Doctors have used a brain-reading device to hold simple conversations with “locked-in” patients in work that promises to transform the lives of people who are too disabled to communicate.

The groundbreaking technology allows the paralysed patients – who have not been able to speak for years – to answer “yes” or “no” to questions by detecting telltale patterns in their brain activity.

Three women and one man, aged 24 to 76, were trained to use the system more than a year after they were diagnosed with completely locked-in syndrome, or CLIS. The condition was brought on by amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, a progressive neurodegenerative disease which leaves people totally paralysed but still aware and able to think.

“It’s the first sign that completely locked-in syndrome may be abolished forever, because with all of these patients, we can now ask them the most critical questions in life,” said Niels Birbaumer, a neuroscientist who led the research at the University of Tübingen.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to establish reliable communication with these patients and I think that is important for them and their families,” he added. “I can say that after 30 years of trying to achieve this, it was one of the most satisfying moments of my life when it worked.”

All of the patients, who are fed through tubes and kept alive on ventilators, are cared for at home by family members. To train the patients on the system, doctors asked them to think “yes” or “no” in response to a series of simple questions, such as “Your husband’s name is Joachim” and “Berlin is the capital of France.”

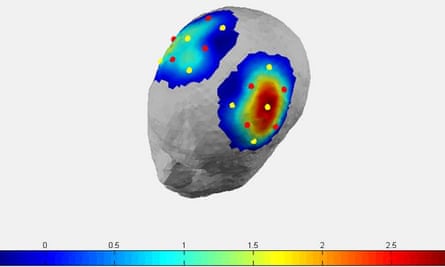

During the sessions, the patients wore a cap that uses infrared light to spot variations in blood flow in different regions of the brain. As they answered the questions, a computer hooked up to the cap learned to distinguish the blood flow patterns for “yes” and “no” in each patient.

When the patients scored at least 70% on the training questions, the doctors moved on to more personal questions. The most important of these were about quality of life. Perhaps unexpectedly, all four patients indicated that they were “happy” with life, suggesting that locked-in syndrome might not be the living hell many presume it to be.

But while the renewed ability to communicate with the world was a boon for the patients and their carers, not all of the answers went down well. One patient was a 61-year-old man whose 26-year-old daughter asked whether she should marry her boyfriend, “Mario”. Her father said “no” nine times out of ten. “She went ahead anyway,” Birbaumer told the Guardian. He did not ask if she regretted ever posing the question.

The findings, reported in the journal Plos Biology, do not mean that all locked-in patients are content with their lives. The four patients involved in the study had all chosen to be kept alive on a ventilator once their own breathing had failed, a decision that suggested they did not wish to die. Only a small percentage of CLIS patients who are moved on to ventilators survive the transition. “We have never had a patient who survived outside family care,” Birbaumer said.

But patients with locked-in syndrome have reported a good quality of life before, even matching that of healthy people of the same age. Birbaumer said the reasons are unclear, but he wonders if patients become focused on the good social interactions around them, and even experience something akin to a state of meditation because they cannot feel or move their bodies. “We find that they see life in a more positive way,” he said.

For his next project, Birbaumer wants to build a system that allows patients to communicate more proactively, rather than simply answer questions. In the 1990s, the French journalist, Jean-Dominique Bauby, who became locked-in after a massive stroke, dictated his bestselling memoir, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, by blinking his left eye to select letters from the alphabet. Birbaumer believes a system that reads brain activity could achieve the same ends for completely locked-in patients who cannot even move their eyelids.

Adrian Owen, a neuroscientist at the University of Western Ontario, has been exploring whether the same technology, known as functional near-infrared spectroscopy, or fNIRS, can be used to communicate with other kinds of brain-injured patients, including those who are presumed to be in a vegetative state. “The results of this study suggest that we are on the right track,” he said.

“Finding a portable, cost-effective and reliable means for communicating with patients who are entirely physically non-responsive is the holy grail for those of us working in this field. If these findings can be replicated in a larger group of patients they suggest that fNIRS may be the answer.

“One of the most surprising outcomes of this study is that these patients reported being ‘happy’ despite being physically locked-in and incapable of expressing themselves on a day-to-day basis, suggesting that our preconceived notions about what we might think if the worst was to happen are false. Indeed, previous research has shown that most locked-in patients are actually reasonably satisfied with their quality of life,” he added.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion