The IPO outlook in one word

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Craig Coben is a former senior investment banker at Bank of America, where he served most recently as co-head of global capital markets for the Asia-Pacific region.

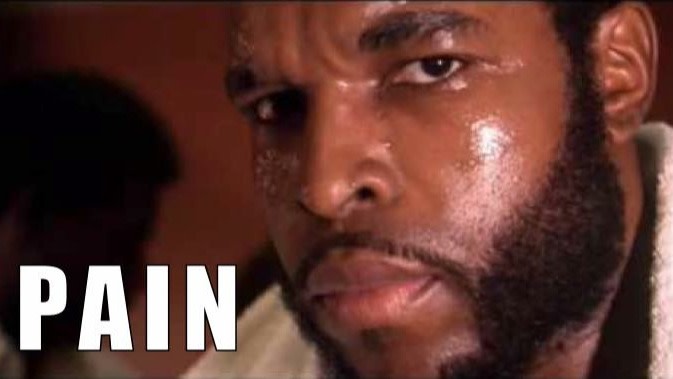

In Rocky III a broadcast journalist asks Clubber Lang (memorably played by Mr. T) what his prediction was for his upcoming fight against Rocky Balboa. “Prediction?” asks Lang, who then looks into the camera. “Pain.” That is also my forecast for initial public offerings in 2023.

Listings are coming off their worst year this century. It has been nothing short of carnage for issuers, investors and underwriters. Volumes have collapsed around the world, and the 2020 and 2021 vintage of IPOs are mostly trading well below their initial offer price.

Yes, Porsche’s recent IPO has traded well, but the supply of stock on offer was carefully limited. Meanwhile, London’s largest IPO of the year, Ithaca Energy, priced at the bottom of the range earlier this month and is now around 20 per cent below its IPO price. And hopes for an IPO rebound in 2023 look optimistic to me.

The physicist Niels Bohr is reputed to have said: “Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future.” Nevertheless, it is important to make some kind of forecast about the IPO market for two reasons.

First, companies need to plan. An IPO cannot be launched opportunistically. It requires months of preparation and seasoning, with substantial legal and administrative costs. It is also a huge distraction of management from their day-to-day job of running the business. The UK law firm Mischcon de Reya spent nearly £12mn to prepare for an IPO that has been put on hold. Like European conscript armies on the eve of the first world war, mobilisation is so costly and time-consuming that you risk feeling committed to proceeding if you advance far enough in your preparations, even if the circumstances aren’t ideal.

Second, the IPO service “ecosystem” needs to plan. IPOs require a lot of bankers, attorneys, auditors and other experts. The working group list on any IPO is always long with hundreds of names on it. These various firms have to figure out their staffing needs for what is lumpy but lucrative — and labour-intensive — business.

The pain does not arise because markets have crashed. In fact, current valuations remain elevated, even if they’ve corrected from the nosebleed levels of 2021. Over the past six months, the S&P 500 has actually risen slightly, and today it is trading at around April 2021 levels. Volatility has also returned to manageably moderate levels.

Rather, the dour IPO market outlook — at least for the first half of the year — has to do with the way investors approach valuing most IPOs.

When a company goes public, investors latch on to the sales and earnings numbers (whether net income or ebitda), which the research analysts forecast, usually with the help of management’s guidance. The projections are pivotal for the valuation. A company going public in, say, March 2023 will be roughly priced based on the valuation of listed peers and their forecasted full-year 2023 earnings. So if public widget companies are trading on average at 15 times their expected 2023 earnings, then a new widget company will (all things equal) command the same multiple, less a 10-20% so-called IPO discount.

As effects of monetary tightening feed through and economies slow, sales and earnings will probably taper off. If an IPO launches in the first half of 2023, investors and analysts will be using trough figures as their starting point. That depresses the valuation and makes it an inopportune time to IPO. Management may conclude that it is better to wait to launch on the basis of 2024 projections. By then, economies and earnings will hopefully have recovered.

It is never certain at what stage investors shift from pricing off 2023 forecasts to 2024 forecasts — it really depends on the industry and factors such as order-book visibility — but roughly speaking, the focus shifts to 2024 projections once you are in the third or fourth quarter of 2023. So even if the stock market valuation of their peers holds up, it might be better for most companies to defer IPO plans to the second half of 2023 at the earliest to take advantage of more flattering numbers as the basis for a valuation discussion with the market. And 2024 often make the most sense.

Other factors will also slow down IPO volumes in 2023. The IPO market thrives most when investors crave the taste of high-growth stocks, often with a new-age bent. But technology and life sciences stocks have been absolutely battered this year, speculative “concept” stocks have been trashed, and the sizzling appetite for high-risk, early-stage companies of 2020-2021 has curdled into the capital markets equivalent of nausea.

Around 70 per cent of the current IPO backlog in the US is said to be in technology, healthcare and consumer assets — precisely those sectors that are the most out of favour right now.

To make matters worse, many unicorns and decacorns (private companies valued at over $1bn and $10bn respectively) have raised private money at valuations that will be unachievable in the public markets for a looong time. So-called “down rounds” are possible at IPO time, but they look bad, may trigger anti-dilution provisions to the detriment of management and employees, and could force investors from private fundraisings to mark down their investments, possibly exposing these money managers to redemptions and ridicule. The default decision is therefore to wait to see if valuations can recover and spare everyone’s blushes (if possible).

Higher interest rates and wider spreads will affect the IPO in other ways, too. Private equity had, for example, taken advantage of low interest rates in years past to pile leverage on to the assets they control in order to drive up returns.

As a general matter, public investors have less tolerance for leverage than private equity because they can’t supervise performance as closely. But if a company with, say, 5-6 times leverage ratio (net debt-to-ebitda) goes public, it will have to issue a lot of new shares to reach a more market-acceptable 2.5-3 times leverage ratio.

Such a large slug of new shares will crowd out the ability of the private equity firm to sell many of its own shares. Moreover, any refinancing will come at much less favourable terms. So the inclination will be to defer any IPO until operational cash flows can organically reduce leverage and to leave in place financing packages secured in happier times.

One ray of sunshine may be spin-offs like September’s Porsche IPO. With share prices treading water and in the absence of M&A, public company CEOs are coming under pressure to find ways to generate returns. Spin-off IPOs allow companies to unlock value and reduce any discount from a sum-of-the-parts valuation — and thus to get ahead of any activist shareholder campaign that could force management’s hand.

These carve-outs also have the benefit of investor familiarity: shareholders will often have studied and modelled these businesses, and so the task of investor education at IPO will be that much smoother. And for the offering to be a success it just needs to create incremental value versus the status quo of leaving the business within the larger concern, not to meet the return yardstick of a venture capitalist or private equity firm.

Overall, though, the IPO will be sluggish at best and comatose at worst for at least the first half of 2023.

Comments