Estimated read time: 7-8 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Aaron Skonnard was just eight or nine years old when his father walked in the door of their modest Seattle home with one of the first Apple computers.

“We weren’t affluent. We really didn’t have any business owning a computer,” Skonnard said. “Somehow my dad scrambled and scraped together enough to get one. … He had a sense that this was going to change the world.”

Skonnard and his father would spend the next several years together, messing around with the computer in the basement and teaching themselves to code. A few decades later, Skonnard would found Pluralsight — a tech education company lauded as one of Utah’s rare unicorns before it went public this year with an offering over $350 million.

Skonnard credits those moments in the basement with his father as some of the most powerful in his life. Learning to program opened a world of possibilities and marked a path for his future, he said. Yet, Skonnard is worried that other children aren’t getting the same type of opportunity and education — especially in Utah.

There are 5,000 open computing jobs in the Beehive State that employers can’t fill because there aren’t enough skilled workers, Skonnard said. Yet, only 16 percent of Utah schools currently offer AP computer science classes.

Here’s how a few million dollars in the governor’s budget proposal this year might change that disparity and your child’s future.

The nitty gritty

There are a lot of open computer science jobs (most with a salary double the average Utahn’s), but not nearly enough people with the skills to fill them.

Seventy-one percent of new STEM jobs are in computing, but only eight percent of STEM graduates earned degrees in computer science, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the National Center for Education.

Skonnard believes the only way to close that gap is to get at the root of the problem: Early education.

Students who are exposed to computer science during their early years of education are much more likely to choose it as a major, Skonnard said. Women are 10 times more likely to get a degree in computer science if they take an AP class in the subject, and minorities are seven times more likely if they do the same.

Yet, while 65 percent of Utah schools offer students one or more computer science courses (eight percent higher than the national average), most of those courses are simply introductory, according to a recent multi-year study by Google and Gallup that assessed the status of computer science education across the U.S.

Only 66 percent of those courses include elements of computer programming and coding, and a mere 16 percent are intermediate or advanced courses that could propel students to college, the study shows. In fact, just 0.8 percent of AP exams taken by students were in computer science.

Utah also lags behind the nation when it comes to extracurriculars: only 59 percent of local schools have clubs or after-school activities that expose students to computer science, compared to the national average of 65.

“I believe that each student needs some exposure to coding very early on,” said Dillon Durrant, a first-year computer science teacher at Mountain View High School in Orem. “Not all kids will become programmers, but each student will then begin to see how technology around them works and will be able to pick apart how they can make the world a better place.”

Skonnard is forever grateful for a conversation about computer science he had with his son-in-law, who was then a freshman at Brigham Young University.

“He had no idea what computer science was even about, and, after just a few conversations with him, he realized he really identified with it and he wanted to explore it,” Skonnard said. “Now he’s like one of the top computer science students at BYU, but he would have … completely missed the on-ramp … if I hadn’t had an opportunity to talk to him.”

The past

Utah officials recognize there’s a gap. It’s not hard to miss.

“That gap is just going to continue to widen in the future as new jobs, new careers that we can’t even anticipate come online. It’s become more and more clear that we need to prepare our students better for that new world,” said Lt. Governor Spencer Cox.

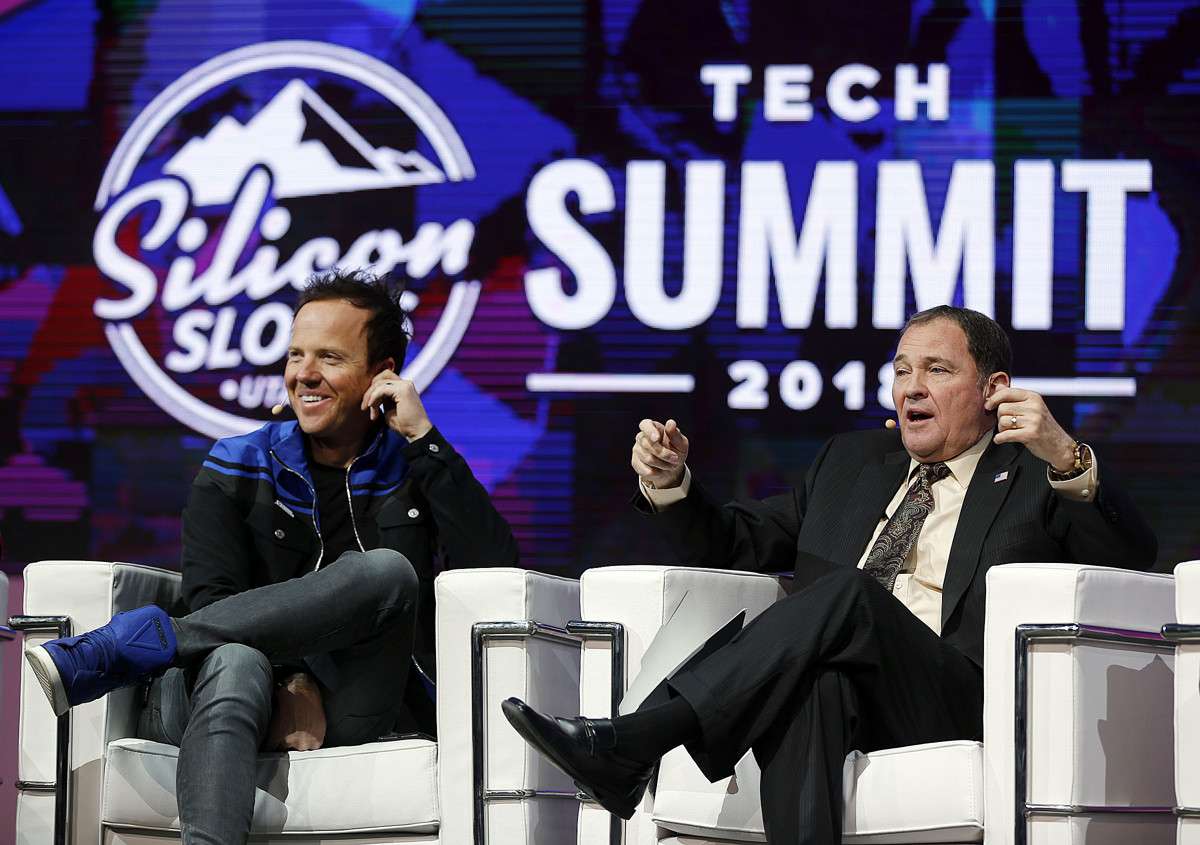

In 2016, a Senate bill appropriated funding for teachers to earn computer science endorsements and another created a grant program to develop K-12 computer science pathways. The year after that, companies from all over Utah signed a pledge during Silicon Slopes’ second annual summit to support universal computer science education for Utah’s students.

Skonnard, who is taking up the crusade on behalf of all Silicon Slopes, believes this year things will really start happening.

He’s encouraged, in part, by a detail of the governor’s budget proposal.

The plan

Each year, the governor creates a budget proposal that essentially tells the Legislature how he thinks they should spend the state’s money. This year, Gov. Gary Herbert appropriated $3.9 million to make three different computer science courses available in all Utah schools by 2022.

“This is a big deal that the governor said to the state in his proposed budget that we’re going to commit to going in and solving this problem,” Skonnard said.

The state also created a task force called Talent Ready Utah (consisting of Skonnard, Cox, the state board of education and others) whose job it is to formulate a strategy that will help the state meet its goal — including rural areas where tech isn’t as prevalent.

Once that strategy is in place, it’s the Legislature’s turn to officially appropriate funding for the strategy and codify the plan. Though the governor’s budget proposal is a suggestion, of sorts, it’s up to the Legislature to decide whether the state will actually spend that money on computer science education.

“We had initial discussions with legislators, and they, too, recognize how important this is,” Cox said. “Hopefully they’ll take the governor’s recommendation and put some (funding) in the budget this year with the idea of being able to increase that over the next three years so we can get teachers ready with the certificate they need to be able to teach these classes.”

The challenges

Cox believes there are two main challenges to the 2022 goal. The first is incentivizing, training and paying computer science teachers.

“These careers are in such high demand that it’s really tough to get people who know what they’re doing in these classrooms, so we’re going to have to be able to budget more money,” Cox said.

The state is partnering with Pluralsight, which has offered its educational content to the Utah State Board of Education to help train teachers and prepare them for the classroom. The next step is incentivizing those teachers to take that training, Skonnard said.

The second main challenge is coordinating with the board of education to ensure that students who do take computer science will receive science or math credit in school, just as if they’d taken a course in biology or chemistry.

Both Cox and Skonnard agree that the goal's a work-in-progress, but one they believe is imperative to Utah’s success.

“I just wish I could have the same conversation my dad had with me, and the same conversation I had with my son-in-law, with every K-12 student in Utah,” Skonnard said. “That’s what this is meant to produce, and if we accomplish that, I will be happy. I don’t care who gets the credit. I don’t care how it gets done as long as it gets done.”