Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

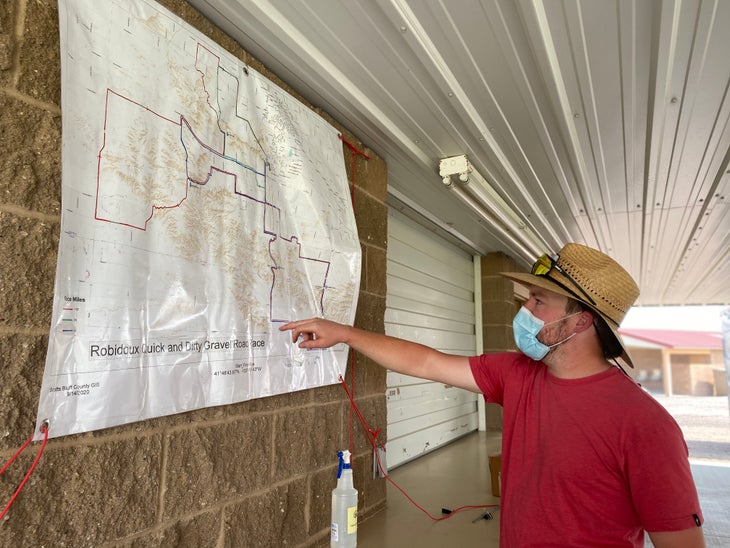

At last weekend’s Robidoux Quick & Dirty gravel race in Gering, Nebraska everyone knew the drill: Wear a mask when you’re milling around; use hand sanitizer before and after you touch things; and hang out at a comfortable distance from one another.

For most of us, those modifications were already just part of life now, whether we’re at a BBQ or the grocery store. Last weekend, I drove from Colorado to the Nebraska panhandle to see how things would feel at a gravel race — and I was pleasantly surprised.

Related:

- Inside The Mid South’s decision to proceed as the coronavirus escalated

- The Spirit World 100 — and other grassroots gravel events — offer more than just a finish line

Gravel gets smaller

The last time I raced gravel was at the wet, and frankly, weird Mid South last March. There’s not much to say about it except that for me, The Mid South marks the moment when We Knew. Sports, bikes, and life shut down for a while after that fateful weekend, and as the COVID-19 pandemic ripped through communities, it wasn’t long before gravel racing seemed like a thing of the trivial past.

At that time, Robidoux Quick & Dirty took an optimistic tack and rescheduled its June 20 race date to September. Other races did this too, yet many eventually canceled due to concerns that a large volume of visitors to a small community was in neither’s best interest.

The Robidoux Quick & Dirty, in its third year, initially capped out at about 390 riders spread across three distances (25, 65, and 100 miles). Race director Aaron Raines told me that about 50 riders requested refunds or deferrals after the COVID-19 date change. On race weekend, 175 checked in.

“I’m assuming a lot of folks weren’t comfortable with coming and just didn’t tell us,” he said. “Which I can totally understand and we did our best to accommodate everyone who did reach out. The smoke in the area also didn’t help encourage people to come.”

Like me, Ashton Lambie, the Nebraskan-bred gravel rider who has also broken records and won medals on the track, hadn’t raced gravel since The Mid South. He said that the Robidoux Quick & Dirty seemed like a good way to wade back into the proverbial water of organized bicycle races.

“I’ve done a few the quarantine races where it’s an agreed-upon long-distance TT which unsurprisingly I like a lot,” he said. “That’s what drew me to this one. I don’t think I was feeling safe enough for a full-stop, mass start. This was a really good middle ground where it still felt really safe.”

On the ground

My favorite thing about gravel racing is rarely the racing. Rather, it’s the small towns I’d never otherwise get to see and the people I meet. I know that to be true for many people, which is why I thought gravel promoters should press pause until we could all hug, high five, and have a post-ride beer together.

It turns out, there are ways for gravel to survive in the new world we live in, and they were on display at the Robidoux Quick & Dirty. As with all events that are slowly rolling out this year, the race published its COVID-19 plan two months prior to race day. This included details on the process for signing waivers, packet pickup, start line procedure, aid stations, and awards.

When we arrived at the Five Rocks Amphitheater to check-in, everything seemed to go according to plan. I had printed waivers back at home, so check-in was as easy as handing it to a (masked and gloved) volunteer in exchange for a number plate. There was a swag bag to grab on the lawn on the way out. And — riders had five hours to complete that five-minute process.

On race day, Raines offered riders options for how to start. Again, wearing a face-covering was almost redundant at this point – everyone knew it was required. Otherwise, people could start together or staggered. I chose to go out in the front, which didn’t last long, but the biggest group was never that big.

“At any given point I was only ever riding with a few people,” Lambie told me.

We were encouraged to bring our own nutrition, although there were four aid stations along the 100-mile course. They were manned by volunteers in PPE, and all of the food was individually wrapped. Riders opened their own bottles to hand to volunteers to fill from pitchers. It was easy.

Although other events have done away entirely with any post-race festivities or awards ceremonies, we were treated to both at the Robidoux Quick & Dirty. The podium consisted of socially-distanced 12-packs of Fat Tire Ale, and riders lounged around on the huge lawn, under the pavilion, and in the stands at the Five Rocks Amphitheater. The combination of ice-cold beer (which you could retrieve from an industrial-size trough full of ice) and the sounds of classic rock cover bands Area 308 and the Greendales made for some happy, dusty riders.

Gravel’s future amid COVID-19

Of course, so much of the success of an event is based on personal responsibility. For me, this meant holding in a snot rocket that I desperately wanted to eject for about 30 miles. Realizing that I’ve become lax on my hand hygiene at home and thus being extra vigilant while traveling. Not shaking hands even when they’re extended.

It’s hard to say what the near-future of gravel racing will look like. I asked Lambie, and he lobbed the question back at me. Just as I can’t predict when I’ll go to a concert again or what the 2021 school year will look like, I’m not holding out for the gravel parties of yore anytime soon. Nevertheless, as I learned in Nebraska over the weekend, there are ways to navigate the new world we live in, and race promoters and riders are willing to go to a certain distance to make it happen.

Riding gravel is just too much fun.