Laid out under the ornate vaulted dome of the Grand Palais, Paris Photo is a daunting prospect even for the seasoned photography buff. It is, first and foremost, a market: the increasingly well-heeled clientele who are drawn there reflect the commercial clout of photography’s equivalent of Frieze – with all the same tensions between art and the hard sell that entails. Your best bet is to ignore the sales pitches and wander through the vast network of exhibition booths at will, following your instinct.

On the contemporary front, I was taken with Eamonn Doyle’s big, vivid prints from his new series, K, which were on show at Michael Hoppen’s exhibition space. The series features a ghostly female figure, draped in all-concealing fabric and silhouetted in stark relief against the elemental landscapes of the Atlantic west of Ireland. The images are a dramatic contrast to traditional renderings of grieving and hauntedness and to Doyle’s previous series of works, which depict the passing parade of people he encountered on the streets of his inner-city Dublin neighbourhood.

His photobook of the same name, also launched at Paris Photo, is a more personally rooted exploration of grief that includes multilayered handwritten letters from Doyle’s mother to his brother, Ciaran, who died aged 33, in 1999. The book comes with a 10in vinyl record on which musician David Donohoe has created a contemporary rendering of a traditional Irish keening lament. Doyle continues to surprise with his ambitious multimedia approach.

On the lookout for newer talent, I was drawn by Senta Simond’s almost modernist black and white portraits of her friends. The young Swiss photographer is having a moment following acclaim for her first photobook, Rayon Vert, and a solo show at Foam Amsterdam. Influenced by the French new wave director, Eric Rohmer, her arrestingly composed portraits have a palpable intimacy, as faces appear in closeup or through a blur of limbs. Despite the few prints on display, an easeful, almost sensual, atmosphere prevails.

Also at Danziger, the young Irish photographer Jean Curran was showing two prints from her intriguing series, The Vertigo Project. With the permission of the Alfred Hitchcock estate, Curran has selected 20 frames from the hundreds of thousands that make up a rare original Technicolor print of Hitchcock’s 1958 masterpiece. She has created her prints using the same dye transfer process by which the movie was made. The results highlight the compositional skill that underpinned the original film, but also stand up in their own right as luminous still images, unmoored from their Hitchcockian narrative, but retaining the heightened, ominous undertow that defined the master’s most surreal film.

Just as strange, but in an altogether different way, are Kensuke Koike’s deconstructed passport portraits, which were on show at Approche, a space on Rue de Richelieu devoted to young conceptual photographers. In a collaboration with vernacular archivist, Thomas Sauvin, Koike has sliced and reassembled prints taken from a handmade album of original portraits created by a Shanghai University photography student in the 1980s as part of a course on how to make the perfect passport photograph. Eschewing digital manipulation, Koike creates surreal collaged faces by punching holes in portraits or slicing them into strips or circles. Nothing extraneous is added, just pieces from the original prints. The results are startling in their precision and intricate invention.

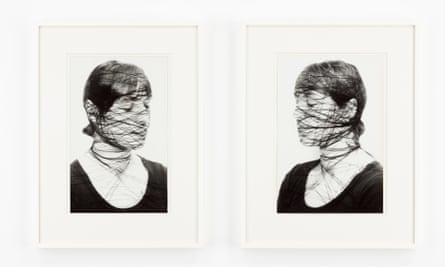

At Richard Saltoun’s space in Grand Palais, an older generation of boundary-pushing female artists was on show, including work by Renate Bertlmann, Penny Slinger and Annegret Soltau, all of whom merged photography and performance. It was Soltau’s work that mesmerised, with portraits of her face wrapped in black thread, the placid nature of her gaze lending the already striking images a surreal undertow. Made in 1975-76, the black and white images reflect the more subtle side of an artist whose later stitched portraits are a more visceral exploration of female identity and psychology.

It was wonderful, too, to see a grid of Peter Hujar’s figures and landscapes. His pared-down black and white studies, whether of sea waves or bodies bent into strange shapes evince a singular style rooted in a rare kind of fragile stillness. Until his death in 1987, Hujar was a well-kept secret on the downtown New York arts scene, but his reappraisal continues and, as this well of images shows, his work can instil calm even amid the crowded environs of a commercial art fair.

The Paris Photo/Aperture photobook of the year award went to Laia Abril for her deeply researched, conceptually thought-provoking, A History of Misogyny, Chapter One: On Abortion (Dew Lewis). It’s been quite a week for Abril who, a few days previously, was shortlisted for the Deutsche Borse photography prize. Her book – and the attendant exhibitions – are important documents for our time, and it’s good to see politically driven work being acknowledged at a time when too much process-led contemporary photography seems wilfully disengaged from the tumultuous events we are living through.

Alongside Koike’s work, my highlight of the weekend was a visit to La Cite gallery in the ninth arrondissement, where there was mischievous invention aplenty from the maverick mind of Thomas Mailaender, contemporary photography’s reigning master of the absurd and the appropriated. The Fun Archeology houses just a sample of his vast stock of source material, the mainly internet-found oddities that provide the raw material for his photobooks and exhibitions. It is by turns alarming and hilarious. Where else could you find a “real” photo of Bigfoot, a fan album in which images of Grace Kelly have been doctored with Tippex-ed tears, a selection of porn postage stamps – as ingeniously tasteless as their name suggests – and an elaborate leather jewellery box containing a stick-on velcro Hitler moustache. Not, then, for the easily-offended, but, if you’re in Paris before 24 November, I’d recommend it – you won’t be as appalled, enthralled and entertained by any other exhibition this year.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion