The California Dream Is Dying

The once-dynamic state is closing the door on economic opportunity.

Updated at 7:30pm ET on July 30, 2021.

Behold California, colossus of the West Coast: the most populous American state; the world’s fifth-largest economy; and arguably the most culturally influential, exporting Google searches and Instagram feeds and iPhones and Teslas and Netflix Originals and kimchi quesadillas. This place inspires awe. If I close my eyes I can see silhouettes of Joshua trees against a desert sunrise; seals playing in La Jolla’s craggy coves of sun-spangled, emerald seawater; fog rolling over the rugged Sonoma County coast at sunset into primeval groves of redwoods that John Steinbeck called “ambassadors from another time.”

This landscape is bejeweled with engineering feats: the California Aqueduct; the Golden Gate Bridge; and the ribbon of Pacific Coast Highway that stretches south of Monterey, clings to the cliffs of Big Sur, and descends the kelp-strewn Central Coast, where William Hearst built his Xanadu on a hillside where his zebras still graze. No dreamscape better inspires dreamers. Millions still immigrate to my beloved home to improve both their prospects and ours.

Yet I fear for California’s future. The generations that reaped the benefits of the postwar era in what was the most dynamic place in the world should be striving to ensure that future generations can pursue happiness as they did. Instead, they are poised to take the California Dream to their graves by betraying a promise the state has offered from the start.

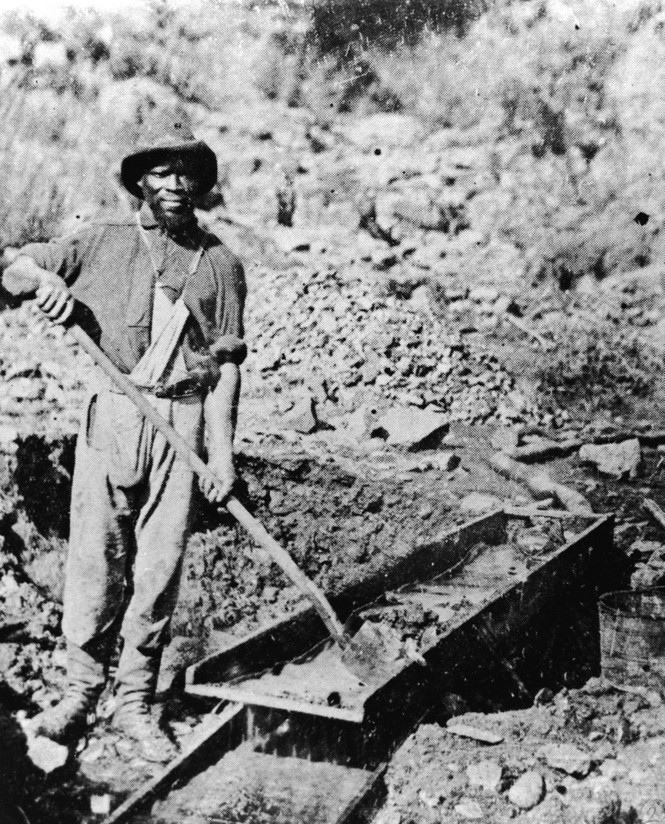

The writer Carey McWilliams captured that promise in California: The Great Exception, the definitive celebration of California’s founding myth—the way the Golden State long preferred to understand itself. Published in 1949, just ahead of the state’s centennial, it told the story of California’s rise from a sparsely populated Spanish territory to a world-altering force. McWilliams’s tale begins on the eve of statehood with the discovery of gold on a river near the western slopes of the Sierras. That find sparked the Gold Rush and then a mass migration that transformed the Pacific Rim. Northern and southern whites mingled with free Blacks, runaway slaves, newly naturalized immigrants, and foreign dreamers from the Americas, Asia, Australia, and Europe. “We have here in our midst a mixed mass of human beings from every part of the wide earth, of different habits, manners, customs, and opinions, all, however, impelled onward by the same feverish desire of fortune-making,” wrote Peter H. Burnett, who soon became the state’s first governor.

By 1850, when California entered the union with a constitution that banned slave labor by consensus, the features that would define the state were already established: It attracted a wildly diverse population and offered everyone save its Native tribes unprecedented opportunity, if not yet equal rights. California, the social scientist Davis McEntire observed, meant to America what America meant to the rest of the world.

The Gold Rush made San Francisco a global capital. And in its earliest years, the city was more closely connected to the Pacific Rim than to the East Coast establishment, permitting it to enter the global stage on its own terms. “Of all the marvelous phases of the Present,” the poet Bayard Taylor wrote, “San Francisco will most tax the belief of the Future,” as it “seemed to have accomplished in a day the growth of half a century.” In the 1850s, McWilliams wrote, the city published more books than the rest of the U.S. west of the Mississippi, printed more newspapers than London, and popped seven bottles of champagne for each one opened in Boston, thanks to North America’s highest per capita income. Circa 1860, with the transcontinental railroad incomplete and the Panama Canal a distant dream, four people out of five residing in California were born elsewhere. Mexicans had just been overtaken as the largest foreign-born group––that year, every 10th person in California was Chinese, and both would soon be overtaken by the Irish.

The easy gold didn’t last forever, but the state continued to thrive. “In California the lights went on all at once, in a blaze,” McWilliams wrote, “and they have never been dimmed.” Across its first century, California kept attracting fortune seekers both foreign and domestic, its population always growing. Then came World War II and the postwar boom, transforming Southern California as dramatically as the Gold Rush had changed the Bay Area.

Of course, that celebratory narrative elides California’s many failures to do right by its wildly diverse inhabitants. The Gold Rush devastated Indigenous people in mining regions and coincided with atrocities against Native tribes. Californians later played an outsize role in lobbying for the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act. During the 1930s, Angelenos were so resistant to Dust Bowl migrants that they deployed a posse of Los Angeles Police Department officers to the state lines to turn back “Okies” and other “undesirables.” And Japanese Americans were forced into internment camps during the war years. Yet even when its intolerance was waxing rather than waning, the state was often more diverse and inclusive than the rest of the world.

On one hand, Jefferson Edmonds, the editor of a newspaper serving Los Angeles’s Black community, declared in 1902 that “California is the greatest state for the Negro,” and W. E. B. Du Bois echoed the sentiment in 1913, writing,

Los Angeles was wonderful. The air was scented with orange blossoms and the beautiful homes lay low crouching on the earth as though they loved its scents and flowers. Nowhere in the United States is the Negro so well and beautifully housed, nor the average efficiency and intelligence in the colored population so high. Here is an aggressive, hopeful group––with some wealth, large industrial opportunity and a buoyant spirit.

On the other hand, the optimism of African Americans who moved to the state in the first decades of the 20th century gave way to feelings of betrayal at subjugation, famously boiling over in riots in 1965 and again in 1992.

As recently as the 1990s, the state appeared to be trending less toward easygoing diversity than toward violent balkanization and draconian crackdowns on undocumented immigrants. As murders spiked, doomsayers talked as if additional newcomers would make the state more dangerous.

Yet more immigrants came. Those most uncomfortable with diversity left. Crime fell significantly. And the xenophilia that followed––the relaxed attitude so many Californians exhibit in the face of difference––is a triumph. Californians are more committed than ever to equality under the law. Past mistreatment of Indigenous peoples, Chinese nationals, African Americans, Dust Bowl transplants, Japanese Americans, Hispanic immigrants, gays and lesbians, and trans people are now appropriately sources of shame. Enormous inequalities of opportunity remain, and the state is far from perfect. Still, California continues to welcome fortune seekers of widely varying backgrounds, and has never come so close to living up to half of its mythic inheritance.

But even as California began to truly embrace its diversity, laying part of the foundation for a better future, the state’s leaders and residents shut the door on economic opportunity, betraying the other half of the state’s foundational promise. They forgot that California has always thrived by embracing both cultural and economic dynamism. There are still neighborhoods enough to house the wealthy. The brightest still thrive at Stanford, Berkeley, and UCLA. Tech investors and innovators still strike gold in Silicon Valley. Alas, the economic prospects for the typical resident have dimmed. Millions of people lack adequate housing, education, or jobs. College-educated Millennials can’t afford homes of their own. Poverty-stricken Californians dwell in growing tent cities. During the pandemic, something occured that McWilliams would have found unthinkable: a net loss in population. California is still forecast to add millions of additional residents in coming years, but though they may be treated more equally than in the past, the state is unprepared to offer them upward mobility.

If California fails to offer young people and newcomers the opportunity to improve their lot, the consequences will be catastrophic—and not only for California. The end of the California Dream would deal a devastating blow to the proposition that such a widely diverse polity can thrive. Indeed, blue America’s model faces its most consequential stress test in one of its safest states, where a spectacular run of almost unbroken prosperity could be killed by a miserly approach to opportunity.

Russell Renier was born on the eve of the Depression to a poor Cajun family in Lafayette, Louisiana. World War II ended just before he was old enough to be drafted. Finishing high school on the hot, humid bayou offered less promise or appeal than striking out for Los Angeles. Arriving in 1946, he quickly found a gig sweeping floors, and then moved on to a more promising job in construction.

There was no better time to start out in the state’s building trade. The newcomers who flocked to California after World War II were straining its infrastructure. “The stampede has visited us with unprecedented civic problems,” Governor Earl Warren explained in August 1948, “partly because even if we had been forewarned we could have done but little to prepare for the shock during the stringent war years. So we have an appalling housing shortage, our schools are packed to suffocation, and our highways are inadequate and dangerous. We are short of water and short of power.”

Scarcity tends to fuel resentment. But Californians of the late 1940s could hardly turn against the young people who had just fought the Axis powers to unconditional surrender or toiled in the war industry. The period was remarkable in part because it showed that enormous influxes of newcomers could be accommodated––even in a state overwhelmed by a “stampede”––when majorities feel obligated to allow them opportunities to make good lives for themselves, in part by building up the state on their behalf.

Renier did his own stint in the military. The Army drafted him to fight in Korea, then sent him to Berlin instead at the last minute. Returning to L.A. two years later, he began to master carpentry, framing doors and windows; putting cabinets in kitchens and bathrooms; installing baseboards. His wife, Doris, a fellow French Catholic from Louisiana, gave birth to two daughters. They surveyed all of Southern California trying to decide on the best place to buy a house, before settling on Orange County. With Walt Disney’s new theme park rising among Anaheim’s citrus groves, the county’s future seemed assured. One housebuilder, an acquaintance, was developing a new tract in nearby Costa Mesa. Would Renier do the finish work on the homes if he could get a double lot on the street of his choice?

Starting in 1963, he designed his own house, calling on friends in the industry to help him build it. Later, his daughter, Diane, met a boy from the neighborhood, Lee, a fellow first-generation Californian whose family hailed from Indiana. Diane and Lee are my parents.

Renier’s story illustrates what used to be a simple fact of life in California: With hard work, you could come here without a diploma and find an affordable place to raise a family of four on a single earner’s salary. At 41, though, I’d be hard-pressed to buy a home in the neighborhood where my grandfather built his house and where my parents bought theirs three decades later.

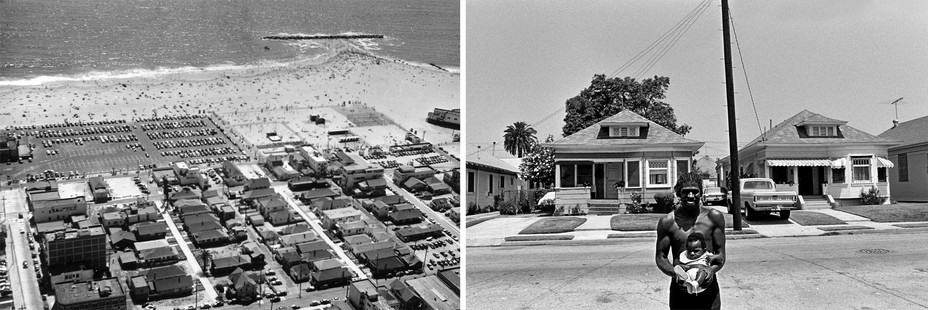

What has changed is captured even more vividly in Venice Beach, where I rented a house for seven years. Its famed boardwalk is among the most popular tourist destinations in the world. Each day, tens of thousands traverse its singular promenade, people-watching amid a chaotic mix of pedestrians, vendors, skateboarders, weightlifters, basketballers, cyclists, transients, pit bulls, and more. Yet the population of this oceanfront neighborhood is smaller than it was back when my grandfather was a carpenter. From 1960 to 2010, as the population of metropolitan Los Angeles increased by 91 percent and the city itself grew by 53 percent, the population of the 90291 zip-code area, which contains most of Venice, shrank by 20 percent, according to analysis of population data by the urban-planning researcher Dario Rodman-Alvarez.

How does one of the most desirable areas in Los Angeles experience a falling population and skyrocketing rents even as the city as a whole and the region around it explode in growth?

Frank Murphy understands the situation as well as anyone.

He moved to East L.A. in 1975, intending to be a potter, and began driving to Venice to help the conceptual artist Chris Burden, who wanted to build a tiny car that would go 100 miles an hour, get 100 miles to the gallon, and be compact enough to pack up for easy transport. “He would be driving this little thing up and down the boardwalk getting up to 80,” Murphy told me. “Out here in October and November, there was nobody around!” Crime was high, and even buildings near the beach were run down or vacant. “Homeless people would go and piss on the door of a guy I knew, and he would run up to the roof, where he kept these rotten cartons of milk that he would pour on them,” Murphy recalled. “Everybody had their own way of interacting that was aggressive and interesting.” Some fled straight to Manhattan Beach after visiting in those years, but Murphy was energized by Venice’s distinct vibe and wanted to make its three square miles his home. Since pottery wasn’t likely to pay the bills, he changed careers: The son of an architect decided, despite lacking business experience, to become a local developer.

Several years ago, I met him on a sunny autumn morning at his office in the basement of a five-unit apartment complex on Venice Boulevard, a few blocks from the ocean. We walked together past a canal to the boardwalk. Looking north, he told stories about Venice’s oldest and tallest buildings––the ones that were built or permitted before the imposition of onerous height limits––and the impossibility of building anything today on the same scale. Then we walked south, taking note of single-family houses along the beach, including a diverting Frank Gehry design that struck him as too eccentric to win approval in today’s environment. “They’re appeasing a small group that has a vision of what Venice should be, which is more of a suburb by the sea,” he said. “Folks who see it as something different haven’t rallied and gotten organized.”

He offered to drive around and show me what he meant.

Murphy takes pride in having added to his neighborhood’s dwelling units, each of which offers more people access to its opportunities. Adding units might seem like a foregone conclusion for a developer. That’s the assumption of locals I sometimes overheard at Venice Beach’s Groundwork Coffee, who believed that greedy builders were making the area more crowded and dense, spoiling the bohemian community they loved. In truth, homeowners have successfully fought a years-long battle to make Venice less dense than it was before. And while they managed to stall population growth, they failed to preserve Venice’s culture. Limiting the neighborhood’s housing supply and the diversity of its built environment, in fact, gradually narrowed the sort of people able to live here. Venice was a working-class neighborhood in 1960. Owing largely to repressive land-use rules, its rents and median income rose much more sharply than those of L.A. as a whole. Venice is on course to be like Newport Beach by 2050, but less self-aware, with residents who purport to value diversity regulating it out of existence.

The hardship and misery the not-in-my-backyard impulse has inflicted on vast swaths of postwar Southern California trace their origins to 1964, when a man named Calvin Hamilton began his long tenure as L.A.’s planning director. At the time, his profession was grappling with critics like Jane Jacobs, whose The Death and Life of Great American Cities excoriated the hubristic urban-renewal projects of the 1950s for destroying whole neighborhoods, many of them populated by disenfranchised groups. As 1965 began, Hamilton embarked on an ambitious effort to gather feedback from 100,000 Angelenos (ultimately reaching a still-impressive 40,000) on how they wanted the city to evolve. The Watts riots of 1965 and continued unrest over the next three summers underscored that the Black residents of South L.A. needed to be heard. And the turmoil stoked the anxiety of white Angelenos, many of whom harbored the racial prejudices of their day and sought greater agency over “their” neighborhoods.

Come 1970, there was broad support for a portentous shift: Los Angeles would abandon the top-down planning that prevailed during a quarter century of postwar growth in favor of an ostensibly democratized approach. The city was divided into 35 community areas, each represented by a citizen advisory committee that would draw up a plan to guide its future. In theory, this would empower Angelenos from Brentwood to Boyle Heights to Watts.

In practice, it enabled what the Los Angeles land-use expert Greg Morrow calls “the homeowner revolution.” In his doctoral dissertation, he argued that a faction of wealthy, mostly white homeowners seized control of citizen advisory committees, especially on the Westside, to dominate land-use policy across the city. These homeowners contorted zoning rules in their neighborhoods to favor single-family houses, even though hardly more than a third of households in Los Angeles are owner-occupied, while nearly two-thirds are rented. By forming or joining nongovernmental homeowners’ associations that counted land-use rules as their biggest priority, these homeowners managed to wield disproportionate influence. Groups that favored more construction and lower rents, including Republicans in the L.A. Area Chamber of Commerce and Democrats in the Urban League, failed to grasp the stakes.

The Federation of Hillside and Canyon Associations, a coalition of about 50 homeowners’ groups, was one of the most powerful anti-growth forces in California, Morrow’s research showed. It began innocently in the 1950s, when residents living below newly developed hillsides sought stricter rules to prevent landslides. Morrow found little explicit evidence that these groups were motivated by racism, but even if all the members of this coalition had been willing to welcome neighbors of color in ensuing decades, their vehement opposition to the construction of denser housing and apartments served to keep their neighborhoods largely segregated. Many in the coalition had an earnestly held, quasi-romantic belief that a low-density city of single-family homes was the most wholesome, elevating environment and agreed that their preferred way of life was under threat. Conservatives worried that the government would destroy their neighborhoods with public-housing projects. Anti-capitalists railed against profit-driven developers. Environmentalists warned that only zero population growth would stave off mass starvation.

Much like the Reaganites who believed that “starving the beast” with tax cuts would shrink government, the anti-growth coalition embraced the theory that preventing the construction of housing would induce locals to have fewer kids and keep others from moving in. The initial wave of community plans, around 1970, “dramatically rolled back density,” Morrow wrote, “from a planned population of 10 million people down to roughly 4.1 million.” Overnight, the city of Los Angeles planned for a future with 6 million fewer residents. When Angelenos kept having children and outsiders kept moving into the city anyway, the housing deficit exploded and rents began their stratospheric rise.

The same basic pattern unfolded in Venice: First, people who loved the neighborhood bought homes there; then, some changed the rules to keep others out. In 1958, the official plan that guided growth in Venice allowed for a maximum of 91,293 people in the areas zoned for residential use. Over the years, it was revised repeatedly, with disproportionate input from homeowners. As of 2015, the plan for the same areas allowed for a maximum of only 44,513 people. Where developers could once have built an apartment complex, now they can build only a triplex or duplex. Lots that were once subdivided among four families are now occupied by one childless couple.

Those who’d like to move to Venice, buy a house, or pay less in rent each month might have been particularly frustrated on my tour with Murphy during our visit to two 8,000-square-foot lots a few blocks apart.

The first, 2207 Brenta Place, was developed in 1990 and holds an eight-apartment building. The one-bedroom units are a little over 800 square feet, and the three-bedroom units just over 1,300; rents range from $2,400 to $4,800 per month.

The other lot, 715–721 North Venice Boulevard, is on the corner of Oakwood Avenue. Construction on a four-unit building began in 2016 and was completed the following year. “I would have loved to put eight units there, too,” Murphy said. But even though the lot is on the corner of a main street, affects fewer neighbors, and is not far from Brenta Place, it faces much more restrictive zoning rules. Before 1980, Murphy explained, he could have built 16 units of housing on each of these properties. If he were starting the projects today, he might be able to put 10 units at Brenta Place, but just two on Venice Boulevard––20 fewer units, in total. And it’s not just the zoning rules. Aesthetic requirements, for things like varied rooflines, further limit the number of units on some parcels.

The North Venice Boulevard building might sell for $6 million: $2 million each for the three market-rate units, and the final unit set aside for a low-income family. “I’d rather have built eight units and sold them for a million dollars each, getting the price point down to something a much bigger group of people can afford,” Murphy said. “Or I’d have gladly given the city two low-income units if I could do eight total.”

Most anti-growth homeowners in well-to-do neighborhoods would be shocked by the damage they have done to their communities, their city, and their region. But their intransigence had this consequence: Rather than adding new housing units evenly across Los Angeles, or concentrating housing near transit or jobs, Morrow found, “density followed the path of least resistance.” Westside homeowners fought against growth. New housing was much easier to build in poorer, more heavily Latino neighborhoods, where anti-growth mobilization and resistance to construction were less pronounced, and even easier in enclaves of noncitizens, where neighborhood associations were unlikely to form.

Growth in those poorer neighborhoods served many of their residents well. Newcomers with large families needed relatively cheap housing and benefited from the informal networks and services that arise when immigrants cluster, as the Angeleno chef Roy Choi wrote in his account of the neighborhood that, around 1970, became known as “Koreatown.” Recent immigrants would gather to stake each other in ventures that would have been impossible without cheap commercial real estate. Choi wrote,

There had to be some trust in the group, or it was all for nothing. Every month everyone met and shared stories and dreams, and, in the course of all that, everyone decided on an amount. Then everyone anted up. Each month, one person got the jackpot and opened a business. A liquor store, dry cleaner, gas station, small restaurant, trophy shop, golf store … It was thanks to these … meetings that the ghost town came alive.

But the Westside’s approach to land-use policy hurt renters and people of color while exacerbating racial segregation. From 1970 to 2000, as L.A.’s Latino population increased from 18 percent to 47 percent, the Latino population of Brentwood, a tony Westside neighborhood, grew from 1.6 percent to 2.6 percent. The ostensibly pro-environment opponents of growth wound up fueling environmentally disastrous sprawl to the north and east. Traffic grew worse, even as multiple mass-transit projects were killed by slow-growth homeowners. With much of the city off-limits to newcomers, the most overwhelmed police precincts, fire stations, and emergency rooms seemed to get even busier.

Perhaps most consequentially, wealthy NIMBYs and the residential segregation they wrought pushed more students into the most overcrowded, under-performing schools. “L.A. finds itself in the strange position of having built 130 new schools for not a single new student in the system,” Morrow wrote, “because public schools in affluent areas are emptying out … while schools in poor areas are running over capacity, in part due to the underlying land use policy changes.” Throughout California, quality school districts drive nearby real-estate prices sky high, and homeowners who pay the premium are averse to allowing new apartments that would give more poor or non-English-speaking families access to what they consider “their” schools.

Gloria Romero, a former Democratic majority leader in the California State Senate, has a name for the relationship between California’s dysfunctional housing policy and an educational system that is ranked among the nation’s worst. “It’s zip-code education,” she told me. “If you’re rich you can go anywhere––a good public school, a private school––but if you’re poor you can’t afford to move to a district or a neighborhood with a good public school. You’re stuck. Those five digits fast-track too many kids to the prison system, or if they’re really lucky, into remedial college classes too many don’t pass.”

A recent Education Week ranking put California schools 23rd in the country. According to a 2017 study by GreatSchools, a national nonprofit, “African American and Hispanic students [in California] are 11 times less likely than white and Asian students to attend a school with strong results for their student group. Only 2% of African American students and 6% of Hispanic students attend a high performing and high opportunity school for their student group, compared with 59% of white and 73% of Asian students.”

While in the state legislature, Romero made education a top priority, sponsoring numerous reform bills, including a so-called parent-trigger law that allows parents at a failing public school to decide how it ought to be restructured. At times, she says, Democratic colleagues lambasted her for putting them in the awkward position of taking a vote in which public opinion was at odds with the California Teachers Association, which she calls the state’s fourth branch of government. “I believe in unions,” she told me. “But public education in California isn’t run with the best interest of the children in mind. It starts with adults—their salaries, pensions, and perks––and what gets left over is for kids.”

She has long called herself a pro-choice Democrat: She not only supports reproductive rights, but she’s also pro–public schools, pro–charter schools, pro-vouchers, pro whatever maximizes the options available to families in the state’s failing system. And after years of writing laws to try to reform schools, she decided to start and run her own organization, partnering with the charter-school leader Jason Watts on Scholarship Prep Charter School. (Romero has since left Scholarship Prep; she said that she had filed a gender and age bias claim against the company with the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing, and that it had been resolved. Scholarship Prep has not responded to The Atlantic's requests for comment. She has co-founded another network of charter schools, a model she continues to champion.)

Scholarship Prep opened its first campus in Santa Ana in 2016, and The Wall Street Journal reported that “about 90% of its 300-some students qualify for a free or reduced-price lunch” and “most parents walk their kids to school because they don’t own cars.”

I met with Romero at a sister campus in Oceanside, a racially and economically mixed city at the edge of Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, in North San Diego County. As at the Santa Ana campus, Scholarship Prep Oceanside runs from kindergarten through eighth grade and emphasizes academic rigor and extracurricular activities, like athletics, music, and dance, that help students from working-class backgrounds secure as many college scholarships as possible. Out front is a “walk of honor,” a path flanked by flags from different colleges, chosen not only for their academic rigor but also for their rate of success at graduating scholarship students. “At Cal State L.A., I taught kids who had done everything right,” Romero explained. “They took the high-school exit exam, were the first in their family to go to college. But as soon as I assigned them a report, I thought, They can’t write! They need remedial classes that won’t count toward their degree. Kids would take seven years to do their B.A., trying to undo 12 years of negligence in public schools, and their scholarships would run out.”

At Scholarship Prep, each classroom is named after a university, such as “Room Notre Dame,” where that school’s colors, blue and gold, are everywhere. Over the course of the year, students learn where their particular college is on a map of the country, sing its fight song, follow its sports teams, and talk about its history. The next year, they’ll familiarize themselves with another school; then another the following year. By high school, rather than panic when it’s time to take the PSAT, or regret the bad grades of their sophomore year when they apply to the University of California at San Diego, they’ll have been thinking about where and how to go to college on scholarship for most of their lives. Their parents will have absorbed the nine-year acculturation, too.

“Parents seek us out to escape a system where wealth, reflected in housing values, determines the education your kids get,” Romero said. She believes charter schools to be “like the Statue of Liberty: Give us those who yearn for education. I call them refugees from the public-education system. We can’t wait to change how housing works. These kids are growing up. They need good schools now!”

To underscore the urgency, she grabbed a parent who happened by while we were talking. Jackie Howe was eight when her family fled Vietnam during the exodus of refugees after the war. They were resettled on the eastern edge of Los Angeles County. She remembers the Mendoza Elementary School in Pomona for its poor quality. “We came here with nothing,” she told me. “Education is vital to our survival. But I’ve noticed that all these years later, choices are still very limited for immigrant children like mine. I worked with the district. My friends and I volunteered and donated money. But we didn’t see the quality that should be available to our kids.” That’s how she found herself supporting Romero in trying to expand Scholarship Prep to Oceanside. As Howe remembers it, there was opposition from some local officials. “We were shocked,” she said. “They said that this is too high rigor for kids in this community. I thought, What does that say about your dreams for these kids?”

“I was told we were being ‘too aspirational,’” Romero said. “Can you imagine?”

Every blue state has red counties. In California, to drive Highway 99, which runs north from Bakersfield through the Central Valley, is to tour one of the world’s most productive agricultural regions. Highway 99 also links many of the communities in this blue state that go reliably red in presidential elections; send federal representatives like Republican Kevin McCarthy, the House minority leader, to Congress; and supply Sacramento with its waning supply of Republican state legislators.

In Berkeley to Bakersfield, the concept album by the country-rock band Cracker, the frontman David Lowery evokes a California that he sees as a microcosm of America. His songs unfold like a road trip that passes through the radical-left activism of the East Bay before slowly turning inland into what he described to me as “a personal sort of right-libertarian sentiment.” This is achieved through characters, like the eponymous “California Country Boy,” who says, “Ain’t no palm trees where I come from,” no waves, gridlocked traffic, or movie stars. His Central Valley home is oil fields and endless farms. “I’ve got good friends out in Texas. And I got family in Tennessee,” he sings. “But this here country boy’s from California. Ain’t no place I’d rather be.”

On a tour of the region to better understand its economy, and why so many locals feel that politicians in Sacramento and elites on the coast don’t understand what they do well enough to regulate it fairly and sensibly, I met Larry Starrh, a jovial former college theater professor who returned to his hometown of Shafter to be a third-generation farmer. He had about 4,000 acres of almonds and 1,500 acres of pistachios planted, more land lying fallow for lack of water to irrigate it, and a bygone grove of almond trees that had been bulldozed and left in a field to rot, a casualty of a recent drought.

Earlier that week, he told me, an FM radio station had asked him to pose a trivia question on the air—the station was going to give away concert tickets to the first caller to get the answer right. Starrh asked how many pounds of almonds were forecast to be produced in California that year. “So people are calling in,” he said, “and the first guess was 25,000 pounds. Well, that’s not even close! I was amazed how long it took to get someone up to 100 million pounds. The right answer is 2.2 billion pounds of almonds. That’s how far away people are from understanding what happens in the state agriculturally.”

The first time I met Assemblyman Vince Fong, a 41-year-old native of Bakersfield, he explained to me that many of his constituents feel that their interests and concerns are not well understood in the state capital, in part because legislators coming from San Francisco, Santa Barbara, or Westwood don’t know much about their way of life.

“Portions of the state aren’t familiar with growing food or producing power,” he said. “These are the mainstay industries that feed and power not only our state but our entire country. It’s not just the farmers and oil workers, it’s families that buy the food and pump the gas, products many take for granted. We expect them to be at the grocery store or the gas station, but people have to produce those things. These are the perspectives that shape my decisions and that should shape policy. When the state regulates in flawed ways, hardworking families suffer.”

In Sacramento, the first bill he introduced sought to force state bureaucrats to go back to the legislature before imposing any regulation that triggered cumulative costs of more than $50 million. “If an agency is going to impose these costs, we should approve or disapprove,” he said. “We’re the accountable body. The people in our community loan us the power every two years to be their voice. They didn’t loan that power to an unelected person at an agency.”

Fong isn’t simply regurgitating conservative boilerplate when he says that California’s regulatory apparatus needs reform. In 2017, the Institute for Justice, a public-interest law firm, released a report on barriers to work that disproportionately affect the middle and working classes. “California is the most broadly and onerously licensed state,” the report found, and is also “the worst licensing environment for workers in lower-income occupations.” The state government licensed 76 of the 102 lower-income occupations studied, surpassing all but two other states, while imposing “high average fees ($486), lengthy average education and experience requirements (827 days lost), and a high average number of licensing exams (about two).”

At the other extreme of the business hierarchy, a survey of 383 CEOs by Chief Executive magazine, which weighed regulations and tax policy above all other metrics, ranked California the worst state for business, and Forbes ranked it among the worst for its high business costs and stifling regulatory environment. California’s workers’ compensation premiums are among the costliest in the nation. In its survey of corporate attorneys assessing the fairness and reasonableness of state liability systems, the Institute for Legal Reform, an affiliate of the Chamber of Commerce, ranked California 48th.

The state’s landmark environmental law, the California Environmental Quality Act, is so vulnerable to abuse that it has repeatedly prevented the addition of bike lanes. “Los Angeles, Oakland, San Diego and San Francisco have faced lawsuits, years of delay and abandoned projects because the environmental law’s restrictions often require costly traffic studies, lengthy public hearings and major road reconfigurations before bike lanes are installed,” the Los Angeles Times reported. “Bicycle advocates say the law has blocked hundreds of miles of potential bike lanes across the state.”

In Fong’s telling, the inability to reform even the most dysfunctional laws hurts working-class people across the state. When I asked what particular regulations were upsetting his constituents, I wondered if they were all thorny instances of competing goods, as with water needed for an endangered fish, the delta smelt, and a hugely productive farming region, or the trade-off between air quality and the ability of farmers to burn waste.

Some of them could be characterized that way. Take Randy and Kyle Griffith, a father-and-son team who run Randy’s Trucking. Randy started the business in 1975. “I just couldn’t work for the other guy,” he told me. “I bought one tractor, one trailer, and started from there.” By reinvesting what he earned in the business, he grew his fleet over time, sold much of it off during a recession, then rebuilt again, until 2011, when he employed about 150 people and sent out 60 or 70 trucks a day, mostly on local jobs. Then the California Air Resources Board passed a rule intended to reduce particulate matter emitted by diesel trucks and buses—a rule that would require him to either replace half of his fleet or retrofit trucks built in the late 1990s with filters that cost between $15,000 and $20,000 each.

The sum would be staggering to almost any small business. “With our cash flow and the work that we were chasing during the downturn,” Kyle Griffith said, “it would have been impossible.” They tried and failed to meet the deadline. Then they got a letter imposing a $1 million fine, which would have put them out of business. With Fong’s help, they were able to negotiate the fine down to $250,000, money they wanted to spend on new trucks or filters instead, though Randy insisted that the filters don’t make sense for his business.

“An over-the-road driver picks up a load from Shafter out at the Target plant and hauls it to Nebraska or whatever,” Kyle said. “A filter on that truck is running at a high temperature.” But most of the jobs for Randy’s Trucking are short hauls. “A typical driver for us might leave our yard at 6 a.m., drive 25 minutes, and park at an oil field. The driving portion is done. But his truck is idling, not on a clean road, but in dirt, dust, mud, the whole thing. So it’s intaking all that nasty stuff into this filter, which is trying to burn it off and can’t––the filters are not designed for that situation, which our trucks are in for 12 hours a day.”

Patrick Wade is in a very different business, but it’s also a niche within a larger industry. There are pharmacies like CVS or Walgreens, and then there are compounding pharmacies, which buy raw ingredients and make everything they sell. Precision Pharmacy, Wade’s company, compounds drugs for pets, horses, and wildlife, and never for food-producing animals or people. But like any CVS in Bakersfield, Precision Pharmacy is regulated by the California State Board of Pharmacy, a body made up of political appointees, only some of whom have industry experience. Sometimes the burdens are comical. “Imagine having to get a ‘patient name’ for a horse only identified by a number,” Wade says, “or having to list the birthday for the owner of a herd of deer.” At other times, the regulations impose bigger costs.

For example, California requires its compounding pharmacies to do a test required in no other state on many of the formulas it produces. And it’s so expensive that it renders seldom-used formulas uneconomical. Wade told me he doesn’t lose that much in profit by ceasing to offer them. “But some of these formulas, like a specialty vitamin supplement for horses, we were the only pharmacy in the country that made it,” he explained. “We have to tell people, we don’t make that anymore, because not enough people would buy it at 10 times the cost, and that’s what I’d have to charge to recover the cost of the test they force on us.” In Wade’s experience, whatever benefits the regulation offers his customers are negligible—and far outweighed by the costs.

In 2014, Precision Pharmacy settled a set of allegations brought by the State Board of Pharmacy by paying a $10,000 fine and entering into a three-year period of probation, which has since concluded. That experience might have colored Wade’s view of regulation, but in his telling, his primary concern is that the board, or another regulatory body, will impose a new rule or interpret an old rule in a novel way. He feels that for reasons he doesn’t understand, California is antagonistic to anyone who makes anything. “It’s funny, people in the interior of California have been complaining about overregulation for quite a while,” he said. “And now a hot topic is that a lot of top tech companies in Silicon Valley absolutely thrived in an environment of virtually no regulation. The California economy is divided between this industry that has totally transformed our lives with no regulation––maybe there’s not been enough, and that’s coming from someone who leans libertarian––and then you have people who physically make things in the rest of the state, and it’s really tough. We just need some cooperation and predictability.”

Starrh, the almond farmer, had a similar complaint. “There’s an aspect of farming that you just love to be out there doing,” he said. “It is a lifestyle. And it used to be that I could just go out to the ranch and farm––start making decisions and playing in the dirt. Now you spend your time dealing with meetings on regulations. At times I just want to retire.” I suggested that the one-time college theater teacher might return to the stage. But it turned out that he had encountered similar frustrations on that front, too. A few years back, his family of drama geeks bought an old Ford dealership in order to turn it into a community theater. “We felt culture crosses barriers,” he said. “If we could have a place where different people could come together and enjoy good, redeeming stuff that everybody could participate in, we’d see we’re not that different.”

He hadn’t anticipated too much difficulty building it. “Shafter is a small town, these guys wanted it, they knew what we were doing. I know the city manager. He’s a good friend. I know all the city-council members really well. I’m thinking we’ll get this done fast, it won’t cost me an arm and a leg.” He estimated that their building was big enough to fit 1,000 people in it, but early on, he was advised that he shouldn’t exceed 300 people, or he would be subject to more costly building standards. “So I told the inspector we’d build the theater for 300 people,” he said. “We ordered 300 of these really expensive theater seats that roll back. They’re being built in England. Six months or a year later, we finally have the seats. Then the inspector comes back and says, ‘Well, if you’re putting 300 seats and there’s a 60-piece orchestra, you’ve got more than 300 people. You’ve got to have that re-engineered.’” Instead, Starrh decided to put some of the pricey seats in storage. Fewer people are able to attend performances as a result. He says he doesn’t think anyone is any safer for it.

Joni Mitchell once wrote a kind of postcard to California that remains among the best attempts to capture its promise. She sang that she was sitting in a park in Paris, reflecting on her travels in Europe. “Still a lot of lands to see,” she sang, “but I wouldn’t want to stay here. It’s too old and cold and settled in its ways here. Oh, but California!” She longed for its dynamism. In California, anyone could look to the future––and feel confident that they had a place in it. “Will you take me as I am?” she sang. “I’m coming home.”

California is closer than it has ever been to achieving part of its dream, allowing people of all races and nationalities to seek a golden future. But older Californians, liberal and conservative alike, are too indifferent to the needs of the next generation, too settled in their ways to accommodate them. The Democrats who run the state fail all but its most fortunate residents in the realms of housing, education, and economic opportunity. And no opposition is correcting for the worst shortcomings of the Democrats, because despite the efforts of some tolerant and farsighted GOP legislators, like Fong, much of the California GOP flunks the inclusion-threshold test voters now demand, most recently by tying its fortunes to Trumpism even as the state’s voters overwhelmingly rejected it.

The NIMBY impulse is not new. Carey McWilliams observed in 1949 that although Californians were fascinated by their state’s phenomenal growth, they were simultaneously “disturbed and even repelled” by it. “They want the state to grow, and yet they don’t want it to grow,” he explained. “They like the idea of growth and expansion, but withdraw from the practical implications.” But when he wrote those words, amid a severe housing shortage, policy makers in both parties still encouraged countless small developers to build houses and apartments as rapidly as possible.

Today matters are much worse. The most powerful factions of residents do not want their state to grow and do not accept the fact that it surely will. For 40 years, they haven’t just failed to adequately plan for the housing needs of California’s current population; upper-income residents in San Diego and the Bay Area as surely as those in Los Angeles have deliberately fought to restrict the supply of housing. Even now, when housing costs are the primary reason that a majority of registered voters say they’ve considered moving, and when politicians in both parties pay lip service to the problem, there is insufficient political will to attempt a plausible solution. And the forces paralyzing the state are all the more entrenched because some of them believe themselves to be protecting the California Dream.

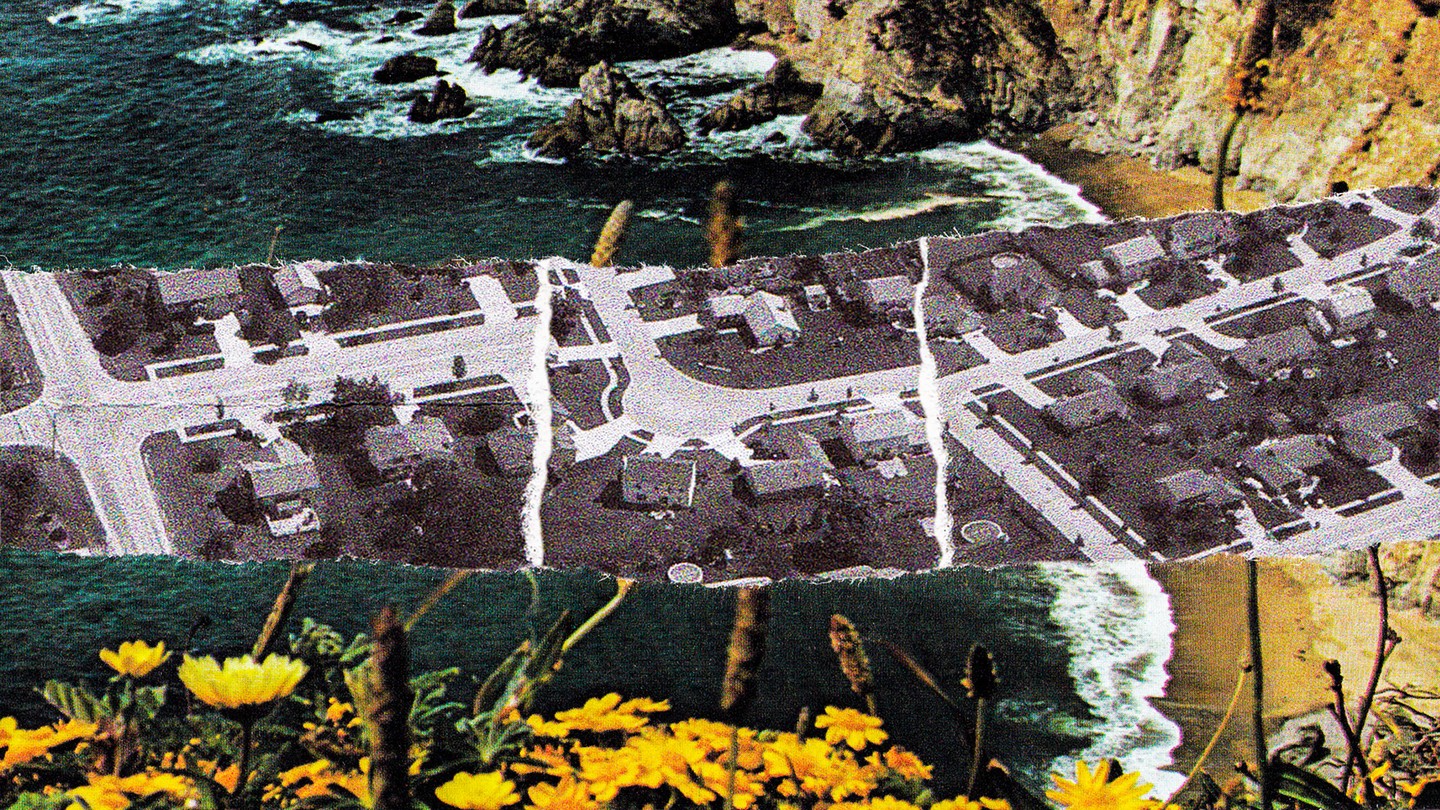

I feel the pull of their backward-looking vision. Years ago, I spent two glorious seasons in the Sea Ranch, a 10-mile stretch on the rugged coast of Sonoma County where beaches strewn with mussels rise to majestic bluffs; then to meadows where deer frolic and sleep; and, just beyond, hills of redwood forest that thrive in the fogs that roll in many evenings. If 50 million people could sustainably inhabit a state where all coastal development resembled the Sea Ranch, I’d sign up. In that fantasy, San Franciscans would all live in detached Victorians and Angelenos would all reside in prewar bungalows. Central Valley farmers could use all the water they wanted on their crops without affecting commercial fishermen, who could catch all of the fish they wanted forever. There would be no lines at Disneyland.

Those expectations, fantastical as they sound today, seemed plausible within living memory. The Inexhaustible Sea was published in 1954. Around 1970, the Sea Ranch was considered a model of sustainable development. On rainy winter days in my 1980s youth, there actually were no lines at Disneyland. I once went on Space Mountain 18 times in a row, finding no one in line each time the roller coaster ended. Imagine if, in middle age, I felt entitled to pass laws so I could keep doing that into my 70s and 80s, no matter how many kids never got a turn. That is the anti-growth Californian, mistaking nostalgia for justice.

California must now turn away from the wishful thinking of preservationists and toward the future it could enjoy. Success will not mean perfection, nor an end to hardship or challenges. But it will have been achieved if a chronicler at California’s bicentennial can approvingly quote the summation of the Golden State that McWilliams offered to mark its centennial:

This, then, is California in 1948, a century after the gold rush: still growing rapidly, still the pace-setter, falling all over itself, stumbling pell-mell to greatness without knowing the way, bursting at its every seam … California is not another American state: it is a revolution within the states.

The rising generation’s charge, whether on behalf of the country, the blue-state model, or the tens of millions who’ll make their home in the state, is to make California exceptional again.

Correspondence about all matters California are encouraged. Email conor@theatlantic.com with your reactions, observations, story tips, or recommendations.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.