‘It’s a profession that does not love you back’: Nursing home staffs bear witness to staggering death tolls

They care for their patients for years sometimes, getting to know their families. Now, a shortage of PPE and a lack of testing puts them all at risk.

Listen 3:14

Residents from St. Joseph's Senior Home are helped on to buses in Woodbridge, N.J., Wednesday, March 25, 2020. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

Are you on the front lines of the coronavirus? Help us report on the pandemic.

Outside the nursing home where Julie Moore works, there are no signs thanking heroic health care workers. No volunteers bringing trays of hot food or homemade masks to her colleagues. Instead, day in and day out, there are ambulances. They pick up residents, take them to the hospital, and bring them back.

Over the past two months, Moore has cared for and seen more people die from COVID-19 than many hospital workers have. When the tally rose past 40, she says, she stopped counting.

“We call it a ghost town,” said Moore, who has worked as a nursing assistant in hospitals, hospice, and skilled-nursing facilities for 20 years. “You come in and it’s a quiet day on the job, and you realize, ‘Oh, Mr. Such-and-Such normally sits here.’ And it’s like, ‘Wow.’”

A nursing facility differs from a hospital in that, for most patients, it’s home. People live there for a long time and develop relationships with the staff members who bathe them, groom them, help them eat, and take them to the bathroom. They keep in touch with residents’ families and care for them in the last days of their lives.

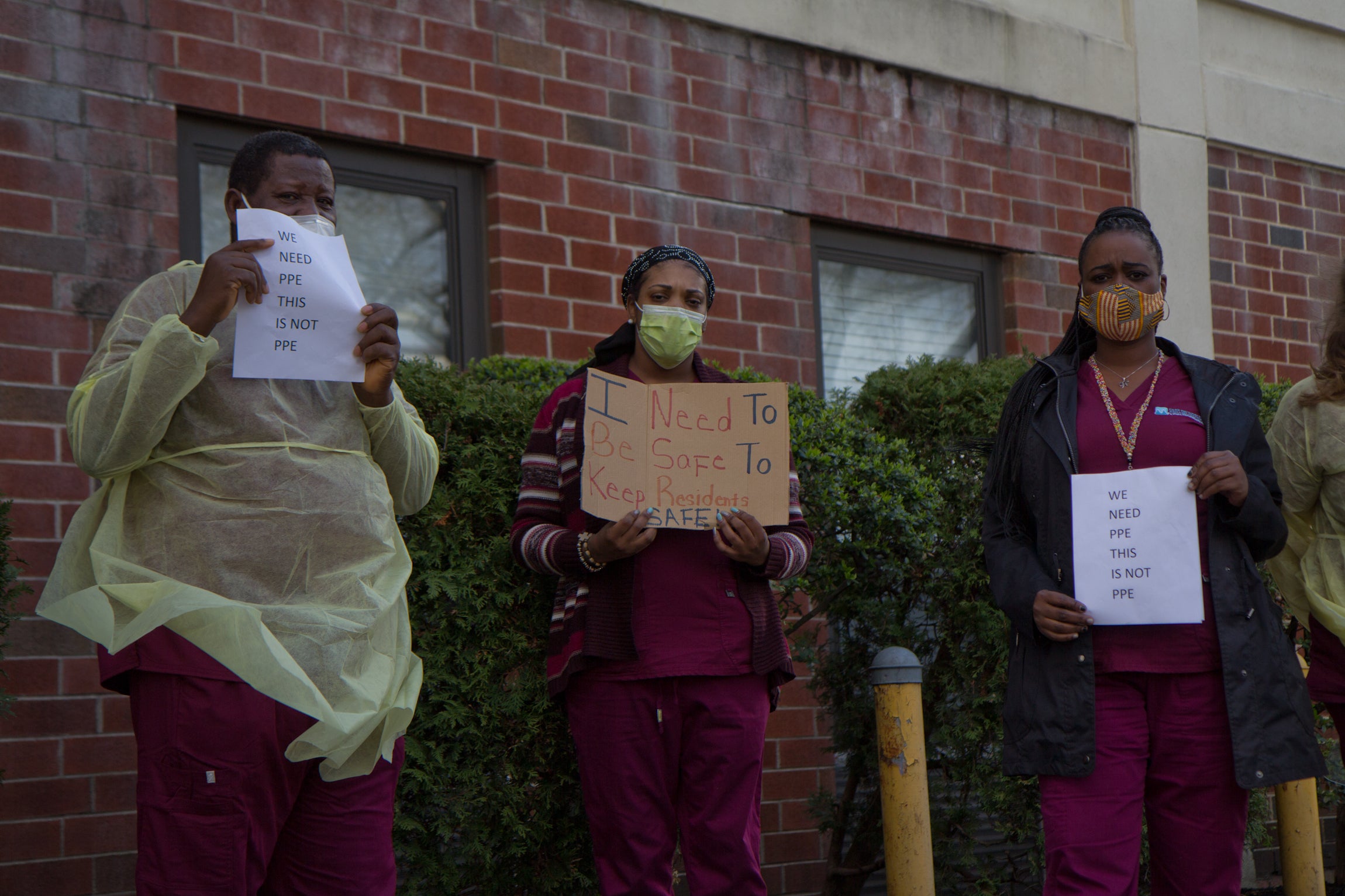

And yet a shortage of personal protective equipment, low staffing levels, and a lack of testing have put the employees of long-term care facilities at enormous risk throughout the course of the coronavirus pandemic.

‘Like a chess game’

At her facility, which she did not want to name for fear of professional repercussions, things changed fast, Moore said. She might have been caring for a patient one day, have the next day off, then come back to find a “droplet precaution” sign on the person’s door, meaning that patient was a suspected COVID-19 case.

But that meant the patient was contagious before he or she was isolated.

In Pennsylvania, the state Department of Health does not recommend that employees wear personal protective equipment such as gowns and masks when caring for patients who do not have COVID-19, as a means of conserving the gear. But because the virus spreads asymptomatically, it’s impossible to know if someone is truly positive or negative where there are outbreaks. That presents workers with an impossible choice: follow guidelines and go in unprotected, risking their own exposure and the potential of passing on the virus, or reuse PPE and risk spreading the infection among patients. There simply isn’t enough PPE to change between patients.

“Maybe you put one gown in the north side and one gown for all affected patients on the south side,” said an employee at Inglis House, a long-term care facility in Philadelphia that treats people with quadriplegia or paraplegia but not the elderly. “Sometimes, you just say a prayer and keep moving.”

Most nursing homes are not in a financial position to order personal protective equipment in bulk, said Adam Marles, president and CEO of LeadingAge PA, a trade association for nonprofit aging-services providers. Because of broken and unreliable supply chains, he said, suppliers are likely to request money up front, without a guarantee the order will ever arrive.

“There is no greater need right now than that gear,” said Marles.

Nursing homes are largely cash-strapped now because many depend on revenue generated from short-term rehabilitation patients, of which there are fewer since hospitals canceled elective procedures.

Experts say that in an ideal setting, a nursing home would have a separate physical wing, or even a separate building, for coronavirus patients, with its own entrance, HVAC unit, and designated staff. But most nursing homes don’t have the staffing or supplies to do that, so instead, they do the best they can.

Moore, as well as the Inglis House employee and others, said that while facilities often designate COVID floors or wings, not everyone with COVID-19 is always placed in the designated areas, especially if moving the patient would be more disruptive. And even if there is a specific unit, they said, there isn’t enough staff to dedicate a cadre of housekeepers, nurses and aides to attend only to those patients.

A paramedic for Romed Ambulance Service, whose name WHYY News agreed to withhold because the employee was not authorized to speak publicly, said their team had been shuttling nursing home patients with COVID-19 from long-term facilities throughout the Philadelphia region to hospitals and back multiple times a day over the last few months, often placing patients back in their original rooms, with their original roommates.

With widespread testing, asymptomatic roommates or even neighbors across the hall could be checked for the virus. But most nursing homes don’t have access to tests for asymptomatic patients.

“It’s like a chess game,” said Sunil Chako, the administrator at Renaissance Healthcare & Rehabilitation Center in Philadelphia, which had the first documented coronavirus case among nursing homes in the city. “You have to be ahead of it.”

Chako said because their cases occurred early on, the city’s Department of Public Health was able to help test residents widely. Knowing who had the virus before waiting for symptoms to develop helped them know who needed to be isolated, and they could dedicate staff accordingly.

Although five patients at Renaissance died, 17 have made full recoveries, and the facility hasn’t seen a new case since March 31, according to Chako.

While some states like Maryland and Wisconsin have prioritized testing of all residents and staff in congregate care settings, Pennsylvania and New Jersey have not. Of the 3,012 COVID-19 deaths reported by the Pennsylvania Dept of health as of Tuesday night, two-thirds were among nursing home residents, as were more than half of New Jersey’s 8,244 deaths.

Fewer workers, more work

Nationally, nursing home aides earn $14.25 an hour, on average. Because the work is hard and the pay is low, there isn’t a reserve of staff waiting to be called up in a time of crisis the way there is for doctors and nurses, said Josh Uy, the medical director at Renaissance and a professor of geriatric medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

“When 50% of staff have to stop working, nursing homes have to do more with less,” said Uy.

“As a society, we haven’t trained enough people to work in nursing homes, so there’s nobody to provide help when it’s most needed.”

Laurie Facciarossa Brewer, New Jersey’s long-term care ombudsman, said the pandemic isn’t likely to make the work more attractive either.

“There is, for sure, a nursing shortage and a nursing assistant shortage,” she said. “This situation certainly has exacerbated that.”

At the peak of the coronavirus’s spread in Julie Moore’s facility, 60% of staff were out. Staff are in short supply at long-term care facilities because handling sick patients gets them sick. Many also care for older relatives of their own, and are worried about bringing the infection home.

But just as the staff was in short supply, the intensity of work was ramping up. Nursing home attendants might check an otherwise healthy patient’s vital signs once a week; with COVID-19, they wanted to check every few hours to make sure someone’s condition had not worsened.

The work itself was exhausting in a different kind of way, both emotionally and physically, said Moore. Wearing the gowns and masks between patient rooms was awkward, she said. Often, disoriented patients suffering from dementia were confused, and she needed to explain why she was masked up.

“I can’t smile because they can’t see it, but I try a little head rub or something, to make them feel comfortable, and I make sure I keep checking on them,” she said.

Other times, Moore said, patients were offended that she would think she needed to protect herself from them. Some watched the news, knew exactly what was going on, and the virus became the unspoken elephant in the room.

“Nursing is a profession that does not love you back,” Moore said.

Mildred Ives, a 72-year-old longtime resident at the River Run Healthcare and Rehabilitation Center in Kingston, Pennsylvania, said she feels for the staff that care for her and her neighbors. She said she and other residents like the rooms to be kept toasty, and can only imagine how uncomfortable that might get for the staff.

“The goggles don’t help a lot because they steam up because of the mask, and the steam comes up onto them and it makes it even worse for them,” said Ives.

“I guess I know how astronauts feel with the gear on because it’s so hot, it takes a lot out of you,” Moore joked.

Ives said she is grateful that the staff at her facility have gone above and beyond to maintain the single common staple of the social lives of nursing home residents across the country: bingo.

Normally played in a gathering hall or cafeteria, staff at Ives’ residence have started bringing personal bingo cards to residents’ rooms, plus a separate slip of paper with the numbers that would have been called.

“I know they do everything they can,” Ives said.

Moore understands how hard it can be for families to feel connected to their loved ones with a strict no-visitor policy. So if she happens to see a family outside who might be trying to catch a glimpse of a loved one through the window, she’ll offer to take a phone up to the patient’s room, snap a photo, or even start a FaceTime session, and bring it back down for the family.

“I know how hard it is not to see my kids for just a 16-hour shift, so I can imagine how hard it would be to not have any contact or communication,” said Moore, who has an 8-year-old and a 19-year-old at home.

Between caring for her kids and the emotional toll at work, Moore said she’s exhausted. Each time someone has died of COVID-19, her first instinct is to replay everything that happened and wonder if she could have done something differently.

“At the end of the day, there wasn’t anything we could have done,” she said. “This thing came in like a roller coaster and had us all on a really long ride. And we’re still on it.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)