Newsletter Signup

Stay up to date on all the latest news from Boston.com

In Massachusetts, black bears are seemingly everywhere. This year, bears have been spotted cooling off in a Pepperell koi pond, near a summer day camp in Wilmington, and on a major avenue in Lowell. One animal was even injured while trying to cross Route 495 in Middleborough before officials had to euthanize it.

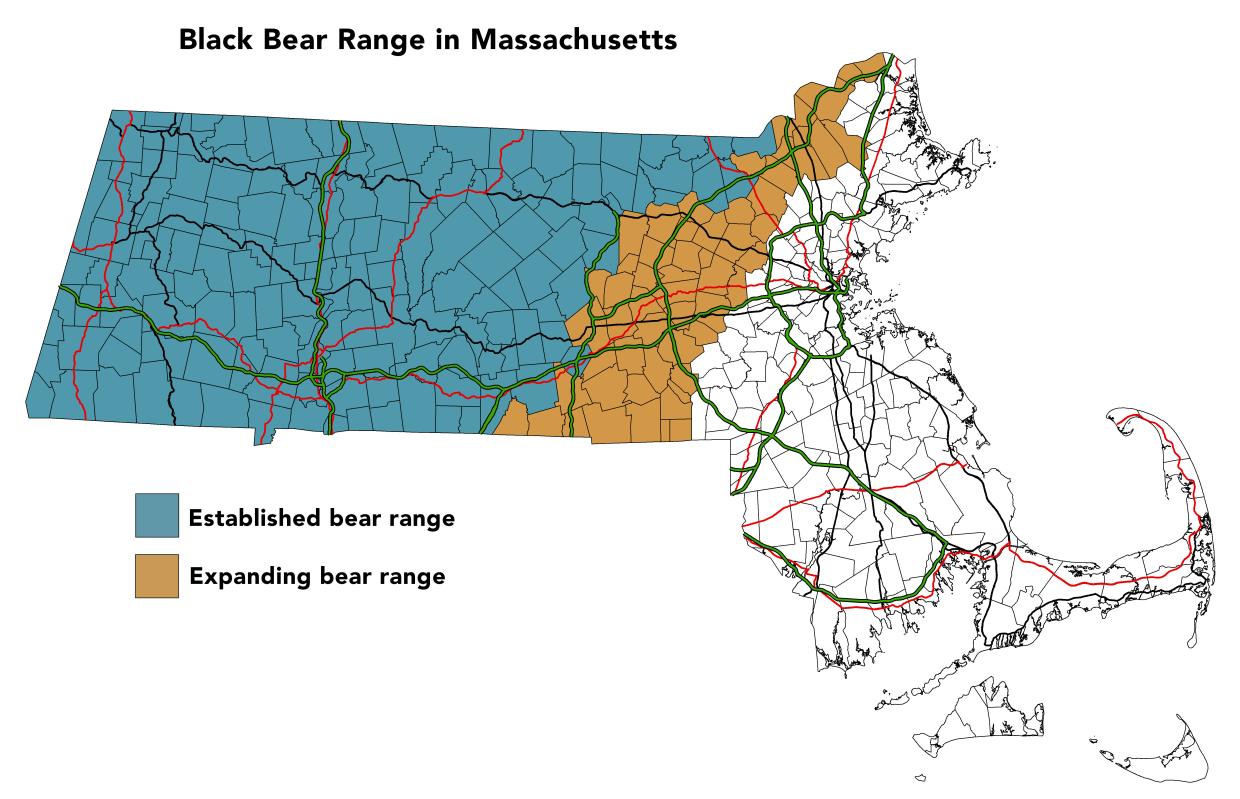

These are not random occurrences, but evidence of something that scientists have been tracking for years: a resurgence in the population numbers of Massachusetts black bears, and a notable expansion of their range eastward.

Due to deforestation and wide-open hunting laws, black bears were rare in the state throughout the 1800s and the early parts of the 1900s. Even into the 1970s black bears only existed as a small and isolated population in the Berkshire Mountains. In 1952, new laws made it illegal to kill the creatures except during regulated hunting seasons and by those with a license. This change, combined with regrowth of forests and various conservation efforts, has fueled a black bear boom.

The state government estimates that there are around 4,500 bears in the state. This number is rising at a rate of about 8% a year. according to Mass Audubon. For years, the established black bear range in Massachusetts only reached the Worcester area. Now, state officials say the range has expanded all the way to towns like Concord and Lincoln.

Despite these notable changes, researchers are still lacking something crucial: an up-to-date, wide-ranging population and density estimate. This is required for the proper management of black bears, and for informing the public about how to deal with their furry neighbors.

Enter MassBears, a project led by researchers affiliated with MassWildlife, Amherst College, UMass Amherst, and the United States Geological Survey. This study aims to survey black bears using hair snares and molecular science. The goal is to understand how bear population numbers change depending on land cover types and differing levels of human influence. In the end, the information gathered will be used to create a new comprehensive management plan for Massachusetts black bears.

To achieve these goals, MassBears is also relying on the public. Information about bear sightings can be entered into the group’s website.

Thea Kristensen, a principal investigator on the project and a Laboratory coordinator at Amherst College believes that this work can go beyond numbers on a spreadsheet and towards a more rewarding relationship between humans and bears.

“Bears are a really dynamic species and people are always excited about them, or nervous about them, so getting the public thinking about this and talking to us about it is a really positive step towards coexisting,” she said.

The last density study like this was conducted in 1993, according to the MassBears website, so Kristensen and her colleagues have their work cut out for them.

It’s hard work, said Elizabeth Zhang. As a junior at Amherst College working with Kristensen, Zhang was tasked with checking hair traps and collecting samples to bring back and analyze in a lab. Through two distinct field seasons, students and researchers dealt with record summer temperatures and difficult terrain to collect their samples.

But the results have been worth it, Zhang said, especially regarding information she’s learned about bears in eastern regions with a higher human population density.

“Increasingly, what we’re seeing and suspecting is that these bears in the east, in areas that have a higher human density, are more likely to approach human homes,” she said.

Typically, Kristensen said, black bears are unlikely to approach humans. But this is changing in the eastern edge of their Massachusetts range, partly because of the abundance of anthropogenic, or human-originating, food sources. Kristensen credits UMass researcher Kathy Zeller’s work for showing that bears in rural areas of the state avoid humans more than their counterparts in the east.

Although researchers know that black bear ranges are expanding generally, work done by the MassBears team will help pinpoint which specific communities could see more bear activity in the near future. Most residents won’t be used to bear encounters, Kristensen said, so public outreach will be necessary to prepare people and tell them how to avoid dangerous situations.

“A lot of people are really scared of bears, and when there’s any sort of negative interaction it can get blown out of proportion. It’s actually extremely rare to have negative interactions with black bears… they’re not interested in eating people at all.” Kristensen said.

Black bears are opportunistic omnivores, meaning that they can eat meat but do not hunt and track prey. If one encounters a bear, the best thing to do is to make loud noises and try to look large, Kristensen said. A bear’s first instinct when encountering something unusual is to leave, according to MassWildlife. A major safety tip is to avoid running away from the bear. Instead, it is best to back away slowly.

Luckily, researchers have developed ways of tracking bears without having to get up close and personal with them. MassBears uses a non-invasive survey technique called a hair corral.

These consist of two strands of barbed wire wrapped around a circle of three to five trees. The wires are placed about knee-high and calf-high. Something with a scent detectable to bears is hung in the middle of the circle. As bears pass through the area, they are drawn to the scent and cross the wires to investigate. The wires capture hair samples, which are then collected by workers.

As part of the MassBears project, teams of researchers from MassWildlife set up hair corrals on both sides of the Connecticut River in 2019 and 2021, Kristensen said. The corrals only stay up during the field season, and are taken down at the end of the summer.

Hair corrals are much more preferable than culvert traps, Kristensen said, which use bait to lure bears into a small area before a door automatically swings shut behind them.

“[Hair corrals are] an extremely helpful method. Think about bears and how big they are and how challenging they might be to work with. To get a population estimate with them would be really challenging if we’re relying on culvert traps to capture and mark bears. There’s a massive amount of effort needed to do this.” she said.

While hair corrals are the main method used by MassBear researchers, some scientists affiliated with UMass and MassWildlife are tracking certain bears using collars. Important information can also come from sighting reports from the public and from data collected by bear hunters.

In Massachusetts, hunters are permitted to take down black bears during certain times in September, November, and December. The state asks that hunters who kill a bear submit tooth and hair samples for further research.

Kristensen acknowledged that the topic of hunting can be divisive, but in Massachusetts, it is a helpful practice in managing population numbers.

“In terms of managing the bear population, I’ve talked to bear biologists all over the country and they definitely have seen that it can be helpful to allow that to happen within a state because the numbers of bears can get really high,” she said.

Ultimately, she added, the work being done as a part of the MassBears project is important because it will ideally change the way members of the public perceive black bears.

“I want to help people feel like they can comfortably coexist with bears, to not have that reaction of ‘oh my gosh I’m so scared of this species,’ but instead say ‘ok we can make this work,’” Kristensen said. “That’s a major passion for me.”

Stay up to date on all the latest news from Boston.com

Stay up to date with everything Boston. Receive the latest news and breaking updates, straight from our newsroom to your inbox.

Conversation

This discussion has ended. Please join elsewhere on Boston.com