This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Quantum simulator enables first microscopic observation of charge carriers pairing

Using a quantum simulator, researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics (MPQ) have observed pairs of charge carriers that may be responsible for the resistance-free transport of electric current in high-temperature superconductors. So far, the exact physical mechanisms in these complex materials are still largely unknown.

Theories assume that the cause for the pair formation and thus for the phenomenon of superconductivity lies in magnetic forces. The team in Garching has now for the first time been able to demonstrate pairs that are formed this way. Their experiment was based on a lattice-like arrangement of cold atoms, as well as on a tricky suppression of the movement of free charge carriers. The researchers report on their results in the journal Nature.

Since the discovery of high-temperature superconductors almost 40 years ago, scientists have been trying to track down their fundamental quantum-physical mechanisms. But the complex materials still pose mysteries. The new findings of a team in the Quantum Many-Body Systems Department at MPQ in Garching now provide new microscopic insight into processes that may underlie these so-called unconventional superconductors.

Crucial to any kind of superconductivity is the formation of tightly linked pairs of charge carriers—electrons or holes, as electrons vacancies are called. "The reason for this lies in quantum mechanics," explains MPQ physicist Sarah Hirthe. Each electron or hole carries a half-integer spin—a quantum physical quantity that can be imagined as a measure of a particle's internal rotation. Atoms also have a spin. For quantum statistical reasons, however, only particles with an integer spin can move through a crystal lattice without resistance under certain conditions. "Therefore, electrons or holes have to pair up to do this," says Hirthe.

In conventional superconductors, lattice vibrations called phonons help with pairing. In non-conventional superconductors, on the other hand, a different mechanism is at work—but the question of which one it is has remained unanswered until now. "In a widely accepted theory, indirect magnetic forces play a crucial role," Sarah Hirthe reports. "But this could not be confirmed in experiments so far."

Solid state model spiked with holes

To better understand the processes in such materials, the researchers used a quantum simulator: a kind of quantum computer that recreates physical systems. To do this, they arranged ultracold atoms in a vacuum with laser light in such a way that they simulate the electrons in a simplified solid-state model. In the process, the spins of the atoms arranged themselves with alternating directions: an antiferromagnetic structure was created, which is characteristic of many high-temperature superconductors—and stabilized by magnetic interactions. The team then doped this model by reducing the number of atoms in the system. In that way, holes emerged into the lattice-like structure.

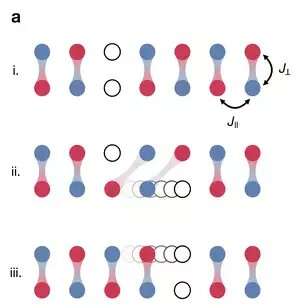

The team at MPQ now could show that the magnetic forces indeed lead to pairs. To achieve this, they used an experimental trick. "Moving charge carriers in a material like high-temperature superconductors are subject to a competition of different forces," explains Hirthe.

On the one hand, they have the urge to spread out, i.e. to be everywhere at the same time. This gives them an energetic advantage. On the other hand, magnetic interactions ensure a regular arrangement of the spin states of atoms, electrons and holes—and presumably also the formation of charge carrier pairs. However, "the competition of forces has so far prevented us from observing such pairs microscopically," says Timon Hilker, leader of the research group. "That's why we had the idea of preventing the disruptive movement of the charge carriers in one spatial direction."

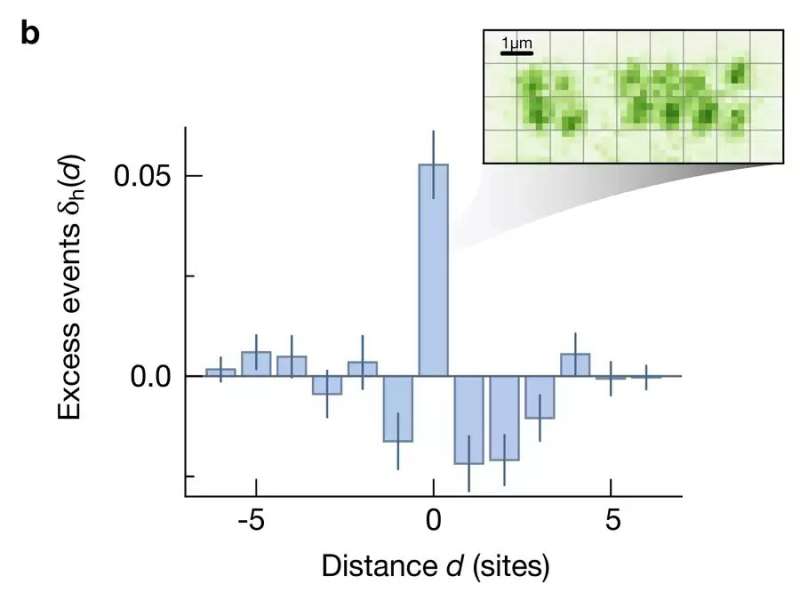

A close look through the quantum gas microscope

This way, the magnetic forces were, to a large extent, undisturbed. The result: holes that came close to each other formed the expected pairs. To observe such pairing, the team used a quantum gas microscope—a device with which quantum mechanical processes can be followed in detail. Not only were the hole pairs revealed, but the relative arrangement of the pairs was also observed, suggesting repulsive forces between them. The team reports on their work in the scientific journal Nature.

"The results underline the idea that the loss of electrical resistance in non-conventional superconductors is caused by magnetic forces," says Prof Immanuel Bloch, Director at MPQ and Head of the Quantum Many-Body Systems Division. "This leads to a better understanding of these extraordinary materials and shows a new way of how stable hole pairs can form even at very high temperatures, potentially significantly increasing the critical temperature of superconductors."

The researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics now plan new experiments on more complex models in which large two-dimensional arrays of atoms are connected. Such larger systems will hopefully create more hole pairs and allow for the observation of their motion through the lattice: the transport of electric current without resistance due to superconductivity.

More information: Sarah Hirthe et al, Magnetically mediated hole pairing in fermionic ladders of ultracold atoms, Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-05437-y

Journal information: Nature

Provided by Max Planck Society