Inmates sent home during COVID-19 got jobs, started school. Now, they face possible return to prison

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In the weeks and months since he was sent home, RJ Edwards found a job, bought a car, got an apartment for him and his mother and started working toward a bachelor’s degree in computer science.

He works as an operation manager for a solar company in Tampa, Florida, while taking online classes at Hillsborough Community College. He wears an ankle monitor and calls his halfway house every day to report his whereabouts – part of the terms of his home confinement. Twice a week, he attends drug therapy sessions, a consequence from years of drug and alcohol abuse. He also paints, a skill learned after nearly a decade of imprisonment.

Nine months since leaving prison, Edwards faces the possibility of being forced to return – a devastating scenario for him and potentially thousands of others who spent the past year rebuilding their lives.

Edwards, 37, is among the more than 24,000 nonviolent federal prisoners who have been allowed to serve their sentences at home to slow the spread of COVID-19 inside prisons. But a Justice Department memo issued in the final days of the Trump administration says inmates whose sentences will extend beyond the pandemic must be brought back to prison.

Isolated and scared: The plight of juveniles locked up during the coronavirus pandemic

What about redemption, rehabilitation, recidivism?

Advocates urged the Justice Department to rescind the memo, which was issued by the agency's Office of Legal Counsel. They say it defeats the whole idea of rehabilitation and contradicts President Joe Biden's campaign promise to allow people with criminal pasts to redeem themselves.

"They let us go, and we reintegrate, and then it feels like nothing matters. All the hard work you put in, it doesn’t matter. We’re just a number to them," said Edwards, who has five years left to serve.

During a congressional hearing, Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, raised concerns about sending people back to prison, especially those who have been following the rules.

Of the 24,000 prisoners who were allowed to go home, 151 – less than 1% – have violated the terms of their home confinement and three have been arrested for new crimes.

"This highlights how effective home confinement can be," Grassley said.

Amid ramped up vaccination efforts, prison advocacy groups fear that inmates, many of whom have been out for a year, will soon be brought back to prison.

"These people are twisting in the wind, and they’re growing anxious every day," said Kevin Ring, president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums. "It’s not simply that (the Justice Department) should fix it. They should fix it yesterday."

"This doesn’t seem that difficult," said Ring, who himself served time in federal prison. "They know how to change Trump policies they don’t like, right away."

Reincarcerating people who, for the past year, have been law-abiding would disrupt their rehabilitation and would do little to improve public safety, according to a letter more than two dozen groups sent to Attorney General Merrick Garland last month.

"Establishing community ties and deepening family connections are known to be significant positive factors for reducing recidivism," according to the letter. "Disrupting that process would mean disrupting safe re-integration into society and damaging networks that are vital to improving public safety."

Keeping people behind bars is also costly.

In 2018, the annual cost of housing just one federal prisoner was about $37,000 or $102 per day.

‘There's no rush,’ Bureau of Prisons chief says

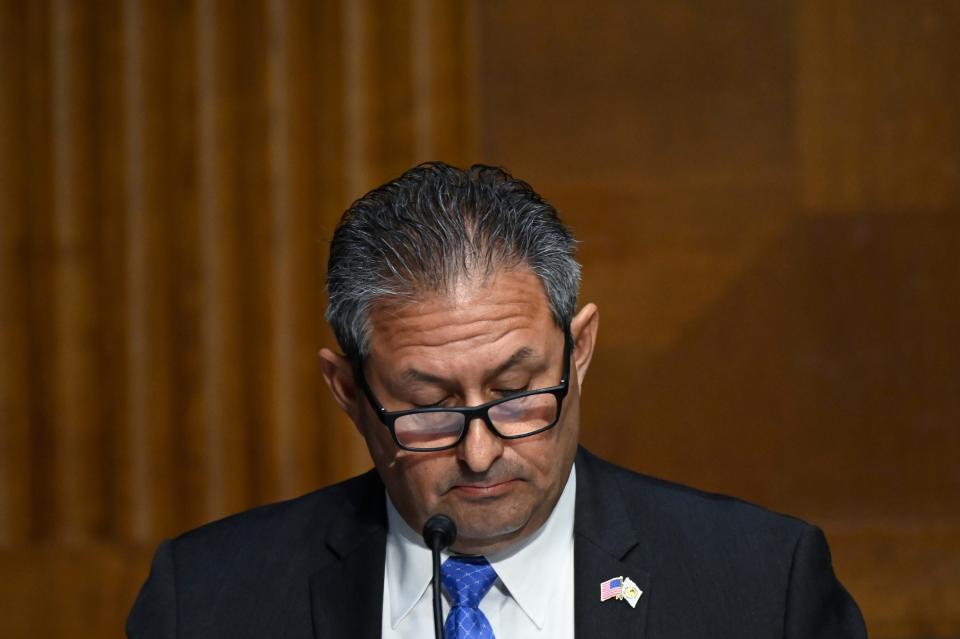

Federal Bureau of Prisons Director Michael Carvajal pushed back against criticisms that officials will disrupt people's lives.

"If they have successfully been out there, we're going to use good judgment and common sense and work within the law to make sure that we place them appropriately," Carvajal told lawmakers last month. "I don't want somebody to believe that the Bureau of Prisons somehow doesn't want to let people out. That's not accurate. We want to let them out within our authorities and within the law."

Officials said they don't believe the issue is urgent.

A statement provided by the Justice Department said the Bureau of Prisons can choose to keep inmates on home confinement if they’re near the end of their sentences. For inmates with years left to serve, the prospect of going back to prison is not imminent because Biden extended the COVID-19 national emergency declaration, and the public health crisis is expected to last for the rest of the year, the department said.

"There’s no rush" to bring prisoners back, Carvajal told lawmakers.

Who gets to serve at home?

Federal law allows inmates to serve either the remaining 10% or six months of their sentence, whichever is shorter, through home confinement.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, signed last year by President Donald Trump in response to the pandemic, allowed prison officials to send home thousands of nonviolent and elderly inmates who had not met these criteria. Among those released were former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort, who has since been pardoned, and Trump's former personal attorney Michael Cohen.

According to the Justice Department memo, the coronavirus relief act was not intended to allow inmates to stay on home confinement after the pandemic, and the Bureau of Prisons must be prepared to potentially take "a significant number" of prisoners back to its facilities.

It's unclear exactly how many inmates will have to go back to prison once the pandemic is over.

In the past year since they were sent home, the majority of these inmates have finished their sentences or have met the criteria to stay on home confinement.

As of mid-April, 4,500 inmates on home confinement would not have qualified if not for the pandemic, although many of them are likely to meet the criteria in the next months. About 2,400 have more than a year left in their sentence, Carvajal told lawmakers.

A little more than 300 have five years left to serve.

That includes Edwards, who was sentenced to 17 years for wire fraud.

He was sent home in July. By August, he found a job.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

If he's sent back to prison, his mother, who sometimes needs help getting out of bed in the morning, will be by herself, Edwards said. His brother can help, but he does not live in the area.

Edwards said he found out about the memo Jan. 28, his birthday, two weeks after it was issued.

"I remember the feeling, just the pain, the shock. It’s really been hard ever since, living every day thinking about that. It’s always on my mind," he said. "It just feels like there’s a black hole and nothing’s happening. It’s scary."

Reincarceration could 'shut down' progress

Gwen Levi said sending her back would not only put her at risk of getting COVID-19; it's also costly and impractical. The 75-year-old, who has four years left to serve, has degenerative joint disease, hypertension, cataracts and is in remission from lung cancer.

Levi was serving more than 30 years for drug conspiracy charges. It was reduced to 24 years as part of the First Step Act, a Trump-era criminal justice bill that shortened sentences for nonviolent drug crimes.

Last summer, Levi left prison, believing it was for good.

She has since immersed herself in volunteer work for criminal justice groups in Baltimore. One of her sons started plans for a family business, she said.

"Returning me back would shut down all the progress that I am making," she said. "We're beginning to think about things for the future. To have to go back to the past would be devastating."

COVID-19 in prisons: Feds to expand home confinement for elderly inmates to avoid larger coronavirus outbreak

‘Harder for the family’

Like Edwards, Jesse Rodriguez was sent home last summer and found a job. He's a certified technician for a heating and air conditioning company in Odessa, Texas, and attending online classes at Odessa College.

He, too, thought he would spend the rest of his sentence outside prison. Rodriguez, 45, has four years left in his 15-year sentence for drug charges.

"You let us out for a reason, because we weren't a threat to society. You let us join back with our families. I mean, it's harder for the family than it is for us," Rodriguez said. "Your family, they miss you when you're gone."

Rodriguez has four children: two daughters in their 20s and two sons, ages 12 and 13. Sending him back to prison would jeopardize about $600 in child support payments he makes every month for his boys, he said. Rodriguez fears losing their father again would lead them down the wrong path.

"It's important that I stay in their lives," he said.

For Edwards, going back to prison means all his hard work this past year would've been a waste.

"If I knew I was going back," he said, "I wouldn’t have made all the choices I made."

He wouldn’t have bought a car or rented a bigger apartment that his mother wouldn't be able afford by herself with her Social Security income.

He wouldn’t have started college.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Trump memo says inmates sent home due to COVID must return to prison