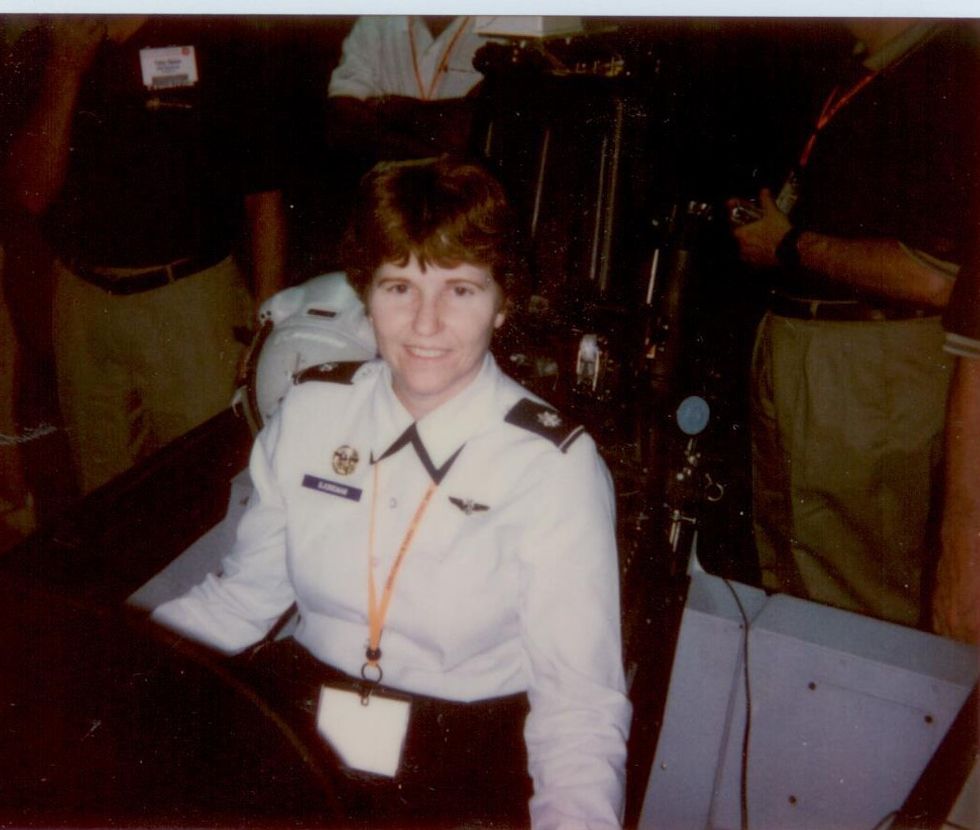

Eileen Bjorkman joined the U.S. Air Force in 1980, rising to the rank of Colonel before her retirement in 2009. She flew more than 700 hours as a flight-test engineer in more than 25 different aircraft, primarily the F-4 Phantom II, F-16 Fighting Falcon, C-130 Hercules, and C-141 Starlifter. She holds Bachelor’s degrees in computer science and aeronautical engineering, a Master’s degree in aeronautical engineering, and a Ph.D. in systems engineering. Bjorkman is currently the executive director of the Air Force Test Center at Edwards Air Force Base, California.

The following conversation has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

Popular Mechanics: You attended the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School (TPS) from 1985–1986. Can you talk a little about what test-pilot school teaches, and how it set you up for your career in the Air Force flight-test program?

Eileen Bjorkman: First, let me clarify that I was a flight-test engineer, not a test pilot. TPS trains not just pilots, but also combat-system operators and flight-test engineers. The combat-system operators and flight-test engineers have pretty much the same curriculum as the pilots, but we fly in the back seat or back end of an airplane or monitor a test from a control room on the ground.

TPS teaches a broad brush of all sorts of testing, from how to evaluate the performance and flying qualities of an aircraft to how to evaluate the systems onboard an aircraft, such as avionics, radars, and weapons. You learn the theory about how an airplane flies and how those systems work and how to test them, and then you go out in an airplane like an F-16 or a C-12 and collect some real-world data, analyze that data, and write a report on it. And you don’t just do that once, you do it for each type of test, and you fly in many different kinds of airplanes so you see how an aircraft’s design impacts how it performs and how you approach the testing of that design.

The thing about TPS that sets you up for your career is that you get exposure to almost everything that happens in testing and all the different kinds of systems that you might be testing, which gives you a huge advantage. For example, I never had any direct experience with testing munitions, but when I had a job that required me to do some work with munitions, the exposure I had at TPS helped me get quickly up to speed.

In the 1970s and 1980s, you flew aboard 25 types of military aircraft as a flight-test engineer. Did the Cold War and the need to get capable planes in service add any sense of urgency to the job?

Yes, definitely. We always strove to stay one step ahead of the Soviet Union. I loved testing because we either showed that something was ready to move into an operational system to help us stay ahead, or we found problems that needed to be fixed before the system was fielded, so the operators didn’t have to find those problems.

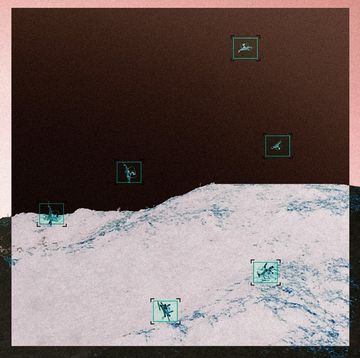

As a flight-test engineer, you helped develop combat systems, such as the LANTIRN navigation and targeting pod. LANTIRN was a major success in the 1991 Gulf War, allowing U.S. forces to pick off Iraqi targets on the ground with ease, even at night. What was it like getting a preview of high-tech gear before it hit the squadrons?

It was always a lot of fun to see the new systems, but it was also very sobering to realize how hard it is to get some of the new technology right. Although some systems worked great when we got them, other times the manufacturers had to make many changes before the system started working right. No matter how much lab and ground testing you do, there’s almost always something that goes wrong once the system gets in the air for the first time. That can be frustrating, but it’s also very rewarding when the problems get fixed and you see the system working right. And then seeing it operated for the purpose it was intended for is really rewarding.

What were some of your most memorable experiences as a flight-test engineer?

I’d have to say my most memorable experience wasn’t in an airplane at all, but was monitoring a strip chart in the control room at Edwards Air Force Base during the first flight of the C-17 in 1991. I didn’t really appreciate at the time what a big deal it was to be involved in the first flight of a brand-new airplane. But it is the one memory that has really stuck with me. And it was really rewarding watching the C-17 flying people out of Afghanistan in August 2021. I was so happy to have been a part of that program and see that airplane become such a huge success.

You commanded two squadrons, the 746th and 846th Test Squadrons. What did squadron command teach you about people and how to lead them?

I think the biggest thing is you have to be yourself, but also push yourself outside your comfort zone. At my first squadron, from day one, I led with a very collaborative style of leadership, which is my natural style. But my second squadron had some major issues when I took over, and I had to be a much more direct leader than I was comfortable with to address the immediate problems they had. I even had to be a bit of a jerk at times. But even while I was doing that, I established a collaborative process with the rest of the squadron leadership about what the squadron needed to do in the future. About six months after I took over, the squadron had turned a corner, and I was able to stop being so direct and brought my collaborative leadership to the daily operations as well. But having to lead outside my normal leadership style for a while was probably one of the hardest things I had to do in my Air Force career.

Women are now flying all types of U.S. Air Force combat jets, including the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber. What are some modern-day struggles for female jet and bomber pilots?

There are still some issues that my generation dealt with—like chauvinistic attitudes, poor-fitting equipment and relief on long-distance flights—but from what I read, the main issue is the same as civilians: how to blend a career with having a family. The military has made some great strides in this area, such as allowing women to fly longer while they are pregnant and providing more maternity (and paternity) leave. But there is still much work to be done.

You’re also a historian, with your book, Fly Girls Revolt: The Story of the Women Who Kicked Open the Door to Fly in Combat, coming out this May. What was the turning point that led to lifting the ban on women in combat roles?

The turning point was the Persian Gulf War in 1991, which opened the public’s eyes to the reality that women were essentially already in combat. But that turning point would not have been possible had it not been for the women who had been fighting for equality in the military since World War II, and my book covers all of that history.

You were assigned to the Pentagon on 9/11 as the associate director, Transformation Initiatives, at the Defense Modeling and Simulation Office. Were you there that day? If so, what was it like?

I was not there. But I do have a story about that day. Although I spent a lot of time at the Pentagon, I was in one of the offices that had been moved out for the renovation. I was in the Pentagon the Friday before, and I had walked around the new area (where the plane later hit) and marveled at the renovation. I had an office in the wedge in 1993–1995, so I was really impressed with the difference between that time and 2001.

I flew out of National Airport the evening of September 10 to attend a conference in Orlando. I had just finished giving a presentation when someone announced the terrorist attacks. The conference, of course, got put on hold. All the cell phone towers were saturated, so I finally went back to my hotel room and managed to get a local dial-up line to my AOL account. One of my sisters had sent me an email that she had managed to contact my office and they said I was in Florida, and I had an email from one of my Test Pilot School classmates in Japan who wanted to know if I was okay.

All of the attacks were horrible, but it was particularly awful to watch the Pentagon burn, especially having just been in that section three days earlier. I was frantic to get back, but of course, all the return flights were canceled. I wound up keeping my rental car and driving back with a couple of other people. On my way back to the airport on Friday to drop off my rental car, I drove by the Pentagon and it was still smoldering. It was all so surreal, the whole world changing in an instant like that.

Which plane in your 700 military flight hours was your favorite to fly and why? If you could fly any modern plane, which would it be and why?

The F-4 for sure; it was just a fun plane to fly, and it was the workhorse of the Vietnam War. If I could fly any modern plane, it would have to be the F-22, although there isn’t a back seat, so that won’t happen! I did a lot of analysis on that airplane in the early 1990s, and I just fell in love with it. It’s not just a better F-15; it’s a whole new class of airplane.

What message do you have for young girls and women that are thinking about a military aviation career?

Don’t ever let anyone discourage you! You have as much right to be in military aviation as anyone else. To have a strong military and a strong country, we have to use the talents of every single person in the United States. Women make up 50 percent of the talent in the U.S., and you are part of that 50 percent. We need you!

This story is part of an ongoing series for Women’s History Month. Stay tuned for future stories each week in March.

Kyle Mizokami is a writer on defense and security issues and has been at Popular Mechanics since 2015. If it involves explosions or projectiles, he's generally in favor of it. Kyle’s articles have appeared at The Daily Beast, U.S. Naval Institute News, The Diplomat, Foreign Policy, Combat Aircraft Monthly, VICE News, and others. He lives in San Francisco.