This is Part One of a two-part Bay Curious series. Read Part Two here.

D

onner Memorial State Park is a serene place. You might even call it low key, considering its outsized place in history.

If you’ve driven I-80 east towards Reno, and climbed the road high into the mountains around Truckee, you’ve passed it. Safe in your car, up on the ridge on the freeway above Donner Lake, you’ve sped by the site of one of the grisliest, most infamous events in California history.

Here in Donner Memorial State Park, visitors are greeted by the towering Pioneer Monument: a giant column with a statue of a family at its top. It pays tribute to those people, like the Donner Party, who came from the midwest and walked over these mountains in the 1800s, on their way to make new lives in California.

Long before the railroad, these emigrants made the journey with animals and wagons full of everything they owned. Gold hadn’t yet been found in California, that would come later in 1848. At this time, it was land and total freedom, not nuggets, they wanted to claim.

The Age of ‘Manifest Destiny’

In 1846, the “California” to which the Donner Party was journeying wasn’t actually part of the United States. This was still Mexican territory — called Alta California — and it wouldn’t become officially part of the U.S. for another four years.

Of course, this wasn’t empty land either. Before European colonization, California was home to an estimated 300,000 Indigenous people. From the Washoe tribe of the Lake Tahoe area to the Ohlone in what is now San Francisco, the wider Bay Area alone was — and still is — home to many longstanding tribes with incredibly diverse cultures and languages.

Pre-colonization, California was “a bountiful, bountiful place where communities were free to trade, free and interact,” says Dahlton Brown, Executive Director for the Wilton Rancheria tribe in Elk Grove, outside Sacramento.

It was, he says, a life with “no restrictions on existence” for the Miwok and Nisenan people of this region.

Brown’s ancestors are a part of the Donner Party’s story that often gets left out. It was their land that settlers like the Donner Party were trying to reach. What made these white migrants think they could pack up, relocate their entire families and everything they owned to claim this land for their own?

It’s simple, says Greg Palmer, a Donner Party historian who’s worked with the Donner Memorial State Park museum for several decades: “This is the era of Manifest Destiny. President James Polk has propagated the idea that it’s our divine right and duty to build a country coast to coast after the Louisiana Purchase.”

The fact that this land was home for the Indigenous people who’d lived here for centuries, or that it was legally Mexican territory, didn’t stop self-styled pioneers from coming to California. In addition to almost limitless real estate opportunities, settlers like the Donner Party saw an escape from unfavorable situations in their own midwest homelands: places where diseases like cholera and malaria abounded.

“Many people prior to gold were moving west for a more healthful environment,” Palmer says. “Free land, ‘the land of milk and honey,’ opportunity.”

The Donner Party wasn’t just one family called Donner. It was a blended bunch of multiple families, plus some lone travelers and hired hands brought on board to assist: all bound together on a journey of over one thousand miles west.

They were joining many other migrants and traveling in one long snaking party of wheels and livestock along what was called the Oregon Trail; through the grasslands of Illinois, across the desert and, finally, over the mountains into California. And to fully understand just how shocking and unique what happened to the Donner Party was, it’s important to understand that their party was just one of many like them that season. “Hundreds of wagons and thousands of people,” as Palmer says, made it to the West safely.

The Donner Party took a very different path — literally.

Who Were the Donner Party?

Emigrants making the journey west in the 1840s traveled in parties, and the Donner Party was led by 60-year-old George Donner from Illinois, accompanied by not just his own large family, but that of his brother, Jacob Donner. They set out with another local family, the Reeds. That’s the reason this group is sometimes also referred to as the Donner-Reed Party.

Setting off from Independence, Missouri, the group was gradually joined by other would-be settlers: the Breen family from Ireland, the Graves clan, the Keseberg family and many more. At its largest, the Donner Party numbered almost 100 people, including children of all ages — from babies and toddlers to teens.

The majority of the Donner Party weren’t the hardscrabble travelers you might be conjuring in your mind. As Palmer reminds us, “in the 1840s, to go overland to California or Oregon, poor people couldn’t do it. They couldn’t afford it.”

Aside from the hired hands in the party — single men being paid to do the hard work on the journey — most of these families on the trail with the Donners had money and land already. They just wanted a little more of it.

So if there were a lot of folks making this journey West that year, what made the Donner Party different? Put simply, they were the only travelers on the trail who collectively decided to follow not the trusted path into California with all those others, but to take a chance on a new route.

By 1846, migration West had become an industry — and any industry attracts its grifters. One of those was a guy called Lansford Hastings. He’d written a guide to making the journey into California that told travelers of a “cutoff” — a shortcut he promised would save them weeks, and cut out up to 400 miles.

Unfortunately, this route was little short of a scam, based on guesswork. Hastings himself had never taken it, and his travel “guide” primarily recommended it because he wanted to divert travelers into places where he himself had money-making schemes set up to profit off them.

Far from saving them time, Hasting’s cutoff actually added 30 days to the Donner Party’s journey — through heinously difficult terrain that was utterly unsuitable for wagons.

In addition, they were already too late setting off. Hastings’s terrible guide had gotten one thing right: in order not to cross the Sierra Nevada in the snow, travelers needed to leave the midwest at the right time. It warned would-be settlers “unless you pass over the mountains early in the fall, you are very liable to be detained, be impassable mountains of snow, until the next spring, or, perhaps, forever.”

By the time members of the Donner Party left the midwest, they were already three weeks behind schedule. As the last wagons on the trail, their fate was sealed.

Struggles in the Desert

Understandably, a lot of the focus on the Donner Party story tends to fall on the unbelievable horror that befell them in the mountains. One aspect of their saga that this focus tends to obscure: this band of travelers was in dangerous disarray far before they reached any snow.

The extra weeks and miles on their journey from Hasting’s cutoff meant they were already running out of food. Their livestock, which pulled their wagons, were frequently taken by the Indigenous people through whose tribal land they were trekking. They often had to hitch themselves to their wagons when crossing rivers, exhausting themselves as they continued to trudge over inhospitable, jagged terrain they should never have been in.

After having to literally hack a path through the Wasatch Mountains, the 80-mile ordeal of crossing the Great Salt Lake Desert alone took them a week. Hastings had told them it was 40 miles — it was double that.

The death began far before the Sierras. As they desperately pulled their wagons over steep rock, 19th century road rage kicked in — resulting in patriarch James Reed shooting another man dead. For this, Reed was banished and released into the wilderness to make his own way to California without his family. They stayed behind with the Donner Party.

Reed wasn’t the only one to leave the wagon trail. When it became clear that things were already going very wrong for this crew, two other men were sent ahead to California to bring back supplies. Their destination was a sprawling settlement located where Sacramento is now, a place called Sutter’s Fort, presided over by the Swiss colonizer John Sutter.

Sutter’s Fort was Sutter’s miniature empire, and it represented the kind of opportunity that the Donner Party — miserably struggling on the other side of the Sierras — hoped to find in the California sun.

But to the Indigenous people whose land Sutter had claimed, this place held only loss and pain. Sutter first sought to entice the local Miwok and Nisesan people to work for pay at his fort, but when he met those who wouldn’t, he forced them into what a visiting settler called “a complete state of slavery.”

For Dahlton Brown of Wilton Rancheria, tales of Sutter’s cruelty to his ancestors echo to this day. “The man burned down Miwok and Nisenan roundhouses as a way of motivating people to work harder,” Brown says. “And that’s the equivalent of burning down somebody’s church.”

When the men from the Donner Party finally arrived at Sutter’s Fort, Sutter agreed to provide the supplies they requested. But he also “gave” them two young Miwok men to accompany them back into the desert with those lifesaving supplies, and to then help them complete their journey into California. A great deal still remains unknown about these two men, including whether they labored by choice at Sutter’s Fort or were enslaved.

These two men were called Luis and Salvador — names given to them when they were converted to Catholicism by the Spanish missionaries. Their story often gets lost or overlooked in the Donner Party saga.

What was later done to Luis and Salvador by the very people they were sent to help makes that fact all the more painful.

Reaching the Sierras

After multiple weeks in the desert, the Donner Party — already dangerously exhausted, and with barely any provisions — reached the granite cliff-faces of the Sierra Nevada. Just as it was starting to snow.

They approached from where Reno is now, rested, then edged slowly toward where Truckee now lies. Their slowness was another pivotal delay: it could be said, Greg Palmer says, that had they left the Reno area even one day earlier, they might have made it through the mountains safely, and the name “Donner Party” would just be a historical footnote.

On October 20, 1846, this group of 81 adults and children was attacked by a shockingly early snowstorm that kept piling snow multiple feet deep on the ground around them. It didn’t stop for days. The snowstorms most of us have seen in our lives are nothing compared to what the Donner Party saw that year. It was snow that literally buried them.

When the travelers realized they could not go any further, they made camp by what’s now called Donner Lake, at the place where Donner Memorial State Park now lies. But several of them, including the Donner family themselves, were stuck miles behind at a place called Alder Creek.

The Donner Party started desperately constructing shelter from the elements. Some had the strength to fashion rough cabins — but in the unbelievable conditions and nonstop snow, others managed nothing more than lean-to tents made from sticks and canvas.

The families of the Donner Party built their cabins and shelters startlingly far apart. After six months of chaos and violence on the trail these people were sick of the sight of each other. There truly was, Palmer says, “no love lost between the families. It’s every family out for themselves.”

Already running dangerously low on provisions, the travelers trapped in the snow killed the last of their oxen for food — eating first the meat, then the hides. A few attempted to travel through the snow to the other side of the mountain, but were repeatedly forced to turn back by impassable snowdrifts.

As the weeks turned into months, Patrick Breen, the father of the Breen family, began to keep a diary. It’s the only first-person account of the Donner Party horror written at the time that’s seen the light of day.

Wednesday 13th Jan 1847 Snowing fast, snow higher than the shanty, must be 13 feet deep. Don’t know how to get wood this morning. It is dreadful to look at.

Thursday Jan 26 1847 Provisions getting very scant. People getting weak, liveing [sic] on short allowance of hides.

A true battle for survival had begun. And all around them, as the days turned into weeks, the freezing snow just kept coming.

Snowbound Suffering

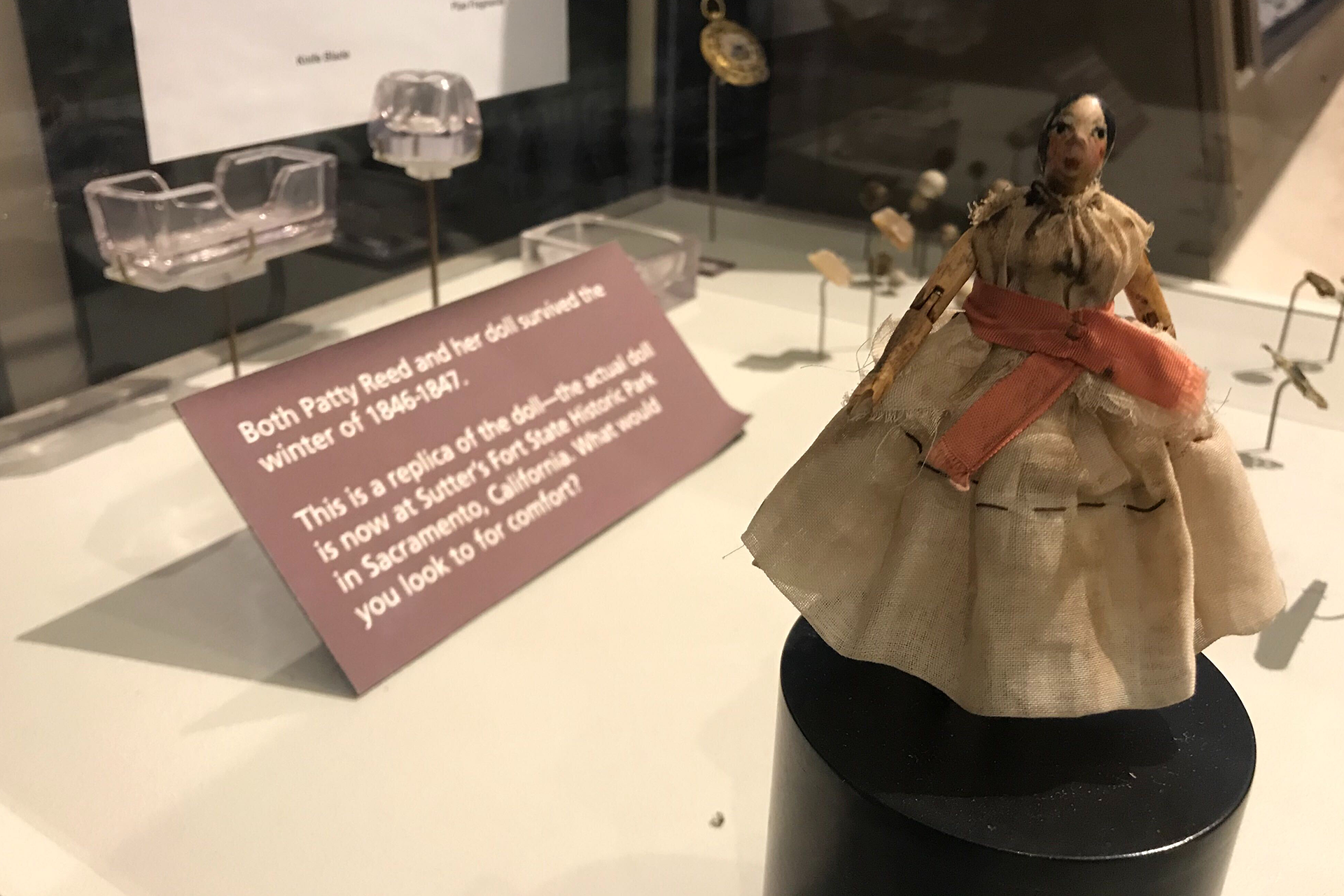

Both the Donner Party camps were filled with children of all ages, enduring one of the most traumatic events imaginable.

Eliza Donner was the youngest child in the Donner family, and was only three years old at the time. One of the few to survive in the family, she eventually wrote a memoir in much later life. In it, she emphasized the relentless isolation experienced by those trapped up in the Sierras: “Oh, it was painfully quiet some days in those great mountains, and lonesome upon the snow. The pines had a whispering homesick murmur, and we children had lost all inclination to play.”

Inside their makeshift cabins, where weak and hungry families huddled to escape the elements, it was dark, and increasingly fetid — especially when the deaths began.

“Days at a time sequestered in the cabins: you can use your imagination and imagine just how gross that was,” Palmer says.

After several weeks, it became clear that if anyone was going to survive, someone needed to go for help.

Fifteen of the strongest people in the Donner Party strapped on makeshift snowshoes, said goodbye to their families and hiked away high onto the peaks above Donner Lake to cross the mountains. With them were Luis and Salvador, the two Miwok men that John Sutter had delivered into this grueling ordeal.

And if things at the camps were bad, things out on the pass, fully exposed to the elements, got much worse quickly. This was where the members of the Donner Party first gave in to their desperate hunger and took the irreversible step towards cannibalism.

Cannibalism and Murder

The snowshoe party — known in Donner Party lore as “the Forlorn Hope” — desperately pressed on with bleeding feet, virtually blinded by the glare of the snow. First one died, then another.

They were too far to return to the camps, so for the first time, the famished, freezing people of the Forlorn Hope band started to talk about the possibility of sustaining themselves on human flesh. When a third man died, the remaining survivors finally took that step, stripped his bones for flesh, and began to eat it.

The notion persists to this day that the Donner Party’s cannibalism never extended to outright murder for food, and that they only ate the flesh of the already-deceased. But unfortunately, that’s not accurate.

When the snowshoe party started to eat their dead, Luis and Salvador were the only ones to refuse, even though they themselves were dying of hunger. For the two Miwok men, to have eaten human flesh would have been “culturally taboo, and an absolute no” says Dahlton Brown.

Seeing their strength waning, that’s when one of the Donner Party, William Foster, murdered Luis and Salvador with his gun — so that the rest of the snowshoe party could eat their bodies, and keep themselves alive.

The fact that Luis and Salvador had brought the Donner Party lifesaving supplies from John Sutter many weeks earlier — effectively saving their lives — made no difference. For Dahlton Brown, Sutter was “sending them up there as a sacrifice whether or not he knew it.” Ultimately, in being killed and used as meat, Luis and Salvador “were treated as no different than any animal the party may have come across.”

In 1995, historian Joseph King used records at Mission San Jose, where he believed Luis and Salvador had been converted, to try to divine more information about the two murdered men. From this, King believed that Salvador might have been a Miwok of the Cosumne tribelet, whose birth name was Queyuen — and that he’d have been around 28 when he was murdered. King believed Luis might have been an Ochehamne Miwok, with the birth name Eema, who was just 19 when he was killed for food.

For Dahlton Brown, it all comes down to who “gets” to write history. “The way the story has been shaped and evolved over time. It really shows you where emphasis was placed when it came to human life,” he says.

“These men’s story deserves to be told,” Brown says. “They’ve really almost been erased from history.”

After 33 days crossing the mountains, sustained by murdering and eating two men, the survivors of the Forlorn Hope party had the strength to stagger into the valley below. And the first people they saw — the ones who helped these half-dead survivors, giving them food and shelter — were people from the Miwok village they stumbled into. These villagers had no idea the party they were helping had murdered and eaten two of their own people just days before.

The First Rescue

Once the survivors made it to Sutter’s Fort, news of the disaster spread like wildfire. As Eliza Donner later characterized the news they brought in her memoir: “Men, women, and little children are snow bound in the Sierras, and starving to death!”

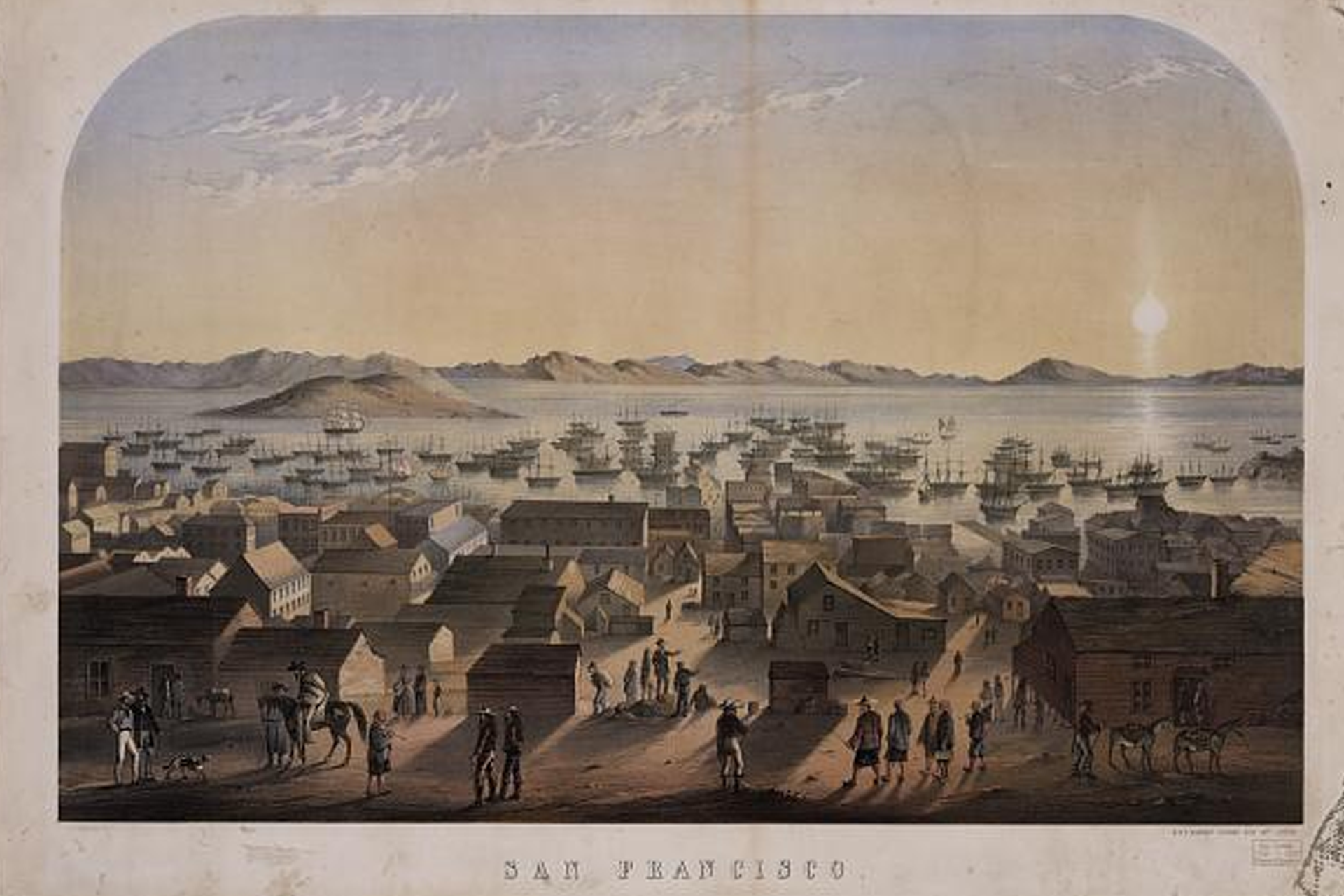

A rescue had to be mounted, but ensuring the safe return of that many people would cost money. An open letter asking for assistance was written from Sutter’s Fort to the people of San Francisco, and was read aloud in the dining room of one of the city’s hotels.

Pre-gold, San Francisco was not a large town — and some of those people listening to that letter had actually been on the emigrant trail with the Donner Party before they took that fateful cutoff. To these travelers safe and warm in that hotel dining room, this glimpse into what might have been their fate was horrifying, and as Eliza Donner later wrote, “the misfortunes which had since befallen the party seemed incredible.”

While San Francisco was digging into its pockets, James Reed — the Reed family patriarch who’d been banished from the Donner Party months before they reached the Sierras — had found that exile had saved his life. He made his way safely to California, and he too was now fundraising for a rescue party, knowing that his wife and children were running out of food fast.

Meanwhile, a rag-tag rescue party of seven men was dispatched from Sutter’s Fort into the mountains. This first rescue party is known as the First Relief.

By the time the First Relief reached the Donner Party camps, 13 people there had already died. And the people they found still living were essentially living under the snow, their cabins blanketed by drifts as high as 15 feet.

What those rescuers first saw when they arrived at the site, says Greg Palmer, were rudimentary chimneys: just “plumes of smoke coming out of a hole in the snow,” and “a woman crawling up out of a hole in the snow, kind of like coming out of a gopher hole.”

One of those rescuers recollected how a woman, gaunt and delirious from hunger, asked him “Are you men from California or do you come from heaven?” But that first rescue party was only seven men, and all they could do was distribute a little food among the survivors, then lead the ones who were strong enough to walk out of the camps.

This was no modern Medevac to safety, but instead the start of a days-long march over the mountains, through snow drifts as high as buildings. In these desperate conditions, and still lacking enough food, several of them died on the rescue route.

Cannibalism Comes to the Camps

Back at the camps, the members of the Donner Party who’d had to watch others being led away to hopeful safety while they themselves were left behind, returned to trying to survive in those rotting, dark cabins.

Eliza Donner was one of them. She recalled the desperation for food — any food. “The little field mice that had crept into camp were caught then and used to ease the pangs of hunger,” she wrote, years later. “Even the bark and twigs of pine were chewed in the vain effort to soothe the gnawings which made one cry for bread and meat.”

It was then that Patrick Breen’s diary made the first mention of cannibalism at the camp, after the death of a young man named Milt:

Friday Feb 26th 1847 Mrs Murphy said here yesterday that she thought she would commence on Milt and eat him.

Eliza Donner’s memoir confirms the fact that the starving survivors at the camp used the dead to “sustain the living.” But not, she said, until mothers had watched their children eat the very last of the food the first relief party had left them days ago — and until wolves had found the snowed-over graves they’d dug for the dead.

“Perhaps God sent the wolves to show Mrs. Murphy and also Mrs. Graves where to get sustenance for their dependent little ones… Was it culpable, or cannibalistic to seek and use the only life-saving means left them?” she wrote.

It was several weeks until a second rescue party arrived, led by none other than James Reed, who’d finally raised enough money and men to go rescue his family.

This time, 17 people were evacuated — leaving only a few members of the Donner Party behind. This included most of the Donner family themselves at their creek camp, which had become a horrific site of death and bodies.

Two weeks later, a third rescue party arrived and evacuated the remaining Donner children.

After surviving being stuck in an incredible blizzard near where Sugar Bowl ski resort now stands, Eliza Donner recalled reaching the safety of the Sacramento Valley, five months after they’d first been stranded in the Sierras:

“There, we caught the first breath of springtide, touched the warm dry earth, and saw green fields far beyond the foot of that cold, cruel mountain range.”

The Final Rescue

Only a handful of the Donner Party were now left behind at the camps, walking skeletons kept barely alive by human flesh. They were either too weak to travel or refused to leave. Eliza Donner’s own mother wouldn’t leave her sick husband and watched her children leave without her.

The very last “rescuers” who made it to Donner Lake in April 1847 were really only making the journey for the salvage. And after so many months of survival, the landscape that greeted these people was one of total horror. Body parts — including heads — were reportedly strewn around the snow.