Only a few drugmakers even try to fight superbugs — a growing threat

A dependence on only a few pharmaceutical companies to sustain the fight against superbugs is putting the world in a precarious position, a new report shows.

Progress in tackling drug-resistant infections isn’t keeping pace with the rising threat, according to the latest Antimicrobial Resistance Benchmark, published Tuesday by the Access to Medicine Foundation. The pipeline of new antibiotics in advanced tests remains too small, the nonprofit found.

News from the field is grim as low profits discourage investment in crucial antibiotics. Since the group’s last report in 2018, two major players, Novartis and Sanofi, have retreated from antibiotic research as the pharma industry shifts toward lucrative areas such as cancer. And two smaller drug developers, Achaogen Inc. and Melinta Therapeutics, have filed for bankruptcy.

“We don’t have the luxury now to have another one of these few companies leaving antibiotic development,” said Jayasree Iyer, executive director of the Netherlands foundation. The lineup of experimental products, Iyer said, is “extremely fragile.”

The study, released at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, also cited signs of progress, with some drug companies boosting efforts to discourage the overselling of current antibiotics and sharing more data on where drug resistance is emerging.

GlaxoSmithKline has the biggest batch of potential products, developing almost one-fifth of all the research and development projects the group identified, according to the benchmark. The report also cited Pfizer Inc., Johnson & Johnson, Entasis Therapeutics Holdings Inc. and Cipla Ltd. as some of the other leaders in the field.

Only 51 drug candidates are in advanced development to treat bacterial and fungal infections, and few of those are truly novel, according to the report. At least 40 projects are no longer in the pipeline. Studies suggest about nine out of 10 potential drugs fail to make it through human testing.

A separate report last week found that research and development spending for a group of 15 companies fell to $1.2 billion in 2018 from $1.9 billion two years earlier. The research, from the AMR Industry Alliance, raises concern about a shortfall in late-stage spending in particular.

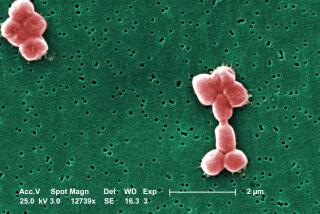

The need for new antibiotics is rising along with the risks. About 700,000 people worldwide die annually as a result of superbugs, and by 2050 that number could explode to 10 million if the problem remains unchecked.

But antibiotics revenues aren’t big enough for companies to recoup their research investment, and policies to encourage such activity haven’t yet made much of a difference. Sales of any new antibiotic remain low by design, as doctors wary of promoting resistance keep it as a medicine of last resort.

“This is not a situation where you need a scientific miracle,” Iyer said. “You need an economic solution.”

There are a number of efforts underway to fix a market seen as broken.

The U.K. said last year that it would test the world’s first “subscription-style” payment model. Paying upfront for access to drugs based on their usefulness to the National Health Service should reassure companies that they will be compensated even if a medicine is stored in reserve, the U.K. government said.

Without incentives and a turnaround in investment, the worst-case scenario is that “a whole industry can collapse,” said Aleks Engel, director of the Repair Impact Fund, launched two years ago by Novo Holdings in Denmark to invest in companies tackling antimicrobial resistance.

Yet some new private and government initiatives globally could provide a “few rays of sunshine” in the second half of the year, he said. “We do see escalating interest from several parties as to the crisis.”