your period once a month gets old, but having it continuously for three to four months was stressful," she said.

When the ultrasound revealed a mass on her uterus, Everard was referred to an oncologist who performed a biopsy. The results were shocking: Everard had a rare uterine cancer that impacts 1 in 1 million women. The only treatment for it is a hysterectomy, meaning Everard would not be able to carry children. It was a sobering reality.

“There were times when I was angry and there were times when I was just frustrated and every emotion,” Everard, now 28, of Carlsville, Wisconsin, told TODAY.

When the treatment doesn’t fit

Approximately 3% of women will be diagnosed with uterine cancer at some point in their lifetime, according to the National Cancer Institute. The most common type of uterine cancer is called endometrial cancer, where malignant cells form in the lining of the uterus. A woman's risk increases with age: Most cases of endometrial cancer are diagnosed in women ages 45-74.

When doctors first spotted Everard’s tumor in the fall of 2018, they noticed it was nestled in the muscle, what’s known as uterine sarcoma, a rare type of uterine cancer. The sarcoma was an endometrial stromal sarcoma, which makes up fewer than 0.2% of uterine cancers, according to Dr. Erin E. Stevens, a gynecological oncologist at Prevea Health in Green Bay, Wisconsin. It mostly affects women in their 40s and 50s, and doctors perform a hysterectomy (surgery to remove a woman's uterus) to stop the cancer from spreading.

“They are much more rare than the typical uterine cancers,” Stevens told TODAY. “There's no way to get to that mass without removing it (the uterus).”

But Everard wanted to have children and treatment would make her dreams impossible. So she started looking for research on younger women with uterine cancer or women with uterine cancer who didn’t have a hysterectomy. She found very little information.

“There was nothing saying what would happen if I did eventually get pregnant,” she said. “It was frustrating because of the lack of information, or information stating the only treatment option is a hysterectomy. But they don't know what will happen if I don't have it.”

While Stevens recommended a hysterectomy and advised Everard to get a second opinion, she wanted to work with Everard so she felt comfortable with a treatment plan that would accommodate her reproductive goals.

Health & Wellness

“She just wanted to know what was possible,” Stevens said. “She really understood what was best for her.”

While less is known about this type of uterine cancer, experts understand that estrogen makes it flourish. This helped Stevens create an alternative treatment plan, avoiding a hysterectomy. She would remove the tumor and after surgery, Everard would take progesterone for four to six months. Theoretically, the progesterone would stop the estrogen from feeding any lingering cancer cells.

After she completed the hormone therapy, Everard and her boyfriend, Nathan Bittorf, could try conceiving.

“I really felt like Dr. Stevens was on my side,” Everard said. “I didn’t want lose the opportunity to have a child because no one knew what would happen.”

The uncertainty was unsettling at times.

“We were going into this knowing there are a few case reports saying that this has worked in the past,” Stevens explained. “And maybe a couple of others that said that it has not worked.”

A baby and good health

Everard completed the hormone therapy in the spring. In June 2019, Everard visited Stevens for a follow-up appointment. The doctor wanted to do a biopsy to make sure the cancer hadn’t returned. Everard asked her to wait; she thought she might be pregnant and her instinct was right.

“We were really lucky that it didn’t take us long,” she said.

The pregnancy was uneventful, but her doctors still worried. During pregnancy, hormones increase and that could cause the cancer to return.

“Your estrogen and progesterone levels are sky high and there was this theoretical risk that if there was a cell left behind, it would grow because it was going to be stimulated by the hormones,” Stevens said.

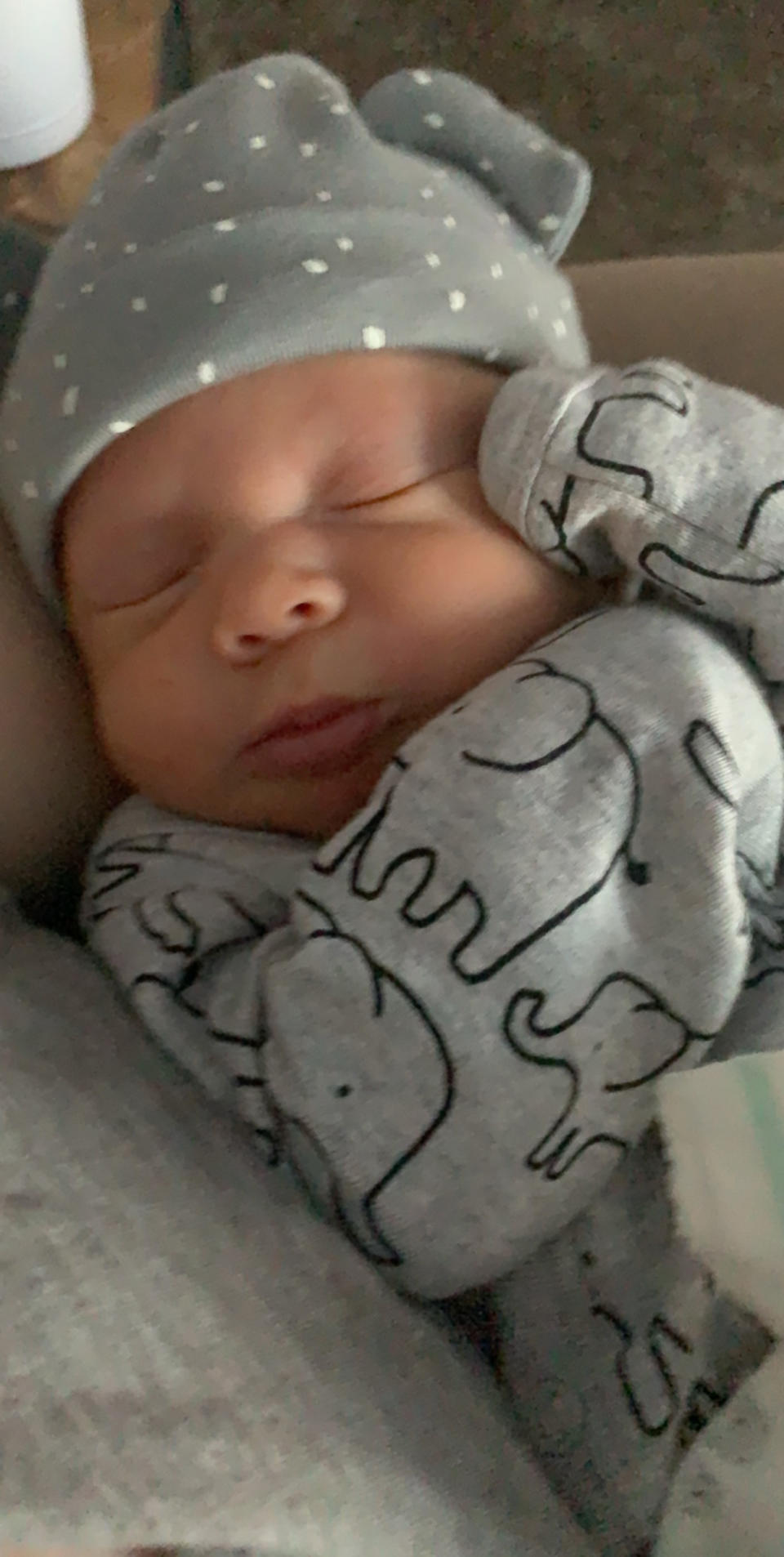

But on February 6, 2020, Everard delivered a healthy baby boy, William Lloyd Bittorf. Stevens was there and discovered an additional piece of good news: Everard was cancer-free.

“That's better than any imaging study that I can do,” Stevens said.

Everard is enjoying motherhood, and while she wants to have another biological child, she knows she’ll have a hysterectomy soon to prevent the cancer from returning. She is sharing her story to help other women with similar cancers.

“I was 26 years old and I was told that I might never be able to have kids,” she said. “If I would have had a full hysterectomy, I would have regretted it. Be an advocate for yourself and make sure that you're making the decisions that are best for you.”