Inside the Nevada county that the coronavirus has skipped — so far

When news hit rural Esmeralda County in March that a lethal global virus was on the march, Linda Williams knew precisely what to do.

For 42 years her family had run the general store in tiny Dyer, an unincorporated assemblage of farmers and retirees four hours north of Las Vegas. She knew most residents because her store was a longtime central gathering spot, 75 miles distant from the nearest chain grocery store.

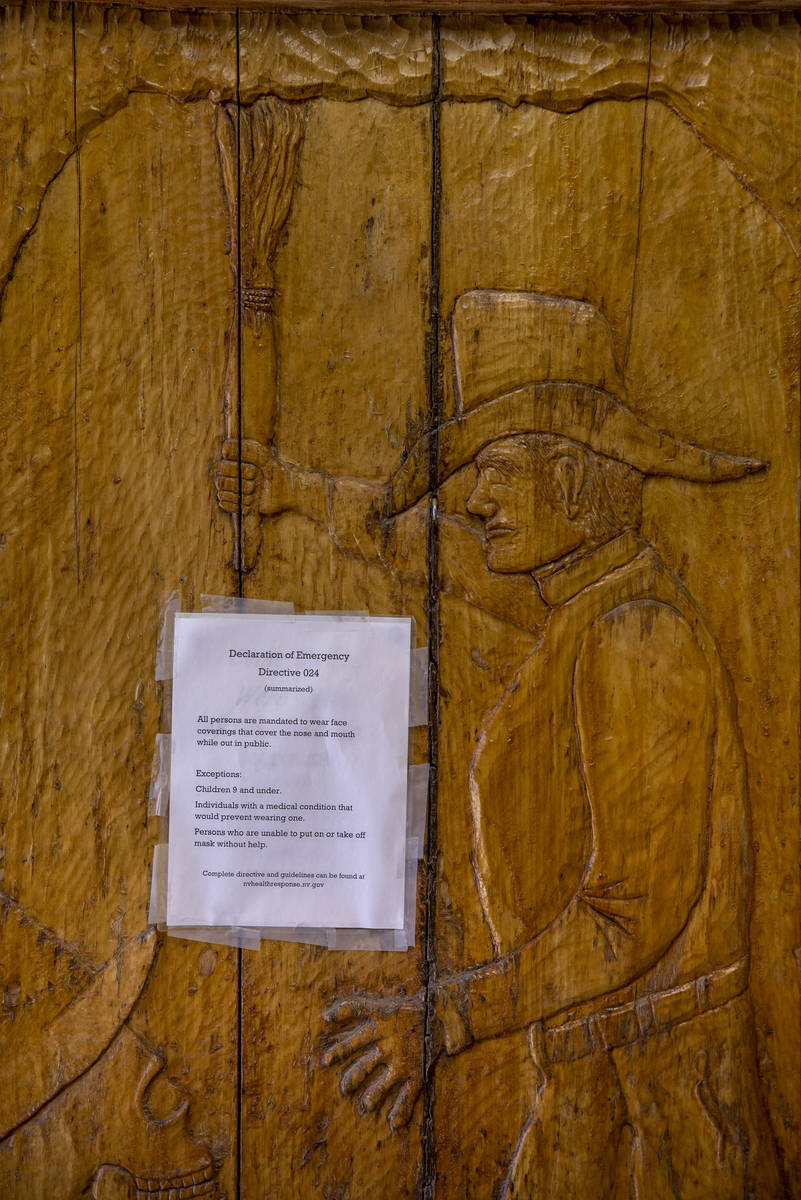

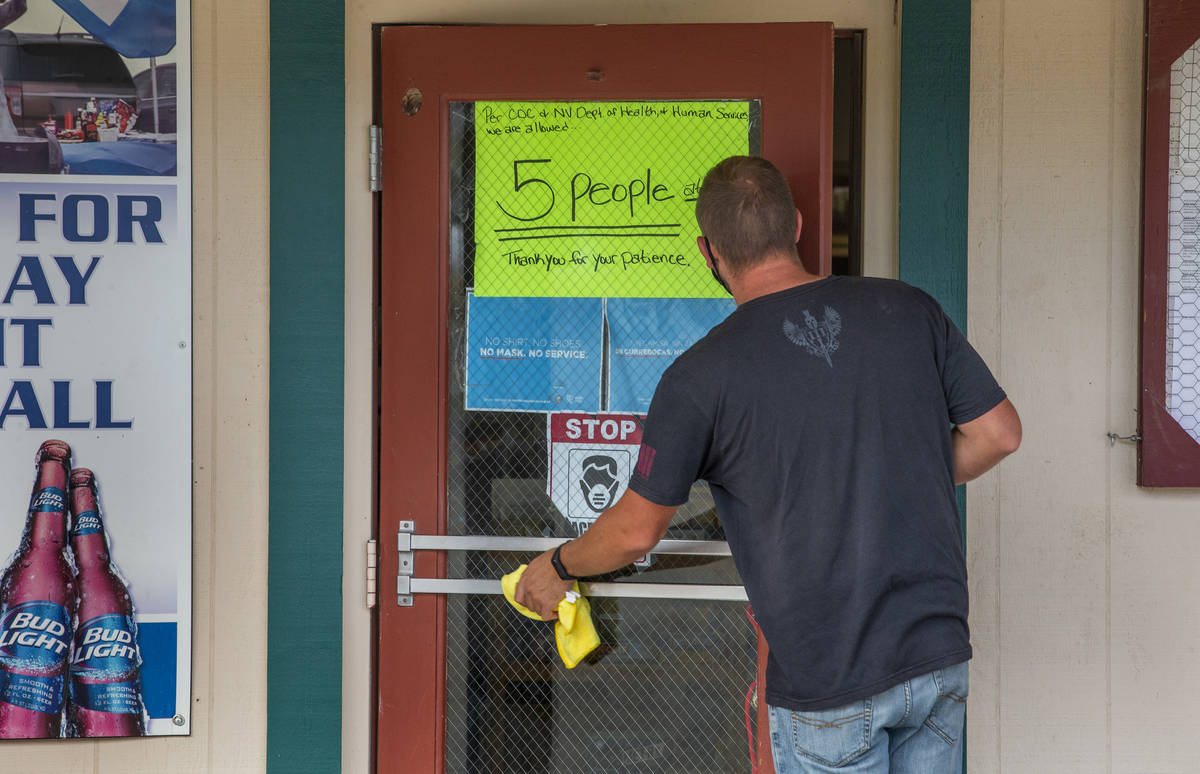

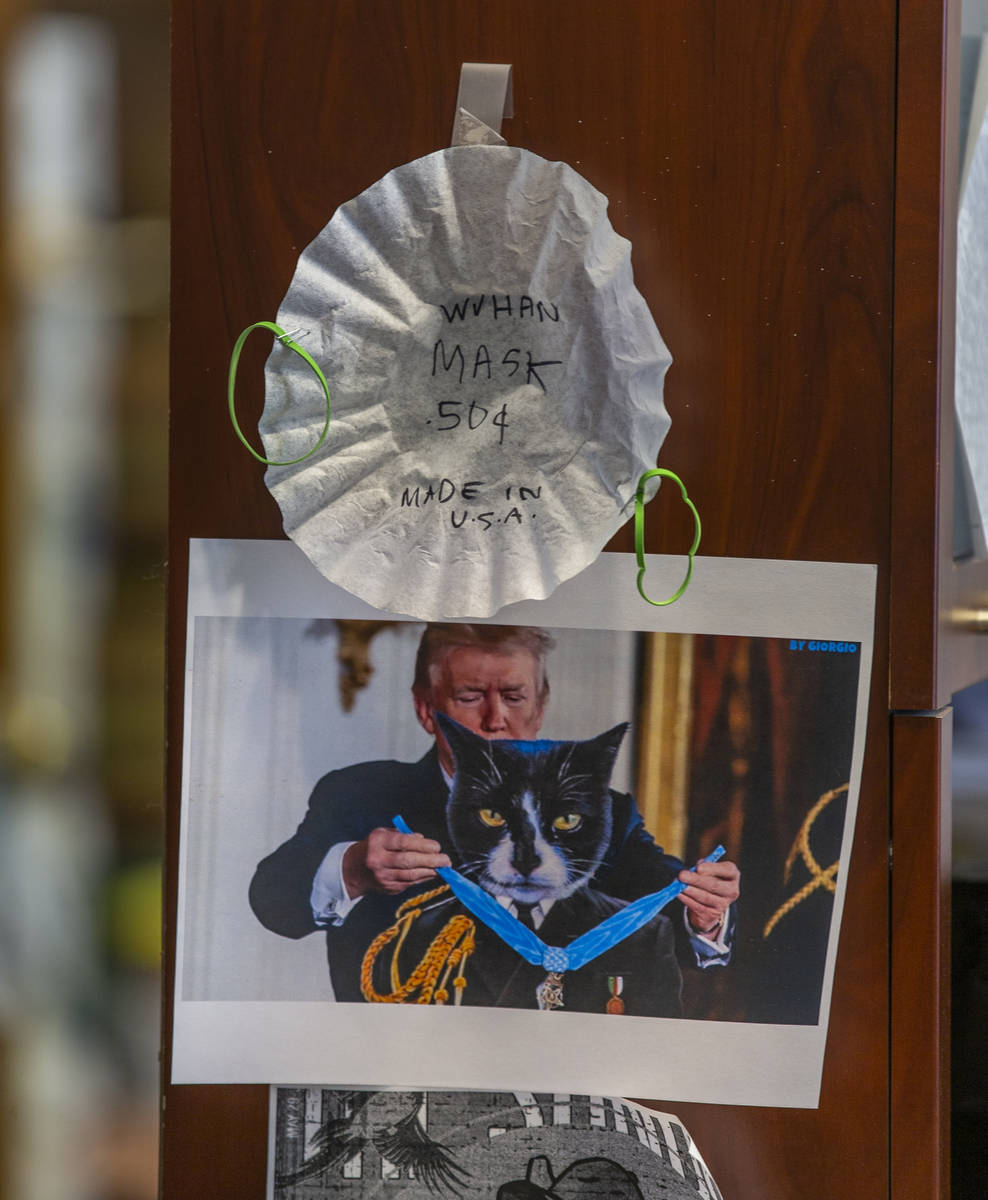

Every day, she monitored the governor’s latest health mandates and helped organize an effort to knit homemade masks she gave out for free in her market, where a sign at the door limited customers to three at a time.

She cleaned and disinfected the store, constantly, like a woman possessed.

“I was on it like Donkey Kong,” she said. “My message to customers was ‘I will protect you. You are my responsibility.’ We reminded them as soon as they walked through the door about wearing a mask and keeping their distance.”

And, so far at least, it has worked.

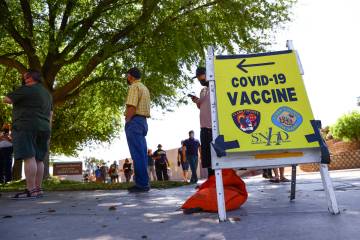

Esmeralda is the only Nevada county to report no COVID-19 cases, a rarity in a state that has seen more than 60,600 cases and 1,069 deaths. There are reasons, of course.

With a population of just 974, Esmeralda County is among the nation’s least-populated counties. Social distancing is a way of life in a place with no incorporated communities, no high schools, no traffic signals and just a handful of stop signs.

The county features three population hubs: 350 inhabitants live in the county seat of Goldfield, 150 in Silver Peak and another 350 in the westernmost Fish Lake Valley, located on the California line, home to Dyer and Williams’ general store.

Residents are proud of avoiding the virus, pointing to a sense of community and collective common sense necessary to carve out a life far from the big city.

A matter of time?

Health officials have yet another possible explanation: They’ve dodged a bullet.

“They are really lucky to not have COVID introduced into their community yet,” said Trudy Larson, dean of the school of community health sciences at the University of Nevada, Reno and a member of the governor’s medical advisory team.

While most of Esmeralda County’s residents live well away from main state highways, Goldfield sits along U.S. Highway 95, the main route between Reno and Las Vegas.

“This virus travels with people, so it may just be a matter of time,” Larson said. “Distance between people helps reduce transmission, but it takes just one person to introduce it into the community. Especially along a busy highway, where someone stopping for gas or getting something to eat could bring the virus.”

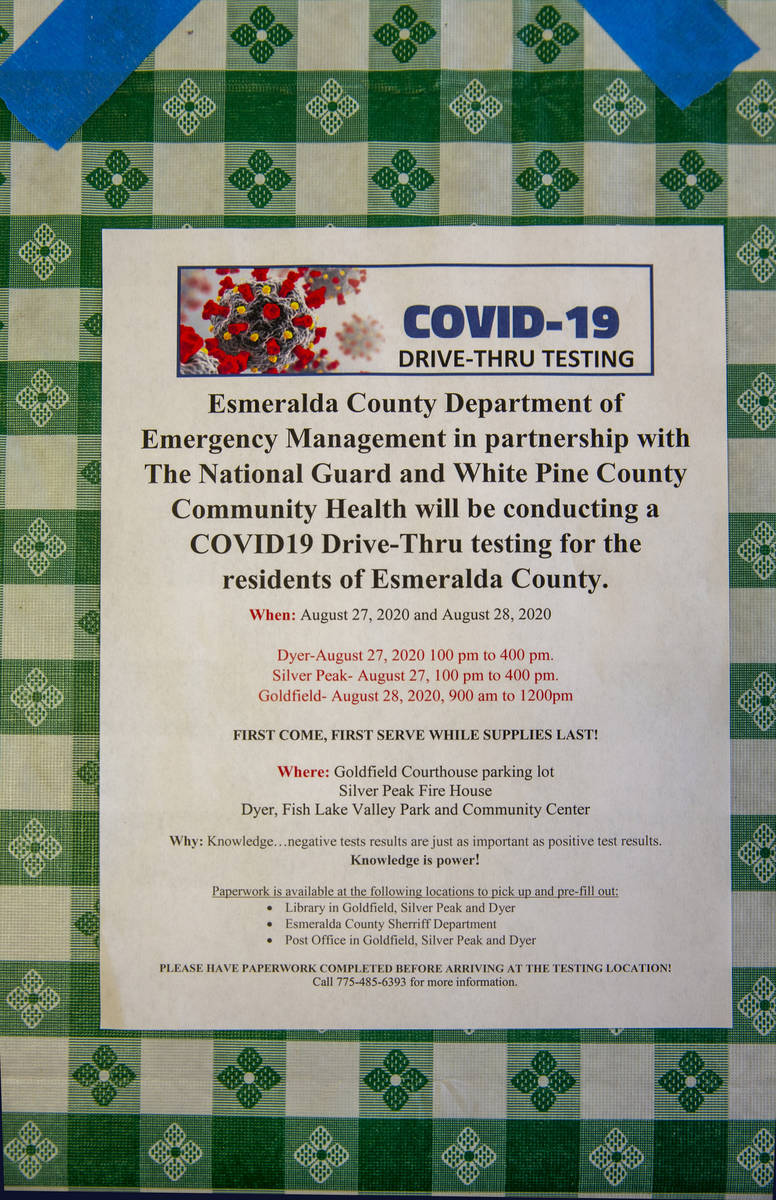

In Esmeralda County, testing for the virus has been low. Without a hospital or clinic nearby, Esmeralda County residents must travel to Tonopah in Nye County to be tested for the virus. Through early August only 73 people had done so, about 7 percent of the population, which is about half the statewide rate of 15 percent, Larson said. More may have gone out of state to be tested in Bishop, California.

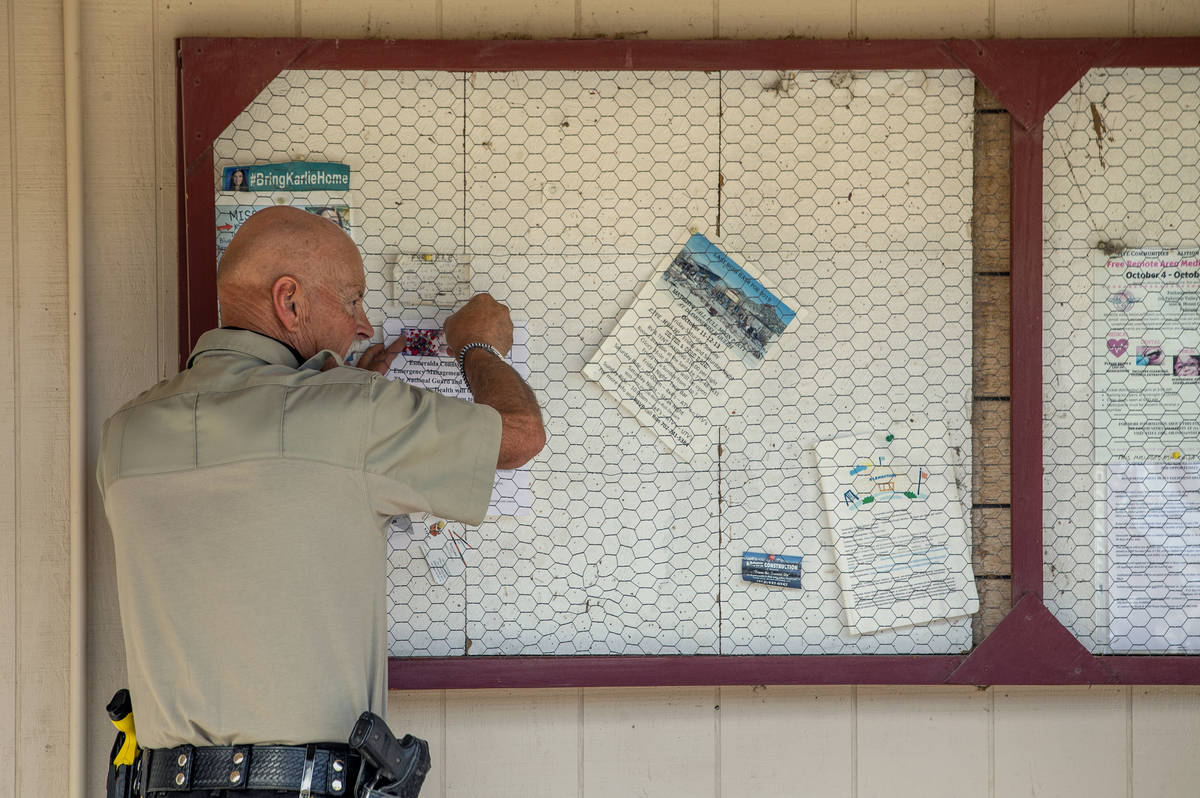

County officials are looking to remedy that discrepancy.

Ralph Keyes, a farmer and one of three county commissioners, said Esmeralda has formed a health board in response to COVID-19 that is investigating bringing a National Guard mobile testing unit that could visit even isolated locations.

“I think our success is a combination of local vigilance and our lifestyle,” Keyes said. “This is a rural community. Everybody is spread out.”

In the mine town of Silver Peak, regulars at the Old School Bar toast one another on their success at staying one step ahead of the virus. Still, Goldfield resident Patty Huber-Bath keeps her fingers crossed. “I tell people that Esmeralda County still has zero cases that we know of,” she said. “I always add that last part.”

Esmeralda County Commissioner Timothy Hipp says he knows the virus will come one day. “I’m nervous even talking about it, that I’m going to jinx it,” said Hipp, 47, a local mineworker. “As soon as it comes out that we’re acting proud of not having any cases, we (will) get one the very next day.”

And when that day comes, he said, it could hit the county hard.

“We have the state’s highest proportion of elderly people, who would be susceptible to the virus. And we’re so small that all of our services are located in one building. So if someone with the virus walks into the Goldfield courthouse, they could infect the court people, jail inmates, district attorney, public defender. We could be in serious trouble.”

Locals looking out for locals

For the most part, averting the virus has meant locals looking out for locals.

Keyes said Fish Lake Valley residents donated gloves and masks. A woman’s club there that got its start in 1929 making quilts began knitting masks that were handed out to local classrooms and among senior citizens.

Everybody did their part. “We normally get kind of huggy-huggy out here, but we started resorting to elbow bumps,” Dyer resident Patty Hudson said.

Not only that, but the Saturday night cribbage game at the Fish Lake Valley Saloon was put on hold. The annual July Fourth festival in Goldfield was reduced to a few fireworks, and the county seat also canceled its popular Goldfield Days in early August.

While judges in the Goldfield courthouse required workers and defendants to wear masks, they often had to ask them to pull them down to be understood during hearings. After each run to the nearest hospital in Bishop, EMTs scoured their ambulance with sanitizer and even changed their clothes.

Locals who left town on monthly shopping trips took orders from neighbors, especially the older ones, so they didn’t have to leave home. State health officials did video inspections to ensure businesses were following the latest disinfecting protocols.

Rather than feel isolated, Esmeralda County residents revel in the cultural and geographical detachment — of one of Nevada’s original counties, established in 1861, where ghost towns outnumber peopled communities. Writer Mark Twain spent time in the area as a miner while researching his book “Roughing It.”

Neither paved roads nor electricity arrived until the early 1960s. With no building codes, Esmeralda County attracts outsiders tired of big-city regulations. While serious crime is low, residents pack concealed weapons, and a sign posted inside the Dyer general store bears two six-shooters and reads: “We Don’t Dial 911.”

A T-shirt for sale there reads “Where the hell is Dyer?” while another shows a road mileage sign that says “End of the World: 9 mi. Dyer, Nev: 12 mi.”

‘All in this together’

The national shutdown has meant fewer outsiders. Goldfield has seen less U.S. 95 traffic and fewer tourists passing through Dyer en route between Yosemite and Death Valley national parks.

“People think little communities like ours don’t pay attention just because a lot of big cities don’t,” Williams said. “It’s not as though we like having to take all these precautions, but we realize we’re all in this together.”

Following the shutdown, Gemfield Resources, which operates a local mine, donated $150,000 to the county for economic development, including $50,000 officials used to create vouchers at local food outlets, to help keep residents close to home.

For seven straight weeks, until the money ran out, each Esmeralda County resident received a $20 voucher. The move not only provided food for the community, but kept employees in their jobs and the doors of local businesses open.

Still, at 82, Fish Lake Valley resident Jeanie Amick took no chances.

“I followed the rules,” she said. “When I went to the Dyer general store, I disinfected my hands before and after. When I left, I used my body to open and close the door.”

And if Amick and others spotted vehicles with out-of-state license plates outside the general store, which attracted outsiders looking to buy fireworks before July Fourth, well, they just drove on by.

There have been struggles to keep the peace.

Since the conference room at the Goldfield courthouse is too small to maintain social distancing, somebody suggested that county commissioners move into the courtroom for their regular meetings.

But the judges weren’t having it.

“We told them, ‘We’re willing to work with you, but this is a courtroom and we will be having court,’ ” said District Court Judge Kimberly Wanker, who hears cases in Goldfield.

Commissioners rescheduled their meetings for when court was not in session.

Williams has an extra reason to fear the virus. Now in her 70s, she is undergoing chemotherapy for an autoimmune disease. She knows she’s vulnerable.

When some general store customers refused to wear masks, she took it personally.

“We had some confrontations,” she said. “Some locals pride themselves on their mountain ruggedness. They have this attitude that they’re invincible. They live in God’s country, they trust in God and they’ve got strong immune systems.”

But for the most part, Esmeralda County residents are proud of the way they’ve handled the novel coronavirus, whether it finally reaches them or not.

Williams, who recently sold her business to concentrate on her health, told the story of a California Highway Patrol officer who walked into the market without a mask.

“I told him, ‘Hey, you’re welcome here, but where’s your mask?’ ’’ Williams said.

The officer responded, “Oh yeah, you’re right” and returned to his car to get one.

The next you know, Williams said, he walked back inside “wearing one of those big honking N95 masks, like he meant business.”

Later, he saw the pile of free masks and donated $100 for a handful, which he planned to hand out to shut-ins. Williams used the money to buy food for four needy families.

“We all came together,” she said. “And all the little things, they add up.”

John M. Glionna is a former Los Angeles Times staff writer. He may be reached at john.glionna@gmail.com.