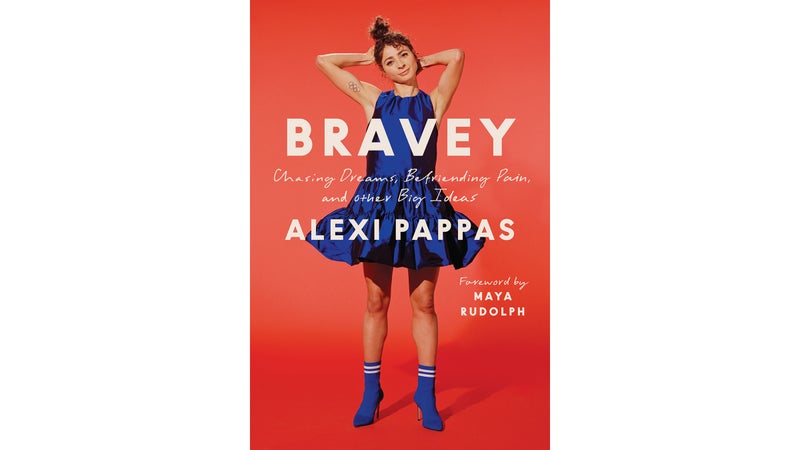

You’ve probably heard that Alexi Pappas isn’t an ordinary professional runner. In addition to being an Olympian in the 10,000-meters, the 30-year-old has also co-written and starred in multiple feature films. She often addresses her legions of young fans—whom she lovingly calls “braveys”—with short poems on her Instagram feed. (She studied poetry while in college at Dartmouth.) Her latest creative project is a memoir, Bravey, out January 12.

In many ways, the book represents a shift in tone from much of her earlier public presence. It opens with memories of her mother, who died by suicide when Pappas was four years old. Pappas’ own struggle with severe depression, which reared its head after the 2016 Olympics, is a major subject of the book. But there are also lighter themes that will be familiar to Pappas’ fans and followers: the importance of mentorship, self-belief, and chasing ambitious dreams.

I spoke with Pappas about the book, her decision to share her experiences with mental illness, and balancing creative work with intense training.

OUTSIDE: Can you start out by giving me the elevator pitch for your book and what it’s about?

PAPPAS: It’s a memoir in essays, with a foreword by Maya Rudolph. The trajectory of the book is an emotional arc: my editors and I decided to structure it so that it followed growing up with me and learning, after some early challenging memories—like losing my mom to suicide—how to find female mentorship and how to manifest the greatest version of myself in unexpected circumstances. And then it comes full circle, which wasn’t something we’d planned when we wrote the proposal because I hadn’t yet gone all the way through my own depression, but I realized it in the writing process.

Who do you consider to be the audience for this book? You have a huge fan base of younger runners, and you often address them in your social feeds. But there’s also some heavy stuff in here!

It’s not a children’s book, I think it’s for adults. And I consider a 14- or 15-year-old, especially in this day and age, mature enough to handle that kind of content. But I think the book is as much for parents as it is for dream-chasers, because so much of it is talking about my dad and how he raised us.

I didn’t write it just to speak to my immediate audience. I wrote it to do justice to my experience. On social media, I’m a lot more likely to post the thought at the end of the experience, which might come out in a whimsical poem. But a lot of those poems, people will now understand, have a lot of melancholy behind them and a real challenging experience that birthed that thought. That’s why I thought the book was an important medium—because on social media, it can feel like it doesn’t have the density behind it that it does. I think people can handle that at a young age. But part of it, also, is that some people think there’s a certain age where we outgrow seeking mentorship. And if you believe that, then maybe you do outgrow being an audience member for this book. But I would argue that you never need to outgrow seeking mentorship, looking up to people, and evolving. And so in that way, I think anyone who’s open-minded enough to have a mentor would be a great audience for this book.

As you said, one of the major themes in the book is about seeking out mentorship in your own career, and I was wondering if you see yourself as a mentor to those younger runners who follow you on social media, or if you think that’s a different kind of relationship?

Yeah. I think this is a full-circle awareness that if this kind of book existed when I was their age, I would have latched onto it. And so I always recognize on social media that anything I say, I need to feel comfortable with someone imitating, or absorbing, and interpreting for themselves. In writing this book, I tried to be careful with my words and be as honest and specific as possible, because I think that was where I could do the most good and also write with the most integrity. The more specific we are, the better, I think. It’s just sometimes a little bit gritty because the truth is maybe not what people thought.

You recently published a video with The New York Times about your experience with depression, and you write about that experience a lot in Bravey. Did you set out to have mental health be a significant theme in this book, and was it difficult for you to discuss that publicly?

When I was writing the proposal for the book with my literary agent, I was in the middle of the depression, and I didn’t have the understanding I have now that it would have been an OK thing to admit. I thought it was not OK and that it would ruin my chances of writing a book. And so it wasn’t in the proposal. What was in the proposal was my experience with my mom and how that shaped my outlook on life. But I hadn’t had the final third of the book, emotionally. I hadn’t realized that myself yet. And so when I set out to write the book, it would have been two-thirds of what it is.

When I started writing it, because it was essays, that allowed me to submit a few essays to my editors and we didn’t know how they’d ultimately fit in. One of the essays I wrote was the depression essay, and they weren’t expecting it. They learned about it for the first time when I sent them that chapter. And then I think we started to realize, “Oh, this is the book.” Because there was this evolving relationship with my mom even after she died, and then the mental health journey, that went hand in hand. It came about in the writing process because I was understanding that about myself.

What has the response been like to you sharing The New York Times piece and the parts of the book that are specifically about depression and mental health?

I think it hopefully pushed the conversation beyond, “This exists,” because there’s been a lot of conversation in the last few years that’s like, “Hey, elite athletes have mental health issues too.” But there’s been so little conversation about what to do about it. And what I’ve found, in the way people talked about my mom and the way that sometimes I hear people talk about someone else who took their own life, it’s as if it’s inevitable or they had to do it. And that’s how I grew up thinking about my mom because that’s what I was told. And really it irked me to my core because one, it was really sad. And two, it made me feel like if I ever felt that way, is it going to happen to me? Then do I just have to die? What I hope this has done is pushed the conversation beyond acceptance to a point where we can see mental illness as a solvable “injury,” and that there’s a path forward.

And also, not blame the dreams themselves. I think sometimes people are like, “Oh, it’s the Olympics, too much pressure,” or whatever other dream people have, like going to a certain college or something. And actually, the Olympics and these other dreams are wonderful experiences. And we should be prepared far before that. I wish I was prepared as a teenager to understand this so that I could have done the prehab, if you will, if you consider the body metaphor.

One of the other things I found refreshing in your book is that you’re so open about things like partying in college, since a lot of professional runners can be a little one-dimensional in their public presence. Were you hoping to communicate anything specific by including those kinds of details?

Just the truth. And with social media, I just did not find that Instagram was the place to put out my diary entries. It was too fragmented to share with people that becoming the person I am today—who maybe some people are looking up to—was a roller coaster, labyrinthian process. I’ve always tried to do my best in the moment that I was in, and there were times in my life when I didn’t think that it would be useful to not go out and socialize. If I hadn’t gone out to parties, I wouldn't have met the love of my life, because I met him at a party. And he wasn’t a runner, so I wasn’t going to meet him in those contexts. So that makes it tangibly worth it.

But also, I wanted to give young Braveys and their parents, who might read this, the understanding that who we are in a moment doesn’t represent the whole journey. And to suppose that someone is exactly as they were today when they were 12 or 15 or 18 is probably not true. And I feel a responsibility to share. It would be sad to me if someone suppressed some experiences, whether they choose to do it at a party or choose to do dance for a while and then find running or whatever. They need to be manifesting the greatest version of themselves at any one moment, and that might look different when you’re 18 than when you’re 25.

One of the other messages in your book is about the commitment it takes to achieve ambitious goals. One thing that stood out to me in the chapter toward the end about this (“For Those Who Dream”) was that there wasn’t much discussion of the bigger, more structural barriers that might prevent someone from achieving an ambitious goal even if they’re very committed to it. Have you gotten that critique before, and how would you respond to it?

I was in some of the final editing this past summer and I did write a line in there that talks about systemic barriers. But it's not what my book is about and I think my personal barriers were the ones I wrote about. I tried to speak to my experience, but in the edit, I remember thinking, there are going to be people who do all of these things and there are still going to be walls, and I need to write to that. And so I wrote that line, but I did not feel like it was my book to write more than acknowledging that that also exists and that that should shift. I think I did address it in the way that was appropriate to my experience.

I’d love to know more about the logistics of writing a book as an active professional athlete. What does your time management look like?

I did a huge amount of writing on my honeymoon, which is funny, but it was when I wasn’t training, so that helped to have a period of time. I went to Italy and I was gone for a month. It wasn’t my whole honeymoon, but I did get to spend several days where the whole day could be dedicated to writing and that really helped. Other times when I wrote, I just made sure that I had a three- to six-hour chunk to write, which is not on a day when you’re doing a hard workout or you have a double. It’s a day when there’s a whole afternoon free. It takes some time to get into writing and it can’t be done in 30-minute chunks. And that was more challenging when I was training. But that was why the deadline for the book, I think, wasn’t as strict as someone who wasn't training.

How do you take care of yourself during busy periods of creative work and training? Do you have specific strategies and routines to prevent yourself from burning out?

I try to plan as much the day before as I can, and write that down. And on any given day, I need to know what my priority is. Most days, training is my number-one priority and everything is structured around that. But on easy days, for example, I’ve been able to be like, I write best in the morning. Maybe I can push my run to the afternoon, even if I have to run alone. As far as longevity, I think boundaries are important, like knowing I’m not going to stay up past 10 P.M. no matter what, because that will just create a domino effect. And then knowing that the cells only know effort. So sometimes I wouldn’t do my double because between the writing and the morning running, that was enough cellular effort for today. So I would say I probably have a 15-mile variation week to week, in the context of a 100-mile week. That kind of flexibility allowed me to give or take when I needed to. Cooking also really replenishes my willpower. I like the thought that something is baking in the oven while I’m writing. I like the smell of it. I like the thoughtfulness of it. There are things that I enjoy that make me feel like I’m thriving even during a busy time.

Has the running community been supportive of your multiple ambitions as an athlete and an artist?

Yeah, it depends. Now, yes. Early on, it was so important for me to perform well in both arenas separate from one another. To be a fast runner was important no matter what kind of creative dreams I had. And that was partly on me. I didn’t want to be given any sort of excuse to not win a race because of a movie that I had made. I wanted to be performing and chasing that Olympic dream. I think once I was able to have a movie in the Sundance Labs and perform well, for better or worse, people started to get on board.

I’ve been super grateful to people like Shalane Flanagan. When she read the book, she blurbed it, but she also called me and was like, “I felt like you were in my head.” I was driving to a workout and I just pulled over and we talked for over an hour. And that meant a lot to me because it’s OK if not everybody believes in you or what you’re doing, but it is really lovely and it is really a gift when some people do and when those people are people you admire.

So what’s next for you in running and in your creative work?

I have the book release, and then I’m speaking at South By Southwest this year as a featured speaker, and I’m very excited for that. And we have a big TV project we’re working on, which is almost like changing events in running—it’s the same sport, but a different event. And some movie projects that I’m doing with bigger and bigger teams. So I don’t have to wear every single hat anymore.

And then I’m running. I want to be in Tokyo. I think it’s going to take a race in late spring. And I have hope that something will be there for me to race. But I also respect that the world is the way it is. So right now, I need to be nimble and agile. I think later in the spring there’ll be some races. Women still have to qualify, but I respect that the world needs to do the responsible thing.

This interview has been edited and condensed.