The Enigma of the Man Behind the $110 Million Painting

Thirty years after his death, Jean-Michel Basquiat defies easy categories. Was he an artist, an art star, or just a celebrity?

In May 2016, a painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat sold for $57.3 million. One year later, another painting of his from 1982, Untitled, sold for $110.5 million, making it the sixth-most-expensive work of art ever purchased at auction, and setting a record for an American artist. Basquiat is not the first painter to have a canvas sell for a price that strikes ordinary people as obscene. But when Jeffrey Deitch, a prominent curator and dealer, said after the sale, “He’s now in the same league as Francis Bacon and Pablo Picasso,” it was hard to pin down the precise meaning of the word league. Was Basquiat now considered as great an artist as Picasso? Or was he merely as expensive to own?

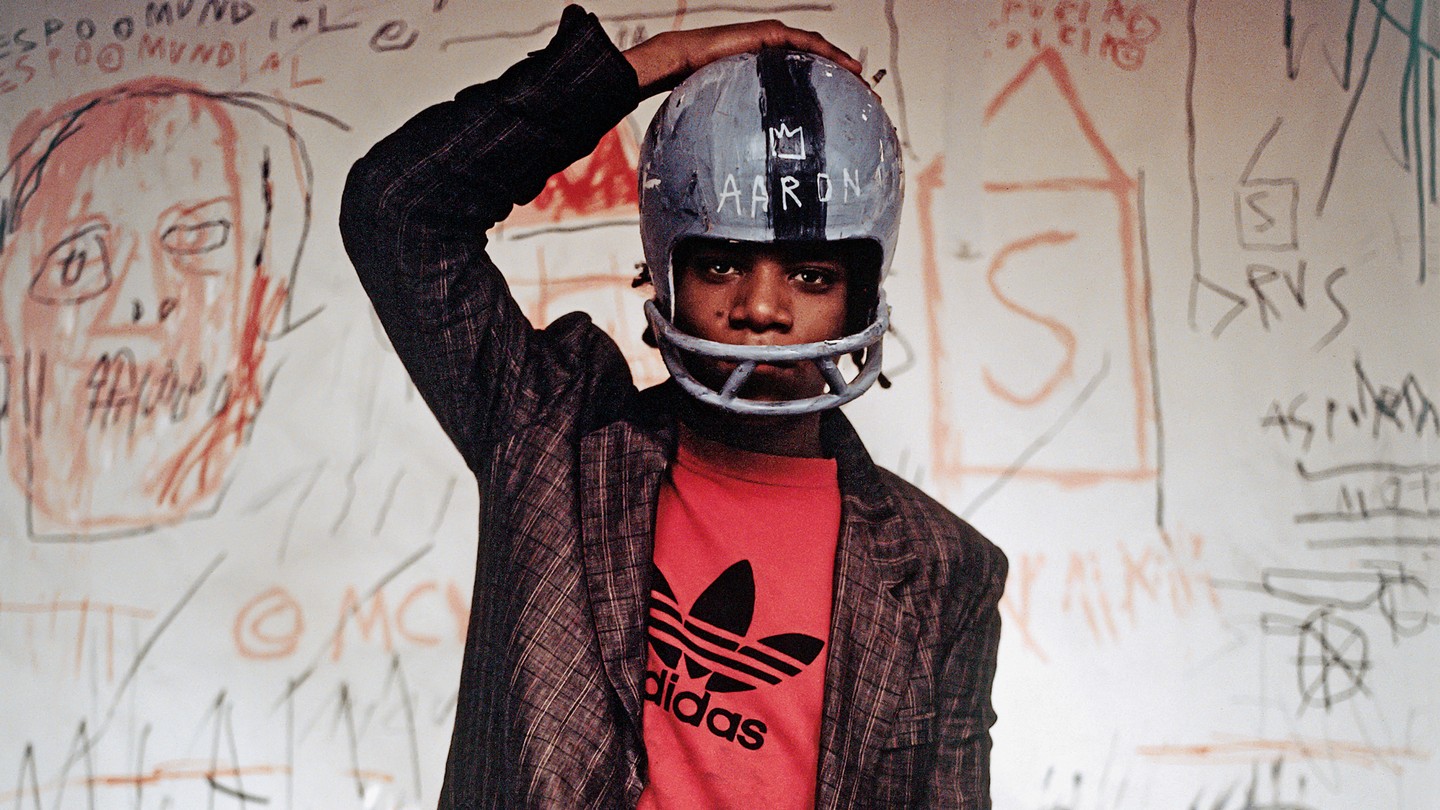

Basquiat became famous in the early 1980s, when the idea that artists were supposed to be commercial innocents fell apart for good, and when the idea of the “art star”—a funnily abbreviated inversion, if you think about it, of starving artist—first came into vogue. In 1985, The New York Times Magazine ran a cover story on Basquiat, titled “New Art, New Money.” Its tone was both awed and suspicious, with constant references to a hot, possibly gullible, market in contemporary art. His work was said to be selling “at a brisk pace—so brisk, some observers joked, that the paint was barely dry,” and Basquiat himself was quoted as worrying he had become a “gallery mascot.” Whatever else was true, as the art historian Jordana Moore Saggese has said since, “this was not the starving artist the public was accustomed to seeing.”

In the 30 years since Basquiat died of a drug overdose, in 1988, at the age of 27, the prices of his work have climbed steadily upward, taking some astonishing leaps along the way. Everyone remains fascinated by him—the life is compelling, the person bewitching, the canvases impossible to turn away from—but nobody agrees on why. His work seems to elicit one of two reactions from people. The first, as the writer bell hooks noticed when she attended a 1992 retrospective of his work at the Whitney Museum, in New York, is avoidance:

I wandered through the crowd talking to the folks about the art. I had just one question. It was about emotional responses to the work. I asked, what did people feel looking at Basquiat’s paintings? No one I talked with answered the question. They went off on tangents, said what they liked about him, recalled meetings, generally talked about the show, but something seemed to stand in the way, preventing them from spontaneously articulating feelings the work evoked.

Standing before Jeff Koons’s Balloon Dog, you take a selfie. Before Untitled, which its owner is now exhibiting on a global tour, you … do what, exactly? A common initial response—that the art is slapdash, tender, true—feels wrong somehow, as if we haven’t gotten it. Unwilling to play the part of the rearguard philistine anymore, we stay quiet, stranded in a vaguely shameful silence. In front of the painting, we fear we have seen or felt too little, especially given the $110.5 million price tag.

Basquiat’s works can also elicit the opposite response, very much in evidence in commentary on a recent retrospective mounted at the Barbican, in London, and then at the Schirn Kunsthalle, in Frankfurt. Anxious to stake a claim for the paintings’ place in art history, critics load them up with extra signification. I’ve seen the following cited as influences on, or analogies to, Basquiat’s work: action painting, art brut, surrealist automatism, William Burroughs’s cut-ups, the schizoanalysis of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Leonardo da Vinci, punk, postpunk, no wave, hip-hop, bebop, Lee “Scratch” Perry, Einstein on the Beach, Herman Melville, and Jack Kerouac. The convergence of multiple lines of influence is apparent in Basquiat’s work, and has been called a form of “creolization,” and fair enough. But there’s creole, and then there’s the kitchen sink. If all of his creations were lost, and you had to reconstruct them going only on the criticism, you would end up with some abominable artwork.

What critics seem to be striving for on behalf of Basquiat isn’t understanding but respectability, which anyone looking at the paintings can immediately see Basquiat was uninterested in. These canvases were made by a young man, barely out of his teens, who never lost a teenager’s contempt for respectability. Trying to assert art-historical importance on the paintings’ behalf, a critic comes up against their obvious lack of self-importance. Next to their louche irreverence, the language surrounding them has felt clumsy and overwrought from the beginning. What little we know for sure about Basquiat can be said simply: An extraordinary painterly sensitivity expressed itself in the person of a young black male, the locus of terror and misgiving in a racist society. That, and rich people love to collect his work. We have had a hard time making these two go together easily. But so did he.

For many years, the photos accompanying the Times piece supplied the public with its image of the artist. Basquiat is dressed in an Armani suit, barefoot, dreadlocked, paint-spattered. He looks—it’s hard to tell, he stares so blankly into the camera. With the benefit of hindsight and some good reporting, we now know that Basquiat was being crushed under money and publicity. At the very same time, he was being asked to reinvest painting with its foregone aura of authenticity, even saintliness, because he was black. No human being could have survived that, and he didn’t. The irony of his work’s ever-rising prices is that, far from clarifying his stature, they keep alive the question he repeatedly asked himself: Am I an artist, an art star, or just another celebrity?

Basquiat’s mother, Matilde, was a Brooklynite of Puerto Rican descent. In some accounts she is a loving and nurturing figure, taking him to the Museum of Modern Art to see Picasso’s Guernica and to the theater to see West Side Story, giving him a copy of Gray’s Anatomy. (All of these appear as touchstones in his work.) In other accounts she is erratic, beating him for wearing his underwear backwards, threatening to kill her entire family with a jerk of the steering wheel. Basquiat once said his mother carried “a worry line on her forehead from worrying too much.” He called her a bruja, a “sorceress.” She was in and out of mental hospitals. He told one interviewer: “She went crazy as a result of a bad marriage.”

His father, Gerard, was a Haitian immigrant. He was upwardly mobile, middle class, and professional, and he wanted to instill middle-class values in his oldest child. His oldest child wanted none of it. Gerard Basquiat reportedly once beat his son so severely that Jean-Michel went to school the next day walking with a cane. (Gerard has denied this.) Other times, the story goes, he was so badly beaten that he called the police. His parents separated permanently when he was 7, and his father later moved him and his two younger sisters from East Flatbush to a townhouse in Boerum Hill. Gerard, who always insisted that the Basquiats had been an elite family in Haiti, obtained a night-school degree in accounting and eventually became the comptroller for the Macmillan publishing company.

In their new neighborhood, Gerard played the happy divorcé, in a blue blazer with brass buttons, driving a Mercedes-Benz. Jean-Michel disappeared into the crawl space beneath the staircase, covering it in his drawings. What art Basquiat made, and how he made it, remained closely bound up in his own unsettled relationship to real estate. He ran away at least twice before leaving home for good at 17. That meant—and here something of a mythical fog descends—living in Washington Square Park and fleabag hotels, and rotating through the sofas and beds of various friends and lovers.

He began his life as an artist spray-painting tantalizing koans on the walls in and around SoHo under the pseudonym Samo, short for “same old shit.” His work as Samo was a collaborative project with a friend, born of an impulse universal among teenage boys. As 17-year-old “Jean” explained to The Village Voice, Samo was designed as “a tool for mocking bogusness.” He kvelled at how the SoHo types had fallen for it. “They’re doing exactly what we thought they’d do,” he told the reporter. “We tried to make it sound profound and they think it actually is!” It’s hard, reading the piece now, not to hear him talking back to the blue blazer:

This city is crawling with uptight, middle-class pseudos trying to look like the money they don’t have. Status symbols. It cracks me up. It’s like they’re walking around with price tags stapled to their heads. People should live more spiritually, man. But we can’t stand on the sidewalk all day screaming at people to clean up their acts, so we write on walls.

In 1979, he gained “his first stable home,” says Alexis Adler, his roommate from the time, “the first place he had a key to.” He was 18; she was 22. In their sixth-floor walk-up, Basquiat began to make the transition from street tagger to gallery artist. “He wrote and drew on any surface,” Adler recalled in Basquiat Before Basquiat, a slim volume that accompanied the first public exhibition, in 2017, of the surviving materials from that East 12th Street squat. His terrain included “the walls and floor of the apartment and the building’s hallways, which were strewn with discarded appliances.” Their apartment is described as a heavenly cocoon, overlooking the “shooting galleries,” the drug dens of Avenue B. They went dancing every night. “Art was life and life was art,” Adler wrote.

A new documentary, Boom For Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat, made with the cooperation of Adler, expands on a now-familiar story. “One week ago New York City tottered on the brink of financial default,” President Gerald Ford intones over the opening montage of a busted-up and burning city. During this period, we’re told, a tiny subset of young people, fleeing boring lives elsewhere, gravitated to the lawlessness and decay and created their own urban village. The streets may have been dangerous, but that encouraged a sociable and intimate scene.

The streets were as much Basquiat’s home, apparently, as the squat, and the work he made reflects this fact. He scrawled on detritus fished from the neighborhood, on discarded scraps of canvas or a torn-off apartment door, illustrating them with street action: car accidents, ambulances, skylines. These works are very crude—they scarcely even count as juvenilia—but they are also very sweet, and contain hints of what was coming. He began crossing out words as a way to draw attention to them. He was also developing a set of symbols that remained important throughout his career—among them the copyright symbol. It was meant ironically, given that Samo’s work was very much in the public domain. Once he started working indoors, the symbols began to take on a different irony, at once darker and more fragile. Is this work mine? Should I use my given name instead of the Samo tag? If so, will it make me money?

As Basquiat moved toward more conventional painting, he transitioned from streetscapes to human figures. These are shown frontally, with little or no depth of field, and nerves and organs are exposed, as in an anatomy textbook. Are these creatures dead and being clinically dissected, one wonders, or alive and in immense pain?

Adler and Basquiat lived together on East 12th Street from the fall of 1979 to the summer of 1980. That June, he exhibited his work for the first time: He painted a mural inside the “Times Square Show,” the legendary event held in a former massage parlor off Seventh Avenue. The show featured performance art, graffiti, film, and a carnival atmosphere. But it was Basquiat’s contribution that was singled out in Art in America. (“A patch of wall painted by samo, the omnipresent graffiti sloganeer, was a knockout combination of de Kooning and subway paint scribbles.”) The following February, Basquiat was included in the “New York/New Wave” show at PS1, the nonprofit arts space housed in a defunct elementary school in Long Island City. Of more than 100 artists, he was the only one to be given a prominent space for paintings. He showed more than 20 works on their own wall in the final room of the show.

His paintings, the art dealer Annina Nosei later said, “had a quality you don’t find on the walls of the street, a quality of poetry and a universal message of the sign. It was a bit immature, but very beautiful.” Nosei’s background in the art world was deep—she had worked for the eminent dealer Ileana Sonnabend, toured the country with John Cage, met her husband through Robert Rauschenberg. Her connection to Basquiat’s work was instantaneous and serious. She was frantic to represent him, but there was a hitch. Other than what he’d exhibited, he had no paintings. Visiting Basquiat (different apartment, new girlfriend), Nosei was floored to discover that he had no inventory to show her. “You don’t have anything?” she asked him, as she recalls in a 2010 documentary called The Radiant Child. And so, in September 1981, Nosei put him to work producing canvases in her Prince Street gallery’s basement.

The arrangement understandably makes commentators squirm: a white taskmistress keeping a black ward in her basement to turn out paintings on command. Basquiat himself said, “That has a nasty edge to it, you know? I was never locked anywhere. If I was white, they would just say ‘artist in residence.’ ” With its large, oblong skylight, the space was neither gloomy nor cramped, and it was continuously restocked with supplies by fawning assistants. Basquiat treated the arrangement like a job. Nosei recalls him showing up early in the morning with croissants from Dean & DeLuca and apologizing if he was late. Once in the basement, he would put on music, often Ravel’s Boléro, incurring the bang of Nosei’s umbrella from the floor above. And then he would paint.

Here his work begins to mature so quickly, so decisively, one can scarcely process it. At the same time, race enters his work more explicitly. In Irony of Negro Policeman, Basquiat offers his own excruciatingly personal take on what W. E. B. Du Bois famously called “double-consciousness.” Elsewhere, black men for him are at once virtuosos and martyrs, Dizzy Gillespie and Sugar Ray Robinson featured prominently among them. His favored symbol, the crown, appears more often, but what is it, exactly? An Apollonian laurel wreath, the ultimate symbol of victory and honor? Or a crown of thorns, which, along with the cross, is Christendom’s ultimate symbol of humiliation and mockery?

Basquiat worked several canvases at once, dancing from surface to surface like “Ali in his prime,” according to an assistant. He could finish two or three in a day. Sometimes he would paint in pajamas and slippers. At intervals, one of Nosei’s assistants would walk him over to a Citibank to provide him with cash.

Paintings have been tradable commodities since at least the 16th century, and by the middle of the 17th century, something like an international market in art was up and running. It dealt mostly in antiquities and old masters, and was small and illiquid. When a trade in modern art first arose, in the late 19th century, it was defined by an absence of heat or velocity. An art dealer discovered unknown artists, then supported them through years, even decades, of obscurity. “We would have died of hunger without [Paul] Durand-Ruel, all we Impressionists,” Claude Monet famously said of the renowned dealer.

Modern art was once deemed serious because it derived from an avant-garde, and what the garde was in avant of was the market. This much is plain if you read the memoirs of Durand-Ruel, and of his successors Ambroise Vollard and Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, the original dealers in modern art. All three acknowledge the market, and Durand-Ruel and Vollard make constant reference to prices. Kahnweiler invoked Picasso’s dictum: “For paintings to be worth a lot of money, they must at some point have been sold cheaply.” Artistic validation was a process, a struggle that entailed trial and condemnation by the market, then triumphs in the market, which over time revealed the “true” value of the work in high, and finally exorbitant, sale prices.

The appearance of the art market as we now know it has been traced to the early 1970s, and to one auction in particular. In 1973, Robert Scull, a New York taxi tycoon, sold off 50 works of contemporary art. At the auction, Double White Map, an encaustic collage by Jasper Johns, sold for $240,000. For Scull, this represented a 2,250 percent return on his money in eight years. As the sociologist Olav Velthuis discovered through extensive interviewing, dealers and artists point to this as the moment when the “art market proper [turned] into a commodity or investment market.”

And then, in September 1980, the Jasper Johns painting Three Flags was sold to the Whitney Museum for $1 million. This was a record price for a work by a living artist, though it wasn’t only the money that made the sale notable. A Connecticut couple, the Tremaines, had acquired Three Flags in 1959, for $900, from the legendary art dealer Leo Castelli. Selling it, they had bypassed him completely; and this, Castelli felt, violated the established courtesies of his profession.

Castelli had presided over a market that was not a free market at all. It was a field of action dense with personal meaning—handshake agreements, favoritism (in the form of a waiting list and some genteel price discrimination), and, most crucial, a blacklist of collectors who resold works. Together these customs restricted supply, protecting collectors from a flooded market while keeping ultimate jurisdiction over a painter’s career in the hands of his dealer. “It was bucolic,” Castelli said of the period. “Money was not so important.”

The sale of Three Flags made the front page of The New York Times. It heralded, Velthuis has argued, the arrival of “superstar prices” in contemporary art. By late 1982, thanks in part to the onset of the Reagan-era economic boom, a period of reckless, almost spastic, buying had begun in earnest. Whatever else was true, the garde was no longer avant, and prices were rising fast. In 1983, Julian Schnabel’s Notre Dame was auctioned at Sotheby’s for a winning bid of $93,000—a three-year return on investment of more than 2,500 percent. Relationships between artists and dealers were becoming more nakedly transactional. When the painter and sculptor Donald Judd left the prestigious dealer Paula Cooper for the Pace Gallery, Cooper said, “Artists today are like baseball stars.”

In October 1981, Nosei included Basquiat in a group show. She gave his six paintings the entire back room of her gallery, and after his work sold, she was ready to make another proposal. She offered, in a stroke, to put the entire apparatus of the working artist in place around him. She would give him a loft to live in, a studio to paint in, assistants to work for him, supplies, and, waiting at the end of this pipeline, collectors to buy his art. Basquiat had arrived, but he, at least, didn’t seem sure where.

The Crosby Street loft was on the second floor, and visitors would either hit the buzzer, which Basquiat had labeled tar in trademark Samo handwriting, or call up from the street. Collectors would drop in, and if they wondered aloud whether a painting might blend in with their decor, Basquiat would chase them away, often hurling abuse, or sometimes food—cereal, rice, milk—from the window down on their heads. Graffiti kids, groupies, celebrities, and, not least, drug buddies—people came day and night and found a space strewed with art, garbage, toys, magazines, books. A Haitian voodoo statue stood in a corner. The bed had a polyester Superman comforter and a cocaine mirror on the headboard shelf. Reports from this period converge on two details: The television was always on, and the fridge was always filled with gourmet sundries—chocolates, pastries, Russian caviar—slowly going bad.

Basquiat’s girlfriend at the time, Suzanne Mallouk, remembers him covering the windows with black paper, banishing daytime from the living space and the internal clock from their bodies. They did more and more coke, and Basquiat began freebasing. Along with drugs, renown, hangers-on, and paranoia, money was now a force in his life, and large bills were stuffed in books and under the carpet, or left to drift where they may. Basquiat once binged on expensive electronics, then sat on the floor surrounded by his latest gadgets and cried.

In March of 1982, he exhibited work he had made in Nosei’s basement—Arroz con Pollo, Crowns (Peso Neto), Untitled (Per Capita)—in the upstairs of her gallery. This was his first solo show in the United States, and his first solo show as Basquiat. (He had recently shown as Samo in Italy.) It sold out in one night. He was 21 years old. He followed up his debut in New York City with a mob-scene opening in Los Angeles, and a solo show at the Galerie Bruno Bischofberger, in Switzerland.

Shortly after his triumph, he was flown back to Italy, and in an airplane hangar in the industrial outskirts of Modena, Basquiat was deposited in front of massive 25-by-15-foot canvases, stretched and ready, and was given just days to produce fresh material for a second Italian opening. He was attended by his Italian dealer, as well as by Nosei and Bischofberger. “They set it up for me so I’d have to make eight paintings in a week,” he later told The New York Times Magazine. “I made them in this big warehouse … It was like a factory, a sick factory.”

Two months later, he snuck into Nosei’s basement and destroyed 10 of his canvases. Using a box cutter, he slashed them down to rags, and then, as if to make sure that they could never be resurrected as salable art, he doused them with a bucket of white paint.

When I saw “Basquiat: Boom For Real,” the major retrospective of his work that recently closed in Frankfurt, the exhibit was not only well, but reverentially, attended. Viewers paused over items as if they were holy relics. (Someone knew to save this, I thought over and over.) The presentation flowed gracefully from Samo to the East 12th Street material through to the danse macabre of his last major works. Mostly glossed over in the catalog commentary and exhibit photographs was the fact that, after he became famous, Basquiat went, in quick and ghastly succession, from sweet East Village magpie to café-society boor to dead. The artist who presided at the show instead is the pre-boom Basquiat, the marvel of a crumbling yet vibrantly creative New York City. What is he being made innocent of here if not the market, the 1980s art market in particular? Yet to make him innocent of the market is to cleave him in two, and discard the struggle that defined him as an artist.

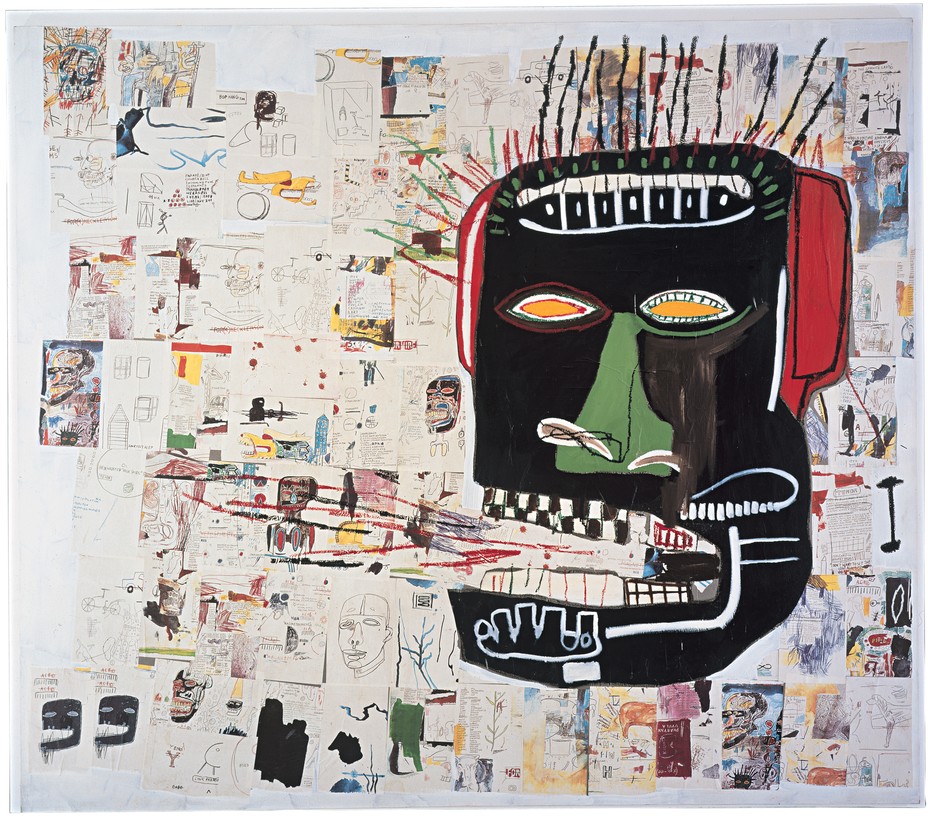

By early 1982, Basquiat had plainly entered a new phase. He started replacing the incidental crud of his surfaces—torn bits of paper affixed with glue, sneaker prints—with something more calculated, deploying techniques of collaging reminiscent of Rauschenberg’s. His use of color, surface, and line to achieve expressionistic affect showed a newfound confidence. At the same time, he was suddenly making paintings for the market, and making a lot of them quickly and under pressure.

The result was a heroic mastery combined with the randomness of trash buoyed in the wind. Basquiat became frenetic in his inclusion of materials he found ready to hand, filling his canvases with yet more symbols: renditions of dollar signs, coins, Federal Reserve notes, Japanese yen, Afro-Cuban ideograms, logos, cars, airplanes, feathers, feet, skulls. To do this, he grabbed at anything that might serve as raw material—from Henry Dreyfuss’s Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols to the 1980 catalog of the Met’s permanent collection. By 1984, his collaging technique had become more sophisticated. He’d sometimes layer the canvas densely with color photocopies, which he would then paint over. He even began using Andy Warhol’s trick of silk-screening to repeat images both within and between canvases.

Warhol reported in his diaries that when Bischofberger first saw these works he gave them a “sour look.” The approach had “ruined [Basquiat’s] ‘intuitive primitivism.’ ” There is a kernel of truth even to this casual racism. Inevitably, words like primitive, unschooled, undisciplined are perilous, given how carefully vetted Basquiat criticism is for offensiveness. Yet if you are afraid, you will never understand who he was or what he was getting at. The curators and critics of “Basquiat: Boom For Real” tried running in the opposite direction, describing him as a maestro in all things, with one contributor to the catalog going so far as to call him an “extraordinary painter and draughtsman.” But Basquiat wasn’t even a good draughtsman, and he cheerfully admitted it. It is useless to pretend otherwise: Unlike Jean Dubuffet, he made unschooled images because he was unschooled. Unlike Picasso’s, his figures were crude because he could barely draw.

To insist that Basquiat was a virtuoso is to turn away from the paintings all over again, to miss their ultimate dare. The search for authenticity of form and feeling that led white artists toward naive (even childish) techniques and human primitives—what does that quest mean when a black artist pursues it? It’s a good question, a biting one, and we’ve become accustomed to asking it of Basquiat while leaving the follow-up hanging in the air: What does it mean when a black artist vaults altogether beyond technique, or formal training, or deep study? On his canvases, Basquiat turned to the black athletes and musicians he venerated, to Hank Aaron and Charlie Parker. They were the consummate virtuosos, yet Aaron was vilified when he displaced Babe Ruth, the greatest of white American athletes, as the home-run king in the sport that is a stand-in for national innocence. Parker, as one of the pioneers of postwar bebop, took “Negro genius” to abstruse places it was never supposed to go.

What does it mean to have depicted them in paintings that are easily misread as lazy, among the most loaded of racist terms? Black American genius has long been forced into music and sports, where it has been asked to further vindicate itself by displaying a total virtuosity, only to be martyred when that genius breaks out of the mold that respectability and conformity has made for it. Basquiat refused to play that game. First, he rejected the role of ingratiating virtuoso, placing himself instead within the lineage of the (white) modernist genius, of “Twombly, Rauschenberg, Warhol, Johns,” as he said. Then he made the martyrdom of the black virtuoso the subject of his work. To be the first black artist who was not a black artist, while never not being a black artist: This is to make of yourself a holy singularity.

The new owner of Untitled, Yusaku Maezawa, has indicated that the proper fate of the painting is not to be hoarded, but to be seen. I went to see the single-painting show “One Basquiat” in March, at the first stop on its global tour, the Brooklyn Museum. The viewing room was chapel-like. At the near end, a glass case held Basquiat’s junior museum membership card. On the far wall hung the most expensive (for now) artwork by an American.

Viewers feel stared at by Basquiat’s paintings, one commentator has said, and I agree. But in their presence, I also have the feeling of happening upon something I was never supposed to see. Basquiat’s art was made under conditions that, one has to believe, are anomalous in the history of art, and yet we would apply to it the traditional standards and vocabularies of art history. On the one hand, Basquiat was a heroic master like Picasso, even though he was rushed to market before he could fully develop his mastery. On the other hand, we need him to be one of the ultimate authentics, à la Vincent van Gogh, even though he interacted directly and on a continuous basis with the market. To this day, he is asked to restore the symbolic capital of the starving artist to a system that otherwise does everything in its power to destroy it. And so he remains, to this day, a perpetually uncertain thing.

Untitled, an agonized skull from the Crosby Street period, was first purchased in 1984 for $19,000. At its recent sale price, it had increased in value by 581,479 percent. One shakes one’s head in disbelief and thinks: Whatever the market will bear. At the same time, one bows one’s head in awe and thinks: Worth every penny.

This article appears in the July/August 2018 print edition with the headline “Searching for Jean-Michel Basquiat.”