The messages from Beijing to protesters in Hong Kong are increasingly ominous. First there was propaganda footage of Chinese soldiers garrisoned in Hong Kong drilling for intense urban fighting that looked more like a civil war than search and rescue or crowd control.

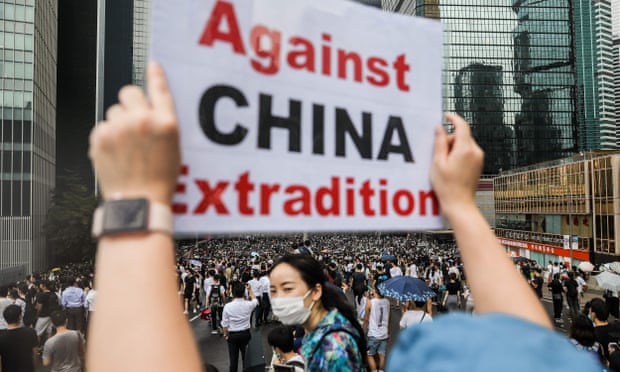

Now footage has emerged of armoured paramilitary vehicles massing across the border. Two months into demonstrations sparked by a controversial extradition law, official rhetoric from Beijing has escalated too. Authorities recently denounced protests as “terrorist acts”, promised an “iron fist” response and, perhaps most alarmingly, described the movement as a “colour revolution”.

China considered the pro-democracy protests which swept across the former Soviet Union during the early years of this century, most prominently Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution, to be existential threats to be tackled at almost any cost. Putting the same label on protesters implies Beijing will stop at little to crush the movement.

Quick GuideWhat are the Hong Kong protests about?

Show

Why are people protesting?

The protests were triggered by a controversial bill that would have allowed extraditions to mainland China, where the Communist party controls the courts, but have since evolved into a broader pro-democracy movement.

Public anger – fuelled by the aggressive tactics used by the police against demonstrators – has collided with years of frustration over worsening inequality and the cost of living in one of the world's most expensive, densely populated cities.

The protest movement was given fresh impetus on 21 July when gangs of men attacked protesters and commuters at a mass transit station – while authorities seemingly did little to intervene.

Underlying the movement is a push for full democracy in the city, whose leader is chosen by a committee dominated by a pro-Beijing establishment rather than by direct elections.

Protesters have vowed to keep their movement going until their core demands are met, such as the resignation of the city’s leader, Carrie Lam, an independent inquiry into police tactics, an amnesty for those arrested and a permanent withdrawal of the bill.

Lam announced on 4 September that she was withdrawing the bill.

Why were people so angry about the extradition bill?

Beijing’s influence over Hong Kong has grown in recent years, as activists have been jailed and pro-democracy lawmakers disqualified from running or holding office. Independent booksellers have disappeared from the city, before reappearing in mainland China facing charges.

Under the terms of the agreement by which the former British colony was returned to Chinese control in 1997, the semi-autonomous region was meant to maintain a “high degree of autonomy” through an independent judiciary, a free press and an open market economy, a framework known as “one country, two systems”.

The extradition bill was seen as an attempt to undermine this and to give Beijing the ability to try pro-democracy activists under the judicial system of the mainland.

How have the authorities responded?

Beijing has issued increasingly shrill condemnations but has left it to the city's semi-autonomous government to deal with the situation. Meanwhile police have violently clashed directly with protesters, repeatedly firing teargas and rubber bullets.

Beijing has ramped up its accusations that foreign countries are “fanning the fire” of unrest in the city. China’s top diplomat Yang Jiechi has ordered the US to “immediately stop interfering in Hong Kong affairs in any form”.

Lily Kuo and Guardian reporter in Hong Kong

The question many are now asking in Hong Kong is whether that might include Chinese troops in the city’s streets, or if Beijing is simply trying to frighten protesters into backing down by publicly flaunting its military muscle.

As protesters and Hong Kong authorities become more entrenched in their positions, and hopes for a compromise dim, the reality may be that China is considering both options, said Prof Steve Tsang, the director of the Soas China Institute.

“I don’t think we should see it in a binary way; it’s not either/or. A huge amount of that [rhetoric and footage] is clearly intimidation, but potentially they could also use them,” he said.

“If they truly see what’s happening in Hong Kong as a colour revolution, they will do whatever it takes [to stop it], which is why I feel we are on much more dangerous ground than a few weeks ago.”

The protest movement took off just days after the 30th anniversary of the slaughter around Tiananmen Square and the shadow of the 1989 bloodshed hangs over all discussions of Hong Kong’s fate.

Beijing is as aware of that grim precedent as protesters on the ground, of the international revulsion, and the political and economic isolation that followed.

Any deployment of the People’s Liberation Army would also be hugely damaging to Hong Kong and its economy, and so Beijing is likely to want to keep that only as a last resort.

Quick GuideDemocracy under fire in Hong Kong since 1997

Show

Hong Kong’s democratic struggles since 1997

1 July 1997: Hong Kong, previously a British colony, is returned to China under the framework of “one country, two systems”. The “Basic Law” constitution guarantees to protect, for the next 50 years, the democratic institutions that make Hong Kong distinct from Communist-ruled mainland China.

2003: Hong Kong’s leaders introduce legislation that would forbid acts of treason and subversion against the Chinese government. The bill resembles laws used to charge dissidents on the mainland. An estimated half a million people turn out to protest against the bill. As a result of the backlash, further action on the proposal is halted.

2007: The Basic Law stated that the ultimate aim was for Hong Kong’s voters to achieve a complete democracy, but China decides in 2007 that universal suffrage in elections for the chief executive cannot be implemented until 2017. Some lawmakers are chosen by business and trade groups, while others are elected by vote. In a bid to accelerate a decision on universal suffrage, five lawmakers resign. But this act is followed by the adoption of the Beijing-backed electoral changes, which expand the chief executive’s selection committee and add more seats for lawmakers elected by direct vote. The legislation divides Hong Kong's pro-democracy camp, as some support the reforms while others say they will only delay full democracy while reinforcing a structure that favors Beijing.

2014: The Chinese government introduces a bill allowing Hong Kong residents to vote for their leader in 2017, but with one major caveat: the candidates must be approved by Beijing. Pro-democracy lawmakers are incensed by the bill, which they call an example of “fake universal suffrage” and “fake democracy”. The move triggers a massive protest as crowds occupy some of Hong Kong’s most crowded districts for 70 days. In June 2015, Hong Kong legislators formally reject the bill, and electoral reform stalls. The current chief executive, Carrie Lam, widely seen as the Chinese Communist party’s favoured candidate, is hand-picked in 2017 by a 1,200-person committee dominated by pro-Beijing elites.

2019: Lam pushes amendments to extradition laws that would allow people to be sent to mainland China to face charges. The proposed legislation triggers a huge protest, with organisers putting the turnout at 1 million, and a standoff that forces the legislature to postpone debate on the bills. After weeks of protest, often meeting with violent reprisals from the Hong Kong police, Lam announced that she would withdraw the bill.

“The deployment of PLA troops, however controlled and contained it might seem, will mean the end of Hong Kong and its rapid decline,” said Kenneth Chan, a political science professor at Hong Kong Baptist University.

That would be a big hit for China at a damaging time. The country’s population is ageing, economic growth hit a 30-year low this year, and the national balance sheet is weighed down by huge debt incurred during the boom years.

Instead, Chan said he expected Beijing to explore other ways of crushing protests, through a combination of harsher policing, and political and economic pressure.

They may include “massive arrests by police and escalation of state-sanctioned violence against the activists and protesters; economic sanctions against businesses; censorship and other hidden forms of pressures against universities, civil society groups and the pro-democracy movement”, he said.

The PLA garrison in the city, estimated by Hong Kong’s legislature at between 8,000 and 10,000 troops, would be on standby as both last resort and source of pressure, he added.

Looming over the protests is a deadline of sorts, though. The 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China falls on 1 October. It will be celebrated with a military parade and other activities around the country, and China’s autocratic president, Xi Jinping, is unlikely to want it overshadowed by events in Hong Kong.

Perhaps the biggest question for the future of Hong Kong and its protesters is what he might consider more of a spoiler – crowds still clogging the streets of Hong Kong in a dramatic, democratic denunciation of Xi’s “China dream”, or celebrations held in the bleak wake of a bloody crackdown.