“If there ever was a moment that showed us the need for all people to be able to get health care regardless of their income, this is that moment,” Bernie Sanders tweeted on Thursday afternoon. In response to the coronavirus pandemic this month, many journalists have similarly argued that our underpreparedness for the coronavirus is proof that safety-net programs like universal health care are not just humane but smart. “Medicare-for-all is usually presented as a moral argument,” wrote Helaine Olen in the Washington Post a few weeks ago. “But this situation isn’t simply immoral”—it leaves us all hurting.

This emerging consensus on the left reminded me of something I read in historian Nancy Tomes’ The Gospel of Germs, about the way late-19th and early-20th-century American culture responded to the revelation that germs cause disease. Some Progressive Era reformers, arguing for the financing of social programs in American cities, leveraged their new understanding of germ theory to try to convince elites to care more about the health of the poor. In his 1895 article “The Microbe as a Social Leveller,” Cyrus Edson, a physician and New York City health commissioner, made the case for what he called “the socialism of the microbe,” the idea that to care for others was also to protect oneself: “It is not only in material things that the prosperity of each is dependent on that of his fellows. Disease binds the human race together as with an unbreakable chain.”

As another infectious disease reshapes American life, is now the time for this century-old argument to finally convince Americans that collective health security benefits everyone? I called up Beatrix Hoffman, a historian who has written about health care social movements in books including The Wages of Sickness: The Politics of Health Insurance in Progressive America and Health Care for Some: Rights and Rationing in the United States Since 1930, to talk about the precedents. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Slate: I’ve seen a lot of people online making the point that the coronavirus is a good argument for social programs like “Medicare for All” and paid sick leave. I was very curious to know more about other times this argument might have been made, in connection with other infectious diseases.

Beatrix Hoffman: Yes, what you’re describing has come up a lot in the last century. But when you ask me, has the United States ever expanded services based on this argument that epidemics can affect everyone? My answer is, the argument has been made, but it has not been successful. There have been a few times when it’s been partially successful, but it’s mostly been a losing argument, because of our political culture and the forces against universalism.

But yes, in the Progressive Era, this argument was floated a lot by people proposing health coverage and paid sick leave. This was the movement for compulsory health insurance, which overlapped with the public health movement, but was more in the spirit of some of the Progressive Era reforms that were successful, like workmen’s compensation.

It’s so interesting that this is coming to the fore again, because the compulsory health insurance movement was actually more about sick pay than it was about health care. That’s because early-20th-century medical care just wasn’t all that expensive, and it wasn’t all that effective. So the main concern of workers—and this was a movement by, and on behalf of, working people—was that when they got sick, they didn’t get paid. Sickness could lead to poverty; sickness was terrifying for that reason, as well as the physical reason.

Were they making the argument to elites that they should care—if not out of charity for their fellow man, then at least out of self-protection?

Yes, people did make that argument. There was something called National Negro Health Week, a public health movement spearheaded mostly by African American women in the South around the turn of the century. They had a slogan: “Germs know no color line.” The argument was, OK, you don’t care about us, but if our communities get sick, then yes, it can spread to more affluent communities. It was a very calculated way for them to bring in the self-interest of elites, to get them to provide more funding for sewer and water facilities in poor neighborhoods.

Oh yes! I read this article about sanitation in Atlanta, by Stuart Galishoff, that had that slogan as its title: “Germs Know No Color Line: Black Health and Public Policy in Atlanta, 1900–1918.”

Yes. There’s also a book called Sick and Tired of Being Sick And Tired, by Susan L. Smith, that’s about these black women’s health movements in the first half of the century.

So is this what you were thinking of when you said that sometimes people achieve partial success? Because if I was reading the Galishoff article correctly, that argument was successful in getting Atlanta to fund sanitation in poor neighborhoods.

Yes, that’s one example. In the early 20th century, the situation with Typhoid Mary also led to a new regime of restaurant inspection.

But of course, Typhoid Mary was different because she wanted to go to work and she was punished for doing so. The majority of food service workers, of course, didn’t have that choice. They may have preferred to stay home when sick, but they just simply couldn’t.

Then, as now, people arguing against sick pay would say, “These workers are just malingering.” The reformers arguing for paid sick leave would make the argument that without it, workers would do something called “the malingering of health”—that they’d pretend to be healthy, even though they were clearly sick, and go to work and infect middle-class people who were consumers.

So they tried that argument! But it wasn’t strong enough to win the debate.

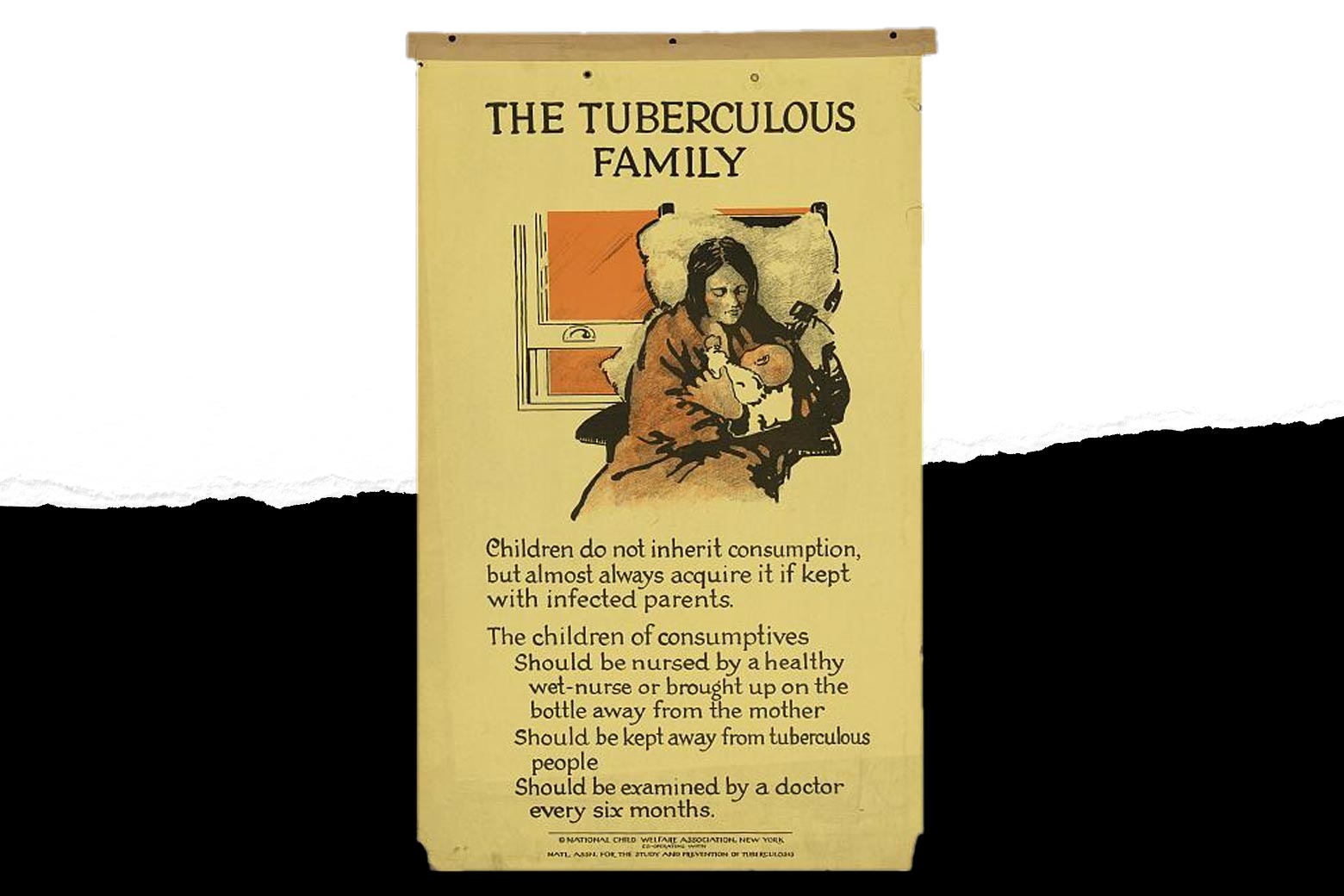

The National Consumers League is another example—an organization that really scared middle-class people about the idea that women who had tuberculosis might spread it to them when they did their laundry. That didn’t lead to reforms for the workers.

This, of course, is like the famous Upton Sinclair quote about aiming to hit the public in the heart and instead hitting them in the stomach. Those readers were more concerned about what they were ingesting than the conditions of the workers who were producing the food.

So this debate over compulsory health insurance was happening in the ’20s and ’30s?

No, the teens—really, 1915 through 1920. It was a state-level debate that came close to passage in New York state and was debated in several other states. There was a referendum in California, which failed.

Did the 1918–19 influenza epidemic affect that conversation at all?

It’s such a good question. I had it the whole time I was writing! I was amazed at how few references there were to the flu. I think it’s partly what I said earlier—the fact that medical care could do nothing for that influenza. Nursing care could do something. I did see some arguments to that effect, because the proposal in New York for compulsory health insurance would have included nursing care. But on the whole, there was just a whole lot more discussion of tuberculosis than of influenza.

I don’t know why. Maybe it was because the influenza epidemic was covered up—omitted, for example, from the Army’s official medical history of the war—and people were really reluctant to talk about it. That’s a whole other set of research questions there.

I read a lot about flu last year around the anniversary of the pandemic, and people are curious now, like, “What effect did the 1918–19 flu have on people after it was all over?” And I think the answer is “Not as much as you would expect!” It seems historians agree that people really wanted to move on.

Yes, it’s complicated. Some instances of official cover-up, but then also more complicated issues, where it was so cognitively dissonant that this had happened. The scale of loss had been so catastrophic that people were almost in shock. It seemed so un-American! Like, “We won the war. Let’s focus on that instead.”

I want to add one more thing about the fact that we don’t talk very much about collective health in this country. Around 1920, there was a strict separation between public health and medical care in the United States that was very deliberate and I think added to our inability to pull together all of the resources we need. The American Medical Association worked really hard to make sure that the mandate of public health was different from what physicians did. Any attempt by public health agencies to actually provide care as opposed to diagnosis was, they said, unfair competition, and they succeeded in eliminating most publicly funded provision of care.

Did you see the quote from CDC Director Robert Redfield yesterday? That they don’t want the government to be testing for the coronavirus, because they don’t want to get between the patient and the doctor?

That’s a perfect example, yeah.

You must be going crazy, seeing all these things you’ve researched, in the news.

Yes, we’re seeing all the consequences of our historical choices now.

Do you have any hope or advice for people who want to use this moment to make an argument for something like “Medicare For All” or paid sick leave? Or are you pretty grim about it?

I’m concerned that there will be some emergency measures, like delivering the test for free, but when this is over, are we just going to go back to having deductibles and copayments be a barrier to getting basic health care for the majority of people?

But at least we’ve been talking about it more than we ever have in my memory—not just health care but paid sick leave. I just hope that this conversation will lead to some really lasting changes. Because now we’re seeing that the lack of universal health care is deadly, and the right to stay home for a few days and not lose your paycheck is a public health issue too.