On a normal operating day, Pittsburgh International Airport (PIT) sees an average of 13,000 to 15,000 passengers coming through its gates. But there's no such thing as a "normal" day at PIT anymore—or any other airport in the U.S., for that matter. Because of the ongoing devastation of the COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic, PIT is lucky to see even 1,200 travelers in a day.

Of course, PIT pales in size to Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport (ATL), the busiest flight hub in the country. With ATL's monthly passenger traffic plummeting from 7.8 million in February 2020 to just 453,000 fliers in April—not to mention 22 confirmed COVID-19 cases for TSA employees on site as of June 14—the airport has temporarily shuttered the majority of its storefronts, prompting its general manager to say it may take anywhere from two to five years for passenger volume at ATL to return to pre-COVID-19 levels.

"We think that there’s up-until-vaccine and then there’s post-vaccine," PIT spokesman Bob Kerlik tells Popular Mechanics. "We think up-until-vaccine, we will see some leveling off of traffic that’s above this 95 percent drop. We’re already seeing a small uptick beginning. But until there’s a vaccine, we aren’t going to see the type of steady growth that we were seeing through early March."

From relatively tiny regional airports like PIT to behemoths like ATL, practically every airport on the planet has felt the carnage of the coronavirus, instantly turning into ghost towns when the world's travelers decided they weren't comfortable flying anymore. But these hubs can't just close up shop and wait for a vaccine to appear; they must take the measures now to stop the spread of SARS-COV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19), use technology to keep travelers safe, and prevent the further erosion of an already-struggling industry.

So how do you reimagine and execute a radical overhaul of your business—the kind that would normally take years to pull off—in a matter of months?

You call in the machines. At PIT, the country's first autonomous robot janitors aren't just scrubbing the floors, but also using specialized ultraviolet lamps to instantly neutralize the virus. At ATL, meanwhile, restaurants and shops have pivoted to touchless payment, the airport has made over 4 million face masks available to passengers for free, and technicians have installed 250 "smart" hand-sanitizing stations, which self-monitor to alert staff when refills are necessary, a spokesperson tells Popular Mechanics.

And there are more plans in the works, including fogging disinfectants, which spray cleaning chemicals in mists; antimicrobial alloy coatings for high-touch spaces, like water fountains; and germicidal UV-light fixtures in restrooms.

The airport of the future is already upon us, ready to soothe us back into our routines. And while some hopeful patterns are emerging, from immunization passports to disinfecting tunnels, the question still stands: Will any of this be enough?

Touchless Check-In

Gone are the days of waiting in long lines to check in to your flight with your state ID or passport. Self-check-in kiosks actually stretch back to 1995, when the now-defunct Continental Airlines first installed them at New Jersey's Newark Liberty International (EWR).

But these touchscreens have one major sticking point: you have to, you know, touch them. So at some airports, biometrics like iris scanners and facial recognition cameras are replacing the need for passports or ID cards. This isn't an entirely new concept, given that ATL, in partnership with Delta Air Lines, became the first U.S. airport to introduce a biometric terminal back in 2018.

As a release at the time notes, virtually all of the 25,000 customers who travel through the airport's Concourse F each week chose the optional biometric process, with less than 2 percent opting out. It even ended up saving 9 minutes at boarding time.

Since then, Delta has added biometric check-in service to airports in Detroit, Minneapolis, and Salt Lake City. The technology is by no means pervasive, but the pandemic is accelerating the pace of adoption.

Dubai International Airport (DXB), meanwhile, uses a "smart tunnel" system. It collects biometric data for immigration control and speeds up the process to take only 15 seconds, so you don't have to wait in line to show your passport to a security worker at a booth.

Robot Janitors

Since May, Hong Kong International Airport (HKG) has been using what it calls "Intelligent Sterilization Robots" to sterilize public toilets and terminals. According to a release, it can kill up to 99.99 percent of bacteria in its vicinity, both in the air and on surfaces, in 10 minutes.

Around the same time, Pittsburgh became the first U.S. city to use disinfecting robots at its airport. At PIT, officials have teamed up with Carnegie Robotics, a local startup, to bring autonomous floor scrubbers to terminals. The partnership had already been in place for about a year before the COVID-19 outbreak, but the team quickly pivoted to include disinfectant properties in addition to floor-scrubbing capabilities.

In a matter of weeks, PIT outfitted the autonomous floor scrubbers with UV-C lights, Katherine Karolick, the airport's senior vice president of information technology, tells Popular Mechanics.

"UV-C has been used in hospitals for decades as a way to kill microorganisms, and it seemed like something that would definitely make sense in the airport," she says.

But these aren't off-the-shelf ultraviolet lights. Engineers at Carnegie Robotics had to specifically build the fixtures. The stronger the lights—and the closer they're positioned to the surface in question—the faster they work. At the moment, four of these are in use at the airport, but Karolick says they're evaluating how many will be optimal in the future.

"UV light, whether from the sun or a lightbulb, destroys the [genetic material] of the virus ... so it makes it ineffective," Karolick says. UV-C wavelengths are between 200 and 300 nanometers, which means they're germicidal. The light can inactivate bacteria, viruses, and protozoa without chemicals, making it environmentally friendly, too.

Researchers are also currently swabbing the floors after the robot makes its rounds at PIT, says Karolick. Then, they take the samples back to the lab to analyze them. At the moment, the airport is also in talks with a local "major health provider" to assist in the testing.

Since the rollout, other airports have reached out to learn more about the robot janitors. Karolick says airports are "highly collaborative," as they want the passenger experience to be as consistent as possible with respect to health and cleanliness standards during the pandemic. You wouldn't want to have a great experience while departing from one airport, only to land and feel extremely uncomfortable at the next one.

Health Passports

Chile, Germany, Italy, the U.K., and the U.S. have all tossed around the idea of an "immunity passport," which is a physical or digital document that certifies a person has already been infected with SARS-CoV-2, meaning they have immunity to COVID-19. Under this framework, these people would be exempt from social distancing restrictions, could return to work and daily life, and travel more easily.

However, as research in the peer-reviewed Lancet journal points out, there isn't any definitive proof—yet—that people who have recovered from COVID-19 and have antibodies are safe from a second infection. So immunity passports can't truly be validated until the medical research catches up.

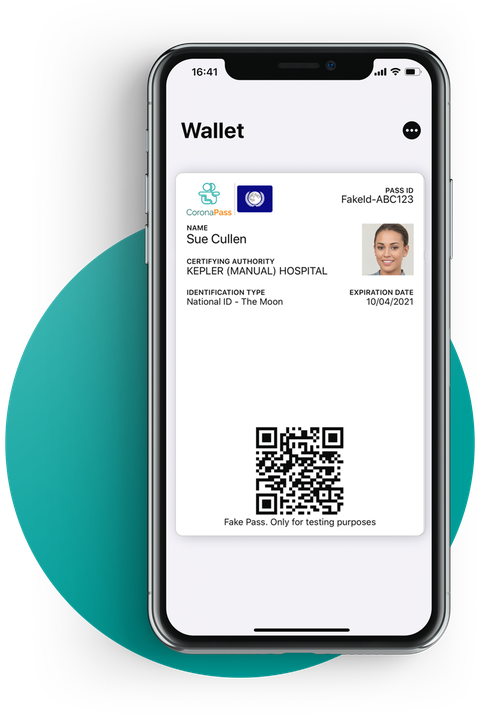

But that hasn't stopped one company from trying. Bizagi, a U.K.-based automation software producer, launched a new app called CoronaPass back in April. The app is meant to "demonstrate immunity to authorities when required, based on the results of rapidly expanding COVID-19 anti-body testing," according to a release.

In theory, the premise makes sense. Until a vaccine is widely available—and that likely won't be until the end of this year or the beginning of 2021 at the earliest—an immunity passport could help the economy, and those who have built up immunity, return to pre-COVID-19 activity levels.

If the results of a person's serological test (which detects antibodies) demonstrate they do have antibodies, they can receive a CoronaPass QR code that they can then print or present via mobile phone to authorities. The idea is very similar to a mobile boarding pass.

But even Bigazi CEO Gustavo Gomez admits the jury is still out, saying the "science of immunity is still being explored" in the release.

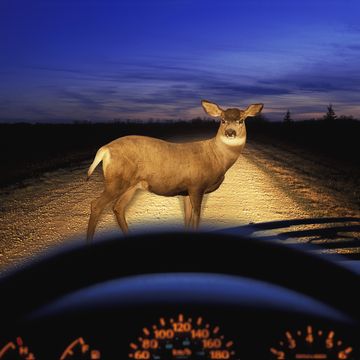

Thermal Cameras

At Dulles International Airport (IAD) in Washington, D.C., and Tampa International Airport (TPA) in Florida, airport authorities are introducing new thermal cameras. Created by the Texas-based Infrared Cameras Inc., the cameras detect elevated skin temperatures, which may be correlated to the possible presence of fever. Only further testing can rule out whether that's due to COVID-19, another ailment, or another issue altogether, but the company says it's a contact-free—and accurate—way to screen travelers.

Elsewhere in the U.S., airport authorities are considering implementing self-serve kiosks that not only help passengers check in, but also take their temperature. One manufacturer of these devices, Pyramid Computer, announced a prototype that can supposedly combine contactless temperature screening with software from ZipKey, the tech provider for border-control passport verification and biometrics services.

The machines, which use over 1,000 measuring points, can record body temperature in less than one second, the company says, meaning airports could process up to 700 travelers per hour.

At Hamad International Airport (DOH) in Doha, Qatar, temperature screening takes the form of a "Smart Screening Helmet." In a release, the airport says the helmets employ both thermal and temperature screening.

There's some precedent for these concepts. Infrared Cameras, Inc. says some airports used its line of thermal cameras during the 2014 Ebola outbreak and even the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARs) outbreak in 2003.

Disinfectant Tunnels

Some airports are using disinfectant tunnels to keep luggage free of viruses across facilities, from arrival to departure. This is mostly happening abroad, which isn't surprising, given that airports in the Middle East are among the most advanced in the world.

At Delhi's Indira Gandhi International Airport (DEL), for example, ultraviolet tunnels at Terminal 3 help disinfect luggage in baggage areas. Disinfecting will occur twice: once when the passenger hands over their bag, and once again when they pick it up upon arrival. DOH in Qatar uses similar technology.

Some companies have even built disinfectant tunnels meant for humans. Stretch Structures, which has offices in the U.S., U.K., New Zealand, and Australia, has unveiled what it's calling a "decontamination and sanitation tunnel." Using atomized biocides and virucide sprays, the company says the tunnel could help maintain a virus-free environment at not only entrances to airports, but also pharmacies and other civilian businesses.

The tunnel uses an arc-shaped array of nozzles that spray the environment with chemicals to kill bacteria and viruses. A traffic light configuration tied to a motion sensor ushers passengers through the tunnel.

Whether people will appreciate walking through a cloud of chemical mist is a whole separate issue, but when air travel picks back up with the advent of a vaccine, technology companies and airport authorities will have a better idea of which interventions make the most sense. And it's quite likely that even after the threat of COVID-19 subsides, these new technologies will be here to stay.

Correction, posted June 29, 2020: This story has been updated to reflect the correct spelling of Bizagi, the company that created CoronaPass.