This story was produced as part of the Democracy Day journalism collaborative, a nationwide effort to shine a light on the threats and opportunities facing American democracy. Read more at usdemocracyday.org.

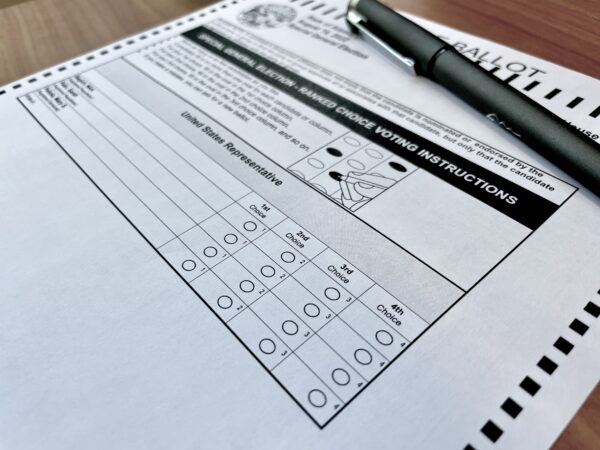

Most people who used ranked choice voting for the first time this August thought the process was simple according to a survey commissioned by Alaskans for Better Elections. Most had learned about the process through extensive outreach efforts across the state like mailings from the Division of Elections, social media campaigns, and family and friends. Despite understanding how it works, many voters we spoke with still had questions about why we have ranked choice voting in the first place. Here’s some background on RCV in Alaska and beyond.

Why does Alaska use ranked choice voting?

Alaskans passed Ballot Measure 2 in 2020, which shifted the state to the new voting system. It passed narrowly, with a total of 50.55% of the vote, a margin of 3,781 votes. The 2020 ballots were hand-counted and the election results confirmed during an audit ordered by Lt. Gov. Kevin Meyer in December of 2020.

Ballot Measure 2 created the non-partisan pick one primary and the four-candidate ranked choice voting general election. It also included provisions related to campaign finance transparency. It required groups who are campaigning on behalf of or against candidates, but not ballot measures, to disclose if most of their funding came from a source outside of Alaska.

Much of the campaign to pass the ballot measure was funded by sources from outside of the state. More than $2.8 million came from the Action Now Initiative, a nonpartisan group based in Texas focused on criminal justice, healthcare, and democracy reform and funded by Arnold Ventures. Another nearly $2.8 million came from Unite America, a group based in Colorado that aims to “bridge the growing partisan divide and foster a more representative and functional government.”

Is ranked choice voting new?

In Alaska, yes. But not in the rest of the world. The Irish have used a similar system since 1919. In Australia, preferential voting, which requires voters to rank candidates, began in 1918. In both of these nations, voters rank far more than four candidates. In the United States, 53 cities use it, including Arden, Delaware which started it in the early 20th century. Maine is the only other state that has ranked choice voting. They switched to that system in 2018 after voters approved the idea as a ballot initiative in 2016. (Want to learn more about what ranking candidates and hand counting ballots is like in Ireland? WNYC’s Radiolab has a whole episode on RCV from 2018.)

RELATED: Practice Ranked Choice Voting Before the November Election

What does the research say about RCV?

The goals of ranked choice voting include increasing voter participation, increasing civility in campaigns, and creating a more representative democracy. Most research in the United States supports these claims to a degree.

For example, one study found that RCV didn’t increase overall voter turnout, but it did increase youth voter turnout. Using survey data from young voters, the researchers found that in RCV elections, candidates and campaigns reached out more to young voters and turnout increased. A 2011 dissertation asserts that ranked choice voting in San Francisco has increased the diversity of locally elected officials and increased voter turnout for communities of color, though the author notes she was working with a small amount of data.

Multiple studies also support that RCV increases campaign civility. A survey of voters in cities that use ranked voting versus the more common plurality voting showed that they were more satisfied with the elections and that candidates were less negative. A 2021 examination of campaign tweets and newspaper articles showed that candidates in cities that use RCV were less negative and interacted with each other more.

An unpublished working paper on the shift to ranked choice in Minneapolis and St. Paul showed that it increased voter turnout for the mayoral election, especially in areas with higher poverty rates. An analysis of mayoral debates in the same study found that the candidates were more civil toward each other.

RepresentWomen is a nonpartisan organization focused on getting more women into political office. Their data shows that communities that use RCV elect more female officials.

Maine is the only other state where RCV is used beyond individual cities or counties. A researcher at MIT looked at the effect of RCV after its first use in 2018. He found that it did not increase campaign civility but that people were more likely to vote for third-party candidates. Another survey of municipal clerks in Maine after the 2018 election found that they were not enthusiastic about implementing the new system and that support for it varied depending on party lines.

Will we always have RCV from here on out?

That depends. The ballot initiative passed in 2020. Because two years have passed, the Legislature can vote to repeal the law. They can also amend it.

This story stems directly from input by voters like you. Alaska Public Media reached out to voters across the state both online and in-person to find out what you want to know this election season. Learn more about our voter outreach and our collaboration with other local news organizations here.

Find other elections coverage and voter resources at alaskapublic.org/elections. Easily compare candidates with our new interactive tool!

Want to know the story behind the story? Subscribe to Washington Correspondent Liz Ruskin’s newsletter, Alaska At-Large.

Remember: Early voting locations are already open. You can still get an absentee ballot via fax or online delivery. Have other questions about the election? Get answers through our partners at KTOO by filling out the box below.

Anne Hillman is the engagement editor for a special elections-focused project at Alaska Public Media. She also runs Mental Health Mosaics, a project of Out North that uses art, podcasts, poetry, and creativity to explore mental health and foster deeper conversations around the topic. Reach her at ahillman@alaskapublic.org.