This story was republished on Jan. 4, 2022 to make it free for all readers

By the time a woman reported Kalan Haywood Sr. to police for sexual assault in the summer of 2019, he had become a well-known leader in Milwaukee's Black community. His real estate development firm, The Haywood Group, got $9 million in taxpayer-backed loans that year — one of them after police opened an investigation into the rape complaint against him.

Haywood planned to use the money for a boutique hotel, the Ikon, on the city's north side. It would be the first hotel built by a Black developer in Milwaukee — one of the most segregated cities in the nation — and it would be located in a neighborhood largely populated by poor Black residents. Rocky Marcoux, then the city development commissioner, talked about the significance of those factors when the Common Council approved Haywood's first loan for the Ikon.

"The folks you'll see working on this building are going to look like the people in this community," Marcoux told council members. "That means a lot, not only to the people who live here but to the rest of Milwaukee as we try to advance men and women of color in the development (and) construction trades, and … (in) actually sharing in the success of what's happening downtown and in other parts of the city."

The terms called for Haywood’s LLC to repay the money over 20 years, with the first payment due in fall 2021. One of the aldermen who voted against the loan said the city was potentially "throwing money away" because Haywood hadn't provided enough evidence of how he would repay it. The city had sued him in small claims court several times previously, and he'd failed to pay his taxes on time more than once.

Once the loan was approved, city officials had an incentive to help Haywood succeed. If he failed, it could cost Milwaukee taxpayers millions.

Haywood has sold his life story as making the most of a second chance.

Raised by his grandmother in Brewers Hill, Haywood graduated from Riverside High School. He enrolled at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee but hung out in the streets when he wasn't in class.

At 21, Haywood was arrested for possession of cocaine and carrying a concealed weapon. He was convicted and sentenced to three years in prison. After his release, he has said, he went back to his old life and was shot multiple times.

“I still get asked constantly about my case from 1995,” Haywood told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel in 2019. “Every deal I do. Every single deal. Well, I did that. It's my fault. I’m willing to explain it every time.”

He credited a mentor with helping him go straight.

At first, Haywood focused on flipping neglected houses. In 2000, he started his first real estate development firm, Vanguard Group LLC, and turned his sights to retail properties, including a Walgreens store in the 2800 block of N. King Drive.

He also led an effort to convert the historic Germania Building downtown from offices into apartments with help from the city — $1.5 million.

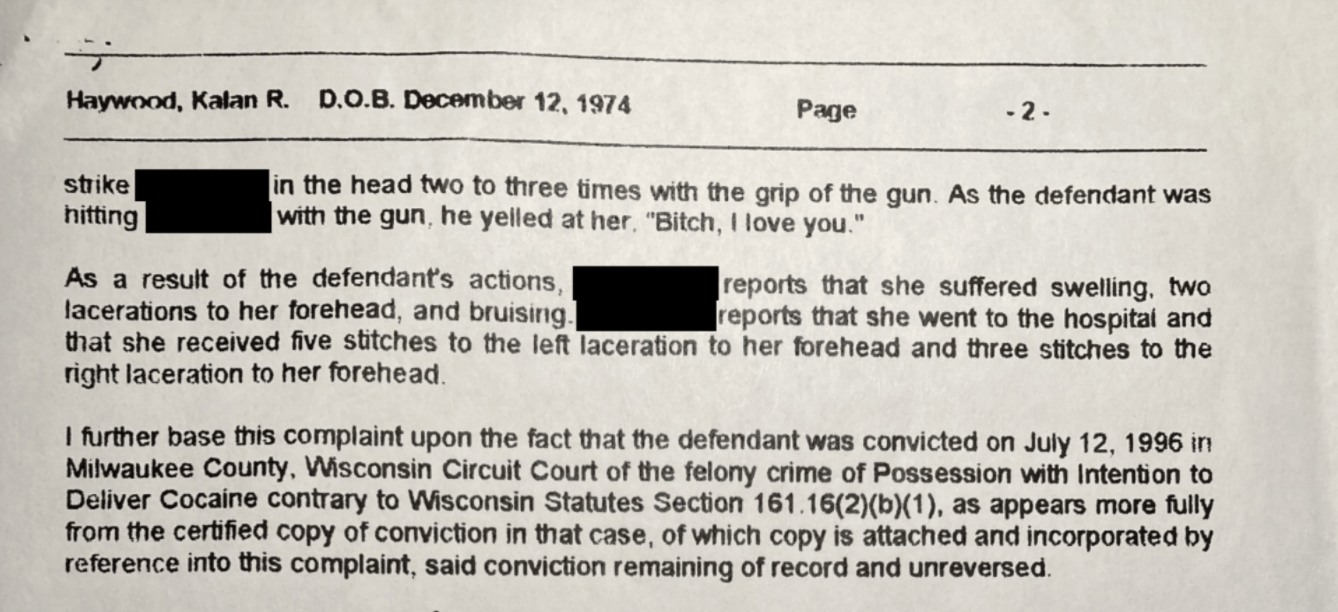

Haywood doesn’t mention a 2006 criminal case when he tells his redemption story. That year, he was charged with pistol-whipping a girlfriend.

According to the criminal complaint, Haywood punched the woman in the head approximately 10 times in front of her 8-year-old daughter.

Haywood yelled, “Bitch, I love you!” as he then slammed her head with a gun, the complaint says. She needed eight stitches.

Two felony charges were dismissed when the woman failed to show up for a court hearing.

Victims often are unwilling to testify against abusers for a variety of reasons: fear, stigma, losing custody of shared children, being deprived of housing or financial support, or religious or family pressure. Because of this, Wisconsin law permits “evidence-based prosecution.” This method allows the district attorney to make a case by presenting other proof, such as photographs of injuries and testimony from police officers or health care providers.

But the woman who accused Haywood in 2006 didn’t just refuse to testify. Two years after the charges were filed, Haywood's attorney, M. Nicol Padway, produced a sworn statement signed by the woman, which said she did not want to go forward.

Padway was a former member of the powerful civilian Fire and Police Commission. During a seven-year tenure on the board that ended in 1994, Padway said, he made it a point not to represent criminal defendants in Milwaukee cases.

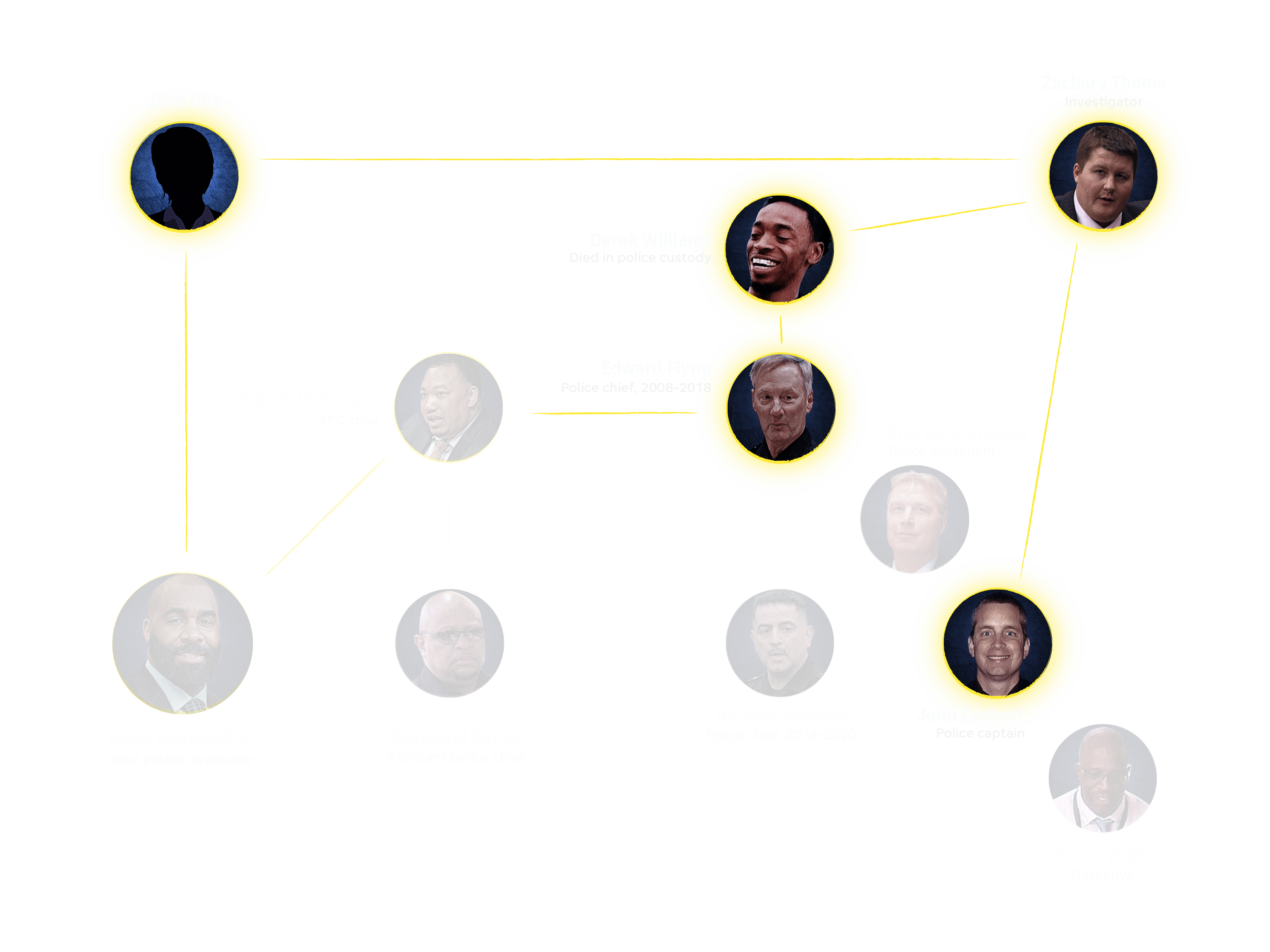

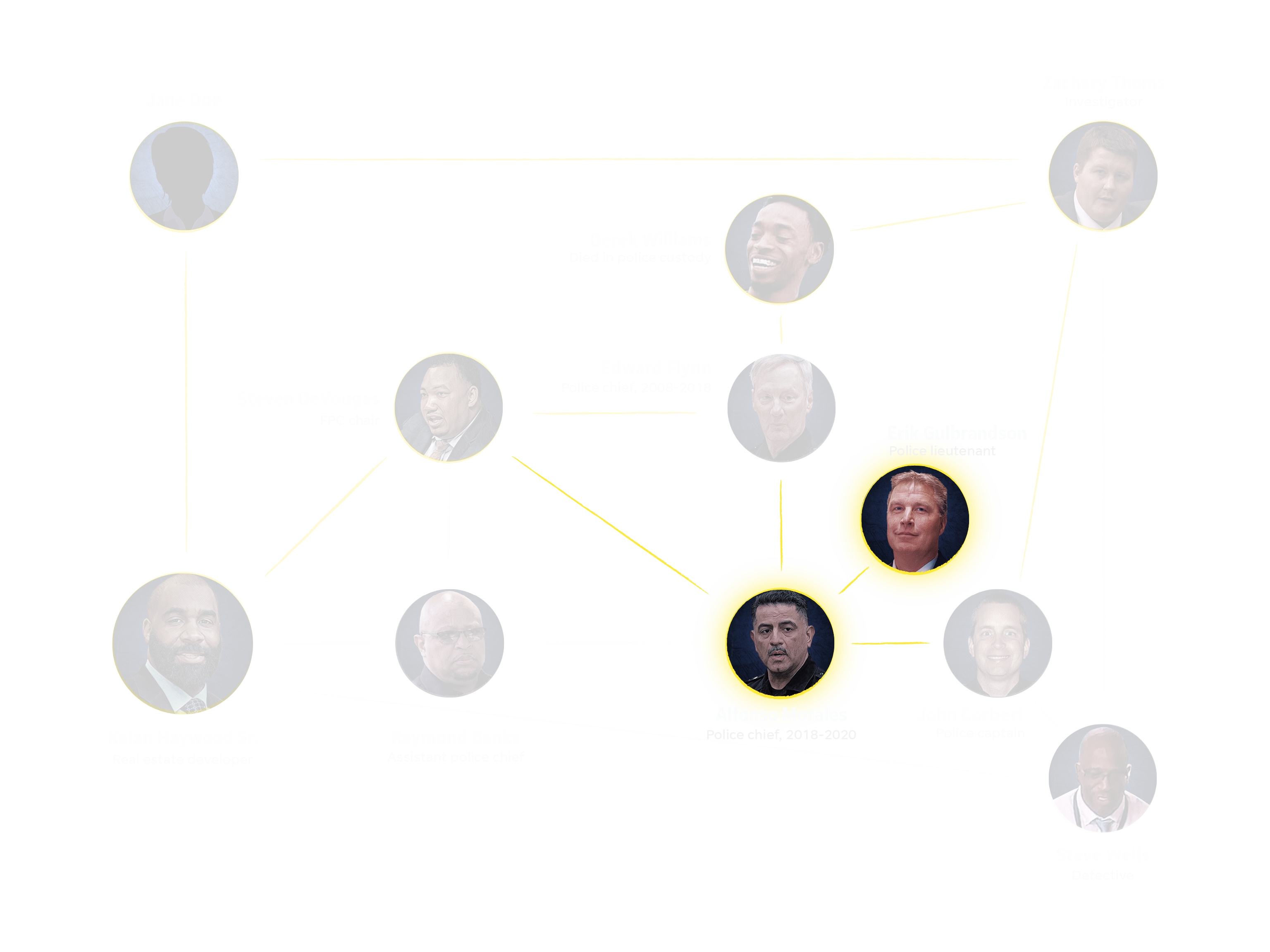

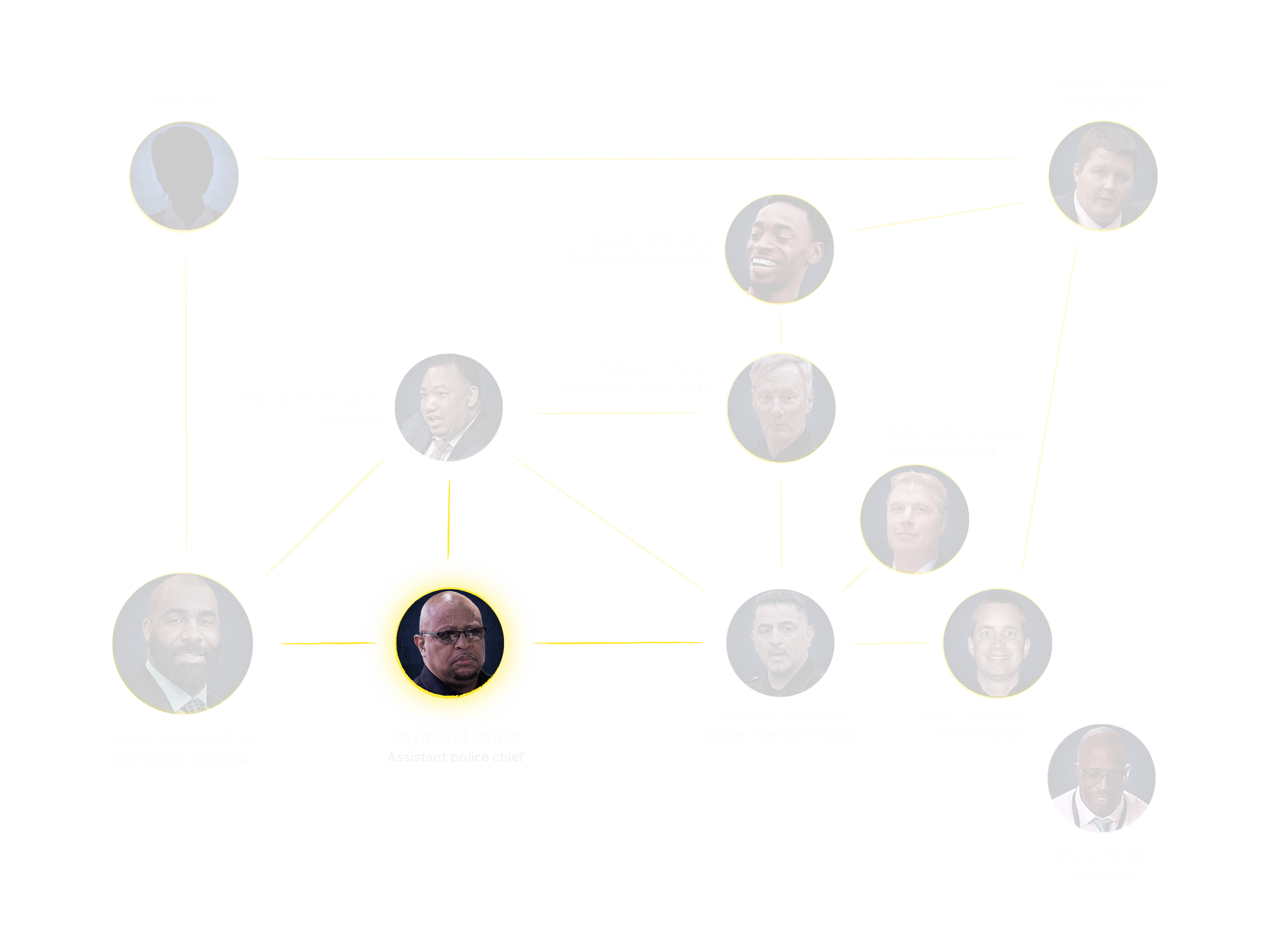

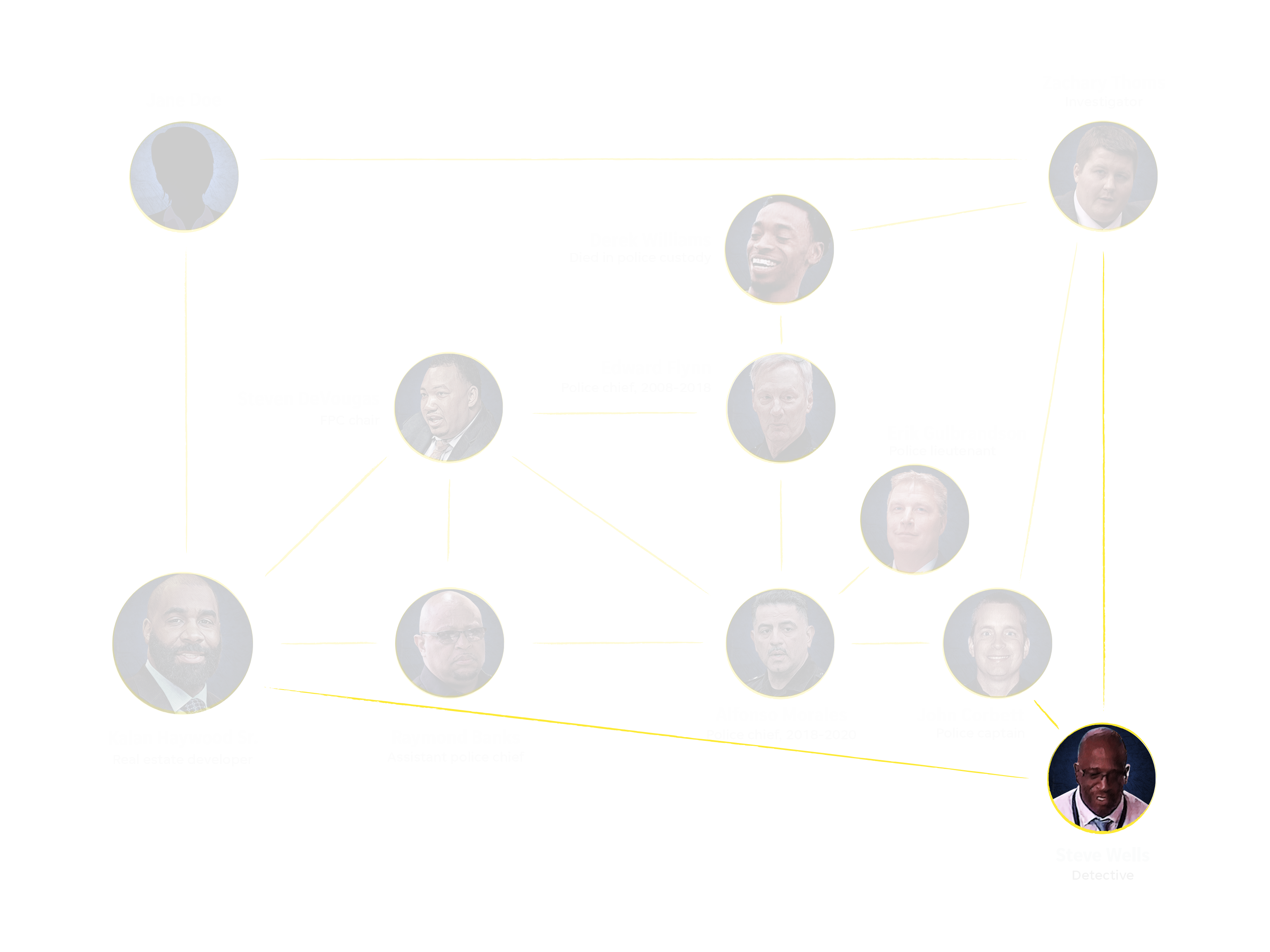

The next time Haywood retained a lawyer with ties to the commission, he turned to Steven DeVougas, its chairman, whom he hired as a real estate lawyer in 2017.

Later, the police detective who questioned Haywood about a rape allegation would say he didn't know DeVougas worked on criminal matters.

The attorney replied: "I do it all."

Cops with troubled histories

The Milwaukee Police Department has long faced criticism for lax discipline of problem officers, but there's plenty of blame to go around.

While chiefs have the authority to fire cops for misconduct, they don't always use it. Even when they do, both the Fire and Police Commission and the courts have the authority to overrule them. One basis is fairness. If other officers have racked up similar violations but kept their jobs, a termination may not hold up. As a result, the department's history of letting bad cops slide makes it harder to hold today's force accountable.

Two of the officers responsible for investigating Jane Doe's sexual assault complaint against Haywood had narrowly avoided being fired.

One was lead investigator Zachary Thoms, whose promotion to detective was denied by the Fire and Police Commission after he was involved in one of the worst and most expensive scandals in the Police Department's history.

Between 2007 and 2012, officers in District 5 on the city's north side performed dozens of illegal strip and cavity searches — most on Black men. Four white officers were criminally convicted as a result. The city has paid out more than $5 million in legal claims to dozens of victims. Because the city is self-insured, that money all came from taxpayers.

Thoms avoided criminal charges after he agreed to cooperate with prosecutors. He told them he and another officer — who was later convicted of multiple felonies and sent to prison — had coerced a suspect to try to defecate into a cardboard box in the hopes he would expel drugs.

None were found.

Another man had accused Thoms of reaching into his pants and retrieving a plastic bag of drugs from his anus in 2011, but those claims were dismissed by a federal judge.

Thoms' deal with the Milwaukee County District Attorney’s Office also expressly included a promise he would not be disciplined by the Police Department.

Such agreements are "very rare," Chief Deputy District Attorney Kent Lovern said at the time, but this one was necessary to obtain convictions against Thoms' four fellow officers.

His attorney, Brendan Matthews, said Thoms deserved credit for telling the truth.

"It was messed up," Matthews said at the time. "But how many times do people see messed up things in their lives and they don't do anything about it? I know police officers are held to a different standard, but at the end of the day, they're just people."

Thoms' cooperation in the strip search investigation, which came in 2014, marked the second time he spoke up against other cops amid misconduct claims. A year earlier, he testified during an inquest into the death of Derek Williams, who died after gasping for breath and begging for help in the back of a squad car. Five other officers and two sergeants refused to testify, citing the Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination.

When Jane Doe filed her report, Thoms’ boss in Sensitive Crimes was John Corbett, another cop with a troubled history.

In November 2010, Corbett was arrested after he got drunk and let his 13-year-old daughter drive his car. He was convicted of a criminal misdemeanor and served 30 days on work release, doing his job as a police sergeant by day and sleeping in the jail. He also was suspended from the department for 60 days.

After he got sober, Corbett was promoted twice, once by Edward Flynn and again by Alfonso Morales, who took over as chief in February 2018. Both times, the Fire and Police Commission approved. One of the board members said they were impressed with Corbett's efforts in recovery, which included earning a master's degree and providing private substance abuse counseling to law enforcement.

Building a new fundraising foundation

Doe never anticipated that her rape complaint would get tangled up with the police chief's efforts to raise money. But because of Haywood's connections, it did.

Creating a new nonprofit, the Milwaukee Police Foundation, was among Morales’ earliest goals as chief. It was inspired by the St. Louis Police Foundation, which collected nearly $2.5 million in 2018 to pay for training and equipment such as ballistic vests and surveillance cameras.

In Milwaukee, Morales had grander plans. He wanted to raise tens of millions for a new regional police training facility, and he put Lt. Erik Gulbrandson in charge of making it happen.

A volunteer attorney registered the new nonprofit with the state in April 2019. The next steps were recruiting board members and soliciting donations.

But the fundraising got off to a slow start.

According to its tax return for 2019, the foundation took in just $12,050 that year, including $5,000 from the Greater Milwaukee Foundation and $5,000 from a board member who ran a construction company. The document lists spending of $153 on “analysis fees” and $1,172 for an “MPD meet and greet.”

The foundation's conflict of interest policy lays out what to do if a board member becomes financially involved in its operations.

It doesn’t say what should happen if someone who makes a large donation ends up arrested or if one of the board members is accused of a crime.

- Document: Form 990, Milwaukee Police Foundation

- Document: Milwaukee Police Foundation, conflict of interest policy

Allegations of sexual harassment

Haywood's law enforcement connections didn't end with DeVougas and the Fire and Police Commission. Haywood was also longtime friends with Raymond Banks, an assistant chief of police. The three of them, the Fire and Police Commission's executive director later said, "appeared to be close."

Morales invited Haywood to join the Milwaukee Police Foundation's board at the suggestion of Banks, whom Morales had promoted despite a sexual harassment complaint by a Black female officer.

Banks denied the woman's allegations. In a conversation with Morales, Banks said his interactions with her were “not sexual in any manner and it was not his intent to make her feel uncomfortable,” the chief wrote in a memo to the Fire and Police Commission.

The commission, chaired by DeVougas, approved Banks' promotion with little discussion in April 2018, a month after the police union representing Banks' accuser had hand-delivered her harassment claim to commission staff.

In that complaint and another to internal affairs, the woman said Banks had tormented her for years, making sexual comments, calling her at home to proposition her and barging into her office uninvited.

The woman made the report reluctantly, worried it could harm her career. As it turned out, she was right. She initially took medical leave, saying she was too traumatized by Banks’ conduct to continue working. Later, Morales fired her.

According to a notification presented to the Fire and Police Commission in 2019, he did so for "non-disciplinary fitness reasons." After the vote to affirm the woman's firing, DeVougas told a reporter that, in general, those reasons could be anything other than misconduct.

"It could be for health reasons, it could be for personal reasons," he said at the time. "It's kind of a catch-all."

Asked if the public might consider that explanation vague, DeVougas said he didn't know "if that necessarily involves the public purview."

City officials later approved a taxpayer-funded legal settlement of $16,500 with the woman.

The chief wants answers

Haywood's membership on the Milwaukee Police Foundation's board was slated to become official at the group's August 2019 meeting. Not long before that, Morales’ chief of staff gave him some troubling news: A woman had recently filed a sexual assault complaint against Haywood.

Morales wanted more information. If Haywood was named to the board amid a rape investigation, the optics could turn out to be very bad.

The lieutenant spearheading the project called Corbett, the sensitive crimes captain, and asked him for answers.

Corbett said the case was awaiting a charging decision by the district attorney’s office. A search warrant remained outstanding and Haywood still needed to be questioned.

Corbett later got another call. This time, it was the chief himself.

Morales explained Haywood’s connection to the Milwaukee Police Foundation's board and indicated he wanted to keep the case moving, Corbett later recalled. It was the first and only time he got a call from Morales about a specific case.

Morales defended his actions in an interview with the Journal Sentinel last summer.

“I don’t want to get myself caught up in saying something I shouldn’t be saying,” he said. “It’s not my job to let somebody know ‘Hey, you’re under investigation.’ I have to find out what my boundaries are.”

A poorly timed interview

Corbett arranged for Detective Steve Wells to question Haywood in the hours before the foundation's board meeting on Aug. 13, 2019.

Both Thoms, the lead investigator, and the assistant district attorney assigned to the case were on vacation. Neither agreed with the timing. Haywood had no idea he was under investigation, which was to their advantage. If he found out too soon, he could hide evidence or otherwise compromise the case.

Although Morales later said he didn't have a problem with Haywood being interviewed under those circumstances, several national experts told the Journal Sentinel it was a questionable choice.

“When the prosecutor and the lead investigator are still planning the investigation and there’s still information they want to get, I would defer to them,” said Ronal Serpas, who has led the police departments in New Orleans and Nashville and serves on the national Council on Criminal Justice.

He added: “A poorly timed interview could tip off the suspect before you know what you might find.”

The prosecutor wanted Corbett to explain things to the victim, so he got on a call with both of them. Doe begged that her name not be disclosed to Haywood, saying she was afraid of what he might do.

She says Corbett assured her it wouldn’t.

But his promise was quickly broken.