When you think of the most dangerous jobs in the U.S., you might imagine something like logging, fishing or truck driving. But in 2020 one of the deadliest professions of all did not involve operating heavy machinery, braving the elements or driving big rigs—but rather caring for the elderly.

As COVID-19 swept across the world last year, death rates among nursing home staff ranked among the highest for any job in the U.S., based on a Scientific American analysis of data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Bureau of Labor Statistics. But the CMS, which sets quality standards for skilled nursing facilities, only started requiring nursing homes to report such deaths in May 2020—just after last spring’s devastating peak in COVID deaths in parts of the country. So the calculated death rate is almost certainly an undercount, says Judith Chevalier, a Yale University professor of finance and economics who helped analyze the data.

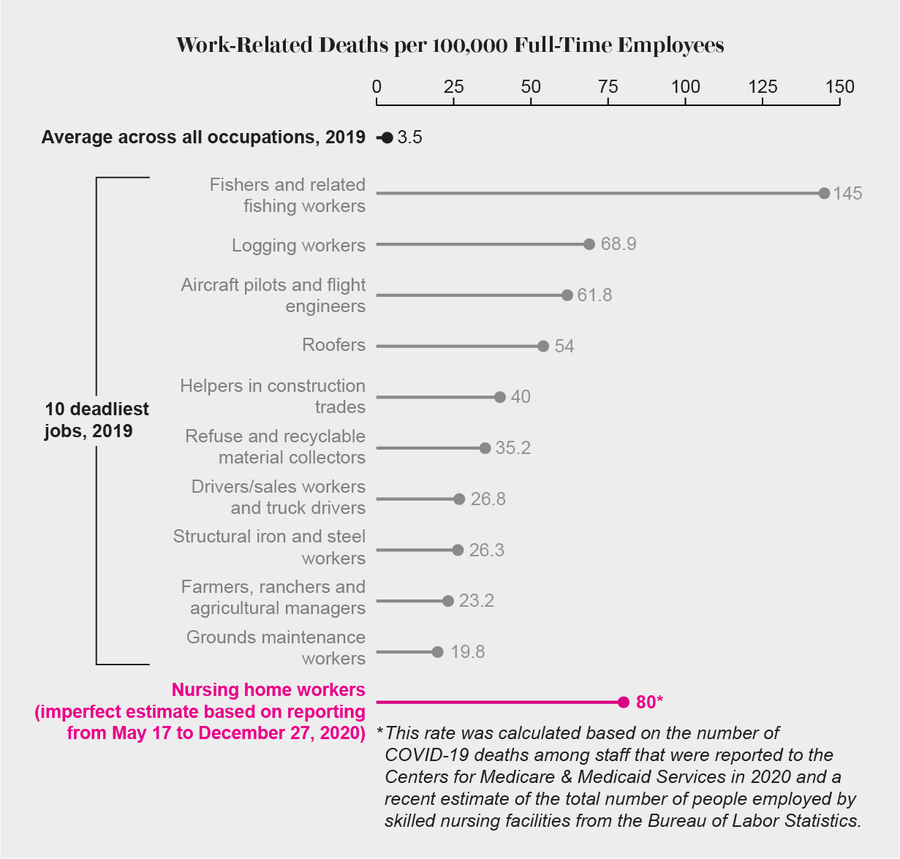

The pandemic’s high toll among nursing home residents is well known, but the impact on staff has been far less visible. Workers in skilled nursing facilities had at least 80 deaths per 100,000 full-time employees last year. This estimate was calculated by dividing the total deaths among nursing home staff reported to the CMS from May 17 through December 27, 2020, by the total number of people who work at such facilities, as reported by the BLS. In comparison, fishers and related workers had 145 deaths per 100,000 people in 2019, according to data from the BLS. Loggers had 68.9 deaths per 100,000 people in the same year. Given that the CMS data for 2020 were only reported from last May onward, the full year’s actual death rate for nursing home staff may have approached or even exceeded that of fishers.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics (2019 jobs data and total nursing home workers estimate); Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (nursing home worker deaths)

Exact comparisons are challenging because CMS data on nursing home worker deaths come from a patchwork of reporting standards that vary by state and facility. Chevalier says the agency did not make it clear whether nursing facilities should report cumulative deaths at the time they started collecting the data in mid-May or should start counting from that point. And it is also hard to match statistics from individual nursing homes to state-level data because facilities may have started reporting them at different times. “It’s a mess,” Chevalier says. Furthermore, the CMS data only include people who worked in certified skilled nursing homes, not those in the many other types of assisted living facilities, she notes.

A CMS spokesperson says patient safety, access to care and data transparency are priorities for the agency. Some nursing facilities may have struggled to submit their information to the reporting program when it started last May, so parts of the early data may be inaccurate, the spokesperson notes. In addition, some facilities may have chosen to report cumulative data going back to January 2020. Doing so could have led to higher case or death numbers, compared with those of facilities that just reported the data from last May onward, adds the spokesperson, who asked to be quoted on background.

Inside nursing homes, certified nursing assistants, or CNAs, perform some of the most important—and often thankless—work. It can include feeding nursing home residents, bathing them and turning them over so they do not get bedsores. Yet many of these workers are paid minimum wage and often have little or no sick leave, says Lori Porter, co-founder and chief executive officer of the National Association of Health Care Assistants, an organization that represents CNAs. Additionally, nursing homes were chronically understaffed and underfunded even before the pandemic. So when COVID hit, many of them were vastly unprepared. They lacked personal protective equipment (PPE), adequate infectious disease training, access to frequent testing and backup staff to cover for sick employees. As a result, these facilities have been among the communities hit hardest by the pandemic.

“If COVID has had a positive [effect] on anything, it’s that it’s no longer nursing homes’ dirty little secret—it’s America’s—that we don’t take care of our old people,” Porter says. “That’s the real story.... Why are we warehousing our old people in human filing cabinets?”

Last summer Porter, a former CNA herself, served on the Coronavirus Commission on Safety and Quality in Nursing Homes, which the CMS tasked with assessing such facilities’ response to the pandemic. And last July she co-authored an op-ed in the Washington Post about the dangers of being a nursing home worker during COVID. “We know the compensation is way too low, but no one successfully addressed that,” she says. “Along came the pandemic, and we had way too few [people] to take [it on]. There’s been a lot of fear, a lot of death all around.”

There are numerous possible reasons nursing home workers have been dying of COVID at such high rates. For example, many facilities lacked protective equipment such as high-quality face masks, face shields and gowns—especially during the pandemic’s early months. And the nature of nursing home care involves prolonged close contact with residents, making it nearly impossible to socially distance.

Nursing homes could not do all the COVID testing they wanted to early in the pandemic, Chevalier says. Such testing would have been critical for identifying staff with asymptomatic or presymptomatic infections. And even if employees were able to get a test, and it was positive, many of them probably declined to stay home because they lacked sick leave and could not afford to forego their income, Porter says. CNAs make a median wage of about $14 per hour. In a 40-hour workweek, that wage amounts to less than the $600 per week in extra unemployment benefits many people received last summer, Porter and her colleagues note.

On top of that, many nursing homes were already severely understaffed before the pandemic, so there were too few people to fill in when some fell sick. Some nursing staff and contractors work at multiple nursing homes and may carry the virus around, research by Chevalier and others has found. And some nursing home workers’ low income prevents them from seeking adequate care for themselves. They may also have preexisting conditions that put them at risk for developing severe COVID.

“Long-term caregivers are risking their own safety by coming to work every day to care for those most vulnerable to this virus. They are our forgotten health care heroes and are committed to providing the highest quality care, even in the midst of a pandemic,” says a spokesperson for the American Health Care Association, a nonprofit organization that represents nursing homes and other assisted living facilities. The AHCA notes that research suggests outbreaks in nursing homes were correlated with spread in the surrounding community. “Even the best nursing homes with the most rigorous infection control practices could not stop this highly contagious and invisible virus,” the spokesperson says.

David Grabowski, a professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, who co-authored the Washington Post op-ed with Porter, says he is “not at all surprised” at the high death rate among nursing home staff.* “Society never really invested in these workers,” he says. They are predominantly women, people of color and immigrants, he notes, and “we’ve exploited that workforce for a long time.”

Grabowski hopes one lesson society will take from this pandemic is that the long-term care system in the U.S. is broken. To fix it, he says, nursing homes must be able to hire and retain the staff they require and adequately pay them. There is also a need for better infection control measures, which would help against not just COVID but flu outbreaks as well. Better data collection would additionally aid in ensuring transparency and accountability. Ultimately, all these things require more money than current Medicaid rates can provide, Grabowski says. Nursing homes also need better federal regulation to ensure that they are providing adequate care—but that requires investing in them, Porter points out.

Although PPE and testing have become somewhat more available, nursing homes are still a dangerous place to work. COVID vaccines are now being rolled out to these facilities, but there is significant vaccine hesitancy among nursing home staff. A big part of that reluctance stems from a lack of trust in a government they feel has neglected them, Porter says. She recently resubmitted a proposal to the CMS for funding to establish a national CNA COVID-19 education portal—developed by her organization and designed specifically for nursing assistants—which would include information about the importance of getting vaccinated. Porter thinks having this guidance come directly from a group dedicated to CNAs would be more effective than having it come from the government. She says the message she wants to send to all CNAs is “We hear you. You are important. We’re protecting you.”

*Editor’s Note (2/18/21): This article has been updated to correct an error. The Washington Post op-ed was co-authored by Lori Porter, not Judith Chevalier.

Read more about the coronavirus outbreak from Scientific American here. And read coverage from our international network of magazines here.