On March 17, otherwise known as my 38th birthday, a press release landed in my inbox: The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), the professional body overseeing fertility care in the U.S., was recommending the suspension of all “non-urgent” treatments, including in vitro fertilization and egg freezing, due to COVID-19.

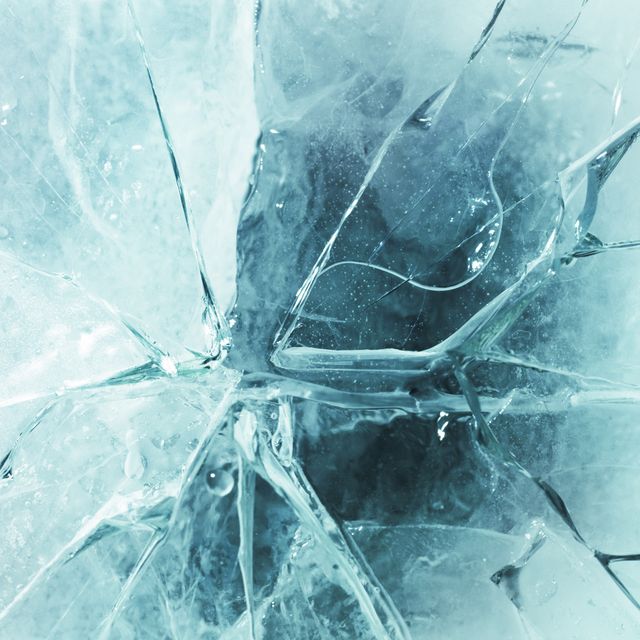

As many people shut themselves inside, I pictured empty clinics, unmanned cryostorage tanks, and thousands of frozen eggs and embryos left to the vagaries of equipment that has been known to fail. I thought of my own eggs—13 in a storage tank in Italy, another 7 in Spain—and wondered if anyone was keeping tabs. It felt tacky, selfish, even rude, to wonder about whether anyone was minding a handful of oocytes as the virus killed thousands. And yet those eggs, retrieved at great effort and cost, are my best chances at creating a child one day. Frozen when I was 34 and 36 years old, they are biological time capsules, remnants of an irretrievable time before my womb turned cobwebby.

There are few areas of medicine that are not, in some way, time sensitive. Catching a cancer early, for example, can mean the difference between surviving or not. Reproduction, and women’s fertility in particular, is fraught with its own sense of urgency. The advent of egg freezing—and the marketing around it—has pushed many to consider family-making long before they might be ready. “The best age to freeze your eggs is however old you are today, because I can’t make you younger,” one doctor at an egg-freezing information session I attended earlier this year told the crowd. She was met with grim, forced chuckles.

At least five years passed between when I learned about egg freezing, in my late twenties, and when I finally did it. I could pin the delay on a handful of promising, but ultimately doomed, relationships as well as a job and a move—but they were all incidental. The real factor that stopped me was money.

Egg freezing in the U.S. costs an average of roughly $18,000 per cycle, according to FertilityIQ, a website that collects pricing and patient review data for fertility centers, including medications. At 33, I was torn between using my savings for a nest egg or frozen eggs, but ended up opting to buy an apartment in Washington, DC, where I was living at the time. I made the decision knowing it would take at least two years to save again for the procedure—time I felt I didn’t have.

My friend Suzy had frozen her eggs in Bologna, Italy, and told me the cost was less than half what it was in the U.S. So I took freelance copyediting jobs, working nights and weekends, to save up enough to freeze my eggs one year after I bought the apartment. In October 2016, I put my new apartment on Airbnb and flew to Italy on a Turkish Airlines flight purchased with credit card miles.

Two years later, after a period of intense job-related travel—a time when I went on more work trips than dates—I decided to freeze my eggs again, as experts recommend having at least 20 for a decent chance at a baby. This time I went to Madrid, where I stayed with dear friends—a mother, father, and seven-year-old daughter. They had always treated me like family, and I felt both loved and cared for and, at times, utterly alone. Especially at night, when I would stay up after everyone else was asleep, jabbing myself with an array of needles, feeling deeply, profoundly, and eternally single.

Since March, when the quarantine began in earnest, two of my closest friends have given birth, a former colleague sent around her sonogram, and I learned of several pregnancies in my social circle. If I hadn’t felt the urgency to make babies back in February, I definitely did by April. But a not-so-little problem remained: I am nearly 4,000 miles away from the eggs that I’ll likely need to call up for duty. As I mulled the prospect of children, the abysmal American response to the virus made it a moot point. This summer, when the European Union banned most U.S. citizens from entering as COVID spiraled out of control in a majority of the 50 states, booking a ticket to Spain or Italy ceased to be an option.

What do delays brought on by the coronavirus mean for women who are trying to freeze their eggs or get pregnant? In spite of the messages we get from the fertility industry about needing to act fast, in the midst of the virus, here was a group of doctors advising potentially tens of thousands of women across the country to hold on for a second while they figured this whole COVID thing out.

Within days of the ASRM announcement, a Change.org petition calling for women’s rights to fertility treatment began racking up signatures. Patients shared stories online of canceled IVF cycles and expensive medications expiring in the fridge. Many acknowledged the unknowns of the coronavirus likely meant their clinic was doing the right thing, but the anxiety was palpable. “I’m 46.” “I’ll be too old.” “There go my hopes.”

Beverly Reed, MD, the Texas-based reproductive endocrinologist who started the petition, noted that the ASRM recommendation came at a time when much of the country was not yet on lockdown. She spent that March day on the phone, canceling appointments, and came home to see spring breakers on TV living it up in Florida. “To contrast that with the sadness that my patients were feeling was heartbreaking,” Reed says. She pushes against the idea that suspending fertility treatments isn’t a matter of life and death: “Isn’t this about creating life?” she asks.

The research on aging and fertility is clear: The older a patient is, the more poorly her ovaries function, meaning she produces fewer and less-viable eggs. However, studies have shown that a delay of up to three months, even for patients in their late thirties and early forties, has little effect on IVF outcomes. If the studies are correct, then hopefully the moratorium will not severely affect women who were undergoing or gearing up for procedures this past spring. By the end of April, the ASRM released protocols for clinics considering reopening. But for people like me, who took advantage of our mobility to seek affordable fertility care abroad, the ongoing travel ban means I may have traded accessibly priced treatment for actual access to my eggs.

It is clear the coronavirus has changed the notion of “essential.” Most obviously, we have redefined which workers and businesses are deemed essential. Confined to our homes, piled on top of loved ones or stranded away from them, we are asking ourselves: What is important? What can we let go of, and what can we not afford to ignore?

I did, I am embarrassed to say, inquire after my eggs back in mid-March. The patient coordinator at the Spanish clinic wrote back two days later: “Don’t worry about your eggs. Everything is okay.” She said the clinic was closed and the staff was in quarantine, but “everything is under control.” I never heard back from the Italian clinic, but in late April I received a bill for the annual storage fee (about $350) and felt reassured.

While I have been fortunate enough to keep working during the crisis, money and time remain elusive. How much money do I need to save for the drugs that will hopefully turn my frozen eggs into healthy babies one day, and how much time do I need to save it? Will Americans be allowed back into Spain and Italy next year? And perhaps most importantly, what—ultimately—might this delay cost me in the end?

This article appears in the November 2020 issue of ELLE.