Abstract

A material potentially exhibiting multiple crystalline phases with distinct optoelectronic properties can serve as a phase-change memory material. The sensitivity and kinetics can be enhanced when the two competing phases have large electronic structure contrast and the phase change process is diffusionless and martensitic. In this work, we theoretically and computationally illustrate that such a phase transition could occur in the group-IV monochalcogenide SnSe compound, which can exist in the quantum topologically trivial Pnma-SnSe and nontrivial \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe phases. Furthermore, owing to the electronic band structure differences of these phases, a large contrast in the optical responses in the THz region is revealed. According to the thermodynamic theory for a driven dielectric medium, optomechanical control to trigger a topological phase transition using a linearly polarized laser with selected frequency, power and pulse duration is proposed. We further estimate the critical optical electric field to drive a barrierless transition that can occur on the picosecond timescale. This light actuation strategy does not require fabrication of mechanical contacts or electrical leads and only requires transparency. We predict that an optically driven phase transition accompanied by a large entropy difference can be used in an “optocaloric” cooling device.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phase change memory (PCM) materials are one of the key components of next-generation information storage1. Currently, the most widely used commercialized PCM materials are Ge–Sb–Te alloys2. These materials can exist in both crystalline and amorphous phases with distinct optical or electronic transport features, which are separated by a significant energy barrier. The phase transformation between these phases is reconstructive owing to the diffusional displacements of atoms. The drawback of a temperature-driven transformation is that due to the equipartition theorem, all phonon modes are involved, and thus, the total driving energy and the heat dissipation are significant. Furthermore, the phase change occurs on a timescale on the order of a few to a few hundred nanoseconds. Hence, one would like to find a PCM material that can simultaneously satisfy the following requirements: (i) it can exist in at least two structural phases, (ii) these phases have distinct physical properties that can be easily measured, preferably in a contact-free manner, (iii) the phase transformation is displacive/martensitic, where the atomic motions are diffusionless, and (iv) the directed phase transition preferably occurs within a single phonon oscillation period (picosecond) in the barrier-free limit. The main idea is to strongly bias only the reaction coordinates of the structural transition, instead of exciting all the phonon modes, such as in a temperature-driven transition. With these requirements fulfilled, the phase transition would have the benefits of low energy consumption, low heat load and fast switching speed.

The discovery of topological materials during the past decade has offered ample interesting physical effects3. Transitions between topologically different states have attracted tremendous attention both theoretically and experimentally. One example is group-VI transition metal dichalcogenide (TMD) monolayers, such as MoTe2 and its analogues, which exist in the 2H (normal insulator, NI)4 and 1T′ (topological insulator, TI) phases5. Theoretical predictions have shown that the 2H → 1T′ phase transformation can occur under lithiation6, electron doping7, or tensile strain8. Later experimental efforts showed that such a phase transformation can occur under Ar plasma bombardment9 or gate voltage10. During this process, ~1/6 of the Mo-Te chemical bonds need to be broken, and then, the same number of new Mo-Te bonds will be formed. Hence, even though the energy difference between 2H-MoTe2 and 1T′-MoTe2 is small, the energy barrier separating the two phases is high ( ~ 2000 J/cm3 when we take an energy barrier of 1.05 eV/f.u. and a MoTe2 monolayer thickness of 7.74 Å5,8). Most other topological phase transitions in a single material occur via modulation of their electronic band dispersion under strain engineering11,12, electrostatic gating13,14,15, or temperature change16,17. Some of these phases have a short lifetime (volatile) once the external field is removed. In addition, these phase transitions usually require electrochemical, electrical, or mechanical contacts and patterning. This stimulates us to explore topological phase change materials whose phase transition can be triggered through a noncontacting scheme with intermediate energy barriers18.

In this work, based on thermodynamic analysis and first-principles density functional theory (DFT) calculations, we propose that a group-IV monochalcogenide compound (such as SnSe or other analogues) is a good platform to realize nonvolatile topological phase transition by optomechanical stimulation. This group-IV monochalcogenide compound family possesses a few interesting properties19,20. The SnSe compound can exist in multiple phases, such as in the space groups of Pnma, \(Fm\bar 3m\), and Cmcm. While many studies focus on the high-temperature ( > 800 K) phase transition from Pnma to Cmcm21,22, here, we study the two energetically lower polymorphs, namely, Pnma (ground state) and \(Fm\bar 3m\) (metastable). Geometrically, Pnma-SnSe is a layered structure. This phase has been attracting great interest owing to its good thermoelectric property22,23,24. \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe shows a rocksalt geometry and has been proven theoretically25,26 and experimentally27,28 to be a novel type of quantum topological material – a topological crystalline insulator (TCI) with a large change in near band-edge (NBE) optical susceptibilities. Hence, the topological phase transition between Pnma and \(Fm\bar 3m\) would be interesting and promising for potential applications. Nevertheless, except for foreign atom doping29,30, theoretical studies on such phase transitions are very rare. Here, we apply the random phase approximation (RPA) to calculate the optical response features. Owing to the topological band inversion feature of \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe, its dielectric screening effect is much stronger than that of semiconducting Pnma-SnSe. Therefore, according to the thermodynamic theory of a driven dielectric medium, when the sample is exposed to a linearly polarized laser (LPL) with THz frequency, the free energy of \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe reduces faster with greater alternating electric field strength (the optical tweezers effect) than that of Pmna-SnSe. Hence, we predict a phase transformation between Pnma and \(Fm\bar 3m\) under an intermediate intensity LPL. Such a transformation can even be barrier-free, with significantly enhanced kinetics. Owing to the entropy difference between the two phases, we can even design a thermodynamic phase-change cycle to utilize the “optocaloric” effect of SnSe as a refrigeration medium.

Methods

Density functional theory

We employ DFT calculations31,32 with generalized gradient approximation (GGA)33 treatment of the exchange-correlation energy term using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)34,35. The projector augmented wave (PAW) method36 and a planewave basis set with a cutoff energy of 300 eV are applied to treat the core and valence electrons in the system, respectively. The first Brillouin zone is represented by a Γ-point-centered Monkhorst–Pack k-mesh37 with a grid density of 2π × 0.02 Å−1 along each dimension. The convergence of these parameters is well tested. To correct the underestimation of long-range dispersion in the GGA treatment, we include the semiempirical quantum chemical method DFT-D3 term in the total energy expression38. Other treatments give similar results. The convergence criteria of the total energy and force component are set to 1 × 10−7 eV and 0.001 eV/Å, respectively. Spin-orbit coupling (SOC) is self-consistently included due to the high Z of Sn and Se atoms. We perform ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations and confirm that both phases are thermally stable at room temperature (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Information). To evaluate the finite temperature behavior, we also calculate phonon dispersions and the frequency density of states using the finite displacement method, as implemented in the Phonopy code39.

Results and discussion

When an LPL containing an alternating electric field (\(\vec {\cal{E}}\left( {\omega _0,t} \right) = {\cal{E}}_0e^{ - i\omega _0t}{\hat{\mathbf e}}_i\), where êi is a unit vector along the i-th direction) is applied to the system, its contribution to the free energy can be evaluated via the thermodynamic theory of an external reservoir bath and Legendre transformation. By taking the electric field magnitude as the thermodynamic variable, one adds an additional term into the free energy density (in units of energy/volume)40,

Here, ε(1)(ω0) is the real part of the dielectric function tensor at optical frequency ω0. Note that here, the optical frequency ω0 is much larger than the vibrational frequency ωvib (typically < 6 THz); thus, the ion motion contribution to the dielectric function is neglected. Microscopically, the incident photon carries an optical electric field and excites electron subsystems. Then, phonons are stimulated by electron-phonon coupling. When the phonon displacement is large enough, the system can go beyond elastic deformation and undergo a phase transition.

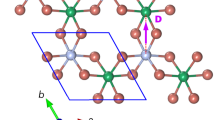

We start our discussions with the geometric and energetic features of the SnSe compound in both the \(Fm\bar 3m\) and Pnma phases (Fig. 1). Pnma-SnSe shows a layered structure. According to previous works, each SnSe layer possesses an in-plane (along the y-direction) ferroelectricity (P0 = 1.5 × 10−10 C/m)41,42. In the bulk Pnma-SnSe compound, the layers are antiferroelectrically stacked, exhibiting a centrosymmetric structure with no net spontaneous polarization. This structure has been demonstrated to be a semiconductor with an optical band gap of 0.9 eV, showing high-performance thermoelectric behavior (ZT > 2.2)22,23. In contrast, in the rocksalt \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe, all the Sn and Se atoms are ionically bonded. Its band dispersion calculation reveals an inverted band order near the Fermi level, which is topologically protected by spatial mirror symmetry25. Thus, this structure belongs to the TCI family, with a calculated band gap of ~ 0.2 eV43. Our DFT-D3 scheme yields Pnma-SnSe lattice parameters of a = 4.169 Å, b = 4.515 Å, and c = 11.558 Å (each supercell contains two SnSe layers) and \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe lattice parameters of a = b = c = 4.247 Å. These results agree well with experimental data (Pnma-SnSe: a = 4.15 Å, b = 4.45 Å, and c = 11.50 Å; \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe: a = b = c = 4.24 Å)44,45. From the atomic structures, one observes that when the even and odd numbered layers in Pnma-SnSe alternatively translate along the ± y-direction by 0.18 × b (green arrows in Fig. 1a), this phase can change into \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe. During this internal coordinate shuffling, the supercell transformation strain is actually small (compared with, e.g., ref. 46); thus, little mesoscopic elastic constraint strain energy is required when a certain embedded region undergoes transformation. The volume difference between the two phases is within 0.5%. These facts demonstrate that the phase transition is martensitic and displacive, without requiring random atomic diffusion. Hence, the time scale of the phase transition can be greatly reduced, and the energy input to drive the phase transition is also small.

Atomically geometric phase transition of SnSe. Geometric structures of the SnSe compound in the a layered Pnma and b rocksalt \(Fm\bar 3m\) phases. In a, empty arrows represent the spontaneous electric polarization of each layer, and green arrows show the translation direction of each layer to form the \(Fm\bar 3m\) phase. The blue dashed rectangle represents the simulation supercell.

Our DFT calculations show that Pnma-SnSe has a lower ground state energy than \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe by 17 meV per formula unit (meV/f.u.). This agrees well with previous DFT works43. To estimate the energy barrier between the two phases and phase transition kinetics, we apply the cell-variable nudged elastic band (NEB) method47,48 to calculate the reaction path versus total energy. As shown in Fig. 2a, the energy barrier from Pnma-SnSe to \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe is calculated to be 42 meV/f.u., corresponding to 123 J/cm3. This value is much smaller than the energy barrier from monolayer 2H-MoTe2 to 1T′-MoTe2 (~2000 J/cm3). The phonon spectrum of the saddle point crystal structure is shown in Fig. 2b, where only one large imaginary optical branch can be observed (at Γ). This imaginary mode corresponds to reaction coordinate shuffling to the Pnma phase, while the imaginary modes at Z (0, 0, 1/2) correspond to the transition to \(Fm\bar 3m\). When the system transits back from \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe to Pnma-SnSe, the energy barrier will be 25 meV/f.u. (73 J/cm3). By applying the Arrhenius law to estimate the transition rate, \(k = \upsilon _0{\mathrm{exp}}\left(- {\frac{{NE_{\mathrm{b}}}}{{k_{\mathrm{B}}T}}} \right)\) (where Eb is the energy barrier, N is the total number of formula units, and ν0 = 10−12 s is the trial frequency), we note that \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe can exist for over 20 years at room temperature (T = 300 K) when N = 60 (~3 nm3). On the other hand, the moderate energy barrier value per unit also indicate that the phase change between the two phases may be triggered by intermediate external field energy input with fast kinetics.

Thermodynamic and topological change in SnSe compound. a DFT-calculated total energy and band gap versus reaction path during NEB simulation. The inset shows the geometric structure of the saddle point. The gray shaded area indicates the topological phase transition point (energy band gap closes) between the NI (Pnma-SnSe) and TCI (\(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe) states. b Phonon spectrum of the saddle point, where only one optical soft mode appears around the Γ-point. The inset shows the atomic vibration of the imaginary normal mode at the Brillouin zone center, where the atoms in the two compositional layers have opposite in-plane motions.

One fascinating feature during this structural phase transformation is the accompanying topological electronic phase transition. As previously discussed, Pnma-SnSe is a topologically trivial semiconductor, with its highest valence band and lowest conduction band located far from the Fermi level [Fig. 3a, left panel]. In contrast, the topologically nontrivial band gap insulator \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe has a valence and conduction band inversion at the L-point in the Brillouin zone [Fig. 3b, left panel]. We plot the calculated band dispersions in the Supplementary Information, Fig. S2. Such a band topology change leads to quite a few important contrasting properties between the two phases, such as robust metallic surface states without backscattering. During a topological phase transition, a band gap closing and reopening process usually occurs. Thus, we also calculated the band gap value variation along the reaction path [Fig. 2a]. The band gap closing structure lies in the \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe energy basin. Here, we show that the optical responses to an LPL of the two phases are very different. One can examine the electron-contributed dielectric function based on the random phase approximation (RPA)49,50 via

Here, \(| {u_{n,{\mathbf{k}}}}{\rangle}\) and En,k are the periodic part of the Bloch wavefunction and its corresponding eigenvalue of band n at k, with indices v and c representing valence and conduction bands, respectively. ξ is a phenomenological damping parameter representing the temperature and disorder effects of the sample. From the above equation, one sees that the real part of the dielectric function is determined by two factors: (i) the direct energy band gap (Ec,k – Ev,k) and (ii) the Berry connection \({\vec{\mathrm A}}_{nm}\left( {\mathbf{k}} \right) = i{\langle{u_{n,{\mathbf{k}}}}}{\mathrm{|}}\nabla _{\mathbf{k}}{\mathrm{|}}u_{m,{\mathbf{k}}}{\rangle}\). Hence, compared with the NI Pnma-SnSe, the TCI \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe has not only a relatively small band gap but also a larger Berry connection magnitude owing to its inverted band order with an enhanced band correlation. These facts indicate that the magnitude of ε(1) of \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe should be much larger than that of Pnma-SnSe, giving a large contrast of their NBE optical responses.

We thus calculate the dielectric functions of the two phases by choosing ξ = 0.025 eV, as shown in the right panels of Fig. 3a (Pnma-SnSe) and Fig. 3b (\(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe). Due to the geometric anisotropy, the x-, y-, and z-components of ε(ω) of Pnma-SnSe are slightly different. In our current setup, when the incident photon energy is less than the direct band gap (ℏω < 0.70 eV, where ε(2)(ω) is zero), the real parts of the dielectric functions of Pnma-SnSe almost remain constant, with εxx(1)(ω) = 19.9, εyy(1)(ω) = 17.5, and εzz(1)(ω) = 17.9. On the other hand, the real parts of the dielectric functions of isotropic \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe below the direct band gap are much larger. For example, at an incident energy ℏω0 = 0.17 eV, the calculated values are εxx(1)(ω0) = εyy(1)(ω0) = εzz(1)(ω0) = 109.9, which are nearly six times those of Pnma-SnSe at the same incident photon energy. We also plot the optical response of the DFT-calculated saddle point in the Supplementary Information (Fig. S3). We use a simplified k·p model to illustrate the topological contribution to the optical responses of \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe (see the Supplementary Information for details). We find a relationship between the band gap at L-point (1/2, 1/2, 1/2) (measured as 2|m| in the model) and the dielectric constant, \(\varepsilon ^{\left( 1 \right)}\left( 0 \right) = 1 + \alpha \left| m \right|^{ - \gamma }\). For the topologically nontrivial band structure, the fitting coefficient α is much larger than that of the trivial band structure, indicating a large Berry connection contribution, as previously discussed.

Owing to the centrosymmetric geometric feature of both phases, one can hardly apply a static electric field to drive the phase transition, as in ferroelectrics. Alternatively, here, we propose a noncontacting optomechanical approach. According to our previous discussions, the free energies GE (Eq. 1) under LPL pulse (ℏω0 = 0.17 eV) exposure of the two phases are different. Taking a y-directional LPL as an example (the other directions are similar), we calculate the free energy difference between the two phases under different electric field magnitudes (Fig. 4),

Here, Ω is the volume of a formula unit, and ε0 is the vacuum permittivity. As the electric field magnitude ε0 increases, the Gibbs free energy difference ΔG quadratically reduces to zero. We see that the critical electric field is 0.35 V/nm. Above this value, LPL exposure makes \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe more stable, enabling a martensitic topological phase transition. To drive the opposite phase transition (from \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe to Pnma-SnSe), even though the Pnma phase has a lower energy, we can apply a laser frequency at ℏω0′ = 0.25 eV to accelerate the process. At this incident energy, the calculated εxx(1)(ω0′) values are 20.1, 41.2, and 6.5 for Pnma-SnSe, the transition saddle point, and \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe, respectively. We estimate the electric field required to drive an ultrafast barrier-free phase transformation. For the Pnma to \(Fm\bar 3m\) transition, the incident LPL pulse can be ℏω0′′ = 0.12 eV along the y-direction, and the calculated dielectric functions are εyy(1)(ω0′′) = 17.2, 107.5 and 78.7 for Pnma, the saddle point and \(Fm\bar 3m\), respectively. Hence, the electric field strength of 0.56 V/nm would drive a barrier-free phase transformation. For the \(Fm\bar 3m\) to Pnma transition, an electric field along the x-direction of 0.69 V/nm (incident energy ℏω0′ = 0.25 eV) can suppress the energy barrier. When the bulk energy barrier (in units of meV/f.u.) vanishes, the transition kinetics is similar to that of spinodal decomposition, but in terms of the phonon displacement48 instead of the chemical composition order parameter. With such a driving force that causes a vanishing bulk energy barrier, the typical nucleation-growth kinetics can be avoided, and the transition process could occur within picoseconds. We also illustrate this process (see the Supplementary Information for details), which reveals that the barrier-free phase transition occurs with a discontinuity of the electric displacement. Note that the phase transition is not temperature driven. Therefore, it does not require a large amount of latent heat to trigger the phase transition, as in the conventional temperature-driven process.

Since standard DFT calculations underestimate the band gap, here, we also use a more accurate approach to verify our calculations. As shown in Fig. S4 (Supplementary Information), we plot the real parts of the dielectric functions of both phases, calculated by the hybrid functional HSE0651,52, which has been proven to correct the band gap underestimation of the GGA approach. We find that the overall trends are the same. If the incident photon energy is chosen to be ℏω0 = 0.34 eV, then the calculated values for Pnma-SnSe are εxx(1)(ω0) = 14.0, εyy(1)(ω0) = 12.4, and εzz(1)(ω0) = 12.8 and for \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe are εxx(1)(ω0) = εyy(1)(ω0) = εzz(1)(ω0) = 70.7. Quasi-particle calculations with exciton binding correction (GW-BSE)53,54,55,56 are also performed (Fig. S5). The dielectric function difference between the two phases is much larger. At an incident energy of ℏω0 = 0.14 eV, the calculated results are εxx(1)(ω0) = εyy(1)(ω0) = εzz(1)(ω0) = 185.0 (\(Fm\bar 3m\)) and εxx(1)(ω0) = 10.2, εyy(1)(ω0) = 8.5, and εzz(1)(ω0) = 11.7 (Pnma). The corresponding electric field strength to trigger the phase transition from Pnma to \(Fm\bar 3m\) is 0.25 V/nm (laser power of 8.3 × 109 W/cm2). The dielectric function value of the TCI \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe is larger than that of Pnma-SnSe, indicating the robustness of the optomechanically driven martensitic phase transition. To accelerate the transition from \(Fm\bar 3m\) to Pnma, an incident light of ℏω0′ = 0.5 eV (along x) can be applied, with its calculated εxx(1)(ω0′) being 12.3 and 1.8 for Pnma and \(Fm\bar 3m\), respectively.

We then propose that this optomechanically driven phase transformation of SnSe will lead to a promising cooling mechanism57, which we refer to as the optocaloric effect. We calculate the entropy (S = Sph + Sel, where Sph and Sel are the phononic and electronic entropies, respectively) difference between the two phases (Fig. 5a). The calculation details can be found in the Supplementary Information. The largest entropy change appears at T = 40 K, with ΔS = –0.23 kB/f.u. At room temperature (T = 300 K), \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe has a higher entropy than Pnma-SnSe by 0.01 kB/f.u. (kB is the Boltzmann constant, corresponding to 0.5 J K−1 kg−1). Such latent heat (TΔS) between two phases (one stable, one metastable, at T when optical field is turned off) can be used to drive cooling, similar to producing ice from liquid water in a summer day using a specially made mechanical shocking device, and then letting ice → liquid water for cooling purposes on that summer day. This is not a Carnot cycle (Fig. 5b), which is based on a single-phase medium (ideal gas) and consisting of four quasi-static thermodynamic legs (two isothermal which contributes sensible heat, and two adiabatic legs, and all four legs require gradual pressure/volume changes). Here, instead, we propose to use latent heat rather than sensible heat during a two-legged cycle (Fig. 5c): in one leg of the loop we use optomechanical shock to non-quasistatically drive the phase transition from the stable → metastable phase (stable and metastable phases defined when the optical field is turned off, for that T), and in the other leg we allow the metastable phase to relax back to the stable phase thermally. This will be a two-step loop. During the first step, the \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe phase absorbs latent heat (Qin) and quasi-statically (and isothermally) transforms to Pnma-SnSe, like ice melting in a cold drink. In the second step, we apply a laser pulse to drive Pnma-SnSe back to the \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnSe phase. This leg is not a quasi-static process (out of local thermal equilibrium, since the reaction coordinate gains a lot more kinetic energy than the other vibrational degrees of freedom), which cannot be represented by a thermodynamic state curve in an equilibrium thermodynamic macro-state plot like Fig. 5b.

a Entropy difference between two phases as a function of temperature. b Entropy-temperature (S-T) in a Carnot thermodynamic cycle. c Phase-change cooling cycle, that is significantly different from the Carnot cycle. Here solid lines denote quasi-static processes, whereas dashed line denotes out-of-thermal-equilibrium process.

We also perform calculations for other analogous group-IV monochalcogenide compounds (Fig. S7). During geometric optimization, Pnma-PbSe and Pnma-PbTe relax to the \(Fm\bar 3m\) structure owing to the large size of the Pb ion. \(Fm\bar 3m\)-PbS is also energetically more stable than Pnma-PbS. Hence, alloyed materials, such as Pb1−xSnxX (X = S, Se, Te)58 compounds, are possible candidates for tuning Pnma ↔ \(Fm\bar 3m\) transitions. For example, when x = 0.30, experimental evidence shows that the topological transition temperature is ~ 250 K in Pb1−xSnxSe59. We also know that in the \(Fm\bar 3m\)-GeTe and \(Fm\bar 3m\)-SnTe compounds, there is a spontaneous cubic-to-rhombohedral structural phase transition in which the sublattice Ge/Sn and Te atoms displace along the [111] direction60,61. This forms a ferroelectric state, which is topologically trivial with a wide band gap. Under hydrostatic pressure, the rocksalt \(Fm\bar 3m\) phase can be dynamically stable. Hence, unless under pressure, the phase transition between the two phases is not accompanied by topological changes in the electronic band structure, but nonetheless has certain dielectric response contrast. The GeSe, GeS, SnS, and PbS compounds all have similar results to SnSe, whose Pnma and \(Fm\bar 3m\) phases are locally stable when not optically pumped. The optical responses of these compounds are also similar to those of SnSe (Fig. S8).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we systematically calculate the energetics and optical responses of the SnSe compound and chemical analogues in their low temperature phases, namely, normal insulator Pnma and topological crystalline insulator \(Fm\bar 3m\). We propose that the phase transition can also be driven when one applies a pulsed laser with a selected frequency. Such a topological phase transition, similar to the transformation of TMD monolayers from 2H to 1T′ but with lower energy barrier and energy input, belongs to martensitic displacive phase transitions, but with very little transformation strain during and after the transformation, and thus has low elastic constraint penalty energy, ensuring fast kinetics and reversibility. We predict a promising optocaloric effect in SnSe based on the phase-change cycle, taking advantage of the low dissipation and stress of such rapid optically driven transitions, which could be useful as a refrigerant.

References

Zhang, W., Mazzarello, R., Wuttig, M. & Ma, E. Designing crystallization in phase-change materials for universal memory and neuro-inspired computing. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 150 (2019).

Wuttig, M. & Yamada, N. Phase-change materials for rewriteable data storage. Nat. Mater. 6, 824–832 (2007).

Wen, X.-G. Colloquium: zoo of quantum-topological phases of matter. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 041004 (2017).

Wang, Q. H., Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Kis, A., Coleman, J. N. & Strano, M. S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 699–712 (2012).

Qian, X.-F., Liu, J.-W., Fu, L. & Li, J. Quantum spin hall effect in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Science 346, 1344–1347 (2014).

Kan, M. et al. Structures and phase transition of a MoS2 monolayer. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 1515–1522 (2014).

Li, Y., Duerloo, K.-A. N., Wauson, K. & Reed, E. J. Structural semiconductor-to-semimetal phase transition in two-dimensional materials induced by electrostatic gating. Nat. Commun. 7, 10671 (2016).

Li, W. & Li, J. Ferroelasticity and domain physics in two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers. Nat. Commun. 7, 10843 (2016).

Zhu, J. et al. Argon plasma induced phase transition in monolayer MoS2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 10216–10219 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Structural phase transition in monolayer MoTe2 driven by electrostatic doping. Nature 550, 487–491 (2017).

Qi, Y. et al. Topological quantum phase transition and superconductivity induced by pressure in the bismuth tellurohalide BiTeI. Adv. Mater. 29, 1605965 (2017).

Zhou, J. & Jena, P. Two-dimensional topological crystalline quantum spin hall effect in transition metal intercalated compounds. Phys. Rev. B 95, 081102(R) (2017).

Collins, J. L. et al. Electric-field-tuned topological phase transition in ultrathin Na3Bi. Nature 564, 390–394 (2018).

Liu, Q., Zhang, X., Abdalla, L. B., Fazzio, A. & Zunger, A. Switching a normal insulator into a topological insulator via electric field with application to phosphorene. Nano Lett. 15, 1222–1228 (2015).

Kim, J. et al. Observation of tunable band gap and anisotropic dirac semimetal state in black phosphorus. Science 349, 723–726 (2015).

Xu, B. et al. Temperature-driven topological phase transition and intermediate dirac semimetal phase in ZrTe5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 187401 (2018).

Monserrat, B. & Vanderbilt, D. Temperature effects in the band structure of topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 226801 (2016).

Zhou, J., Xu, H., Li, Y., Jaramillo, R. & Li, J. Opto-mechanics driven fast martensitic transition in two-dimensional materials. Nano Lett. 18, 7794–7800 (2018).

Guo, Y., Zhou, S., Bai, Y. & Zhao, J. Oxidation resistance of monolayer group-IV monochalcogenides. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 12013–12020 (2017).

Cheng, K. et al. Lateral heterostructures of monolayer group-IV monochalcogenides: band alignment and electronic properties. J. Mater. Chem. C. 5, 3788–3795 (2017).

Dewandre, A. et al. Two-step phase transition in SnSe and the origins of its high power factor from first principles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 276601 (2016).

Zhao, L.-D. et al. Ultralow thermal conductivity and high thermoelectric figure of merit in SnSe crystals. Nature 508, 373–377 (2014).

Chen, Z.-G., Shi, X., Zhao, L.-D. & Zou, J. High-performance SnSe thermoelectric materials: progress and future challenge. Prog. Mater. Sci. 97, 283–346 (2018).

Feng, D. et al. Enhanced thermoelectric properties of SnSe polycrystals via texture control. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 31821 (2016).

Liu, J. et al. Spin-filtered edge states with an electrically tunable gap in a two-dimensional topological crystalline insulator. Nat. Mater. 13, 178–183 (2014).

Hsieh, T. H. et al. Topological crystalline insulators in the SnTe material class. Nat. Commun. 3, 982 (2012).

Wang, Z. et al. Molecular beam epitaxy-grown SnSe in the rock-salt structure: an artificial topological crystalline insulator material. Adv. Mater. 27, 4150–4154 (2015).

Zeljkovic, I. et al. Strain engineering dirac surface states in heteroepitaxial topological crystalline insulator thin films. Nat. Nanotech. 10, 849–853 (2015).

Inoue, T., Hiramatsu, H., Hosono, H. & Kamiya, T. Nonequilibrium rock-salt-type Pb-doped SnSe with high carrier mobilities ≈ 300 cm2/(Vs). Chem. Mater. 28, 2278–2286 (2016).

Shen, J., Woods, J. M., Xie, Y., Morales-Acosta, M. D. & Cha, J. J. Structural phase transition and carrier density tuning in SnSexTe1‐x nanoplates. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2, 1600144 (2016).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864–B871 (1964).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133–A1138 (1965).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, S. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Togo, A., Oba, F. & Tanaka, I. First-principles calculations of the ferroelastic transition between rutile-type and CaCl2-Type SiO2 at high pressures. Phys. Rev. B 78, 134106 (2008).

Landau, L. D. & Lifshitz, E. M. Electrodynamics of Continuous Media, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2 edition, 1984.

Fei, R., Kang, W. & Yang, L. Ferroelectricity and Phase Transitions in Monolayer Group-IV Monochalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 097601 (2016).

Wu, M. & Zeng, X. C. Intrinsic Ferroelasticity and/or Multiferroicity in Two-Dimensional Phosphorene and Phosphorene Analogues. Nano Lett. 16, 3236–3241 (2016).

Sun, Y. et al. Rocksalt SnS and SnSe: native topological crystalline insulators. Phys. Rev. B 88, 235122 (2013).

Wiedemeier, H. & von Schnering, H. G. Refinement of the structures of GeS, GeSe, SnS and SnSe. Z. Kristallogr. 148, 295–303 (1978).

Mariano, A. N. & Chopra, K. L. Polymorphism in some IV-VI compounds induced by high pressure and thin-film epitaxial growth. Appl. Phys. Lett. 10, 282 (1967).

Ishii, A., Li, J. & Ogata, S. Shuffling-controlled versus strain-controlled deformation twinning: the case for HCP Mg twin nucleation. Inter. J. Plast. 82, 32 (2016).

Henkelman, G. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Henkelman, G. & Jónsson, H. Improved tangent estimate in the nudged elastic band method for finding minimum energy paths and saddle points. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9978–9985 (2000).

Gajdoš, M., Hummer, K., Kresse, G., Furthmüller, J. & Bechstedt, F. Linear optical properties in the projector-augmented wave methodology. Phys. Rev. B 73, 045112 (2006).

Liu, X.-H., Gu, J.-F., Shen, Y. & Li, J. Crystal metamorphosis at stress extremes: how soft phonons turn into lattice defects. NPG Asia Mater. 8, e320 (2016).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207–8215 (2003).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Erratum: “Hybrid Functionals Based on A Screened Coulomb Potential” [J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207 (2003)]. J. Chem. Phys. 124, 219906 (2006).

Hedin, L. New method for calculating the one-particle green's function with application to the electron-gas problem. Phys. Rev. 139, A796–A823 (1965).

Hybertsen, M. S. & Louie, S. G. First-principles theory of quasiparticles: calculation of band gaps in semiconductors and insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 1418–1421 (1985).

Salpeter, E. E. & Bethe, H. A. A relativistic equation for bound-state problems. Phys. Rev. 84, 1232–1242 (1951).

Onida, G., Reining, L. & Rubio, A. Electronic excitations: density-functional versus many-body Green’s-function approaches. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 601–659 (2002).

Li, B. et al. Colossal barocaloric effects in plastic crystals. Nature 567, 506–510 (2019).

Kalish, S. et al. Contrasting the surface phonon dispersion of Pb0.7Sn0.3Se in its topologically trivial and nontrivial phases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 116101 (2019).

Neupane, M. et al. Topological phase diagram and saddle point singularity in a tunable topological crystalline insulator. Phys. Rev. B 92, 075131 (2015).

Sugai, S., Murase, K. & Kawamura, H. Observation of soft TO-phonon in SnTe by Raman scattering. Solid State Commun. 23, 127–129 (1977).

Chang, K. et al. Discovery of robust in-plane ferroelectricity in atomic-thick SnTe. Science 353, 274–278 (2016).

Acknowledgements

J.Z. acknowledges the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants Nos. 21903063 and 11974270, and the Young Talent Startup Program of Xi’an Jiaotong University. S.Z. acknowledges the NSFC grant under No. 11904350. J.Z. thanks Xiaoyin Li for helpful discussions on phonon simulations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, J., Zhang, S. & Li, J. Normal-to-topological insulator martensitic phase transition in group-IV monochalcogenides driven by light. NPG Asia Mater 12, 2 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-019-0188-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-019-0188-9

This article is cited by

-

Electrically switchable anisotropic polariton propagation in a ferroelectric van der Waals semiconductor

Nature Nanotechnology (2023)

-

Increasing the number of topological nodal lines in semimetals via uniaxial pressure

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Colossal switchable photocurrents in topological Janus transition metal dichalcogenides

npj Computational Materials (2021)