How William Morris cultivated an artistic nature

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In his 1879 lecture, “Making the Best of It”, William Morris lays down his thinking on gardens, or how best to organise one’s “smoke-drenched scrap of ground among the bricks”. Fencing, he believes, should be orderly and flowerbeds full of things that are free and interesting, leaving nature “to do the desired complexity”. He admires China asters with their yellow centre and the snowdrop as a “wonder of beauty”. Scarlet geraniums and yellow calceolaria, however, are scarcely tolerable. Tropical plants, which nature “meant to be grotesque”, are best admired in a botanical garden. Morris had a dim view of hart’s tongue. “Don’t have ferns in your garden,” he writes.

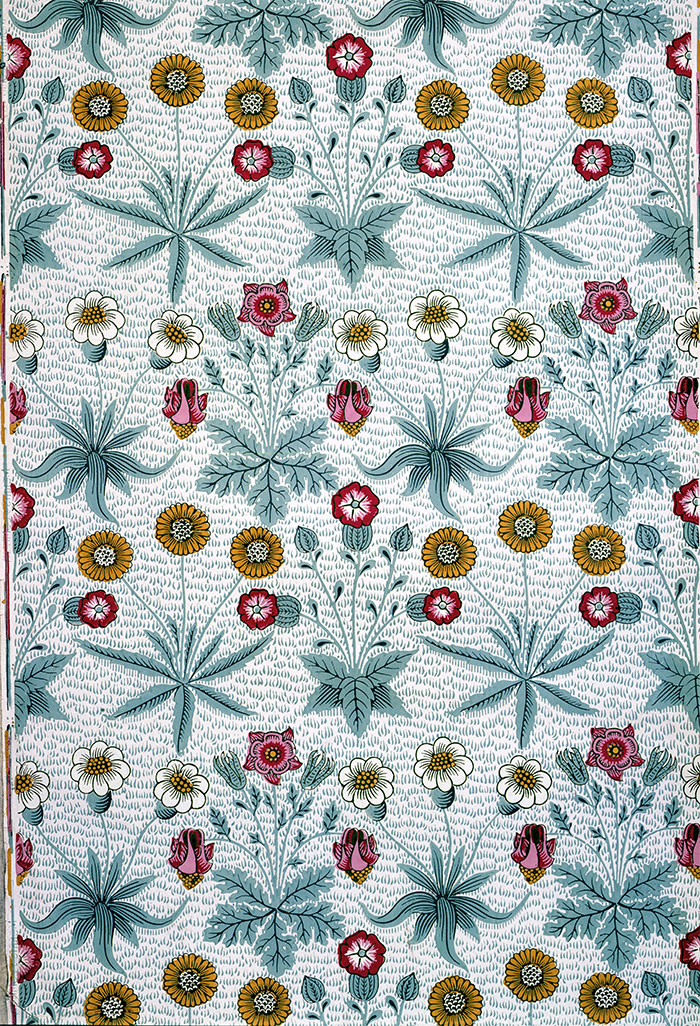

It is of little surprise that one of the founders of the Arts & Crafts movement thought seriously about gardens. The natural world informs almost all of Morris’s designs, not least his 50 or so wallpapers which depict stylised evocations of chiefly British wildness: acorns, blackthorn and tulips. While Morris’s own gardens inspired much of his work, and that of his contemporaries Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, his unconventional ideas about gardening influenced a generation of Arts & Crafts horticulturists, including William Robinson and Gertrude Jekyll. These themes are explored in two London exhibitions, The Enchanted Garden at the William Morris Gallery and Edward Burne-Jones at Tate Britain.

Morris’s affinity with nature began early. Growing up in Walthamstow on the outskirts of London, he spent a lot of time rambling around Epping Forest and the river Lea. “We know he took great delight in the countryside and in nature, and that continues and comes out in different ways, early on in his poetry and then later through his designs,” says Rowan Bain, senior curator at the William Morris Gallery, which occupies Morris’s childhood home. “He had a great sensitivity to the natural world through colour and shape.”

When Morris was in his early twenties, he took a trip down the river Seine with his friend Philip Webb, a trainee architect. Inspired by French medieval Gothicism, Morris commissioned Webb to build him a house in the Kent countryside with steeply pitched roofs, bull’s-eye windows and crenellations carved into the staircase. Completed in 1860, Red House — now a National Trust property in Bexleyheath — was not just a home for Morris, his wife Jane and their two daughters, but an artistic retreat from industrial London. “When they came here and their friends came here they would discard the dresses of the day and wear loose-fitting, medieval-inspired gowns,” says Elly Bagnall, house steward. “They wouldn’t have their hair up. No bodices here.”

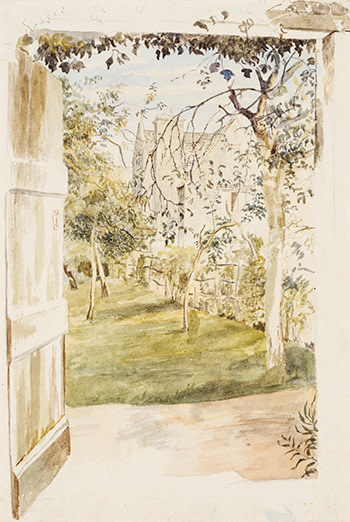

Red House was where Morris tried out different designs and techniques, some of which would be refined and put into production through his furniture and decorative arts company, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co (later Morris & Co). In the designs for the garden, as for the house, he broke with tradition. Victorian gardens were to be admired politely, from under parasols. On plans for Red House, now at the Victoria and Albert Museum, Webb writes: “clothe it with green”. (Visitors today must use their imaginations, as little remains of the gardens as they were in Morris’s time.)

Morris’s radical idea about gardens was that they should be an extension of the house. The plans show that the grounds were divided into “garden rooms” — defined spaces for particular use, enclosed by wattle fencing. He also instructed Webb to save as many of the Kentish apple trees as possible (a single tree from Morris’s time remains: a gnarled specimen that produces, in a good year, one-and-a-half apples). Planting was nativistic. In fashionable Victorian gardens, exotic species from distant lands were the flowers of choice. Morris planted dog roses. “I think it was about the honesty of it for him,” says Bagnall.

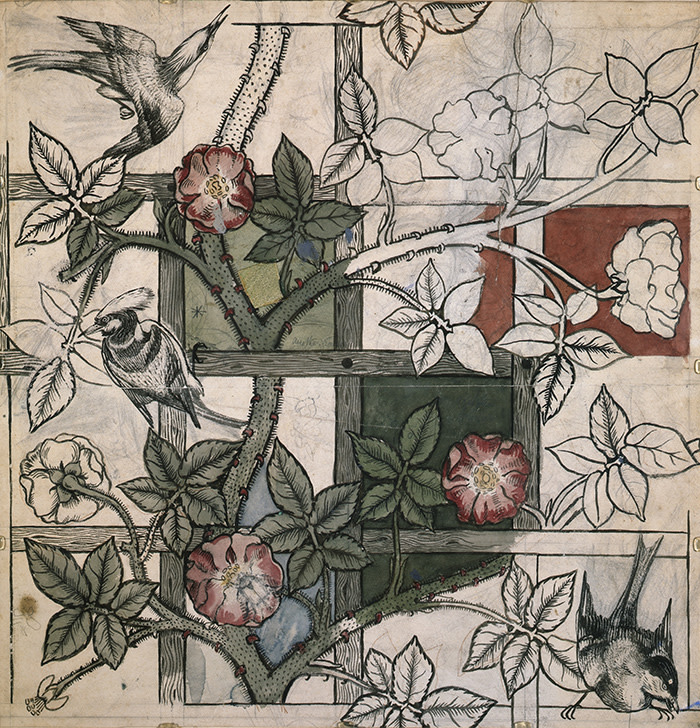

Morris’s studio overlooked the gardens and their influence is plain in his first wallpaper design. “Trellis” (1862) depicts a rose bush in bloom snaking in and out of a wooden trellis. The original design in pen, ink and watercolour stencilled in black reverse, is on display at the William Morris Gallery. The taste at the time was for wallpaper that was “very French, very frilly”, says Bagnall. “Trellis”, while patterned, is a more natural representation. “It’s not straight lines, not confined into spaces as it was previously. This is evident in his patterns and also the way that he gardens. He doesn’t want strict borders of parterres.” Similarly, the two other wallpapers that Morris designed at Red House, “Daisy” (1864) and “Fruit” (1865), demonstrate an informal naturalism. These papers, which were printed using hand-cut woodblocks loaded with natural dyes, did not sell well at first, but they are still in production today.

The gardens first at Red House and later at Kelmscott Manor in Oxfordshire, which Morris bought in 1871, became a reference for his wider artistic circle. Though the Arts & Crafts movement evolved in the city, underpinning the philosophy was a longing for the countryside and supposed “simple life” of the Middle Ages. This nostalgia is present in “Love” (1880s), Burne-Jones’s design for an embroidered panel that he worked into a watercolour, depicting a winged angel flanked by women and children in a meadow. The model for “Love” was Frances Graham, whom Burne-Jones adored. When she announced her marriage to another man in 1833, he added scarlet and purple anemones, symbols of rejected love and death.

By the 1870s, Morris was a popular decorator among the upper classes, leading to his comment that he was “ministering to the swinish luxuries of the rich”. A typical commission from this period, “The Pilgrim and the Heart of the Rose”, an embroidery of linen, coloured wool, silk and gold thread, is based on drawings by Burne-Jones; his paintings in the same series are on display at Tate Britain. One of a frieze of five parts commissioned by Sir Isaac Lowthian Bell for his dining room in Rounton Grange in Yorkshire, it depicts the story of Chaucer’s The Romaunt of the Rose, in which a pilgrim struggles through the brambles (symbolising temptation) to reach his desire, the rose bush, representing elusive love.

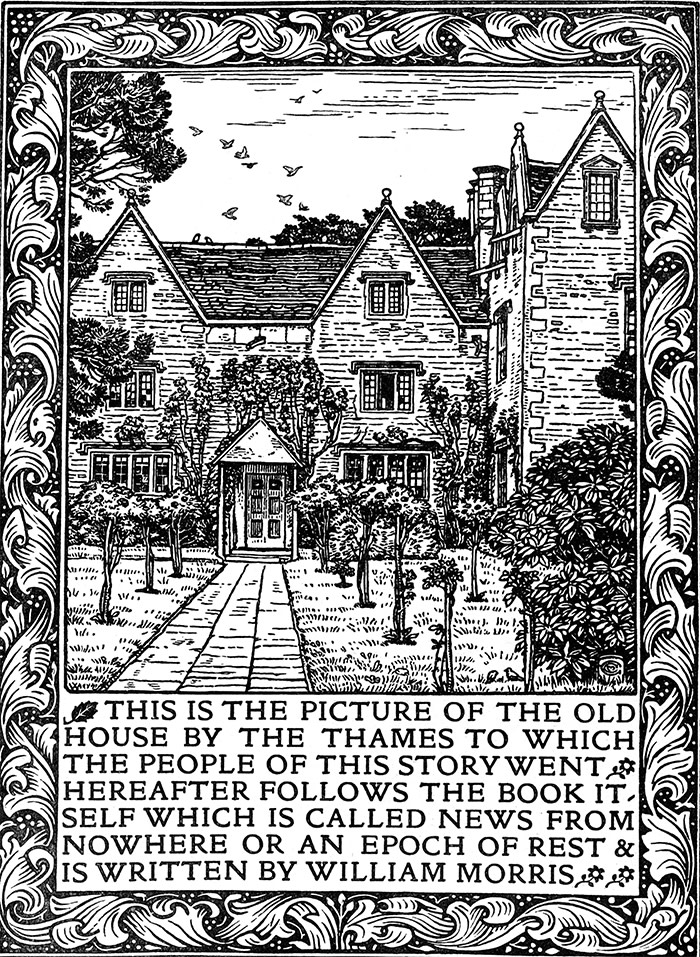

Morris thought the rose was the “queen” of flowers and planted them in abundance. In the mid-1990s, when the gardens at Kelmscott were restored, rose bushes were planted to flank the path leading to the front door. It mimicked the arrangement depicted in a woodcut frontispiece that decorates the original edition of Morris’s 1890 novel News from Nowhere. During the restoration, flowers and shrubs that either feature in Morris’s designs or are mentioned in his letters were planted: crocuses, aconites, primroses, hollyhocks and tulips. The idea was to create a style that echoes his aesthetic: deeply incised foliage, abundant fruits and large flowers. Part of a £4.3m lottery grant recently awarded to Kelmscott will be spent further renovating the grounds.

In Kelmscott, Morris found his ideal private pleasure garden. Enclosed by walls and divided by hedges, it was “both orderly and rich” and “fenced from the outside world”. By the time he wrote these lines in “Making the Best of It”, he had lived there for nearly a decade and it was at this juncture that he felt compelled to set out “something like a set of rules or maxims”. Though prescriptive and exacting, his writing is driven by an earnest desire to improve people’s lives the best way he knew how: “We want to make [people] think about their homes, to take the trouble to turn them into dwellings fit for people free in mind and body — much might come of that I think.”

Red House is open Friday, Saturday and Sunday until mid-December. Kelmscott Manor is closed for the winter season but reopens in spring

‘The Enchanted Garden’, William Morris Gallery until January 27, wmgallery.org.uk; ‘Edward Burne-Jones’, Tate Britain until February 24, tate.org.uk

Follow @FTProperty on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments