1787 letter from cash-poor George Washington hailed as ‘great discovery’

The man later known as the Father of His Country tried to raise money after the Revolutionary War ended by unloading some of his vast land holdings.

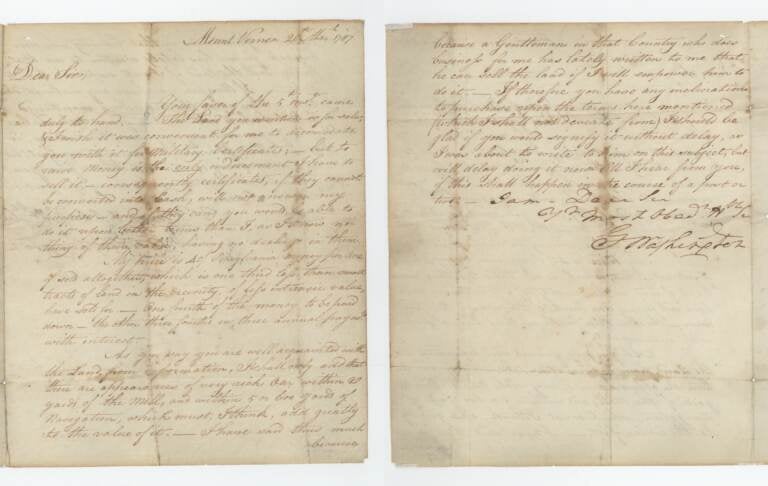

George Washington's full letter to Israel Shreve on March 5, 1787. (Courtesy of the Raab Collection)

George Washington led the war that saw the American colonies win their independence from Britain in 1783. Four years later the general was back at his Virginia plantation, trying to finish a long-neglected renovation project at Mount Vernon, determined to be a private citizen.

History shows the general was hesitant to attend the looming Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. Actually, Washington had other pressing concerns.

He needed cash, and in March 1787 decided to unload some of his vast land holdings.

Washington disclosed his intentions in a letter that, until recently, had been unknown to scholars.

He penned the two-page missive to Israel Shreve, a New Jersey man who had served under Washington as a colonel in the Continental Army a decade earlier at Valley Forge.

The topic of their exchange was 1,644 acres in western Pennsylvania. Shreve had expressed interest in the parcel, but wanted to buy it with credit in the form of military certificates.

No deal, Washington responded.

“I wish it was convenient for me to accommodate you with it for military certificates; but to raise money is the only inducement I have to sell it,’’ wrote Washington, who owned 70,000 acres across several states. “Consequently, certificates if they cannot be converted into cash, will not answer my purpose.”

Washington countered that for “40/Pennsylvania money per acre,’’ Shreve could get the land by putting one-fourth down and paying the rest “in three annual payments, with interest.”

For generations, the letter had been part of a small private collection in coal country in rural West Virginia, said Nathan Raab, president of the Raab Collection in Ardmore, Pennsylvania, which recently purchased it.

Raab says the letter to Shreve is worth $50,000, and is offering it for sale. Raab told WHYY News he has other letters by Washington but wanted to unveil “the newest and freshest” for Presidents Day.

The Raab Collection specializes in acquiring and selling documents of prominent historical figures, including Thomas Jefferson, Ulysses S. Grant, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ronald Reagan, and Winston Churchill.

Stumbling across ‘something really new and special’

The letter to Shreve, written nearly two years before Washington was elected America’s first president, “gives us a glimpse into the financial stresses and concerns of Washington, a man we think of in mythic terms but really had many of our own, very human issues,” Raab said.

“He had massive landholdings but I think what the reality here is he was cash poor. And although he had these assets, he was in a situation where he was helping family, entertaining people at his home, and he needed money. It shows him having the kinds of problems that anybody might have, which is, ‘I need cash. And your credit does me no good.’’’

Raab said most of Washington’s correspondence has been published and cataloged, but not the letter to Shreve. (The full text is at the bottom of this story.)

“Finding something that really sort of changes the historical record or adds to the historical record in a way that scholars and the public hadn’t previously known, that’s always exciting,’’ Raab said. “You feel like you’ve stumbled across something really new and special.”

Benjamin Huggins, associate editor of The Washington Papers project at the University of Virginia, called the letter’s surfacing “a great discovery with much historical interest.”

The letter “fills in a gap in the written conversation between the two men concerning the potential purchase of one of Washington’s land holdings in Pennsylvania, known as Washington’s Bottom,’’ Huggins told WHYY News.

“Up until the discovery of this letter, the only known correspondence in this 1787 exchange were three letters from Shreve to Washington. Now, thanks to this discovery, we have Washington’s reply.”

Huggins said his publication plans to add the letter to the “Newly Obtained and Previously Omitted Documents” section of its digital edition of Washington’s correspondence.

Washington was ‘in desperate need of cash’

Joseph Stoltz of the George Washington Presidential Library at Mount Vernon said he had been unaware of the letter to Shreve, but knew of Shreve’s previous letters to Washington about the possible purchase.

Mount Vernon’s agricultural business had declined while Washington was leading the war effort, he said, so the general found himself “in a serious cash hole’’ when he returned home.

“This is a guy that still has lots of wealth in terms of land, in terms of resources, especially this land out west that Israel seems interested in,’’ Stoltz explained. “And so he’s in desperate need of cash.”

One way was selling off some of his holdings, Stoltz said, but negotiations with Shreve stalled.

Meanwhile, Washington resisted pressure to attend the Constitutional Convention, where some 70 delegates were invited to decide how the former colonies would be governed.

“Honest to God, he thinks he is done with public life,’’ Stoltz said. “And it takes a lot for them to sort of drag him back out to get him to Philadelphia. That takes sort of a full court press of folks up and down the Eastern seaboard. And part of their argument [to Washington] is, ‘You’re really the only national figure with really high credibility ratings and really high favorability ratings.’”

Washington went, and was elected to preside over the convention, which lasted from May to September 1787, ending with the adoption of the U.S. Constitution.

The document was ratified, and the next year Washington was elected the first president of the United States. He served two terms, leaving office in 1796.

During his presidency, a deal on the land was finally forged, according to Rabb.

As the story goes, Shreve approached Washington nearly midway through his second term, in June 1794, to inquire again about the same parcel.

And in January of the following year, Washington sold him the entire 1,644 acres.

Shreve paid in cash.

Stoltz added a historical footnote to the tale. Both Washington and Shreve died on the same day: Dec. 14, 1799.

Washington’s letter to Shreve, Mount Vernon, March 20, 1787

(As provided by the Raab Collection)

“Your favor of the 5th inst. came duly to hand. The land you mention is for sale, & I wish it was convenient for me to accommodate you with it for military certificates; but to raise money is the only inducement I have to sell it. Consequently, certificates if they cannot be converted into cash, will not answer my purpose. And if they can you would be able to do it on better terms than I, as I know nothing of their value, having no dealings in them.

“My price is 40/ Pennsylvania money per acre if sold altogether, which is one third less than small tracts of land in the vicinity, of less intrinsic value, have sold for. One fourth of the money to be paid down – the other three fourths in three annual payments, with interest.

“As you say you are well acquainted with the land from information, I should only add that there are appearances of very rich oar [copper ore] within 20 yards of the mill, and within 5 or 600 yards of navigation, which must, I think, add greatly to the value of it. I have says thus much because a gentleman in that country who does business for me has lately written to me that he can sell the land if I will empower him to do it.

“If therefore you have any inclination to purchase upon the terms here mentioned (which I shall not deviate from), I should be glad if you would signify it without delay, as I was about to write to him on this subject, but will delay doing it now till I hear from you, if this shall happen in the course of a post or two.”

[signed] G. Washington

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.