Editor's Note: This is the fourth part in a weeklong series examining racial issues and their history in Polk County. The project by The Ledger staff is titled "Black In Polk."

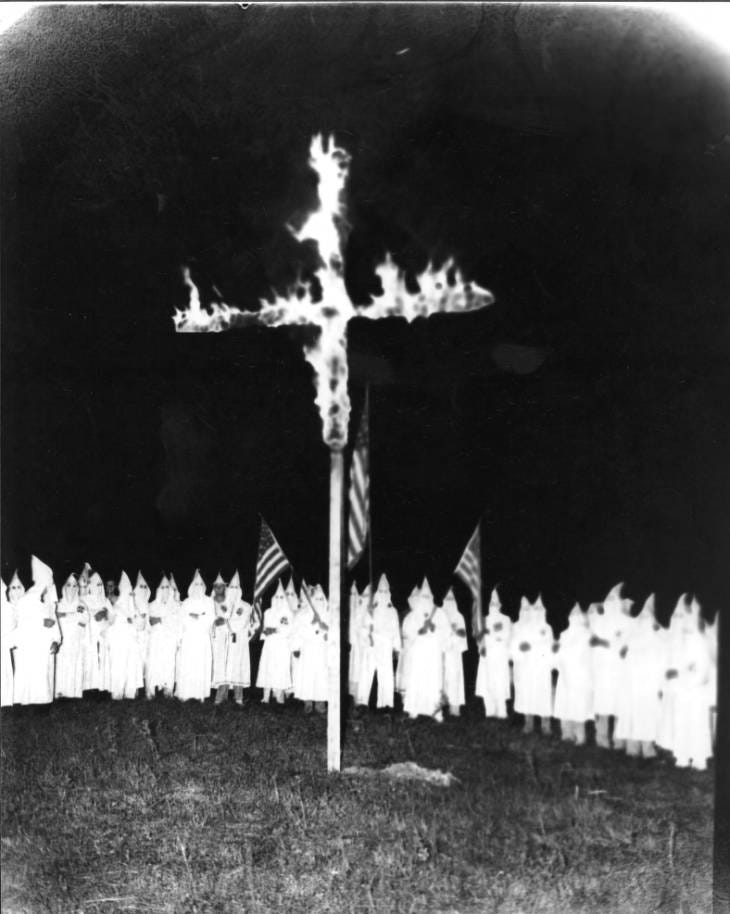

LAKELAND — Very little could strike more fear in Black people than seeing a gang of men dressed in white robes and hoods or a cross burning in the night.

Those things happened in Polk County with regularity throughout the 20th century as the Ku Klux Klan operated nearly unfettered for more than 100 years, with their last local public appearance in 1995 in front of Auburndale High School.

BLACK IN POLK: DAY 4>>White supremacists in Polk County, but not organized into a group

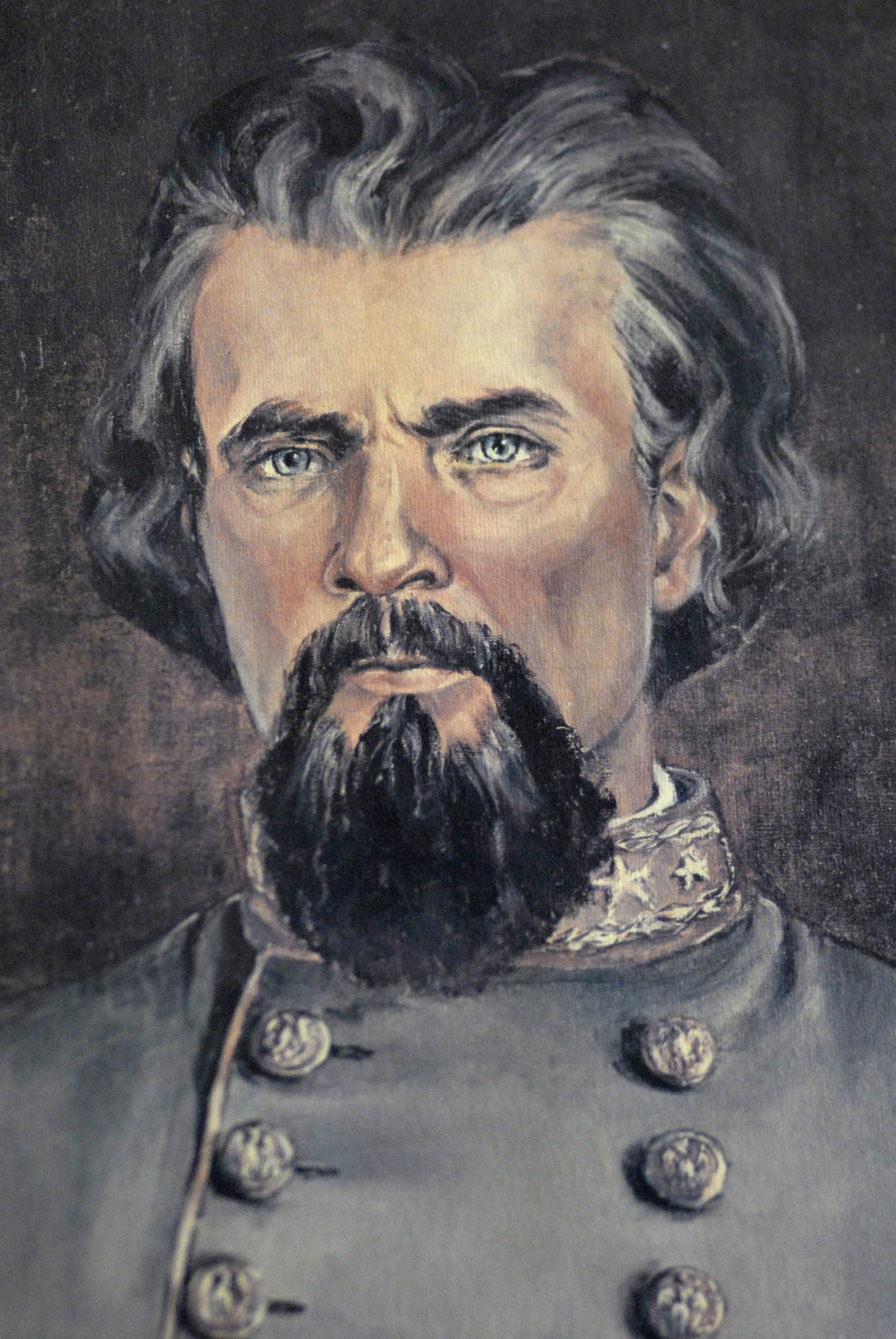

According to history.com, the Ku Klux Klan was founded by former Confederate soldiers the year after the Civil War ended, including former Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest. Nearly every southern state had a chapter by 1870 and its members terrorized Republican party members, who were working to establish equality for former slaves.

The KKK’s members, who included lawmakers, law enforcement officers and prominent business owners, began passing Jim Crow laws, which legalized segregation — the separation of the races. Black people could not eat in “whites only” restaurants, drink from the same water fountains as whites, use the same restrooms, sit in the same areas in movie theaters, or live in the same neighborhoods. They instituted poll taxes, a fee charged to Blacks to vote, which many could not afford to pay, and they limited bank loans to Blacks to keep them oppressed.

BLACK IN POLK: DAY 1>>Polk's Black history continues to shape community

Sharecropping was also created during this time period. Tenants worked the land of property owners and were supposed to get a share of the crop’s profits. It wound up being an extension of slavery for most Southern Blacks or a type of perpetual indentured servitude for poor whites.

Florida’s mob justice

In 20th century Florida, the Klan and mob rule saw several notorious incidents.

According to the Equal Justice Initiative, in 1920, a white mob pulled four Black men accused of raping a white woman from jail in Macclenny, near Jacksonville, and lynched them.

BLACK IN POLK: DAY 2>>Slave descendants recall youth in Black settlement of Bealsville

That same year in Ocoee, near Orlando, two Black residents tried to vote during an election. Several history and media outlets, including the Orlando Sentinel, said a confrontation ensued and two white election officials were shot, after which a white mob destroyed Ocoee's Black community, causing as many as 30 deaths and destroying 25 homes, two churches and a Masonic Lodge.

In December 1922, whites burned a Black man, Charles Wright, at the stake and attacked the Black neighborhood of Perry after a white school teacher was murdered, the EJI reported. The next day, whites shot and hanged two more Black men in Perry, then burned down the town's Black school, the Masonic Lodge, a church, amusement hall and several families' homes.

According to newspaper accounts at the time, on Dec. 31, 1922, the Klan had held a parade and rally of over 100 hooded members in Gainesville under a burning cross and a banner reading, "First and Always Protect Womanhood."

BLACK IN POLK: DAY 2>>Mulberry couple told of horrific life as slaves

According to a state investigation conducted in the 1980s and 1990s, the next week a white woman said she had been beaten by a Black drifter and the mainly Black town of Rosewood, near Cedar Key, was burned down and at least six Black people and two whites were killed — although some estimates put the number of Black deaths closer to 27. One eyewitness told investigators decades later that they remembered a plow brought from Cedar Key that covered 26 bodies. Residents from the town hid for several days in nearby swamps until they were evacuated by train and car to larger towns.

No arrests were ever made for what happened in Rosewood and no one ever returned.

In 1949 in Groveland, four Black men were arrested for the rape of a white woman. One man escaped, but was tracked down, shot and killed. A coroner's inquest was unable to determine who killed him, as he was shot some 400 times. A mob convened in Groveland and burned down several buildings. Two suspects, Sam Shepherd and Walter Irvin, later told the FBI that they were beaten until they confessed. They were convicted and sentenced to death, but the U.S. Supreme Court overturned their convictions.

In November 1951, Lake County Sheriff Willis McCall was personally transporting Shepherd and Irvin from Raiford to Tavares for the retrial. He shot both prisoners, claiming self-defense. Shepherd died at the scene, but Irvin, whom McCall shot three times, survived. He was found guilty a second time and sentenced to death, but Gov. LeRoy Collins commuted Irvin’s sentence to life in prison. He was paroled in 1968 and died the next year while visiting Lake County.

Following the earlier beatings in the Groveland case, Florida NAACP President Harry T. Moore called for McCall’s suspension from office and an investigation of prisoner abuse. A month after Shepherd and Irvin were shot, a bomb exploded under Moore’s home, killing him and his wife. No one was ever arrested. In 2004, then-Attorney General Charlie Crist reopened the case and in 2006 announced the names of four suspects, who were all dead. According to Crist’s investigative report, all had a long history with the Ku Klux Klan, serving as officers in the Orange County Klavern.

Unions versus Klan

The Ledger's extensive archives on the Klan date back to the early 20th century.

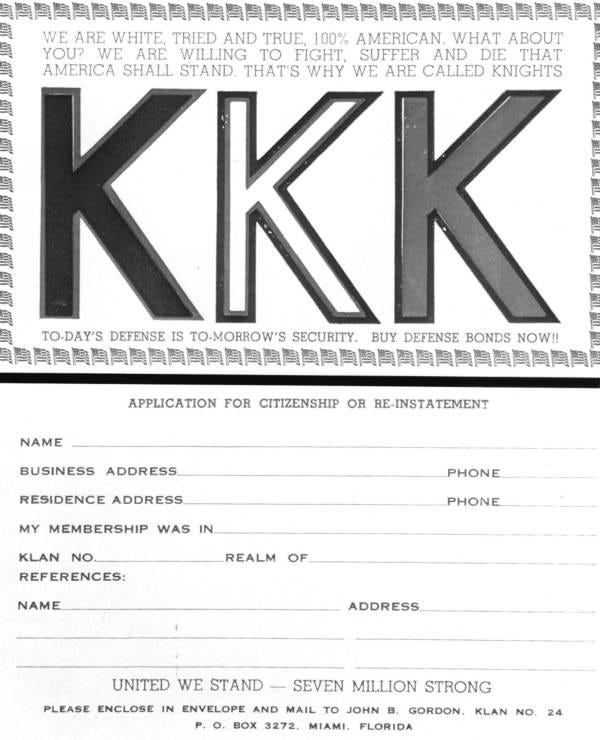

The KKK first appeared in Polk County in the 1920s, when the Klan was gaining ground in various parts of the nation, not just the South. The group attracted a large number of Polk County members — Lakeland’s Abraham Lincoln Klan #5, in fact, was the first in Florida to get its own lodge building.

BLACK IN POLK: DAY 3>>Being Black in Polk County means consistent struggle with racism

“The Klan appealed to those seeking ‘a return to Protestant, (white)-American values'," Canter Brown Jr. wrote “In the Midst of All That Makes Life Worth Living.” “The new KKK theme ‘One hundred percent Americanism’ masked negative attitudes toward anyone not a white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant. Organizers framed members’ principal activities as social gatherings for men and for families, but extremist elements prepared for violent action.”

“When the so-called ‘Red Scare’ erupted after World War I, Floridians launched a series of campaigns against alleged black radicalism, non-Protestant religions, and 'un-American' conduct. The Ku Klux Klan was extremely aggressive in Florida in defending ‘Americanism’ against communism, socialism, and ‘the other isms'."

In August 1938, as grove workers in Polk County tried to organize a union because of low wages and planned to picket, grove owners turned to the Klan for backing, according to the January 1993 Florida Historical Quarterly essay “Communists, Klansmen and the CIO in the Florida Citrus Industry” by Jerrell H. Shofner.

“When the so-called ‘Red Scare’ erupted after World War I, Floridians launched a series of campaigns against alleged black radicalism, non-Protestant religions, and 'un-American' conduct,” Shofner wrote in the essay. “The Ku Klux Klan was extremely aggressive in Florida in defending ‘Americanism’ against communism, socialism, and ‘the other isms'."

RELATED STORY>>Lynchings, Klan activity part of Polk’s history

Shofner said when citrus workers began organizing activity in the early 1930s, the Florida Klan, allegedly the largest in the nation at the time, suppressed it swiftly and fiercely.

“Night-riders in Orange and Polk counties beat several organizers, and at least one disappeared permanently,” Shofner wrote. “Frank Norman left his Lakeland home in early 1934 to attend a meeting and was never seen again.”

The next year, Joseph Shoemaker, “a mild-mannered socialist residing in Tampa,” began organizing a group called the Modern Democrats.

“Klansmen, with the apparent complicity of the Tampa police department, abducted and beat him and two of his associates,” Shofner wrote. “Castrated and tarred and feathered, Shoemaker died in a hospital after nearly two weeks of suffering."

Six Tampa policemen and several Orlando Klansmen were eventually acquitted of all charges of murder and kidnapping.

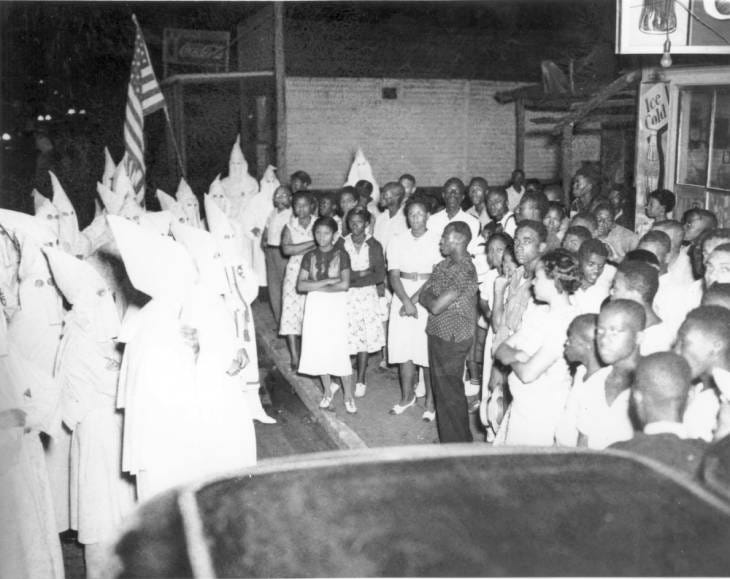

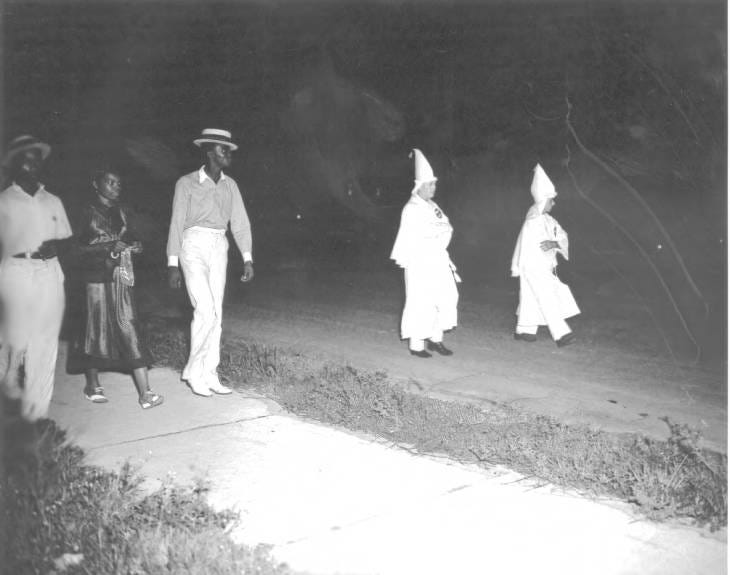

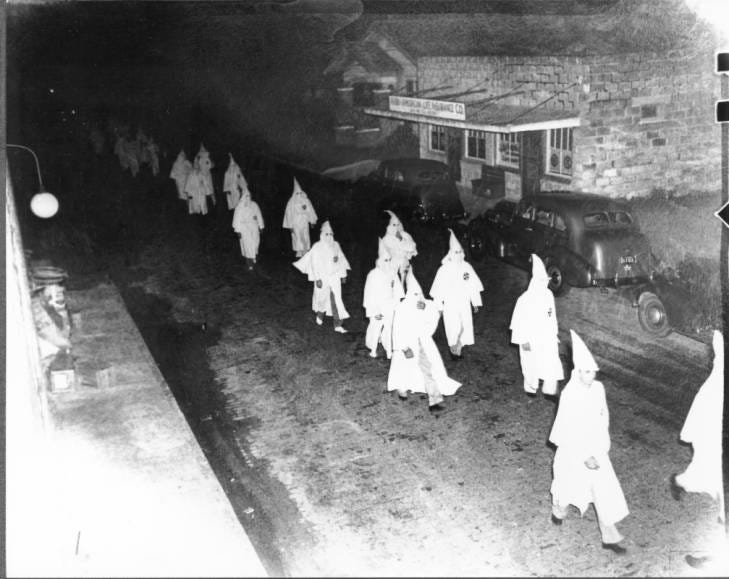

On Aug. 31, 1938, the night the Lakeland City Council met to discuss relaxing a law against workers picketing their employer, 200 robed and hooded Klansmen paraded through Lakeland’s Black Moorehead neighborhood (where the RP Funding Center now sits), held a rally and then burned a large cross. Many of the residents were citrus pickers, railroad workers and phosphate miners. Photos of the event taken by Dan Sanborn, now on file at the Lakeland Public Library, wound up in Life magazine. An Associated Press story that appeared in the New York Times, however, said the Klan gathering was in response to “two Negro slayings here in two weeks ... which occurred at Negro dance halls.”

Even more astounding was the fact that Black residents actually confronted the Klansmen as they marched along Dakota Avenue — now Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.

But another Klan march and rally was held in Winter Haven — including 400 Klansmen — and Auburndale on Dec. 5, 1938.

By Dec. 8, at least one grove owner, John Snively, who was head of the Polk Packing Association, rescinded the wage cuts he had announced earlier in the year.

Historian Canter Brown Jr. cites the first civil rights protest in the county as taking place in 1943 when the School Board closed Black schools for three months in order to give the citrus industry access to child laborers. The protest was successful and the schools were reopened.

The New York Times featured a story about a Klan rally on July 20, 1956, when 200 Klansmen in robes and hoods, along with 1,000 people in street clothes, gathered in a pasture owned by Sawyer’s Dairy near Lakeland to protest public school integration. A counter protest was held at St. Lukes Free Will Baptist Church, which had a predominantly Black congregation.

Desegregation

In the 1960s, as Civil Rights legislation from Washington took hold, and schools began to integrate white and Black students, and Jim Crow laws began to topple one by one, the Klan and white supremacists tried to take the law into their own hands.

In 1965, a group of young Black people showed up at Auburndale's Lake Ariana Beach, an all-white swimming spot.

Jimmy Earl, 18, was a standout football player at Auburndale High School and had been accepted by his white peers because of his talent as an athlete. He went into the water. A 33-year-old white man carrying a shotgun told employees to clear white children off the beach. And then he shot Earl.

“The adult man came walking on the beach with a shotgun,” Loretta Halliburton, one of Earl’s classmates, told The Ledger in 2018, adding that her parents would not allow her to go to the beach that day. “Nobody stopped him — everybody stood around watching. And this man shot my classmate.”

Earl wound up in a wheelchair and eventually died from his wounds.

On the last day of school at Crystal Lake Middle School in Lakeland in 1967, about 10 parents showed up to display their displeasure about their children having to attend class with Black students.

"It was only about seven or eight of us who had integrated Crystal Lake,” said Precious Baker, a retired media executive. “The parents came dressed in the pointed hats and white robes and no one called the police. We had pennies thrown at us. Some of the teachers made sure we got on the school bus safely. No one called anyone to report it — that would’ve made headlines. About 10 of them dressed in their garb. I love police officers, but God knows I saw some black club sticks.”

In March 1969, the Klan began a recruiting campaign in Polk County, calling for schools to return to segregation and pointed to several incidents at Lake Wales schools — two violent — as a reason.

At Lake Wales High School, a Black student was told to shave off his mustache because it went against the school’s dress code, but he refused and was ordered to leave school. When he left, 46 of his Black friends walked out with him and held a demonstration in the school’s courtyard before returning to class.

Not long after that incident, two students — one white, one Black — got into a fistfight, which turned into a simmering feud. The Black young man hit the white student in the head with a piece of wood, sending the white student to the hospital and the Black student to jail. The Black students held another walkout, while parents took their children out of school for a few days for fear of a race war.

At the middle school, a Black female was suspended and arrested for kicking her female teacher. She was sent to the “juvenile home” in Bartow, from which she was already on probation for another offense.

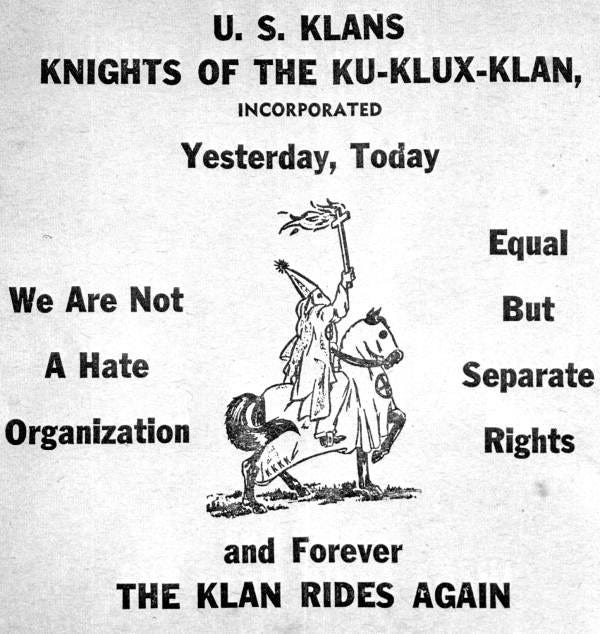

The Klan handed out fliers, which proclaimed, “These acts of violence (two incidents in the schools) and many more which we will not name at this time were committed by niggers. We must return to a segregated school system.”

At about this same time, Lake Wales resident John Paul Rogers was named Florida Klan Titan — the head of the state’s United Klans of America. Rogers lost his job at a barbershop after a newspaper article named him as the state's Klan leader.

In 1977, Rogers was invited to speak at a parents meeting at Tigertown to discuss integration.

Griffin Elementary School PTA president Van Newberry told The Ledger that he didn’t want to make race an issue of the desegregation order, but “we asked him because he has been studying this thing and knows a lot more about it than I do.”

Rogers encouraged about 150 parents to file a petition to keep their children from being bused. No Black parents attended the meeting.

Klan rallies common

In October 1969, about 30 robed Klansmen held a rally in Highland City, attended by 300 other people in street clothes in a large field off U.S. 98. Speakers included national Klan leaders, who promoted Alabama Gov. George Wallace’s new American Independent Party, among other things.

It was also held, in part, to help attract new members to the newly formed Bartow Klavern, “particularly young members ... who believe in God, white supremacy, the constitution, and the right to bear arms,” a security guard told a Ledger reporter at the time. “Join the Klan now because within two years, we’ll have an open season on niggers.”

And then they burned a 25-foot cross.

“The Klan is not a vigilante organization anymore. If we were, we wouldn’t walk around showing ourselves. The Klan’s not mean anymore.”

Four months later, a similar rally took place south of Lake Wales, where about 200 people heard national KKK Imperial Wizard Robert Shelton “condemn the federal Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Jews and integration,” according to a Ledger article. He called for a counter revolution.

State Klan leader Rogers spoke against the School Board for adhering to federally court-ordered integration, calling board members “weak-kneed, gutless, lowly cowards to condemn our children to integration.” He added that the Klan will sponsor private schools for white children. In May of that year, Rogers called for a boycott of Polk County Public Schools.

In the spring of 1971, signs began sprouting up on telephone poles and trees throughout the county, urging residents to “Join the Klan — Don’t be Half a Man.”

As the country geared up for the 1972 presidential election, Rogers said the Klan would become a political force, endorsing candidates who believed in their ideology. And some candidates, he said, were secret Klansmen.

The group also picketed businesses it didn’t think were appropriate, including an adult bookstore on U.S. Highway 27, south of Lake Wales.

On July 1, 1972, Rogers and the Klan held a parade in downtown Lakeland “to show our support of our boys in Vietnam and for additional membership,” Rogers said.

Rogers and Shelton appeared together at a public rally in Orlando along State Road 50, with Shelton predicting a revolution in the U.S. “Within the next four years” unless the political and economic climate changed. He talked about the violent confrontations over busing as Boston public schools integrated. But there were reports that the Klan was involved in that violence.

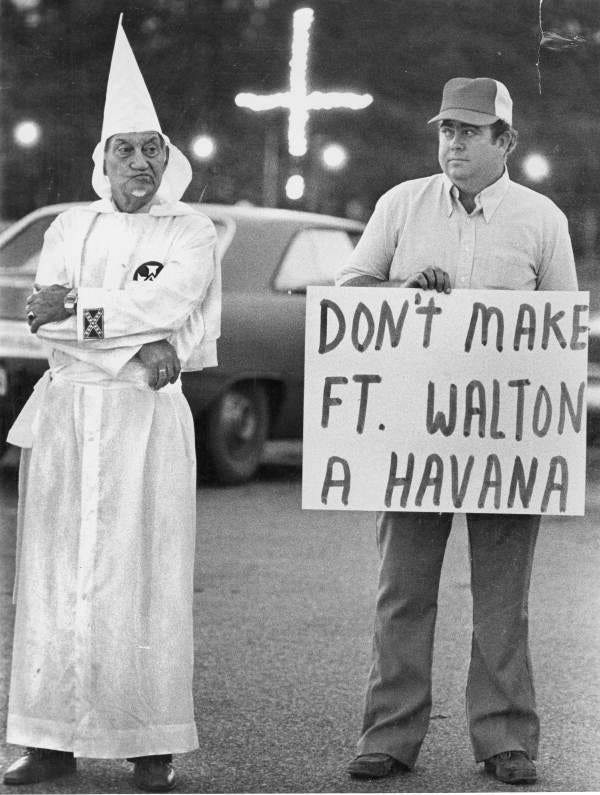

In 1975, they turned their recruitment up a notch by having robed Klansmen show up at area restaurants for a “coffee break” to recruit new members.

“We’re trying to let people see that the Klan is just working people, just like your neighbors or the kind that comes to do service work at your home,” Rogers said, sitting in a Lake Wales Whattaburger on State Road 60.

About 20 of the robed and hooded (but not masked) men also appeared at what was then known as Searstown and the old Lakeland Mall on Memorial Boulevard.

A Florida Southern College student from New York said, “I guess they deserve the freedom of choice everyone else has if they don’t bother anyone.”

A young woman with him said she was from South Carolina. “I’m used to it.”

“The Klan is not a vigilante organization anymore,” said Klansman Leon “Cue Ball” Walker. “If we were, we wouldn’t walk around showing ourselves. The Klan’s not mean anymore.”

In 1978 and 1979, more Klan rallies and cross burnings occurred in Lakeland and Lake Wales. One in 1978 was held on private property about one mile south of the U.S. 27/State Road 60 interchange, while another in January 1979 was held just outside the Lakeland city limits off South Florida Avenue.

“We’re still for white folks,” Rogers told The Ledger. At the rally, he talked about the problems of inflation, government regulation, moral decay, minority hiring and crime in the streets, but then veered into racial hatred. He referred to race riots in the late 1960s following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“Let them have the riots and let’s have some buck shot for some buck niggers,” Rogers told the all-white crowd.

'Prevalent during that time'

A month later, Fort Meade’s Black residents began protesting a lack of representation in city government and city officials deciding to spend a $277,000 federal grant on housing rehabilitation instead of new housing. In return, the Klan burned a cross in a primarily Black cemetery. Two men and three juveniles were arrested on charges of burning a cross in public. Two months later, the Klan held recruitment rallies in Fort Meade.

On April 21,1979, at least 20 crosses were burned along most of Polk County’s major roadways, including U.S. Highway 92 near Santa Fe High School, State Road 37 south of Lakeland, outside of Fort Meade’s city limits, State Road 33 near the interstate and every few miles along Interstate 4. At least two were spotted near Plant City and two men were arrested there. The burning crosses were anywhere from 3 to 6 feet high.

Kenneth Stephens, a military veteran, pastor and Southeastern University professor, said he remembered seeing the crosses that night.

“We were on some road — I can’t remember” which one, said Stephens, who was a teenager at the time. When asked how he felt, he said, “Scared, I mean just, if I’m going to be honest, just scared from what I knew about the Klan and the fact that here it is, during this time, I’m a teenager and that was prevalent during that time.”

In July 1979, a 9-foot by 4-foot cross was burned at Lake Parker Luxury Apartments, possibly because a white woman had several friends over for the evening, some of whom were Black. The apartment building manager said she received a phone call that night, with a voice on the other end saying, “Are you aware you have Blacks living with white girls in your apartments? If you don’t do something about it, we will. We are the United Klans of America.”

She said she also found a Ku Klux Klan pamphlet tucked under a windshield wiper. Rogers denied any involvement in the incident.

In August 1985, Al Smith, the first Black head football coach of a Polk County public school, saw a man run from his yard and found a small wooden cross burning in front of his home. Smith, who coached for Mulberry High School, grabbed a gun and called the sheriff’s department. But the deputy who responded failed to file a report about the incident and was suspended for one day.

In 1987, the letters KKK were found painted on a sidewalk and a large wooden cross placed in an all-Black apartment building in Winter Haven’s Jan Phyl Village.

“I didn’t think it could happen in 1987,” said Ruben Darby, president of the Winter Haven branch of the NAACP. “I’m just shook up.”

Another cross was burned that same year in the yard of a Black woman southwest of Winter Haven and KKK was spray-painted on her car and driveway. Five young men, 14 to 20 years old, were charged with that act. The Winter Haven City Commission quickly passed a resolution condemning cross burnings and the FBI opened an investigation. Two of the young men were later found guilty and served 60 and 30 days in jail.

In August 1988, Klansmen wearing what looked like short white bathrobes and hoods, rallied in Winter Haven’s Central Park. They were greeted with rocks, eggs and cans. Police broke up the meeting in which the Klansmen spoke to about 250 people. No one was injured and there were no arrests. About three dozen Winter Haven police officers and Polk County Sheriff’s deputies suited up in riot gear and armed themselves with shotguns as they marched in-between 25 Klansmen and anti-Klan protesters.

Lake Daisey Estates in Winter Haven was the site of violent acts against Black families in March 1991. Burned crosses were thrown onto the lawns of three residents and the home of one Black family was burned down. Two months later, copies of “The Klansman” newspaper were tossed onto driveways and lawns in that neighborhood.

City marches, meetings

In March 1977, Rogers petitioned Lakeland Mayor Charles Coleman, a Black man, to hold a Klan parade on March 26. Rogers had already been turned down for a permit by the police chief, who said it “was not an appropriate function,” nor would it be “in the best interest” of the city.

Coleman voted to deny the permit, but the city commission green-lighted it for April 2. About 75 robed Klansmen marched from the Lake Mirror Center through downtown Lakeland, with about 1,000 people watching. Coleman and the local chapter of the NAACP had urged residents to boycott the parade. Students from the University of South Florida followed the parade along sidewalks, yelling “KKK, Go Away!” It ended peacefully.

In April 1979, Rogers — dressed in a suit and tie — and more than a dozen robed and hooded Klansmen, including one who was told to put away a pistol and another carrying mace, showed up at a Dundee City Commission meeting to support a Dundee police officer. The officer, Sam Clark, had been investigated for firing his weapon during a chase of a Black man. A State Attorney investigation cleared the officer of any wrongdoing, but a local Black civil rights group wanted the officer to resign, which he did several months later.

Mayor Lonnie Adams adjourned the meeting rather than let Rogers speak.

The Klan applied for another permit from the city of Lakeland in the summer of 1979 to hold a rally at Joker Marchant Stadium and burn a cross, but City Manager Bob Youkey and Police Chief Herb Straley denied the permit for the cross burning. And then Rogers applied to hold a parade, which the city first denied, but then the city commission approved — if Rogers took out a $1 million insurance policy.

The Klan took the matter to federal court. Rogers said the cross burning was protected as religious freedom, since that is part of their religious observance. Florida law prohibits burning crosses on the property of another without their permission. Rogers called the $1 million insurance policy “ransom and blackmail.” A judge ruled in favor of Rogers and allowed the Klan parade to go forward without the insurance coverage.

About 100 members of the United Klans of America marched through Lakeland, while about 300 spectators watched without incident.

Shelton, the Klan’s national Imperial Wizard, said, “Our purpose is to wake the people of this country and I’m sick of all the advantages given to blacks and illegal aliens by our government.”

They marched again in Lakeland in December 1979.

In-fighting

In March 1980, three Polk County men and one from Hillsborough County were arrested for being uncooperative witnesses to a serious beating of two men at an Orange County KKK meeting. Ledger accounts say about 20 members of the Klan broke up a meeting of approximately 25 men in the second splinter Klan group with fists, rifles, shotguns and clubs. Two of the men beaten were hospitalized in serious condition. One of the men arrested was Sam Clark, the Dundee police officer who had been investigated for firing his gun during a police chase.

The victims identified Rogers and Lake Wales United Klans of America Exalted Cyclops Raymond Turner as being their assailants. Both surrendered to Orange County Sheriff’s Office deputies and were charged with three counts of aggravated battery. Both said they were at a business meeting with three other people at the time of the incident. A jury found both men not guilty and within two years both ran for public office.

Law enforcement and Klan

A furor arose in 1985 when Sheriff Dan Daniels hired two men who admitted during a pre-hiring polygraph test to being former members of the Klan. Sgts. Billy Hyatt and Pete Peterson had been officers with the Lakeland Police Department before joining PCSO. Hyatt claimed he was working undercover, which LPD officials said was untrue, while Peterson said the Klan had helped him through a difficult time in his life and so he joined.

Hyatt and Peterson also admitted to illegal searches without warrants, but were later cleared of wrongdoing by a State Attorney investigation. Daniels created a new policy at the department to rid its ranks of any known Klansmen.

After 25 months of investigations by the State Attorney and a grand jury, a sealed report was sent to the governor’s office on Jan. 16, 1987, and four days later, Daniels resigned from the office he held for two years.

Bankrupt – but not gone

In 1988, the national United Klans group went bankrupt after the Southern Poverty Law Center in Alabama won a $7 million judgment from the Klan for the family of 19-year-old Michael Donald, who had been lynched in Alabama several years earlier.

The United Klans' assets were seized nationwide, including property in Lake Wales near Mountain Lake Cut-Off Road.

But two years later the Klan was back. A group known as The Dixie Knights held a rally in Lake Wales. James Austin, Lake Wales’ first Black mayor, urged residents to simply “ignore them like a bunch of ignorant stupid people who are trying to turn the clock back.”

In 1990, the Klan began patrolling Polk County streets for evidence of drug dealers at the height of the crack cocaine epidemic. Lakeland Police Capt. Wayne Roddenberry said at the time that he thought the “Krush Krack Kocaine” campaign was headed up by two Kathleen area residents, Lloyd Spivey and George Kirkland. Spivey described himself as the Grand Dragon of the Florida Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, while Kirkland said he was the kleagle of a splinter group called the Original Knights of the KKK. At one point, they were questioned for impersonating police officers. They also operated near Eagle Lake.

In February of that year, Spivey, who had been in and out of prison, was arrested for spousal battery and, two months later, the sexual assault of a 16-year-old girl. According to a sheriff’s department investigator, Spivey was recruiting the girl to be in the Klan and made her sign an oath that she would be willing to “steal, kill and have sex with other Klan members if necessary.” He was found guilty and sentenced to 30 years in prison, where he died.

According to a 1992 Southern Poverty Law Center report, Klan activity was documented in Auburndale and Lakeland. The next year, local law enforcement officials who monitor gang and Klan activities said there were active groups in the county, but no criminal activity had been linked to them.

In 1994, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan held a rally in Munn Park, near the Confederate monument. About a dozen Klansmen took part in the rally, while about 30 protesters walked around them, carrying signs and praying.

Half a dozen Ku Klux Klan members protested across from Auburndale High School on Aug. 18, 1995, to support a student’s right to wear a T-shirt with the Confederate flag. Polk County Sheriff's deputies ordered them to leave the area after they arrested one Klansman.

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center in 2009, the Fraternal White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan were found in Highland City, Lakeland and Plant City.

Former Grand Dragon Rogers is still a resident of Lake Wales and active in politics. In the ’90s, Rogers ran unsuccessfully for Florida secretary of state and the state House. Rogers served for six years on the city’s Zoning Board of Appeals.

"I treated everybody fair," he said. "I’ll do the same thing on the City Commission. I don’t let my personal views interfere with the basics."

“In light of everything happening right now, I think it’s best if I don’t say anything."

In 2008, he won a seat on Lake Wales City Commission, but in 2011, he lost a bid for mayor, with his opponent receiving 84% of the vote.

When reached recently for this story, Rogers declined to comment when asked if he still holds the same views about white supremacy after more than five decades.

“In light of everything happening right now, I think it’s best if I don’t say anything,” Rogers said in a brief phone call.

Ledger reporter Kimberly C. Moore can be reached at kmoore@theledger.com or 863-802-7514. Follow her on Twitter at @KMooreTheLedger.

Black In Polk Series

• Sunday: Polk's Black history

• Monday: Slave descendants

• Sunday: Forgiveness and grace

• Today: Ku Klux Klan

• Thursday: County government

• Friday: Law enforcement

• Saturday: Civil Rights movement