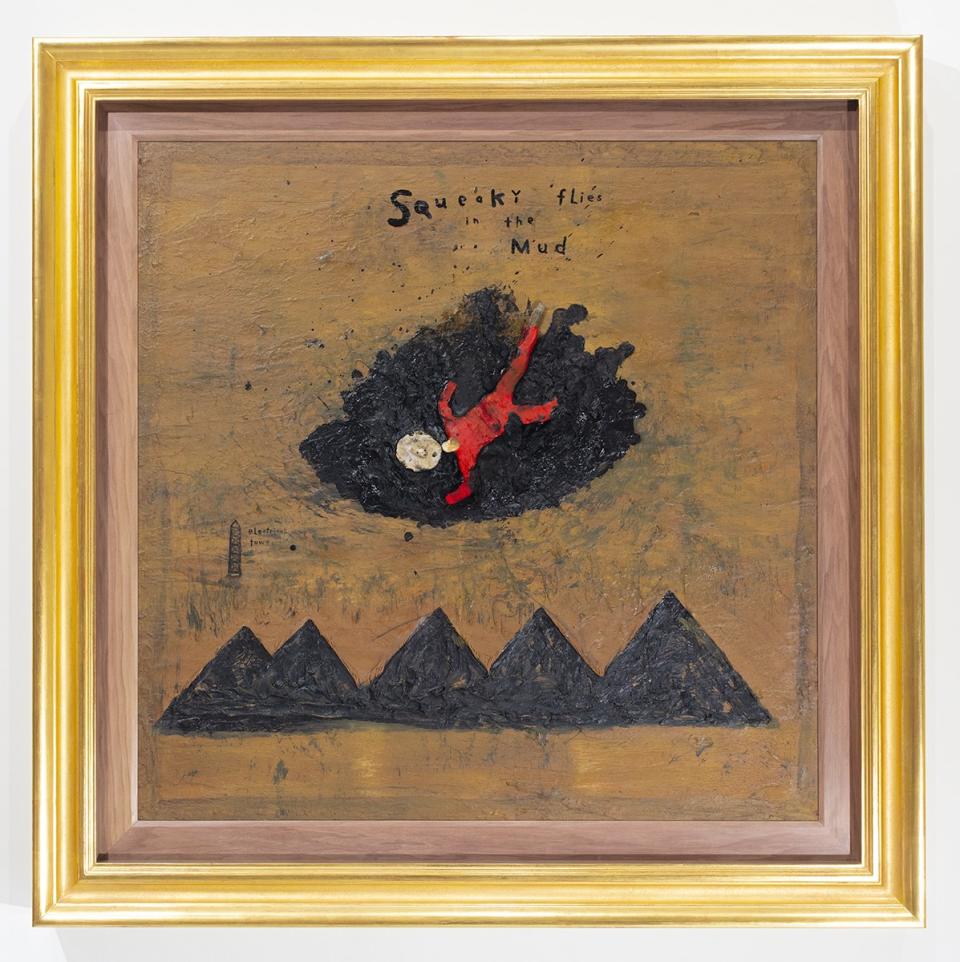

The Expanded Consciousness of David Lynch’s Squeaky Flies in the Mud

David Lynch loves the word ointment.

It’s a term that makes many cringe, appearing on word-aversion lists and inviting exaggerated pronunciation to indicate just how off-putting the word feels on the tongue.

But Lynch, the artist and master director behind such macabre, Surrealist films as Mulholland Drive, The Elephant Man, and Blue Velvet—not to mention the cult favorite television series Twin Peaks—has made a career out of leaning into the world’s discomfort, or at least of exposing it.

He tells me of his affection for the maligned term in the library atop Sperone Westwater, the New York gallery that is home to a new show of Lynch’s paintings, watercolors, works on paper, sculptures, and furniture. Called Squeaky Flies in the Mud, the provocative, cross-disciplinary show, which runs through December 21, is Lynch’s first solo art exhibit in New York since his 2012 show at Tilton Gallery.

Ointment is the title and subject of one of the show’s mixed-media paintings. In it, a painted human figure with a swirling black cloud for a head holds an actual, 3D tube in its hands as the word ointment, written in Lynch’s sparse, scratched lettering, spurts out underneath. More than just the word, Lynch loves the tube itself: its simplicity, its coloring, its functionality. “Just the right amount of silver in the middle of that painting. Very nice to have that,” he says, his white shock of hair glinting from across the table.

It’s exactly this juxtaposition of the offbeat and the everyday—what’s more ordinary than a tube of ointment?—that has come to define Lynch’s work. Though he is undoubtedly better known for his contributions to film (just last month he received an honorary Academy Award for lifetime achievement), he calls painting his first love. He has shown his visual artwork at New York’s Leo Castelli Gallery, in 1989, and at galleries in France, Spain, the U.K., and Japan. His first major museum show in the U.S. opened in 2014, at his alma mater, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art (PAFA).

But, arguably, it was not until last year’s retrospective at the Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht that Lynch’s fine art practice gained wider recognition. The Bonnefanten show featured more than 500 works by the prolific Lynch, in such varied mediums as paintings, sculpture, lithographs, and photography. While several pieces in Squeaky Flies in the Mud appeared in earlier shows, much of the work on display at Sperone Westwater is new, fresh out of his Los Angeles studio.

“I think this is a real opportunity for us certainly, and also for David, to really make more broadly known the fluidity of his output and the fact that [his work] is really transdisciplinary,” says Angela Westwater, the cofounder of Sperone Westwater.

She thinks fans of Lynch’s films will recognize some crossover in his fine art work: the creation of worlds and characters, the sensitivity to organic phenomena, the opposing forces of light and dark, the quirkiness. “It’s gray and murky and it’s a cloudy kind of reality, but it’s one that, in many respects, I think also reflects humor,” says Westwater. “And I think there’s ultimately a kind of empathy in his work, particularly in the art from the studio.”

David Lynch Squeaky Flies Installation View.jpg

David Lynch was born in Missoula, Montana, in 1946. Though transient due to his father’s job as a research scientist with the United States Forest Service, his childhood was a happy, loving one. He showed interest in art from an early age. His mother never gave him coloring books, thinking them too restrictive for his creative mind.

As Lynch recalls in the 2016 documentary David Lynch: The Art Life, a darker side emerged after the family moved to Virginia when he was a teenager. Lynch started partying, neglecting his schoolwork, having “dark, fantastic dreams”—a theme that would greatly influence both his art and filmmaking. What saved him was reconnecting with his love of painting. He spent hours each day putting brush to canvas at the studio of the artist Bushnell Keeler, a friend’s father. “That...realization, that you could be a painter...blew all the wiring. And that’s what I wanted to do, from that second,” Lynch says in The Art Life.

He attended art school at PAFA, in Philadelphia, where he explored painting, sculpture, sound, film, and installation. In addition to the school, the city itself had a huge impact on him. In contrast to his idyllic childhood throughout the heartland, Lynch’s early adulthood in Philadelphia exposed him to the grittier sides of human existence, which he found creatively inspiring. “There was thick, thick fear in the air. There was a feeling of sickness, corruption, of racial hatred. But Philadelphia was just perfect to spark things,” he says in the documentary.

Lynch started experimenting with short films and, in 1977, made his feature-film debut with the haunting Eraserhead. More films—and then fame—followed. Lynch’s best-known work is likely Twin Peaks, the surreal crime drama he co-created with Mark Frost, which aired from 1990 to 1991. Despite its cancellation after two seasons, the series found a cult following in the years after, and a third season, Twin Peaks: The Return, ran on Showtime in 2017. Mulholland Drive, his acclaimed 2001 neo-noir mystery, nabbed Lynch his third Oscar nomination for best director.

But all the while, there was his other art, his first love. “I miss painting when I’m not painting,” Lynch wrote in his 2018 memoir, Room to Dream. Heavily inspired by Francis Bacon, Lynch is drawn toward thick paints and various knickknacks, fabric, wires, and living (or rather, once living) things, which he affixes to his canvas. His work feels tactile, dimensional, palpable. You want to touch it—but you’re also afraid to.

The show at Sperone Westwater highlights this texture, pairing his large-scale mixed media with smaller watercolors and anthropomorphic lamp sculptures (which do indeed work). These are not pieces one can give a passing glance before moving on. Just as his films feel like their own universe, so too does his art work. There’s a whole story going on in each piece—“I call them small stories,” Lynch says back at the gallery. “To me, it’s a whole kind of world going on in the things.”

Depending on your interpretation, those worlds can feel creepy, hopeless, even violent. Take Billy (and His Friends) Did Find Sally in the Tree (2019). The work seems to show Billy, a character who appears in other Lynch paintings, carrying a knife as he approaches a tree where a girl, presumably Sally, hangs from a branch. The exhibition’s eponymous painting, Squeaky Flies in the Mud (2019), finds a red-clad character stuck in a thick, dark glop suspended over jagged peaks—which, pick your metaphor. Lynch rarely if ever explains his work, leaving his audience to extrapolate what they will.

“Certainly they’re foreboding,” says Westwater of the works in the show. “Something’s happening, and we’re not sure it’s good. It’s puzzling, it’s mysterious, it’s thought-provoking.”

But the work is also fun. There’s a wink in, for example, the title of Ricky Finds Out He Has Shit for Brains (2017), or the balloon-like Mickey Mouse head in Billy Sings the Tune for the Death Row Shuffle (2018)—we’re just not always sure who’s winking at whom. Part of the levity comes from Lynch himself. In person, he couldn’t be more different from the dark worlds he creates. He is warm, gracious, disarming, and says things like “super duper” and “good deal” in an earnest, middle-American twang.

Perhaps his demeanor is, at least in part, thanks to Lynch’s other passion: Transcendental Meditation. Lynch has spoken often about its wide-ranging benefits, and his foundation’s mission is to spread the practice in order to prevent and eliminate stress and trauma among at-risk populations.

“Meditation, throughout the long corridor of time, was to experience the treasury within each one of us human beings,” Lynch tells me—a way of tapping into our highest potential, of finding the creativity, intellect, curiosity, and pure goodness buried in our souls.

With a dedicated meditation practice, Lynch says, “You feel like life is more like a game than a torment. And when you start expanding these positive qualities, the side effect is negativity starts to lift away. So people who are transcending every day, they see stress, traumatic stress, anxieties, tension, sadness, depression, all this family of negativity, hate, anger, and fear, start to—automatically, without trying—evaporate.”

Maybe it’s this expanded consciousness that helps us square the “super duper” with the super dark. Lynch sees that one doesn’t exist without the other. The world is both: sharp edges and soft clouds. Sunny Missoula and gritty Philadelphia. But we can channel the good, beat back the bad, and open ourselves up to the boundless expanse.

Originally Appeared on Vogue