Rescue Off Halifax

FARLEY MOWAT, author of PEOPLE OF THE DEER and THE DOG WHO WOULDN’T BE, is a Canadian who likes to track down true stories. In this second excerpt from his new book, GREY SEAS UNDER, to be published this month by Atlantic-Little, Brown, he records the exploits of a doughty and unsinkable deep-sea tug.

GREY SEAS UNDER

BY FARLEY MOWAT

The last full year of war in the North Atlantic was as busy a time for the salvage tugs as any which preceded it. During the twelve months from May of 1944 until May of 1945, Foundation’s tugs rescued twenty-two ships from sea and shore. Five of these were torpedo victims, for the U-boats remained active along the Canadian and Newfoundland coasts well into the spring of 1945.

Foundation itself had never been more muscular. Its salvage fleet consisted not only of the Aranmore, Franklin, Security, and Ocean Eagle, but in addition it now owned the Lord Strathcona and the Traverse, for in late 1944 it bought up its last major rival in home waters, the Quebec Wrecking and Salvage Company. The harbor tugs now numbered fourteen vessels, and the ancillary equipment, consisting of lighters, derrick boats, water boats, and barges, had become truly a formidable fleet. But despite its size the heart and soul of it remained with two vessels and their crews: Franklin and Aranmore. Between them they continued to do the lion’s share of the work.

By the end of 1946, great changes were in the making at Foundation Maritime. The company had learned that the British Admiralty was offering one of its famous Bustler-class tugs for longterm charter. The vessels of this class were built during the final years of the war, and they were designed to be the most powerful and efficient salvage tugs afloat. Twelve-hundred-tonners powered by twin diesels that developed thirty-fivehundred horsepower, they could cruise at sixteen knots and stay at sea under full power for thirty days. In the new tradition of our times they were completely mechanized, for all their gear was run by electricity. They were handsome vessels with something of the dash and flair in their appearance which is the hallmark of fast naval craft.

The opportunity to charter one of these new ships, combined with the growing feeling in the executive branch of the company that Franklin had outlived her time, proved irresistible.

So Foundation Maritime acquired H.M.S. Samsonia. Under the name of Foundation Josephine she hoisted the red ensign of the Canadian Mercantile Marine in late December. She bore that name for the next five years, and during that time she was to build a magnificent reputation. Ranging the Atlantic from the coasts of Britain south to Portugal, west again to the Bahamas, and north to Labrador, she wrote a record that came close to equaling the one which had been written by the vessel she displaced.

With the arrival of Foundation Josephine, the Franklin’s fate was settled. It was inevitable that she would have to go. The days of the rough, hard little vessels like the Franklin were coming; to an end the wide seas over. But what was more tragic was that this also applied to the kind of men who had made Franklin great. They were being supplanted by a new breed, able enough, but men who were more and more technicians and less and less seamen. Franklin's people were becoming anachronisms too.

While Josephine dashed out at sixteen knots and earned the banner headlines, Franklin grew dingier and faded further into obscurity. She was kept in commission — barely — but she was given only the trivial and unwanted jobs to do; the jobs that offered little prospect of success or, if successful, that gave little hope of profit.

CHRISTMAS, 1947, came, and then a January that was memorable in the annals kept by meteorologists but which was of such a violent nature that the men who had to cope with the weather preferred to put the memory of it out of mind. It was a brutal period in the North Atlantic. Many scheduled sailings were canceled or postponed, and many ships which did essay the passage of the Western Ocean were forced to turn about or heave to and wait for better times. Day after day new gales struggled to outdo their predecessors. When one had paled into exhaustion another rose to take its place. Conditions grew so bad that almost all the transatlantic traffic turned to the southern great-circle routes in an attempt to escape the worst of them.

Consequently Foundation Josephine was dispatched to take up station at Bermuda, where she could be handy to the southern tracks. Her departure left Halifax and the northern reaches devoid of salvage or rescue ships, for the Lillian, a new diesel tug purchased from the U.S. Navy in November, had proved herself temperamental and a score of baffled technicians had spent weeks trying to get her complicated machinery to function properly, without result. Yet in order to keep Josephine free to remain at Bermuda it was essential that the Lillian be put in service. When she balked, and balked again, her owners turned to the forgotten ship.

They brought the Franklin back to life. They did it grudgingly, and as sketchily as possible. No time or money was wasted on any but vitally essential repairs. The rest was jury-rigged or else was left undone. Four days after the order to revive her was issued, she went to sea under the command of big John Lahey, a Newfoundlander.

On January 7 Josephine had gone to the rescue of the Greek steamer Themistocles six hundred miles southeast of Halifax and, after a twenty-four hour delay because of the ferocity of the weather, she managed to connect up to the cripple and begin towing her to New York. Despite her size and power it took the Josephine thirteen days to complete the tow, and the casualty was not anchored safely in port until January 20. And Josephine herself sustained such damage from the storm that she was forced to limp back to Halifax and go into dry dock for repairs. Thus, on January 24, 1948, there was only one ocean-going salvage ship available to take up arms against the hungry sea.

EARLY on Monday morning of January 19 a vessel stood out of Newport News bound for Sweden with a full cargo of mixed freight. She was the Norwegian motor ship Arosa. She was a wellfound vessel and a handsome one, for she had been built with the sweeping sheer and the graceful lines which the Scandinavians so often give their ships. She was stanch as the Trondheim men who manned her, and neither they nor she was intimidated by the unconscionable fury of the month-long sequence of gales which had worked the North Atlantic into a primordial chaos.

The Arosa came out from the shelter of the land and laid her course along the great-circle track for full-powered steamers bound for Europe. She had chosen a good moment to begin her passage, for the winter hurricane which had sent Foundation Josephine on her eighteen-day voyage to succor the Themistocles had now blown itself out, and there was a lull in the gales. At fourteen knots Arosa’s shapely stem thrust into the heaving swells the hurricane had left behind it, and by January 22 she had made good a thousand miles of easting.

It had not been easy. Deep laden as she was, Arosa had labored in the great troughs and on the long slopes of the greybeards. The strain upon her gear had been continuous. Fatigue lay on her men and on the thudding heart of her machinery. At noon on January 22 the sky drew down, opaque and ominous, and the wind returned. It began to blow out of the worst quarter, the nor’east, and Arosa’s master knew that he was in for trouble. His ship was already battened down for weather, and there was not much more that could be done. He rang for a reduction in speed to ease Arosa’s motion, and then he, his men, and his vessel prepared to endure the mauling which must come.

With a fetch of nearly a thousand miles of open ocean in which to build up strength, the new storm-driven seas began to march down upon the old hurricane-born sea, and the turmoil which ensued flung living water high over Arosa’s bridge. Her screw came up into the froth astern, then sank into the solid depths. All night she plunged and wallowed while her diesels thundered in protest, and then at dawn Arosa’s screw turned slowly to a stop. The main reduction gears had proved unequal to the strain upon them, and the ship was dead.

Arosa’s SOS was received in New York early on the morning of January 23. It came in across a gale that had already risen to force 8, although it was still in its infancy. The weather bureau had reported a new depression coining from the south, and hurricane warnings were being broadcast. In New York there was no salvage vessel able to proceed to the Arosa’s aid, since the distance alone made it almost certain that no tug could make the journey out and back without herself becoming disabled from lack of fuel.

It took time for this to become apparent to Arosa’s agents, and it was not until a further twenty hours had elapsed that the telephone in the offices of Foundation Maritime began to ring.

As he listened to the request for a deep-sea tug, Edward Woollcombe, general manager of Foundation Maritime, gave no hint of the fact that only one of his salvage tugs was ready for action. And in his usual optimistic manner he made light of the difficulties which would be encountered in any attempt to rescue the Arosa. A Foundation tug would sail at once, he said. He did not specify which one, and il the Arosa’s agents assumed he meant the Josephine, that was no fault of Woollcombe’s.

One hour later Foundation Franklin was standing out to sea from Louisburg. The thick black smoke from her twin stacks streamed flat to the southwest as the full strength of the nor’east gale struck on her port quarter. In the pilothouse Captain Lahey laid out his course and scaled it off to the last reported position of the motor ship Arosa. The distance from Louisburg was five hundred and eighty miles.

ONCE clear of the land Franklin came down on her course bringing the wind and seas hard on her port beam. The gale was still at force 8, but it was making up and already it was laden with ice crystals. The temperature, which had stood near the freezing point earlier that morning, had now fallen close to the zero mark. As the old tug drew out from shore and the seas gained in stature, she lay down to them and began to roll as abominably as she had ever done. Lahey gave her no ease. He held her at full revolutions, for he knew that his only hope of salving the Arosa was to get to her and take her back before the combination of a new hurricane and mounting seas could exhaust his slender reserve of fuel. Franklin drove into it at ten knots — and the anemometer on the bridge changed the quality of its metallic whine with a steady rise in pitch as its cups spun faster still.

At midnight the wind began to shift, and by dawn it was almost due west. Franklin’s motion eased a little, but Lahey felt no relief. The change in wind meant that his quarry was now driving out to sea at about four knots. Each hour that the westerly continued meant an hour added to the time it would require to bring the cripple back to port. And each hour of a tow in such a wind and sea meant three more tons of bunkers burned.

Lahey called the chief on the voice pipe. “Push her, b’y!” he shouted. “Give her steam!”

The shaft-revolution needle crept up slowly until Franklin was bulling her way at twelve knots. She came on like some antediluvian sea beast, half awash. The brief hours of daylight passed; the long winter night came down to the sustained roar of a full gale. Then as dawn approached on January 27, the wind suddenly began to haul into the north and to fall light.

Lahey was grateful for that, but he recognized it as a respite that must be of short duration. The glass had been falling steadily for fifteen hours, and it was now so low that a Magdalen Island seaman, coming onto the bridge to stand his trick, glanced at it and crossed himself. It was an involuntary gesture, and as he took the wheel the seaman had no conscious thought in mind except to hold the vessel on her course.

Lahey had many other thoughts. The radioman had been in constant contact with the Arosa for some time, and he reported that the casualty’s master believed her to have been drifting east at between four and five knots since noon of January 24. He had no position to offer, for it is impossible to obtain an accurate dead reckoning on a powerless ship which is moved only by the wind and seas, under a sky that hangs down to the mastheads. Nevertheless the radioman’s DF bearings indicated that the Arosa was at least a hundred miles farther eastward than she was thought to be. Lahey altered course a little.

Three hours before dawn Arosa’s signals were booming into the radioman’s ears. He passed a message to the skipper. Lahey rang down for half speed. Franklin nosed slowly through the darkness, her bow lifting and falling in a great uneasy arc like the head of a hound that sniffs the trail, then lifts again to catch a sight of the quarry through shortsighted eyes. At 6 A.M. the lookout on Franklin’s bridge bellowed his warning, and a faint gleam of lights came hard on the starboard bow.

There was only an uneasy breath of wind, but the tormented seas were so ugly that a master who risked his tug trying to make a connection in that heaving darkness might have been thought insane. Lahey was very sane. He knew with all the certainty of ten generations of sea dwellers that he had no other choice. He knew that the calm of the moment was the center of a great circular storm — a hurricane — and once the center had spun past there would be little hope of putting a line aboard the merchantman.

So Franklin came up in almost utter darkness, with only the pale beam of the little searchlight on her monkey island to give her sight. The seas were towering straight up, for they were masterless without the wind. The tug rose and descended with an abrupt and frightful motion. Nevertheless she still came in.

On the wing of the bridge, Franklin’s mate stood with his legs entwined around a stanchion, and with the rocket pistol in his hands. Above him the bulk of the Arosa towered and inclined like a falling mountainside. He pressed the trigger, and in the red glow of the rocket the line snaked from its pegs and vanished into darkness. By 6:30 A.M. Arosa was no longer drifting and alone in midAtlantic. The connection had been made.

The position of the two vessels was then eleven hundred and twenty miles east of Boston, six hundred and eighty from Louisburg, six hundred and fifty south of St. John’s, Newfoundland, and about eight hundred and forty miles east-southeast of Halifax. Franklin had sufficient bunkers left to allow her to steam about nine hundred miles under optimum conditions. Boston was impossible. The choice lay between Louisburg, Halifax, and St. John’s, but it depended almost entirely upon what happened when the eye of the storm had passed and the gales had begun anew. Once more Lahey drew on his intuitive knowledge of the Western Ocean. St. John’s was out; for the gales which would soon be upon him would almost certainly be strongest from the north and northwest quarters. Between Louisburg and Halifax there was but little choice, except that the Foundation Josephine was in Halifax and. though still under repair, might yet be able to assist the Franklin if need arose. Lahey gave his orders, and the wheel came over. The course was northwest by west — for Halifax.

The Arosa was a heavy ship, and in that gigantic and jumbled sea the strain upon the towing wire was excessive at a towing speed of three knots. Lahey did not dare exceed that speed. Progress was desperately slow, too slow. By 8 P.M. on January 27 the two ships had made good no more than fifty miles toward the west. And by that time the uneasy armistice had long since ended. The storm center had gone by shortly before dawn on the twenty-seventh, and by 9 P.M. the vessels were beset by a full hurricane blowing ninety miles an hour out of the northwest. The temperature, which had been steady at ten degrees of frost until noon, dropped down to zero. The old sea giants rose to the new impetus of wind and were cut off like grain in a wheat field, so that their white heads were driven level with the horizon, savagely striking Franklin’s upper works and freezing.

Nevertheless, and incredibly, Franklin was still making a passage west at the rate of half a knot. She held on to that half knot until midnight. And then the event that every man had known was coming happened. The wire parted. Because of her great bulk, Arosa began to blow off to the southeast at a speed which Franklin hardly dared to match under power, for fear she would be pooped. All the rest of the night the two vessels drove back out to sea. At 7 A.M., in the false dawn, Lahey came in to reconnect. The wire was made fast at the first attempt — for the Norwegians are great seamen, too — and the tow began anew.

The first fury of the gale was spent, and now the wind settled down to accomplish by attrition what it had been unable to do by direct assault. Blowing steadily out of the northwest at velocities between sixty and eighty miles an hour, it thundered with such incessant violence that the men aboard the Franklin could no longer hear it. Only a cessation of sound would have penetrated into their conscious minds; and there was no cessation. The old vessel herself was such a cacophony of complaint as she rolled and pitched and yawed that the men below could not have heard the gale if they had so desired. They clung to whatever handgrips they could find, and time went on.

They towed from 7 A.M. on January 28 until noon on January 30, and in that stretch of time they only succeeded in recovering the distance they had lost in seven hours on the night the wire parted.

THE log entries for those days are succinct, but their brevity was not due to a lack of appreciation of conditions or to the indifference that men display in the face of the inevitability of things over which they have no control. The log entries were brief because there was no more that could be said.

January 29. Towed twenty miles in past twenty hours. Whole gale from NW. Very heavy head seas. Low temperature continues. Ship icing heavily. Continuous snow blizzards.

January 30. Weather unchanged. Ship icing badly. At 2100 radio out of action due to loss of aerial from icing. Towed twenty miles in last twenty-four hours, Fuel will not last to Halifax.

Two days and nights . . . six lines of spidery handwriting on a long, ruled page that looks for all the world like a ledger sheet from a countinghouse. And that is all. Only in that one phrase, “Fuel will not last to Halifax,” is there any hint of an awareness not only that the battle might be lost, but that Franklin herself was desperately beset.

And she was so. Her radio was permanently out of action. It had proved impossible to keep the constantly making ice reduced to a safe margin, and the little tug was in danger of losing her stability — a matter of deadly concern considering the manner in which the seas were mauling her about. This danger increased hourly as the bunkers became lighter and as the load of ice on the decks and the superstructure became heavier. Nor was this all. The aged machinery, so superficially repaired a few weeks earlier, was, for the first time in Franklin’s history, displaying signs of serious fatigue. The engineers were never still. Nursing the auxiliaries and watching the main engine with eyes in which weariness had been banished by the anticipation of disaster, the engine-room crowd were living with an almost momentary expectation that finally the heart of the old ship would falter and would stop. There was more. The bilge pumps were working harder than they should have needed to. Franklin was making water.

During the morning of January 31, the wind rose to force 10 out of the northwest, and since it was then impossible to make a course for Halifax Lahey eased off to the westward.

He had barely swung his vessel off the wind when the gale veered into the northeast.

Arosa now refused to tow. She fell off until she was lying right out abeam of Franklin. The consequent strain on the towing gear soon became intolerable, and in desperation Fahey attempted to bring Franklin’s head up into the new gale so that he could at least hold Arosa steady, even while both vessels were being blown back out to sea.

For the first time in her life Franklin was slow to answer her helm. The loss of trim had brought her down by the head, and she came around sluggishly — too slowly — into the teeth of the new enemy. Rolling heavily as the seas struck full on her starboard bow, she lurched like a stricken thing — and then fell off. The tow wire rose almost clear of the seas. For an instant it held the strain, and then with a horrifying wrench the towing winch itself tore loose from its bed on Franklin’s afterdeck. Ripped deck plates curled like paper in a breeze. The drum tore from its socket, and half a mile of wire screamed out into the depths astern.

Completely out of control now, Franklin rolled down into a trough and was instantly swept from end to end. The sea poured in through the gaping wound where the winch had stood. The dynamos were inundated, and all electric power failed. Water rose above the bedplates and swirled about the auxiliaries. The engine slowed suddenly, and when it again picked up its beat there was a clatter in the main bearings that brought the heart of every man who heard it into his throat.

On the bridge Fahey had seized the wheel himself, and with his great hands and his indomitable will he strove to bring his vessel up out of the trough where she lay drowning.

THE officers on Arosa’s bridge had watched events with agonized emotions. Through a curtain of driven snow they had seen the wire go slack, had seen Franklin go over until her stacks were lying almost level with the sea, and had seen her swept so that she vanished from their sight in a towering column of grey spume.

They never saw her again. The wind screamed down to drive the scud into their eyes, and when it lifted briefly a few minutes later, the tug had vanished.

Arosa’s radio was still operational. Her new SOS was received in Halifax within the hour. It gave no details of what had happened, and the Foundation staff assumed that Franklin had only suffered minor damage but needed relief. It was not until several hours later, and until several messages had crossed the grey sea void between Arosa and the land, that fear began to grow. Then call after call began going out under Franklin’s code sign. There was no reply.

All that night the shipwrights and fitters worked on the Fosephine so that by morning of February 1 she was again ready for sea. As she left Halifax, that port was blanketed under a two-foot fall of snow. The northeast gale met her at the harbor entrance, and she was taking it green over her foredeck before she cleared the outer automatic buoy. But Fosephine was being driven. It was no longer entirely a matter of succoring a crippled merchantman; now there was the additional incentive that a sister tug was dying somewhere in that passionless expanse of broken sea.

Captain Cowley, on Fosephine’s high bridge, doubled the lookouts. His course was out along the track that Franklin might be following if she was still afloat. In the radio shack Fosephine’s operator never left his set, and at ten-minute intervals he tapped out Franklin’s call sign. There was no response. At noon on February 2 the master of Arosa, queried by Cowley, gave it as his opinion that the Franklin had gone down. Neither he nor his officers believed that she had been able to survive the blow that they had seen her take.

In Halifax the tension mounted. Nothing was known. Everything was feared.

Josephine came on with a disregard for the pounding she was taking that gave a lasting greatness to her, and to her master too. At 6 P.M. on February 3 she raised the grey hulk of the Arosa about one hundred miles east of the point where the Norwegian ship had parted from the Franklin. During a lull in the gale Cowley connected his towing wire, and with an inner reluctance that he did not show, he turned westward, Boston bound. The merchantman came first. Somewhere to the cast the Franklin might have been still alive, disabled, dying slowly — but he could not search for her. The merchantman came first.

Fosephine’s battle to bring the Arosa into Boston is an epic in itself. Some measure of the trials of that voyage can be taken from the fact that even Foundation Josephine could not hold fast to the Norwegian and on one occasion was parted from her for twenty-nine hours. It was not until February 11 that she was able to ease her battered charge into safe anchorage, bringing to an end the twenty-one-day ordeal of the Arosa.

The story of Foundation hranklin, however, ended in the wind-swept dawn of February 5. It ended when there came a message from the signal station at Chebucto Head — a message that brought Reginald Featherstone, the salvage master, out of his bed and sent him racing through icy streets toward the company wharf. In the first bleak light of day he stood with a dozen others on the Foundation dock and watched with unbelievingeyes the slow, infinitely painful progress of as strange a phantom as ever fumbled its way into Halifax harbor.

She came in under quarter power, which was all that she had left within her. She was so heavily encased in ice that she would not have been recognizable to any man who had not known her well. She was listing twelve degrees to port, and she was so far down by the head that those who watched her held their breaths for fear that she would plunge back into the hungry seas from which she appeared to have risen, wraithlike, in the winter dawn.

The watchers on the dock need have had no fear that she would fail to reach her old familiar berth. It was the grey seas under and the white winds above who had failed, in this their last attempt to take her to themselves.

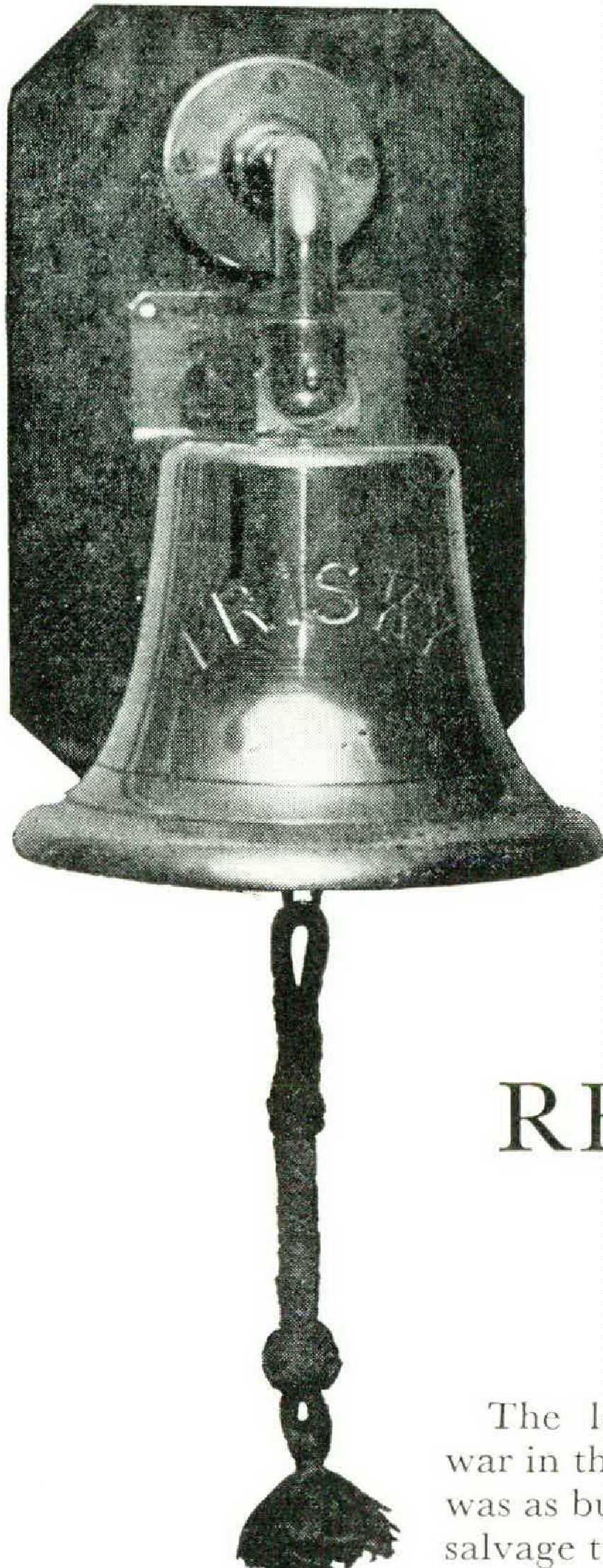

The Franklin had returned from her last voyage. She had come to the end of her days, and there remained only the inevitable dissolution under the hands of the ship breakers. Yet she did not pass entirely into oblivion, for they took her bell, the same one she had when she bore the name “Frisky” and lay in the graveyard in Hamburg harbor, and hung it in a room overlooking the berth which she once occupied.

It hangs there now. And on clear and sunny days the light streams in through the windows and kindles a yellow fire in the polished brass, so that the black inscription — FRISKY — incised deep into the metal, stands out with a bold clarity.

The bell sleeps silent in the warm sun, nor does it still ring the changes in the watches as it did through four decades, ft is somnolent on those fine days.

But there are other days — days when the Western Ocean takes up its ancient feud against all ships; when the storm scud drives low over a foam-flecked harbor; when the international distress frequency quickens to sudden life. And in those times the bell and the spirit of the gallant little ship whose voice it is awaken from their sleep.

The old bell sounds. Its voice rings sharp and urgent over the docks, and men pause in their occupations and turn toward the berth — once Franklin’s— where the latest of her inheritors lies ever ready. The bell sounds. Foundation Vigilant’s lines are slipped. She backs into the stream and swings her head toward the open sea, toward the storm-shrouded distances where a crippled vessel lies beset by the hungry ocean.

The eternal battle between the rescue ships and the grey seas begins anew — and it is Franklin’s voice that sounds the call to arms.