Deep-sea volcanoes: Windows into the subsurface

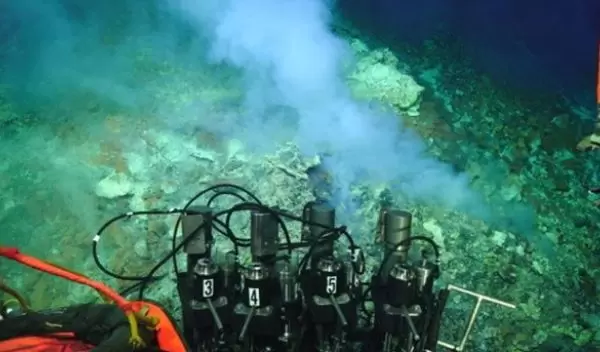

Although hydrothermally active submarine volcanoes account for much of Earth's volcanism and are mineral-rich biological hotspots, very little is known about microbial diversity in these systems.

In the journal PNAS, U.S. National Science Foundation-funded researchers show that at one such volcano, Brothers submarine arc volcano northeast of New Zealand, the geological history and subsurface hydrothermal fluid paths testify to the complexity of microbial life on the seafloor. The researchers also provide insights into how past and present subsurface processes could be imprinted in that microbial diversity.

"Microbes in hot springs everywhere get their energy in part from the geochemistry of the hot water," says Anna-Louise Reysenbach, a microbiologist at Portland State University. "It's the same for the Brothers volcano seafloor hot springs. Since both seawater- and magmatic gas-influenced hydrothermal systems coexist at Brothers, we predicted that the microbes in the active magmatic cone sites would be very different from those on the caldera wall."

What the scientists did not expect was that there would also be two very different microbial communities in close proximity on the caldera wall. A caldera is a large cauldron-like hollow that forms shortly after the emptying of a magma chamber in a volcanic eruption.

Recent International Ocean Discovery Program drilling and geophysical measurements provide evidence that, after the collapse of the original volcano to form the present-day caldera, the earliest magmatic-hydrothermal system became overprinted by a more seawater-dominated system.

The researchers show that one of the caldera communities aligns with microbes from the magmatically influenced hydrothermal vents of the more recent cone that has grown up from the caldera floor. It's likely that a combination of different subsurface mineral assemblages intersected by the circulating hydrothermal fluids helps shape distinct microbial communities on the caldera wall, the scientists say.