Journalism, it’s often said, is the first-draft of history. That draft sometimes is found under a big headline on the front page. Other times it’s less conspicuous, perhaps on Page 6. Almanacs are full of lists of global and national historic events. But our “This Day in History” feature invites you to not just peruse a list, but to take a trip back in time to see how a significant event originally was reported in the Chicago Tribune.

Check back each day for what’s new … and old.

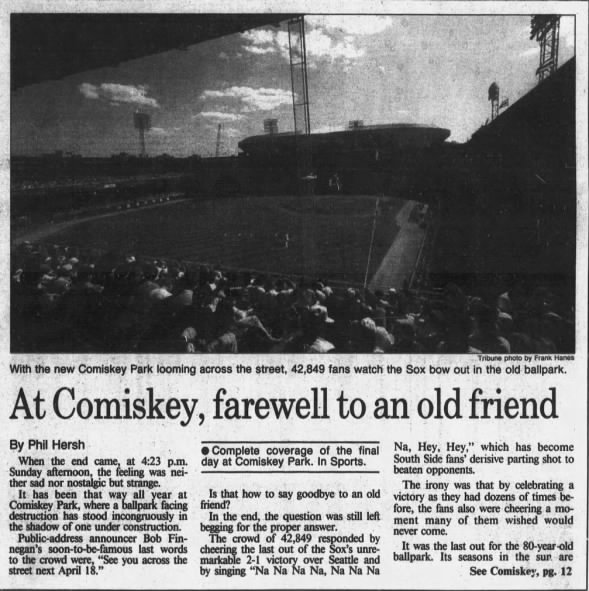

White Sox play last game at old Comiskey Park — Sept. 30, 1990

“At Comiskey, farewell to an old friend”

An announced crowd of 42,849 sang “Na Na Hey Hey Kiss Him Goodbye” as the Chicago White Sox and their fans bid adieu to old Comiskey Park on Sept. 30, 1990.

Today, there’s a parking lot where so many memories and so much MLB and Negro League history occurred. For visitors to the new stadium that replaced it, the site of the old home plate and baselines remain marked off.

“When the end came, at 4:23 p.m. Sunday afternoon, the feeling was neither sad nor nostalgic but strange,” the Tribune’s Phil Hersh wrote for the front-page.

At the time of its retirement, the 80-year-old edifice, long billed as “the baseball palace of the world,” already was dwarfed by the new Comiskey Park – now known as Guaranteed Rate Field – under construction across the street at 35th and Shields.

Razing the old Comiskey would continue into 1991 and the Sox’s debut season in the new stadium, leaving an open wound for long-time fans mourning the past.

No one would ever refer to old Comiskey as “a lyric little bandbox,” as John Updike famously once wrote of Boston’s Fenway Park, two years its junior, but it was a beloved landmark nevertheless, even in its indisputable decline.

But the new ballpark, built with public monies won by threatening to move the White Sox to Florida, had the revenue-generating suites and other features commonplace around major-league baseball.

“What’s that they say about it getting darkest just before the dawn?” Sox Chairman Jerry Reinsdorf said. “When you think how close we came to leaving. The thing is, if you somehow waved a magic wand and made this stadium structurally sound, it still wouldn’t be financially sound. We couldn’t have competed. Now we can compete.”

It would take years and critical renovations that made it less sterile before many fans could fully embrace the new ballpark, the last built in MLB before retro stadiums designed to evoke parks of yore became fashionable.

As for competing, the White Sox headed into the 2020 postseason, having only reached the American League Championship Series twice since moving to the new ballpark.

But one of those years, 2005, produced both a pennant and World Series – something that hadn’t happened in the old joint since 1959 and 1917, respectively – and that, along with the passage of time, has enabled all but the most stubbornly resistant old fans to bond with the new stadium.

With a 2-1 victory over the Seattle Mariners in the old Comiskey’s finale, they finished up compiling a 3,024-2,926 record there, a .508 winning percentage.

The Tribune’s Andrew Bagnato noted Sox shortstop Ozzie Guillen “couldn’t stand the place for most of his career,” but was emotional at the very end.

“My tears are coming, but it’s great to see that in a ballpark,” Guillen said after the last game. “We won this for the fans. They deserve a winner in Chicago.”

When the Sox finally did win, the manager of that ’05 AL champion and World Series title team would, of course, be Guillen.

—

The first draft of Chicago history at your fingertips at newspapers.com.

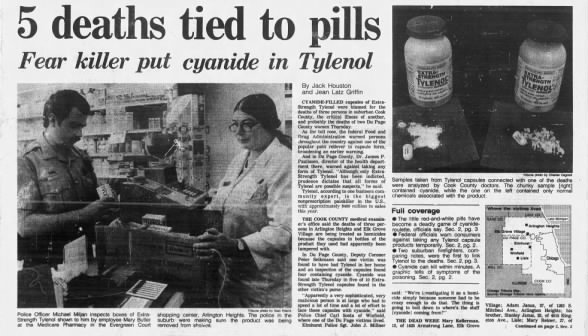

The first of the Tylenol murders — Sept. 29, 1982

“5 deaths tied to pills”

The 12-year-old girl in Elk Grove Village had a cold. A man in Arlington Heights, 27, felt minor chest pains. Each took Extra Strength Tylenol and died on Sept. 19, 1982, the first of seven fatalities from cyanide-filled capsules.

The late 27-year-old’s brother, 25, gathered with family to mourn their sudden loss, and broke out the same tampered jar of pills for a headache.

Unaware this is what had killed his sibling, he was soon dead as well. The brother’s wife, 19, also took Extra Strength Tylenol, and eventually died from it, too.

Three other Chicago-area women would die from cyanide-laced capsules in the coming days.

“Apparently a very sophisticated, very malicious person is at large who had to spend a lot of time and a lot of effort to lace these capsules with cyanide,” Winfield Police Chief Carl Sosta said as the death toll hit five.

No one has ever been tried or convicted for the homicides.

A New York man named James William Lewis, who sent Johnson & Johnson a letter taking credit for the murders and demanding $1 million to stop tampering with pills, was sent to prison for extortion. But authorities never were able to tie him directly to the cyanide-filled capsules.

Other suspects have been investigated, but to no avail.

Copycat crimes claimed more lives, helping convince the industry to embrace tamper-resistant packaging that’s in use today. Such tampering is now a federal crime.

Johnson & Johnson won plaudits for its handling of the crisis, moving quickly to gets its product off store shelves and then making moves to regain lost market share.

The first of the deaths were baffling to health officials. The young girl seemed to have suffered a stroke. A contagion was feared when the siblings felled.

It was two suburban firefighters comparing notes on the sudden deaths of those earliest deaths – Richard Keyworth of Elk Grove Village and Philip Cappitelli of Arlington Heights – who put together the possible connection with Tylenol.

Their supposition was relayed to Dr. James Kim of Northwest Community Hospital, who confirmed critical details with police.

It’s a nightmarish crime that haunts many still.

Ted Williams becomes last MLB player to hit better than .400 — Sept. 28, 1941

“Williams ends season with .405 average”

With six hits in eight at-bats in a season-ending Red Sox road double-header vs. the Athletics, Ted Williams finished with a .4057 batting average on Sept. 28, 1941.

The Tribune rounded that figure down to .405 in its headline. Baseball rounded up to .406, a number burnished by the fact no one in 80 subsequent major-league seasons has surpassed .400.

The closest anyone has come is Tony Gwynn, who hit .394 in a strike-abbreviated 1994 season in which he appeared in 110 of his team’s 117 games and had 475 plate appearances and 419 at-bats.

For players who have played a full schedule, George Brett is tops with .390 with 419 at-bats in 1980. Williams hit .388 in 1957 as Rod Carew did in (1977), followed by Larry Walker .379 (1999) and Stan Musial .376 (1948).

Williams, who was 23 and wrapping up just his third major-league season with the Red Sox, entered the final day of the 1941 season at .39955 and could have sat out the double-header to ensure a .400 finish.

Instead, he went four for five, including his 37th home run of the season in Boston’s 12-11 Game 1 victory. Then he went two for three in the 7-1 nightcap loss.

If the achievement seemed underplayed by the Tribune, it’s worth remembering that while it was the first time anyone in the majors had surpassed .400 in 10 years (and since 1923 in the American League), five players had accounted for eight .400 seasons from 1920 to ’30.

That includes 1922, when George Sisler’s .420 for the Browns beat out Ty Cobb’s .401 for the Tigers in the American League, and the Giants’ Rogers Hornsby led the National League at .401. (Sisler twice hit better than .400 in his career. Cobb and Hornsby each managed it three times.)

Williams’ feat also came in the same 1941 season of Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak for the eventual World Series champion Yankees en route to being named AL most valuable player.

Pete Rose, with a 44 game run in 1978, is the only player since to string together more than 39 in a row.

Relatively few recall that Williams began a 23-game hitting streak of his own on the same day that DiMaggio’s streak started. And while DiMaggio hit .408 during his 56-game run, Williams batted .412 over the same span.

For the season, Williams had 185 hits, 147 walks and only struck out 27 times with 456 official at-bats and 606 plate appearances.

He played in 143 games and was hitless in only 22. He never went more than seven at-bats.

For the sake of his average, it undoubtedly helped Williams that he had to sit out two stretches during the season.

He rebounded from missing most of April with a broken bone in one of his feet, batting .436 in May, including a two-week stretch where he hit .536. He also was out 12 days with an ankle injury after the All-Star break, going 12 for 22 in his return.

Yet if sacrifice flies were – like today – not counted as at-bats, researchers say his average would have been higher.

Williams would go on to win five more batting titles before retiring after the 1960 season, despite missing three seasons serving in World War II and most of two others because of Korean War service.

The Warren Commission report is issued — Sept. 27, 1964

“The assassination story”

Ten months after President John F. Kennedy’s death, the special government panel chaired by Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren to investigate the assassination in Dallas made public its findings on Sept. 27, 1964.

The President’s Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, better known as the Warren Commission, concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald killed Kennedy and was acting alone.

Oswald’s independence was asserted “despite his record as a defector to the Soviet Union, his stay there from October, 1959, to June, 1962, and his visits to the Cuban and Russian embassies in Mexico City just before the shooting,” the Tribune reported.

The report also said Jack Ruby was acting alone when he killed Oswald two days later.

Warren’s panel recommended improvements to presidential security it said might’ve thwarted Oswald, including better threat detection and coordination among federal and local authorities.

“Other than this disclosure that the fourth Presidential assassination in American history might have been prevented, the 888-page report contained no new or startling revelations,” the Tribune’s Willard Edwards wrote.

“Much of the bulky document, to be supplemented later with the release of 18 to 20 volumes of testimony, was devoted to an exhaustive examination and rejection of rumors, and theories – many of them fantastic – which have gained world-wide circulation.

“These stories have gained credence abroad, where the public has been led by published articles and books to believe that Kennedy died as a result of either a communist or a so-called ‘rightist’ plot in which several persons must have been involved.”

Besides Warren, the panel included Sens. John Sherman Cooper and Richard Russell Jr., Reps. Hale Boggs and (future President) Gerald Ford, former CIA Director Allen Dulles and former World Bank President John J. McCoy. Among the assistant counsel was future Sen. Arlen Specter.

If part of their goal was to snuff out speculation some kind of conspiracy or organized crime plot was behind the Kennedy assassination, they failed miserably.

Kennedy conspiracy theories remain a thriving cottage industry to this day, and mistrust by some of its findings has fueled a belief in other conspiracies.

The groundbreaking stand-up comedian Mort Sahl took to reading excerpts of the Warren Report on stage, riffing on what he saw as inaccuracies, contradictions and other shortcomings, and mocking conclusions.

Oliver Stone’s 1991 film “JFK” fed off and on doubts about the idea of a one gunman theory.

There have been numerous successive investigations, though none has been able to convince doubters in a meaningful way.

A Gallup Poll conducted days after the assassination found only 29% of Americans believed Oswald acted alone and 52% believed some group or element was also responsible.

While the numbers have been higher at various times over the year, a 2017 poll conducted for FiveThirtyEight.com found 33% believed one man killed JFK and 61% believed others were involved.

First Kennedy-Nixon debate — Sept. 26, 1960

“Candidates tell aims!”

The modern presidential campaign debate – in reality a joint news conference – was born September 26, 1960, as Vice President Richard Nixon joined Sen. John F. Kennedy in the one-time horse stable on Chicago’s McClurg Court that was home to Chicago’s CBS-2.

“Only the innate dramatic character of the encounter saved it from being a rather dry recital of the comparative merits of the Republican and Democratic programs,” the Tribune’s Willard Edwards wrote. “There were no flashes of wit, no memorable phrases, no give-and-take with a political flavor.

“It was a political television show familiar to many viewers – the usual questions about medical care for the aged, balanced budgets, farm surpluses, and teachers’ salaries.”

Even if the first of four historic Kennedy-Nixon debates was a bit of a snooze, that didn’t stop the Tribune from being all over it, even publishing a transcript.

The Chicago joint-appearance was the most-watched of the four, drawing an estimated 66.4 million viewers plus a radio audience.

CBS’ Howard K. Smith was moderator with NBC’s Sander Vanocur, CBS’ Stuart Novins ABC’s Bob Fleming and Charles Warren of Mutual Broadcasting as panelists. The subject matter was limited to domestic policy.

Don Hewitt, who would go on to create “60 Minutes” eight years later, was executive producer.

There was no instant analysis offered after the debate, as is customary today. Sans pundits weighing in and anyone offering spin, the audience was left to make of it what they wished.

There is no denying Nixon’s makeup was poorly applied. He sweated. His grey suit blended into the background. And he was thin from having lost weight during a recent hospitalization from a knee injury.

Kennedy, only four years younger, looked more youthful, dressed better for TV, and came across as more confident.

But despite the mythology that’s grown over the intervening 60 years, it’s hard to say the debates were the key factor carrying Kennedy to victory. They might have helped put Kennedy on equal footing with Nixon for some uncertain of his experience.

Kennedy picking Sen. Lyndon Johnson of Texas as his running mate likely was more critical as Johnson helped the Democrats win not just the Lone Star State but other Southern states in what proved to be a very tight race.

James Baughman, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, wrote in a 2010 article that “most of those polled believed Kennedy ‘won’ the first debate and Nixon the third, with no clear winner in the other two.”

Baughman also noted that by the time of the debates most voters had made up their minds, and undecided voters were “in all probability less interested in the election, and less likely to be watching.”

That said, Nixon, who had rejected President Eisenhower advice to not share a stage with Kennedy, would be among those who came to scapegoat the debates for losing the campaign. He had no interest in debating Hubert Humphrey in 1968 and George McGovern in ’72.

The concept was only resurrected because President Gerald Ford thought it might help in 1976, when polls showed him trailing Gov. Jimmy Carter.

Debates have been part of presidential campaigns ever since.

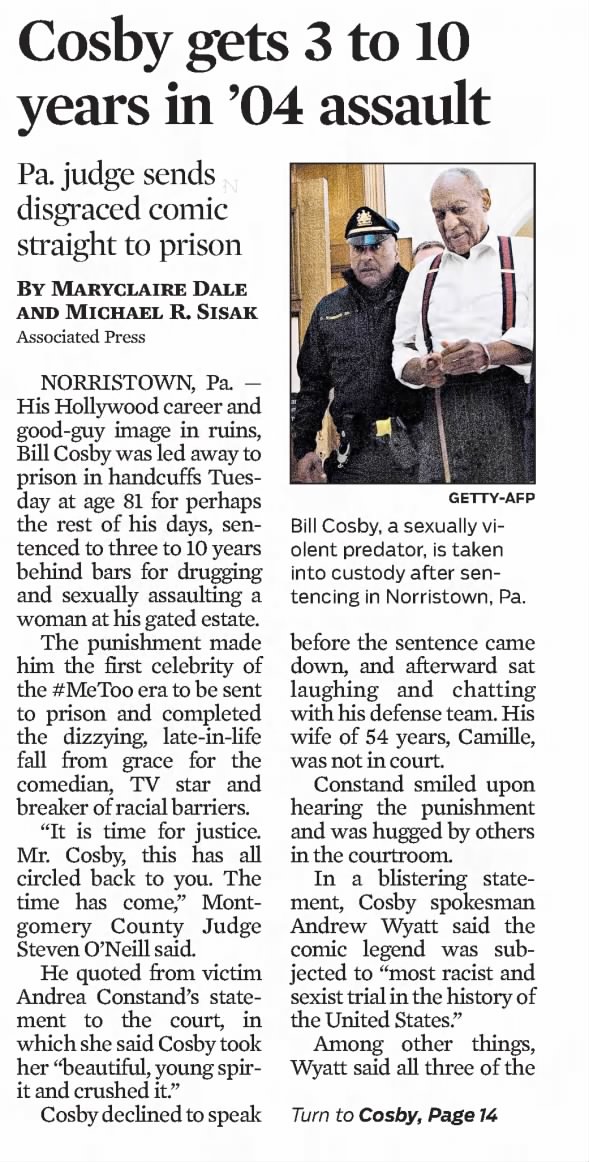

Bill Cosby goes to prison — Sept. 25, 2018

“Cosby gets 3 to 10 years in ’04 assault”

Bill Cosby, once a beloved comedian, author and actor with a well-polished image as America’s Dad, was sent to prison in handcuffs on Sept. 25, 2018.

“It is time for justice, Mr. Cosby. This has all circled back to you. The time has come, Montgomery County, Pa., Judge Steven O’Neill said, sentencing the fallen star, 81, to three to 10 years behind bars plus a $25,000 fine for drugging then sexually assaulting a woman at his suburban Philadelphia home.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court in June granted Cosby an appeal, agreeing to review part of his case. An April request for an early release from prison as a precaution against exposure to COVID-19 was denied.

“The punishment made him the first celebrity the first celebrity of the #MeToo era to be sent to prison and completed the late-in-life fall from grace for the comedian, TV star and breaker of racial barriers,” the Tribune’s front-page story of Cosby’s sentencing said.

Sixty or so women came forward with similar experiences over a span of decades, largely ignored previously.

But the conviction was for a 2004 attack on violating Andrea Constand, a women’s basketball administrator at Temple University, Cosby’s alma mater.

Cosby claimed the encounter was consensual and Cosby’s lawyers cast Constand as a “con artist” who framed him, having already scored a $3.4 million civil settlement from the star more than a decade earlier.

His lawyers also unsuccessfully argued that Cosby was too frail and weak to serve a prison sentence and asked for house arrest.

While Cosby himself said nothing after his sentencing, a spokesman said the star of “The Cosby Show,” “Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids” and “I Spy” was subjected to the “most racist and sexist trial in the history of the United States.”

In sending him to State Correctional Institution Phoenix at Collegeville, Pa., O’Neill called Cosby a “sexually violent predator”

An earlier trial on Constand’s accusations ended in a hung jury in 2017.

Constand originally had gone to authorities a year after she regained consciousness at Cosby’s home with her clothes askew. The district attorney did not take up the case.

The public at large had no idea of Cosby’s behavior – and accusers such as Constand were unable to get much traction – until stand-up comedian Hannibal Burress riffed about Cosby being a rapist.

A different prosecutor reopened Constand’s case. Other women came forward. And a federal judge unsealed damning testimony from Constand’s civil suit in which, the Associated Press said, “Cosby described sexual encounters with a string of actresses, models and other young women, and talked about obtaining Quaaludes to give to those he wanted to sleep with.”

CBS’ ’60 Minutes’ debuts — Sept. 24, 1968

“A lot can happen in an hour. When it’s 60 Minutes.”

A news institution was born on Sept. 24, 1968, with the launch of CBS’ “60 Minutes.”

“The hour, presided over by ‘editors’ Harry Reasoner and Mike Wallace, was an interesting collection of feature stories,” the Tribune’s Clay Gowran wrote in his next-day review.

Gowran wrote those stories ranged “from lively, informal and exclusive footage of Richard Nixon and Hubert Humphrey in their hotel suites at the moment of their nominations, to an interview about police with Ramsey Clark, (the) United States attorney general who has been criticized as soft on criminals and hard on cops.”

While Gowran said the newsmagazine program “looks like a worthwhile addition to serious – but still entertaining – television,” the review appeared along critiques of other programs that debuted that same night.

And between it, “The Doris Day Show,” “Lancer,” “The Mod Squad” and “That’s Life,” it was the last one – a daring ABC musical-comedy following the life and love of a couple played by Robert Morse and E.J. Peaker – that Gowran branded the “best of the offerings, and probably the most vulnerable.”

Gowran was right about vulnerability. “That’s Life” lasted one season, “Lancer” made it two, and “The Doris Day Show” and “The Mod Squad” each made it five.

Meanwhile, executive producer Don Hewitt’s “60 Minutes,” originally launched as a bi-weekly series, is still alive and ticking. Season 53 began earlier this month.

Besides Nixon, Humphrey and Clark, the opening hour was a mixed bag.

Included were a trio of European journalists discussing the U.S. electoral system, a commentary from columnist Art Buchwald, snippets of scripted conversation between two characters in silhouette (one was future “60” commentator Andy Rooney) and a bit of Saul Bass’ Oscar-winning short “Why Man Creates.”

Only the Clark story truly resembled something “60 Minutes” might showcase today.

Wallace and Reasoner closed with a commentary, reflecting on the Bass film and reality vs. perception.

“If this broadcast does what we hope it will do,” Wallace said, “it will report reality.”

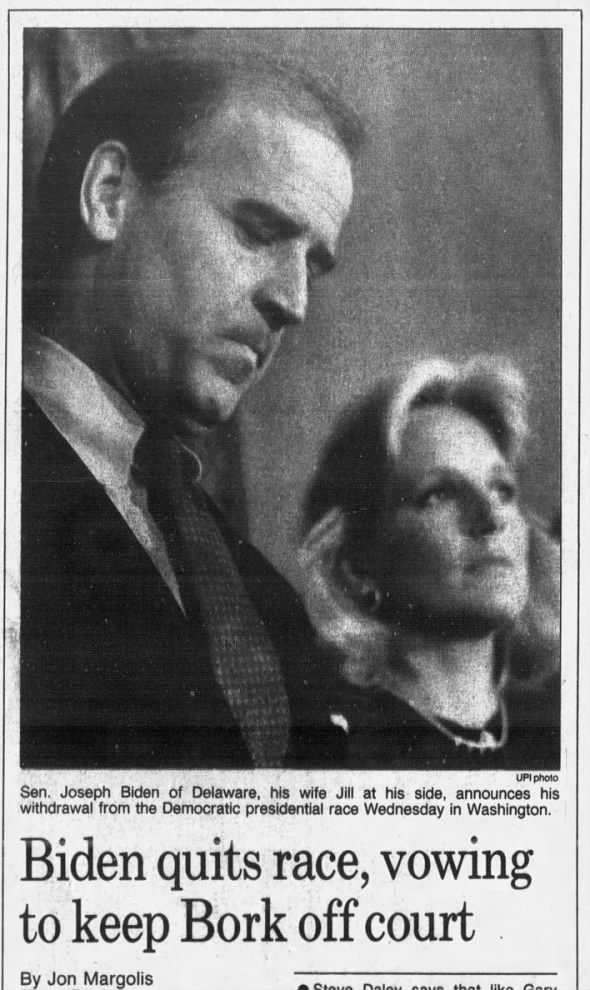

Biden gives up ’88 White House run — Sept. 23, 1987

“Biden quits race, vowing to keep Bork off court”

“There’ll be other presidential campaigns, and I’ll be there,” Sen. Joseph Biden said on Sept. 27, 1987, announcing the end of his 1988 run for the White House. “There’ll be other opportunities, there’ll be other battles in other places, and I’ll be there.”

Biden would be elected Vice President as Barack Obama’s running mate in 2008 and today is the Democratic presidential nominee.

But in ’87, the Delaware Democrat, then 44, had his ambitions foiled by a series of self-inflicted wounds.

That left him rededicated to thwarting the Supreme Court nomination of Robert Bork by the Senate Judiciary Committee, which Biden chaired. (Bork had been a key figure in the scandalous “Saturday Night Massacre” at the Department of Justice under President Nixon.)

“It’s time for me to do just what I would have done had I not won in Iowa and just what I would have done had I lost on the convention floor,” Biden said. “It’s time for me to assess my mistakes and make sure that I don’t make them again.”

Those mistakes included incorporating unattributed passages from the late Robert F. Kennedy and British Labor Party leader Neil Kinnock in speeches, as well as overstating his prowess in law school at Syracuse University.

There also was a plagiarism incident in 1965 as a first-year law student that Biden said was the unintentional result of not understanding how to write a legal paper. He subsequently was allowed to retake the course and passed.

Biden’s exit from the Democratic field came four months after a decision by former Sen. Gary Hart to drop out – temporarily, it turned out – following a Miami Herald report on his relationship with Donna Rice.

“Joe Biden’s public leave-taking was not only far more gracious than Hart’s, but it came with a savvy analysis of the current campaign atmosphere never before articulated by a failed presidential hopeful,” the Tribune’s Steve Daley offered as analysis.

“Smiling a joyless, brittle smile, Biden told reporters that he understood ‘that when the tide begins to roll,’ it requires ‘all the time, energy and concentration’ of a candidate to get a campaign ‘back on track.’ What that means is that the scope of news coverage magnifies and accelerates events; once the blood is in the water, to continue Biden’s metaphor, there is no turning back.”

Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis ultimately emerged as the nominee the next year, losing to Vice President George H.W. Bush in the election to succeed President Ronald Reagan.

“I’m angry with myself for having been put in the position – put myself in the position – of having to make this choice,” Biden said. “And I am no less frustrated at the environment of presidential politics that makes it so difficult to let the American people measure the whole Joe Biden and not just misstatements that I have made.”

Alluding to how Biden’s first wife and baby daughter were killed right after his election to the Senate in 1972, an associate of Biden’s told the Tribune’s Jon Margolis: “This is not the worst thing that ever happened to Joe.”

Irving Berlin dies — Sept. 22, 1989

“Songwriter Irving Berlin Dies at 101”

Irving Berlin, the Russian-born writer of songs such as “God Bless America” that fed and fed off his rags-to-riches American success story, died on Sept. 22, 1989, in New York.

He was 101.

Asked if Berlin had been ill, son-in-law Alton E. Peters was quoted in the Tribune’s front-page report as saying: “No, he was 101 years old. … He just fell asleep.”

“An actor, singer and songwriter, Mr. Berlin began his career in the early days of vaudeville and his songs for a time so dominated the stage and screen that the late composer, Jerome Kern, said: ‘Berlin has no place in America music. He is American music,'” the story said.

George Gershwin called him “the greatest songwriter that has ever lived.”

Born Israel Baline, Berlin came to the United States at age 5 with his family, settling on New York’s Lower East Side. He grew up poor but knew of no other life. He dropped out of school at 13, and an early job was as a singing waiter.

Over his career he would write more than 1,000 songs. His first big hit was “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” in 1911. His “Puttin’ on the Ritz” made the charts 72 years later, thanks to a version by the Dutch artist Taco.

He wrote the enduring holiday standards “White Christmas” and “Easter Parade.” His “I Like Ike” helped elect Dwight Eisenhower president.

To read a list of his songs is to find yourself humming at some point, so familiar are so many of them.

Among those ingrained in the national consciousness are: “Always,” “Anything You Can Do (I Can Do Better),” “Blue Skies,” “Cheek to Cheek,” “Heat Wave,” “I Got the Sun in the Mornin’ (and the Moon at Night),” “How Dry I Am,” “Oh! How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning,” “A Pretty Girl is Like a Melody,” “Rock-A-Bye Baby,” “There’s No Business Like Show Business” and “What’ll I Do?”

Along the way, Berlin picked up plenty of honors, including an Oscar, a Tony, a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award and Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Violinist Isaac Stern, at a Carnegie Hall celebration of Berlin’s 100th birthday, said that until Berlin began writing songs, “American popular music had no voice of its own. We were a hodge-podge of nationalities and noises. But he heard nothing but melodies. American music was born at his piano.”

Ironically, Berlin could not read sheet music.

He was self-taught, playing by ear, and plunking out piano tunes with one finger. Even as an established songwriter, he used a special device to effect key changes.

But he wrote from the heart with lyrics that reflected how real people spoke, lived and loved.

“Out of the fabric of our lives, Irving Berlin has given us a place we call home,” Stern said. “It was this love (of the United States) that gave him the strength to write the music that now lasts forever.”

ABC’s ‘Monday Night Football’ debuts — Sept. 21, 1970

“Sound off, Sports fans!”

It was a seminal moment for media and sports when ABC’s “Monday Night Football” with Howard Cosell, Keith Jackson and Don Meredith in the booth made its series debut from Cleveland on Sept. 21, 1970.

America, clearly, was ready for some football.

The Tribune’s staff gave the Browns’ 31-21 prime-time victory over the New York Jets 50 years ago and the launch of a phenomenally popular franchise no special notice even as it amassed a sizable audience.

But the Tribune’s readers did, and that engagement with the audience may help explain why “MNF” is an enduring cultural touchstone to this day.

Complaints about Cosell – loud, nasal, abrasive, opinionated, very much a New Yorker and a counterpoint to the adulating views of sports figures common in the business at the time – became a common topic in the newspaper’s “Sound off, Sports fans!” feature.

Sandwiched between notes about the Bears’ Jack Concannon and the Cubs’ Joe Pepitone four days after the game, the first critiques began to appear in print.

“I was one of the millions to watch the Cleveland Brown-New York Jet game on the night of Sept. 21,” one reader wrote. “It was a great football game except for the announcing job performed by Howard Cosell.”

Another reader was impressed with the analysis of “Dandy” Don Meredith and the candor of ABC’s announcers.

“One thing about this Monday night production,” the reader continued, “ABC’s men are not afraid to tell a viewer who the guilty player was on infractions of the rules. This is something that the other networks have been squeamish about. They should all tell it as it is.”

That, of course, was a Cosell hallmark.

Week 2 inspired one reader to “start a campaign to get Howard Cosell out of football broadcasting. He is mainly a man of superlatives and cliches, constantly repeating the obvious. I didn’t think anyone could ruin a good football game, but he sure comes close. Cosell really proves that ‘silence is golden.'”

A few days later, another said of Cosell: “His tasteless comments insult the intelligence of sports fans.”

These were not isolated criticisms. The 1988 book “Monday Night Mayhem” by Bill Carter and Marc Gunther, quotes sponsor Henry Ford II telling ABC to dump you-know-who, saying the “gab between him and Meredith made it difficult to “concentrate on the football.”

Executive producer Roone Arledge resisted, and a star was born.

Then again, Cosell, a former lawyer absolutely sure of his intellect and ability to articulate his views in an utterly distinctive manner, always considered himself a star.

“Monday Night Football” merely made it indisputable, and in turn he helped make “MNF” what it would be – setting a high bar for engagement that was hard-pressed to match in later years and after a move to cable.

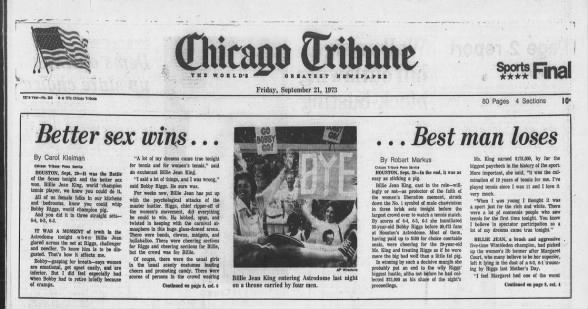

King beats Riggs in tennis battle of the sexes — Sept. 20, 1973

“Better sex wins…”

The mythology has grown to match the inspirational symbolism of Billie Jean King’s prime-time Battle of the Sexes tennis victory over Bobby Riggs in the Houston Astrodome on Sept. 20, 1973.

At the time, however, King’s 6-4, 6-3, 6-3 win and all the hoopla surrounding it made for only the second-highest rated show on TV that night.

The Tribune sent two writers to Texas to cover the spectacle: Carol Kleiman, referred to as “our gal” in the headline of a preview piece she wrote, and Robert Markus, who datelined one advance column “Hogstown.”

They had dueling front-page accounts of King’s salvo against male chauvinist pigs everywhere.

“Bobby – gasps for breath – says women are emotional, get upset easily and are inferior,” Kleinman wrote. “But I did feel especially bad when Bobby had to retire briefly because of cramps.”

Said Markus: “In the end, it was as easy as sticking a pig.”

Markus reported Riggs, then 55, got $75,000 for the made-for-TV event – equivalent to roughly $430,000 today – but that figure doesn’t include the thousands more he received for promoting a candy brand on his warmups.

As winner, King, 29, “earned $175,000, by far the biggest paycheck in the history of the sport.” (That would be $1 million in 2020.)

There’s no denying the King-Riggs match captured the nation’s imagination, and it certainly looms large for its role in fueling the ambitions of a generation of women, maybe more.

Yet for all that, the movies made about it and the event’s place in collective pop culture consciousness, it may be surprising CBS’ airing of the 1967 film “Bonnie and Clyde” outdrew King-Riggs on ABC.

Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway were watched in 33.5% of American television households, according to Nielsen. King and Riggs were seen in 28.1%.

They would finish No. 1 and No. 3, respectively, in the weekly standings, with an “All in the Family” episode wedged in between.

The tennis audience was definitely passionate. Chicago’s WLS-Ch. 7 was flooded with more than 600 calls during match coverage.

Although a handful were the usual gripes about ABC announcer Howard Cosell being a loudmouth, the vast majority were complaints about analyst Rosie Casals.

It’s very possible viewers simply weren’t accustomed to hearing color commentary from a woman. But men and women alike reportedly carped about Casals, King’s regular doubles partner, calling her “bitter,” “disparaging,” “nauseating” and “biased.”

“Compared to her, the people thought Howard Cosell was an angel,” an operator told the Tribune.

President Garfield dies — Sept. 19, 1881

“He is dead”

President James Garfield, shot by an unsuccessful office-seeker 11 weeks earlier, died on Sept. 19, 1881, having served in the White House only half a year.

Garfield, 49, died in New Jersey, where he was being treated.

It initially was expected Garfield would survive Charles Guiteau’s assault in a Washington, D.C., train station. But one of his two wounds grew infected.

Vice President Chester Alan Arthur ascended to the presidency.

“The President died at 10:35 p.m.,” the Tribune reported, noting that in the afternoon Garfield’s pulse had been between 102 and 106 beats per minute and strong.

“About 35 minutes before his death, and while asleep, his pulse rose to 120 and was somewhat more feeble. At 10 minutes after 10 o’clock, he awoke, complaining of severe pain over the region of his heart, and almost immediately became unconscious and ceased to breathe at 10:35.”

Guiteau, surprised Arthur would not pardon him, was tried and ultimately hanged two days shy of the first anniversary of his attack.

Garfield had been a compromise candidate the Republicans nominated on the 36th ballot at their 1880 convention in Chicago. He later edged his Democrat rival, fellow Civil War leader Winfield Scott Hancock.

The political marriage of Garfield and Arthur was tense. When Arthur’s vice presidential duties in the Senate concluded for the session, he went home to New York for the summer of ’81 and declined to return to Washington after Garfield was shot, even as the President’s condition deteriorated.

Upon learning Garfield was dead, Arthur had a New York Supreme Court judge administer the presidential oath of office.

But Arthur didn’t return to Washington until the 21st. There he had a second oath administered by U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Morrison R. Waite on the 22nd just to ensure its legality.

While Garfield’s time in office was short, his legacy includes re-asserting presidential authority to make appointments despite efforts by Senators to wrest away that power, cleaning up Post Office corruption and advocating for civil rights for Blacks.

“By the side of the name of Abraham Lincoln, the American people now reverently inscribe that of James Abram Garfield – two great names that will live forever in history,” a Tribune editorial said.

“As they mourned Lincoln, they will mourn Garfield, with a feeling of reverential tenderness; with gratitude for the example of his lofty, pure life; with pity for his cruel, untimely death.

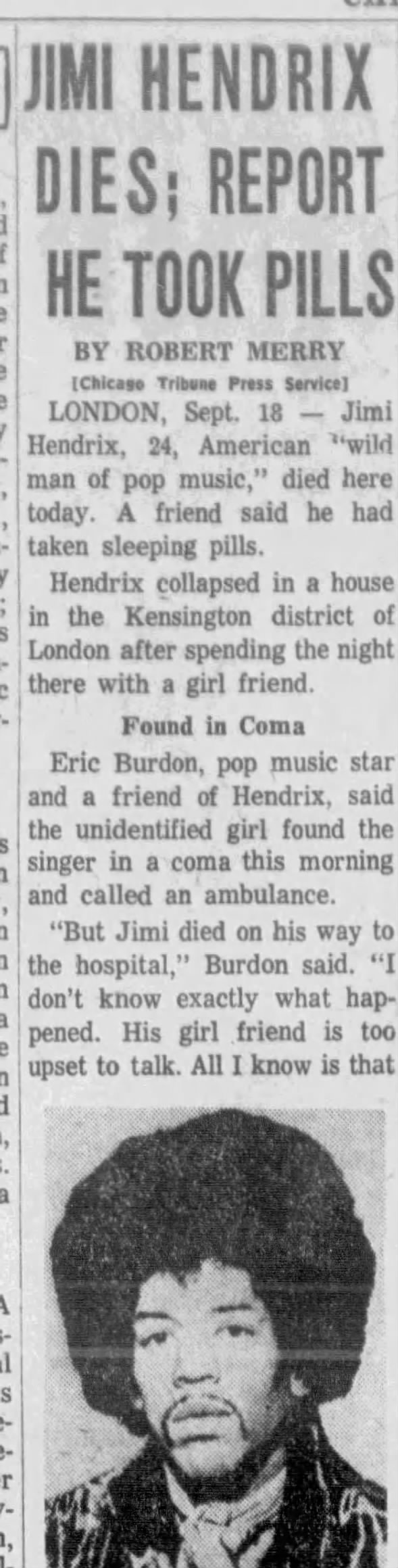

Jimi Hendrix dies — Sept. 18, 1970

“Jimi Hendrix dies; report he took pills”

There remain uncertain details about the death of transcendent rock guitarist Jimi Hendrix in London on Sept. 18, 1970.

The Chicago Tribune’s brief next-day coverage 50 years ago doesn’t clarify much. It managed to botch Hendrix’s age, which was in fact 27, not 24.

After a night that included drinking and amphetamines, Hendrix took sleeping pills, then choked on his own vomit as he slept in the apartment of girlfriend Monika Dannemann, a German figure skater.

Accounts by Dannemann, who died in 1996 at age 50, changed somewhat over time, contributing to confusion. But the sleeping pills apparently were prescribed to her and Hendrix too far too many.

The coroner’s report at the time said the circumstances of Hendrix’s death were unclear, however.

Scotland Yard was persuaded to reexamine the case in the early 1990s, but its inquiry again proved inconclusive and it was decided not to proceed.

Major media outlets that generally might be considered stodgy nevertheless eulogized the artist behind “Purple Haze” and “The Wind Cries Mary” as well as searing covers of “Hey Joe,” “All Along the Watchtower” and “The Star-Spangled Banner” in glowing terms.

But the Tribune’s London correspondent, Robert Merry – and likely the Tribune of 1970 – did not seem to fully appreciate Hendrix’s genius.

Merry’s report of the death, not quite three weeks after Hendrix played the Isle of Wight festival, reads like someone’s parent recalling a young neighbor who was too loud too late at night.

“The older generation often condemned his stage act as ‘obscene,'” Merry wrote of Hendrix. “Older persons particularly disliked what they called his ‘blatant sexualism’ on stage.

“They also could not understand why Hendrix smashed all the amplification equipment at the end of his show. They also wondered why Hendrix sometimes played the guitar with his teeth rather than his fingers.”

To be fair, many older people probably did. His music did not speak to them, although the report probably did.

According to Merry, Hendrix did not dispute that his music could be violent, quoting him on its therapeutic value: “By listening to violent music, our fans have a chance to get rid of their own violent feelings.”

Camp David Accords signed — Sept. 17, 1978

“2 Mideast pacts signed; basis set for further talks”

Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, after 12 days of negotiations with U.S. President Jimmy Carter at Camp David in Maryland, signed two groundbreaking agreements at the White House on Sept. 17, 1978.

The Camp David Accords earned Begin and Sadat the Nobel Peace Prize and, combined with the 1979 peace treaty for which the accords paved the way, reshaped the political landscape of the Middle East.

It broke the unified Arab opposition to Israel and was a defining moment in Carter’s presidency.

It redrew maps, as Israel ceded back to Egypt the territory in the Sinai Peninsula taken in 1967’s Six Day War.

It also cost Sadat his life, as a backlash from some Arabs who felt betrayed precipitated his 1981 assassination.

“The agreements trade territory for peace, providing for eventual Israeli withdrawal from the occupied territories on the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and Sinai Peninsula in return for peace and normal relations,” the Tribune’s John Maclean and Harry Kelly reported.

The United Nations General Assembly did not recognize the accords because neither it nor the Palestinian Liberation Organization were included in the process.

Tensions remain in the region and, obviously, the Palestinian conflict with Israel continues. But the 1978 agreements was impactful and historic nonetheless.

Television networks broke into their Sunday prime-time entertainment schedules for announcement of the agreements at the White House.

The Tribune said Sadat put on glasses and “spoke slowly in his resonant voice. He called it a ‘historic moment’ and praised Carter for taking ‘the gigantic step’ to call the summit despite the high risks. He thanked all Americans. He did not mention Begin.

“Begin did not read from notes. He was relaxed. He seemed almost joyful. He said ‘the Camp David conference should be renamed. It was the Jimmy Carter Conference.'”

Not everyone was wowed, but they were less peeved from a geopolitical standpoint than the fact their TV stations thought it demanded live coverage.

“The angriest viewers were apparently those who were watching Part II of the movie ‘King Kong’ on WMAQ-Ch. 5. More than 100 viewers called the station to complain, said a spokesman. ‘A lot of people were mad because they would have to keep their kids up later,’ he said.”

Newspaper publishes H-bomb info — Sept. 16, 1979

“Tribune to excerpt letter on H-bomb”

The Madison Press Connection, in defiance of a court order branding its information “secret restricted data,” published a letter that used publicly available information to detail how a hydrogen bomb works on Sept. 16, 1979 – and the Chicago Tribune would soon follow suit.

Federal lawyers a day earlier had obtained an order barring the Daily Californian of Berkeley, Calif., from running the letter by Charles Hansen, a computer programmer with two years of college education in mechanical engineering, to U.S. Sen. Charles Percy, an Illinois Republican.

The Tribune did not think there was anything in the letter that constituted a security risk and felt the government was violating the First Amendment. The newspaper explained it was announcing its intent to publish the letter in another two days to allow for court challenges it was confident it would win.

But the federal government surprised everyone, withdrawing its objections the next day, so the Tribune published the letter a day earlier than planned over two inside pages.

“We do not believe this letter contains secret information that would jeopardize national security,” Tribune Publisher Stanton Cook had said in a statement. “We are confident that the information was assembled from records available to any researcher.

“We do not believe that secrets shared by five other nations including Soviet Russia are secure in any circumstances. We believe that the government’s attempts to prevent publication of this and similar papers represent a dangerous and unprecedented threat to the First Amendment guaranteeing free speech and a free press.”

The U.S. government six months earlier had stopped The Progressive, another Madison-based publication, from running a freelance story on H-bomb data based on public documents.

The government’s aggressiveness – which also ensnarled a Tribune sister paper in California – led the Chicago Tribune to challenge the threatening precedents.

“Knowing how the government may intimidate and has intimidated small publishers, we have chosen to commit our resources to the cause of freedom in this contest,” Cook said. “Furthermore, our company already is involved since the Palo Alto (Calif.) Peninsula Times-Tribune is now the target of a government inquiry in this case.

“If the government can deny the right to publish on the flimsy grounds that have been cited so far in The Progressive Magazine case, we shall be well on our way to a system of secret government which the First Amendment was intended to prevent.”

Emboldening publishers was the fact the Hansen letter wasn’t quite the “Build a Bomb” guide some claimed or feared.

David Wagner, the Press Connection’s editorial page editor, described it to the Tribune’s Lee Strobel as “a theoretical description of how an H-bomb work; it’s not a recipe or how-to-do-it manual. … You can’t build an H-bomb from reading this darn thing.'”

Part of the letter, Wagner said, was dedicated to “a lot of political commentary about the classification policies of the federal government.”

A subsequent Tribune editorial suggested that had the Progressive been allowed to publish its less-detailed story, there would have been less of a to-do and Hansen probably wouldn’t have written his letter.

“If it does nothing else,” Cook said, “the Hansen letter demonstrates that the so-called ‘secret’ the government says it is trying to protect is a myth.”

Four girls killed in Klan bombing of Birmingham church — Sept. 15, 1963

“Bomb Negro church; 4 die”

Ku Klux Klansmen bombed Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church, killing four girls attending Sunday school and injuring at least 21 others among nearly 400 worshipers on Sept. 15, 1963.

“These children – unoffending, innocent, and beautiful – were the victims of one of the most vicious and tragic crimes ever perpetrated against humanity,” Dr. Martin Luther King would say in his eulogy at the funeral for three of the victims. “And yet they died nobly. They are the martyred heroines of a holy crusade for freedom and human dignity.”

That funeral, three days after the blast and three weeks after King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington, underscored just how much resistance the civil rights movement faced and what the stakes were.

King had used the 16th Street church, three blocks from City Hall and facing Kelly-Ingram Park, as his headquarters during a spring desegregation demonstration earlier that year.

Killed were Cynthia Wesley, 14; Carol Robertson, 14; Addie Mae Collins, 14, and Denise McNair, 11.

“Sunday school teachers said the 80 youngsters had begun to gather in the assembly room for closing prayers after attending classes in other rooms,” the report in the Tribune said. “The bomb went off in a room next to the assembly room, at 10:22 a.m., shattered the partition and sent much of its force into the room where the children were.”

The FBI by 1965 would identify the white supremacists who used a timer and dynamite to bomb the church. It was the work of four members of a Klan splinter group called the Cahaba Boys.

But none of the men – Thomas Edwin Blanton Jr., Herman Frank Cash, Robert Edward Chambliss and Bobby Frank Cherry – would face prosecution in the case until 1977, when Chambliss was convicted in the first-degree murder of McNair.

There was an effort to pick up some old civil rights era cases around the turn of the century, however.

With future U.S. Senator Doug Collins among the prosecutors, Blanton in 2001 and Cherry in ’02 were convicted of four counts of murder each and received life sentences. (Cash had died in 1994.)

Among those who knew the girls killed in the blast was future U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, who was 8 years old at the time and both a friend and school mate of McNair, the youngest victim.

President Barack Obama awarded a posthumous Congressional Gold Medal to each of the four victims in 2013.

“That horrific day … quickly became a defining moment for the Civil Rights Movement,” Obama said a few months later on the 50th anniversary of the incident. “It galvanized Americans all across the country to stand up for equality and broadened support for a movement that would eventually lead to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.”

Grace Kelly dies — Sept. 14, 1982

“Princess Grace is dead at 52”

From Philadelphia to Hollywood to Monaco, where she became an actual princess, Grace Kelly lived a storybook existence until the end.

She died on Sept. 14, 1982, a day after a car she was driving plunged 120 feet off a mountain road in France. She was 52.

The youngest of her three children with Monaco’s Prince Rainer III, 17-year-old Princess Stephanie, survived the crash with a concussion and hairline fracture in the vertabra of her neck.

Tribune science editor Ronald Kotulak reported it was likely Grace suffered a stroke just before her accident, and in fact it would later be reported Stephanie unsuccessfully tried to get control of the car from her mother before it left the road.

Nothing in initial reports of the car accident suggested the seriousness of the princess’ condition. All that was said was that she had broken ribs, a thighbone and collarbone, but her condition apparently grew more serious. The prince decided to take her off life support.

“At the end of the day, all therapeutic possibilities had been exhausted and Her Serene Highness, the Princess Grace, died of an intracerebral vascular hemorrhage at 22:30 (3:30 p.m. Chicago time),” the palace statement said on the Tribune’s front-page report.

News of the death, according to the report, “shocked the municipality on a rocky slice of the French Riviera and stunned movie fans, who never stopped loving her even after she left them” for a dashing prince and his tony, tiny state in 1956.

Born one of four children to an athletic, successful Philadelphia family – dad was a millionaire contractor, mom a one-time model – Kelly defied her parents in pursuing an acting career.

She segued from the New York stage to television to movies, where her work would earn the No. 13 slot on the American Film Institute’s 2005 list of top film legends despite a relatively brief career of 11 pictures over six years.

Among her best-known::

– Fred Zinnemann’s “High Noon” (1952) with Gary Cooper;

– John Ford’s “Mogambo” (1953) with Clark Gable and Ava Gardner, which earned the future princess a Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination in 1954;

– Alfred Hitchcock’s “Dial M for Murder” (1954) with Ray Milland;

– George Seaton’s “The Country Girl” (1954) with Bing Crosby and William Holden for which she won an Oscar in 1955 as Best Actress;

– Hitchcock’s “To Catch a Thief” (1955) with Cary Grant;

– Hitchcock’s “Rear Window” (1954) with James Stewart;

– And Charles Walters’ “High Society” (1956) with Crosby and Frank Sinatra.

It was while making “To Catch a Thief” on the Riviera that she met Prince Rainer Louis Henri Maxence Bertrand Grimaldi, heir to Europe’s oldest royal family, sovereigns of Monaco dating back to 1297.

The courtship continued quietly until her engagement was announced while she worked on “High Society.” A week after the musical adaptation of “The Philadelphia Story” wrapped, she set sail for her wedding ceremonies in Monaco.

“I fell in love with him, but what followed was a good deal more difficult than I thought,” the princess said years later. “There was a foreign language to learn, a new country and a life totally different to anything I knew before. … Even getting used to marriage took time.”

Prince Rainer lived on more than 22 years after Grace’s death, dying in 2005 at age 81. He never married again.

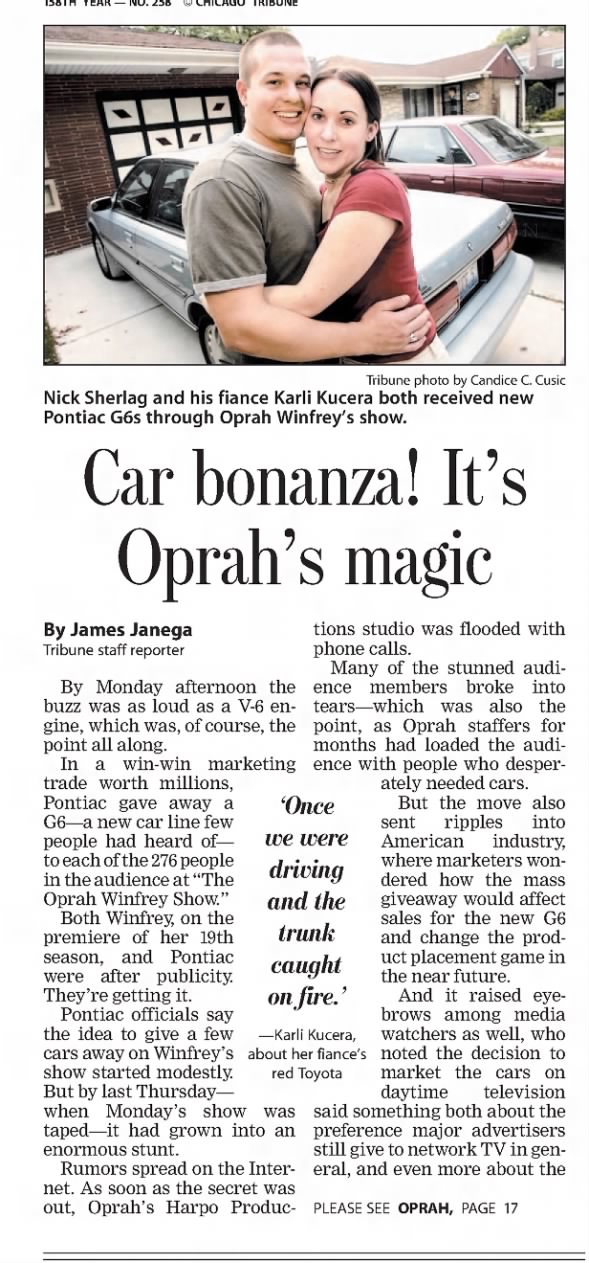

Oprah Winfrey gives cars to 276 people in studio audience — Sept. 13, 2004

“Car bonanza! It’s Oprah’s magic”

“The Oprah Winfrey Show” opened its 19th season on Sept. 13, 2004, and the phrase “You get a car!” entered the national lexicon.

Only Oprah Winfrey didn’t just say, “You get a car!”

A check of the video indicates that what she said was: “You get a car! You get a car! You get a car! You get a car! You get a car! You get a car! You get a car! You get a car! Everybody gets a car! Everybody gets a car! Everybody gets a car! Everybody gets a car! Everybody gets a G6! Everybody gets a car! Everybody gets a car! Oh, my goodness! Everybody gets a car! You get a car! You get a car! You get a car! You get a car! Everybody gets a car!”

All told, each of the 276 members of Winfrey’s Chicago studio audience – selected by the show’s staff because they needed a car – erupted upon learning they had been awarded a Pontiac G6, an unforgettable daytime TV surprise stunt and a huge marketing stunt with which to launch a new model car.

Teeing it up, Winfrey had given away 11 cars earlier in the program.

“We’re calling this our ‘wildest dreams’ season because this year on the ‘Oprah’ show, no dream is too wild,” Winfrey said. “No surprise is too impossible to pull off and it can happen anywhere at any time to anybody. Maybe even you.”

Then she announced there was one more car to give away, and women with gift-wrapped boxes on silver trays were sent in the audience. Everyone was given a box and told to open in on Oprah’s cue. She told them only one held a key to the vehicle.

But they all did, and pandemonium ensued.

“You get a car!” is a lot more exciting than “You get a tax bill!” Audience members got both, but many found $6,000 for a $28,000 auto a fair exchange.

Still, some winners didn’t take the cars and others sold theirs.

Also, it turned out the cars in the parking lot outside Winfrey’s Chicago studio complex were for show. Winners had to claim their vehicles at their local Pontiac dealers.

The G6 “Oprah” promotion cost Pontiac $7.7 million in cars, but made America aware of its new mid-size replacement for the Grand Am.

Unfortunately, for all the hoopla, the general public wasn’t wowed by the G6.

Both Pontiac and the car ended their runs in 2010.

Winfrey, meanwhile, closed out her daily talk show in 2011 while it was still on top and moved full time to California, presiding over The Oprah Winfrey Network and her media and philanthropic empire from there.

The site of her old complex is now home to the global headquarters of fast-food giant McDonald’s.

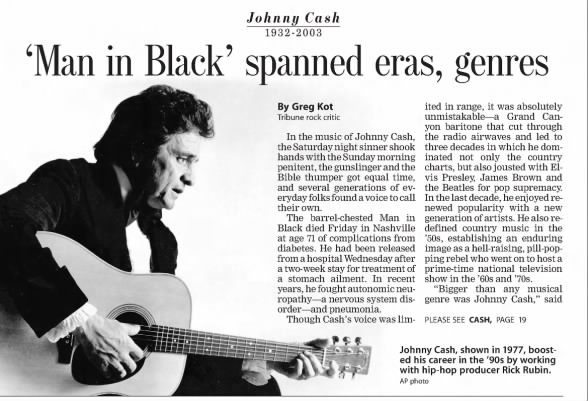

Johnny Cash dies — Sept. 12, 2003

“Man in Black’ spanned eras, genres”

Johnny Cash – the “Man in Black” whose songs and life were filled with hard times and high points, heartbreak and hope, setbacks and salvation – died of complications from diabetes on Sept. 12, 2003.

He was 71 and, in recent years, had been in poor health.

The Tribune’s Greg Kot wrote that in Cash’s music “the Saturday night sinner shook hands with the Sunday morning penitent, the gunslinger and the Bible thumper got equal time, and several generations of everyday folks found a voice to call their own.”

In Rolling Stone after Cash’s death, Bob Dylan said, “Johnny was and is the North Star,” while Bono observed: “Every man could relate to him, but nobody could be him. To be that extraordinary and that ordinary was his real gift.”

His voice, Kot said, was “a Grand Canyon baritone” that not only topped country charts but challenged pop artists and, in his last decade, resonated with a new generation.

His signature sound was “a stoic voice that moved with unhurried cadence of everyday speech, and a sparse, train-chugging rhythm that blurred the boundaries between country, blues and rock ‘n’ roll.”

His signature songs spanned a wide spectrum of humanity and sentiment.

There was a killer’s lament (“Folsom Prison Blues”) and wry regret of legacy (Shel Silverstein’s “A Boy Named Sue”). There was also that unsettling but authentic ride of coming off a bender (“Sunday Morning Coming Down,” an early break for Kris Kristofferson) set against incongruous orchestration. Romantic fidelity (“I Walk the Line”) was matched by the familiar bickering of an old couple (“Jackson,” a duet with his second wife).

The child of sharecroppers, Cash battled addictions and dark moods, as depicted in the 2005 film “I Walk the Line” starring Joaquin Phoenix and Reese Witherspoon.

His life was probably saved by his 1968 marriage to June Carter, who was born to country royalty as a member of the pioneering Carter family, and insisted he clean up.

Both were married to others when they met and “Ring of Fire” was born of their passion. (Roseanne Cash, his daughter and a star in her own right, was a child of his first marriage.)

Cash, who had found common ground with those protesting the Vietnam War, enjoyed a late-in-life rebirth in collaboration with rap producer Rick Rubin.

Their collaboration brought Cash to new audiences and greater appreciation with stripped-down but powerful recordings, such as his cover of Nine Inch Nails’ “Hurt.”

Through it all, he wore his trademark black suits. While he explained in song the suit was “just so we’re reminded of the ones who are held back,” that came after the fact.

The truth is that Cash found early in his career, traveling from city to city and show to show, he found black clothing easier to keep clean.

America attacked — Sept. 11, 2001

“Our nation saw evil”

There is a line in recent U.S. history of before the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and everything after.

No one old enough to remember needs to be reminded of the details and the generation that’s matured since is well-schooled on it.

So, the next day’s Tribune detailing those horrible events is less an education than an artifact. It makes old emotions fresh.

No additional words are necessary.

It’s the product of a clear-headed newsroom setting everything but duty aside to record what so many saw with their own eyes on live TV, take stock of the moment and cautiously attempt to look ahead.

This is what history looks like when the ink is barely dry.

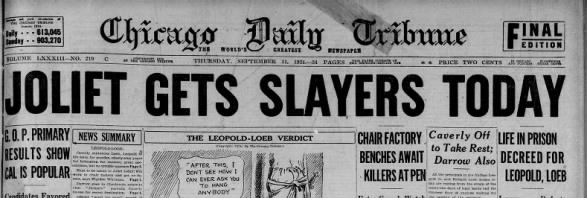

Leopold and Loeb given life sentences — Sept. 10, 1924

“Joliet gets slayers today”

Nathan Leopold Jr. and Richard Loeb, a pair of well-to-do University of Chicago students who kidnapped and a murdered a 14-year boy in the mistaken belief they were so smart they could pull off a perfect crime, were spared the gallows on Sept. 10, 1924.

Leopold and Loeb instead were given life sentences for the murder of young Bobby Franks as well as 99-year sentences for the kidnapping by Cook County Circuit Court Judge John R. Caverly.

Their lives were effectively saved by famed attorney Clarence Darrow, whose 12-hour summation at their sentencing hearing – an argument against the death penalty and a plea for mercy – was considered perhaps the greatest of his storied career.

“Well, it’s just what we asked for but it’s pretty tough,” Darrow said of the verdict, according to the Tribune’s report. “It was more of a punishment than death would have been.”

That sentiment was not universal embraced.

Echoing the sentiments of prosecutor Robert Crowe, a front-page cartoon by John T. McCutcheon depicted the state saying to Illinois justice, “After this, I don’t see how I can ever ask you to hang anybody.”

Judge Caverly explained that a chief consideration was the youth of the defendants. Leopold was 19 at the time, Loeb 18.

“Life imprisonment may not, at the moment, strike the public imagination as forcibly as would death by hanging,” Caverly said in his decision.

Leopold and Loeb had long planned their crime, deciding Franks, a second cousin of Loeb’s, would be their victim.

On May 21, 1924, the two convinced Franks to get into a car Leopold had rented under an alias. While one of them drove, the other attacked Franks with a chisel. There was conflicting testimony as to who did what.

They disposed of the body near Hammond, Ind., having poured acid on it to obscure identifying features, then returned to the city. Leopold called Franks’ mother to demand a ransom.

With Chicago police launching a major investigation, it took a little more than a week for the subterfuge to unravel. It didn’t help Leopold and Loeb that a pair of prescription glasses that could be tied to Leopold was discovered near the recovered body.

Loeb’s family hired Darrow, a staunch opponent of capital punishment, to defend them. In 2020 dollars, he was paid more than $1 million.

Darrow decided it best to have Leopold plead guilty and seek mercy from the court, reasoning that his clients would hang if they entered pleas of not guilty by reason of insanity and faced a jury trial. The sentencing hearing ran 32 days.

The Leopold and Loeb case was not the first “crime of the century” of the 1900s and there would be others over the next 75 years or so.

Yet it clearly captured the nation’s imagination and went on to inspire such fictionalizations as Alfred Hitchcock’s “Rope,” Barbet Schroeder’s “Murder by Numbers” and an episode of TV’s “Columbo” called “Columbo Goes to College.”

Each man initially was sent to prison in Joliet and eventually to Stateville Penitentiary in Crest Hill, where Loeb would be murdered by a fellow inmate 12 years later in a prison shower at age 30.

Leopold, a model prisoner, was paroled in 1958 and died of a heart attack in 1971 at age 66.

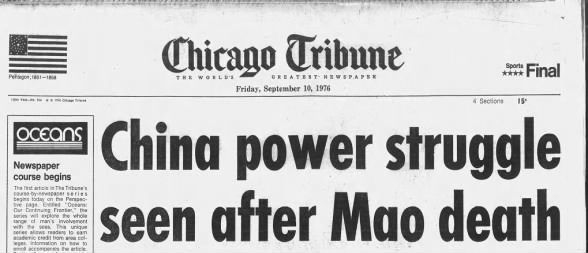

Mao dies — Sept. 9, 1976

“China power struggle seen after Mao’s death”

Mao Zedong, a farmer’s son who became the founding father of the People’s Republic of China, died on Sept. 9, 1976. As one headline put it, his long march into history had come to an end.

Mao was 82 and had led the Asian nation as chairman of the Communist Party of China since 1949, forcing out the Nationalist government and displacing it to Taiwan.

While he undeniably modernized China, helping make it a world power, he did so at a staggering human cost.

As many as 80 million citizens died because of his policies, which included absolute intolerance of opposing views. It is impossible to consider his legacy without noting mass executions and prison labor camps.

Mao’s agricultural policies in attempting to industrialize what had been a peasant state alone led to a famine that wiped out an estimated 30 million people.

“In his long life, he was many things – military leader, guiding figure of one of the bloodiest revolutions in history, organizer, poet, philosopher, and god – but most of all he was a revolutionary,” a Tribune editorial said upon his death. “From his boyhood, when he rebelled against his father, through the years of fighting and intriguing to take over China, and into his dotage, Mao was the opponent of authority.

“After his revolution, he did not weep as Alexander the Great did because there were no more worlds to conquer; instead he proclaimed the revolution was not complete; it would go on forever.

“Thus, in the 1960s, he inflamed the Red Guards and plunged China into a ‘Cultural Revolution,’ which almost turned the country upside down. Yet it eventually ended, falling far short of the thousand-year struggle he preferred.”

That, too, was a brutal, bloody, oppressive mess that did not abate until after his death.

The only authority Mao recognized was his own, which meant would-be successors often came and went, leaving a void in his absence.

“Anticipating a power struggle, the Communist Party Central Committee … called on the Chinese people to uphold the unity of the party and to ‘carry on the cause left by Chairman Mao,'” Reuters’ Peter Griffiths wrote on the Tribune’s front page.

Griffiths noted, “The Central Committee urged the people to ‘deepen the criticism of former Vice Premier Teng Hsaio-ping, toppled last April in the power struggle that followed the death of Premier Chou En-lai.”

Much as the English spelling of Mao Tse-tung would evolve, Teng Hsaio-ping would be rendered in time as Deng Xiaoping, who ultimately became the nation’s leader. And it was Deng’s execution of post-Mao vision of modern China that proved critical to establishing the nation as it now is.

Officially, China acknowledges Mao’s “gross mistakes” and has largely abandoned his economic philosophies, but he remains celebrated today.

Despite his image being oft-displayed and his red book of philosophy a prized possession of Chinese citizens, Mao was wary of the cult of personality, at least for others. He made it a requirement Chinese leaders be cremated, and that was his wish for himself. His acolytes, however, decided he should be preserved and displayed like Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin.

Mao’s mausoleum in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square is a destination for tourists and residents alike.

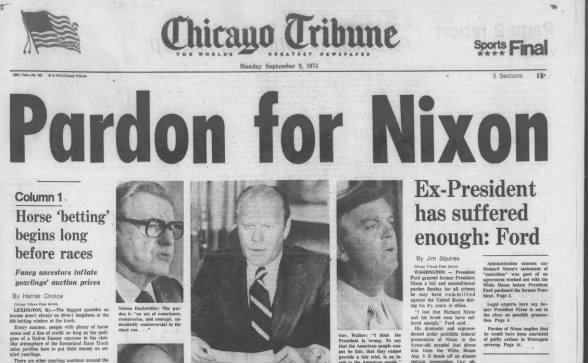

Ford pardons Nixon — Sept. 8, 1974

“Pardon for Nixon”

Thirty days after becoming the first person to assume the presidency without ever running for national office, Gerald Ford on Sept. 8, 1974, gave predecessor Richard Nixon a full and unconditional pardon for all crimes he may have committed in his 51/2 years in the White House.

“I feel that Richard Nixon and his loved ones have suffered enough,” President Ford said.

Wrote Jim Squires, a future Tribune editor: “His dramatic and unprecedented order prohibits federal prosecution of Nixon in the 2-year-old scandal that drove him from the White House Aug. 9. It heads off an almost certain prosecution for obstructing justice in the Watergate burglary and appeared certain to set off a national debate.”

Ford may have saved ailing former President Nixon – and the country – the spectacle of a trial.

But with the wounds of Watergate still fresh, it hardly brought together a divided nation and ultimately helped Jimmy Carter unseat Ford a little more than two years later.

Among those incensed was Jerald terHorst, Ford’s press secretary and long-time friend, who quit in protest over the pardon.

“The President acted in good conscience and I also found it necessary to resign in good conscience,” terHorst said in a statement read by his wife outside their Virginia home, according to the Tribune’s Aldo Beckman.

President Ford said he regretted terHorst’s resignation but understood it.

“I appreciate the fact that good people will differ with me on this very difficult decision,” Ford said. “However, it is my judgment that it is in the best interests of our country.”

Nixon issued a six-paragraph statement in which he conceded “mistakes and misjudgments” in the Watergate affair but did not admit guilt.

Fairly or not, some didn’t think the pardon passed the smell test, and it didn’t help that Ford lacked the mandate an election to high office might have given him.

Ford was House minority leader from Michigan when Nixon, already mired in the Watergate scandal, nominated him to fill the vacancy left by Vice President Spiro Agnew’s resignation in late 1973.

Agnew had been indicted and eventually pleaded no contest to tax evasion and money laundering charges connected to bribes he accepted while governor of Maryland.

At Ford’s Senate confirmation hearing en route to the vice presidency, he was asked whether he might someday issue a pardon to Nixon.

“I do not think the public would stand for it,” Ford responded.

Yet once Ford had done so, Republican Sen. Barry Goldwater said pardoning Nixon “was the only decent and prudent course.”

Democratic Sen. Robert Byrd, however, said it suggested “one standard for the former President of the United States and another standard for everybody else.”

Curiously, while the Nixon pardon was the most historic thing to happen on that particular Sunday, it was not the only memorable, quintessentially 1970s event.

Daredevil Evel Knievel earned his own front-page real estate by failing to jump the Snake River Canyon in Idaho. A parachute in Knievel’s rocket-powered “Skycycle” cycle opened prematurely. He crashed into the canyon’s wall, landed on a ledge by the river some 600 feet below the rim, and emerged with cuts and bruises.

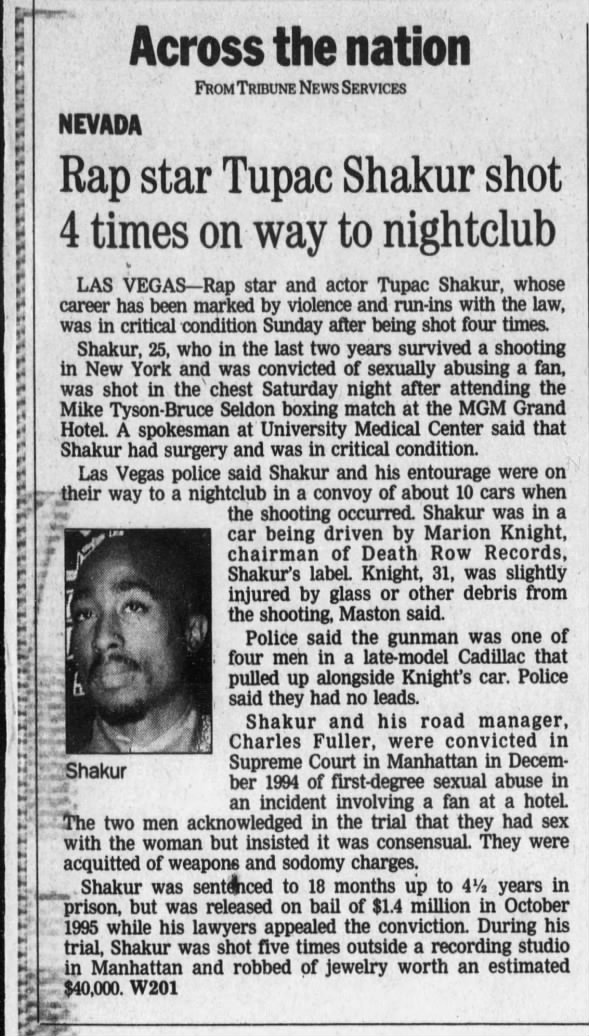

Tupac Shakur shot — Sept. 7, 1996

“Rap star Tupac Shakur shot 4 times on way to nightclub”

Rap star and actor Tupac Shakur was shot four times in a drive-by shooting on the Las Vegas Strip while en route to a night club after the Mike Tyson-Bruce Seldon fight at MGM Grand Hotel on Sept. 7, 1996.

Shakur, 25, died six days later.

The gunman has never been captured.

Though his career was short, Shakur remains one of rap’s most influential artists 24 years later.

His songs addressed social issues but weren’t always easy to categorize. He could be supportive of women in some, but come across as misogynistic in others.

The child of Black Panther activists who studied at a Baltimore arts school before moving to California, Shakur’s recordings sold 75 million copies worldwide and he was inducted in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2017, his first year of eligibility.

His acting career included star turns in films such as “Poetic Justice” opposite Janet Jackson.

“The chronicle of Shakur’s success as a music star ran on a parallel track with his criminal record,” the Tribune’s Vincent J. Schodolski wrote in Shakur’s obituary.

“Between 1991 and 1995, Shakur was involved in increasingly serious brushes with the law as he built his career with Grammy-nominated songs like ‘Same Song’ and was part of the Digital Underground’s 1991 album ‘Sons of the P.’ At the same time Shakur scored his first major individual success with an album called ‘2Pacalypse Now.'”

Vice President Dan Quayle cited that album as part of what he said was the entertainment industry’s assault on traditional family values.

“In 1993,” Schodolski wrote, “just as one of his strong-selling albums was earning him fame and fortune, Shakur was arrested three times, twice for assaults and once for allegedly holding a woman down while his friend sodomized her. Though he denied involvement in the latter crime, he was convicted.

“In 1994, Shakur was arrested, arraigned or tried a dozen times on a variety of assaults, parole violations and sexual assault.”

Then in November 1994, he was wounded five times outside a Manhattan recording studio and robbed of $40,000 worth of jewelry.

Songs such as “Death Around the Corner” and “If I Die 2Nite,” from 1995’s “Me Against the World,” almost seemed to foreshadow what still lay ahead.

Less than two years later, Shakur was wounded in Las Vegas by someone in a white Cadillac while riding in a black BMW sedan driven by Marion “Suge” Knight, chairman of Death Row Records, Shakur’s label.

Hours earlier, Shakur and members of his entourage fought with a group of men. The confrontation had gang implications.

A two-part 2002 Los Angeles Times report by Chuck Philips, the product of a one-year investigation, reported the murder was the work of the Southside Crips, a Compton, Calif. gang, in retaliation for the fight that night.

The paper said Orlando Anderson, whom Shakur had beaten, fired the fatal shots and that Las Vegas police bungled the investigation.

Anderson, who denied involvement in Shakur’s murder and was never charged in connection with it, was killed in 1998 in an unrelated gang shooting.

President McKinley shot — Sept. 6, 1901

“Attempt to Murder President McKinley”

President William McKinley was shot twice in the abdomen at point-blank range by anarchist Leon Czolgosz at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, N.Y., on Sept. 6, 1901.

McKinley, 58, initially appeared to be recovering but one of the wounds showed signs of infection a week later and he died of gangrene on Sept. 14.

Theodore Roosevelt, 42, who had only become vice president with the start of McKinley’s second term six months earlier, succeeded him.

The top of the initial coverage in the Tribune reads a bit like a Twitter feed.

On the very top, a dispatch notes McKinley’s five physicians reporting, “The President is rallying satisfactorily and is resting comfortably” at 10:50 p.m. with a temperature of 100.4, a pulse of 124 and respiration of 24.

Then came a bit from George Cortelyou, McKinley’s personal secretary, who gave an account of the assassination attempt around 4 p.m., the injuries incurred, the surgery performed and how the President was doing.

After that was a more traditional news report.

There reportedly were 3,000 people in the Temple of Music when McKinley was shot with another 20,000 outside waiting for the chance to enter and shake hands with him.

Czolgosz had turned to anarchism after losing his job as a steelworker in the depression of 1893. He bought a .32 caliber gun just a few days before his attack on McKinley, and followed McKinley around the fair on Sept. 5, but he didn’t feel he could get a clean shot off.

Cortelyou, wary of security at the Temple of Music, twice tried to take the meet-and-greet on the 6th off the President’s schedule. McKinley dismissed the safety concerns and insisted on going through with it.

When Czolgosz got to the front of the line and face-to-face with McKinley, the President extended his hand. Czolgosz knocked it away and shot him twice but was stopped before he could get off a third round.

One bullet, deflected by a coat button, only grazed McKinley. The other lodged in his gut.

McKinley was the third of four U.S. Presidents felled by an assassin’s bullet, following Abraham Lincoln and James Garfield and preceding John Kennedy.

Czolgosz, 28, who said he “thought it would be a good thing for the country to kill the President,” died in the electric chair just 45 days after McKinley’s death.

The Munich massacre at the Olympics — Sept. 5, 1972

“11 Israelis Slain”

Wearing track suits and carrying duffels filled with weapons, eight Palestinian terrorists from the group Black September snuck into the Olympic Village at the Munich Summer Games in the early morning of Sept. 5, 1972.

After a hostage situation capped by an airport shootout at day’s end, minutes after midnight, five Israeli athletes and six Israeli coaches had been massacred.

“The Olympic ideal of peace and friendship was drowned in a river of blood,” Tribune sports writers Cooper Rollow and Robert Markus wrote.

A West German police officer also was killed, along with five of the terrorists.

The Olympics continued for a time during the hostage crisis despite the Israeli government requesting that the games be halted. Eventually the competition would be suspended for 34 hours.

A memorial service was staged in the Olympic Stadium at which International Olympic Committee President Avery Brundage did little to dispel the notion he had anti-Semitic sympathies by minimizing what happened to the Israelis.

Brundage faced criticism both for his remarks – which put the Israeli massacre on par with debates over amateurism as well as not allowing Rhodesia to compete because of its racism – and pushing to resume the games.

But the horror show on the world stage was hard to downplay, much as Brundage may have tried.

“The terrorists climbed an eight-foot fence, battered down the door of the Israeli quarters, and shot to death an Israeli wrestling coach, Moshe Weinberg,” Rollow and Markus wrote. “Weinberg’s body was dragged into a hall and later removed to a local hospital, where it was identified by his mother, a Munich resident.

“Josef Romano, a weight lifter, also was wounded mortally in the attack and the Arab activists announced they would kill the other nine hostages unless their demands were met.”

The terrorists periodically beat their captives as the long day wore on.

Rollow, the Tribune’s sports editor, talked his way into the village where he lay on his stomach next to ABC’s Howard Cosell on a hillside, awaiting a shootout with police that never happened.

The terrorists saw snipers assuming attack positions on live TV coverage, causing the mission to be aborted.

Israe flatly refused to negotiate with the terrorists. West German officials talked with the captors through the day, eventually saying they would give the group a chance to leave the village for a military airport and a flight to Cairo.

A series of mistakes, both in strategy and in execution, caused the planned ambush to go awry, resulting in the remainder of the deaths at the airport.

Initial reports stated the airport effort had succeeded and, for viewers in the United States, it was left to ABC’s Jim McKay to relate the sad news near the end of prime time in much of the country.

“You know, when I was a kid, my father used to say, ‘Our greatest hopes and our worst fears are seldom realized,'” McKay told America. “Our worst fears have been realized tonight. They’ve now said that there were 11 hostages. Two were killed in their rooms yesterday morning, nine were killed at the airport tonight. They’re all gone.”

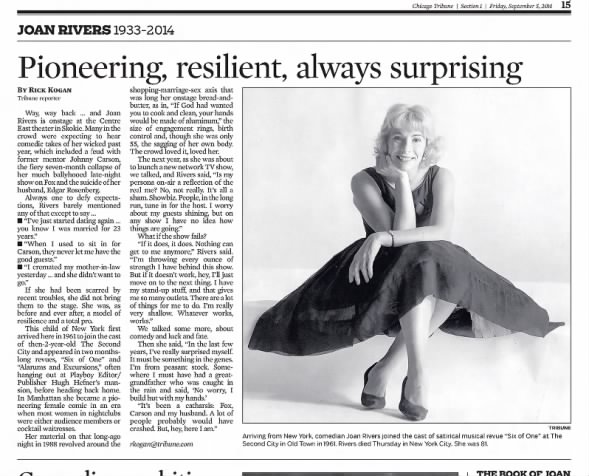

Joan Rivers dies — Sept. 4, 2014

Rick Kogan remembrance

Joan Rivers, an alumna of Chicago’s Second City who became a tireless stand-up comedian, TV host, actress, writer and home shopping saleswoman, died on Sept. 4, 2014.

Rivers had been hospitalized for a week since suffering major complications during what was supposed to be a minor surgical procedure at an outpatient clinic.

The woman who used to joke that she’d had “so much plastic surgery that when I die, they’ll donate my body to Tupperware” was 81.

Rivers’ humor didn’t just revolve around what the Tribune’s Rick Kogan referred to as “the shopping-marriage-axis,” but played off her audience’s fascination with celebrities, and her determination to demythologize them.

Rolling Stone ranked Rivers sixth on its 2017 list of the 50 best stand-up comics of all time, a list topped by Richard Pryor, George Carlin and Lenny Bruce. She was just below Chris Rock and just ahead of Jerry Seinfeld.

A typical joke about her sex life would be: “I asked my husband, Edgar, if this dress gave him any ideas. He said, ‘Yes, I’d like to see my girlfriend in it.'”

Regarding the fictional bed-hopping character she created, Heidi Abromowitz: “She is a tramp. Her towels say His and Herpes.”

As a comic and as a late-night TV host, Rivers (born Joan Alexandra Molinsky) is remembered for pushing boundaries in fields dominated and controlled by men.

Johnny Carson had championed her stand-up career and, by the 1980s, Rivers had become his permanent guest host, filling in on NBC’s “The Tonight Show” eight weeks a year. She was considered by many his heir apparent, but perhaps not within NBC.

When Rupert Murdoch’s nascent Fox network offered her a late-night show of her own, she took it. NBC and Carson considered this, and her failed attempt to hire away a top “Tonight” producer, a betrayal. Carson never spoke to her again.

Her Fox program was a bust and she was fired after only eight months.

Her life and career went into a tailspin. Shunned by a segment of the industry, she was reeling even before her husband’s suicide – which would be dramatized in a TV movie starring Rivers and her daughter – but Rivers persevered.

She continued to perform where she could, launched a jewelry line on home-shopping television and found other TV opportunities.

Her career was expanded and extended when E! Entertainment Television put her on its red carpet at awards shows, where she dispensed with traditional niceties and instead said and asked the things viewers at home may well have said among themselves.

“Rivers zinged the stars for wearing clothes she deemed atrocious and didn’t mind taking other potshots, too,” said the Los Angeles Times’ obituary the Tribune published. “Of the habitually dour Tommy Lee Jones, Rivers said, ‘He makes Hitler look warm and funny.’

“Her criticisms often got her in trouble with some of Hollywood’s biggest stars, like Jennifer Lawrence, who said Rivers’ E! show ‘Fashion Police’ teaches young people ‘that it’s OK to point at people and call them ugly and call them fat.'”

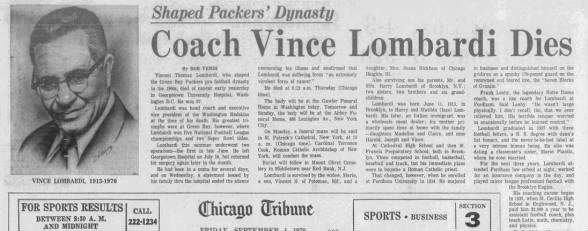

Vince Lombardi dies — Sept. 3, 1970

“The Lombardi I Knew…””

Vince Lombardi, the archetype of a hard-driving football coach who pushed the Green Bay Packers to victory in the first two Super Bowls and eventually had the championship trophy named for him, died of cancer 50 years ago on Sept. 3, 1970.

He was 57.

Tribune sports editor Cooper Rollow, who got to know Lombardi well, described the coach as “sensitive, moody, independent, sentimental. And a winner in every way.”

Rollow wrote, “Lombardi was a creature of moods and he played no favorites. When his disposition was sunny and you were favored by his company, you were the greatest. When he was feeling uptight, there was no end to his wrath. … (He) could be a tyrant all right. He could be a madman and a slave driver. He could also be a saint.”